The idea of hiding under the water to strike at a superior enemy is not a new one. Inventors over the centuries have sketched craft that would allow them to approach in secret, then do violence to their opponents. Problems of propulsion, of endurance, and of weaponry thwarted them, and the first serious attempt wasn't made until 1776, when an American named David Bushnell devised the Turtle, a wooden submersible that would be piloted by a single man underneath a British warship, attach an explosive charge, and then run away. When a volunteer, Sgt. Ezra Lee of the Continental Army, attempted to do just that to HMS Eagle on September 6th, he was unable to attach the charge and had to abandon the effort. Turtle was later destroyed to keep her from falling into British hands.

A model of Turtle at the Submarine Force Museum, Groton, CT1

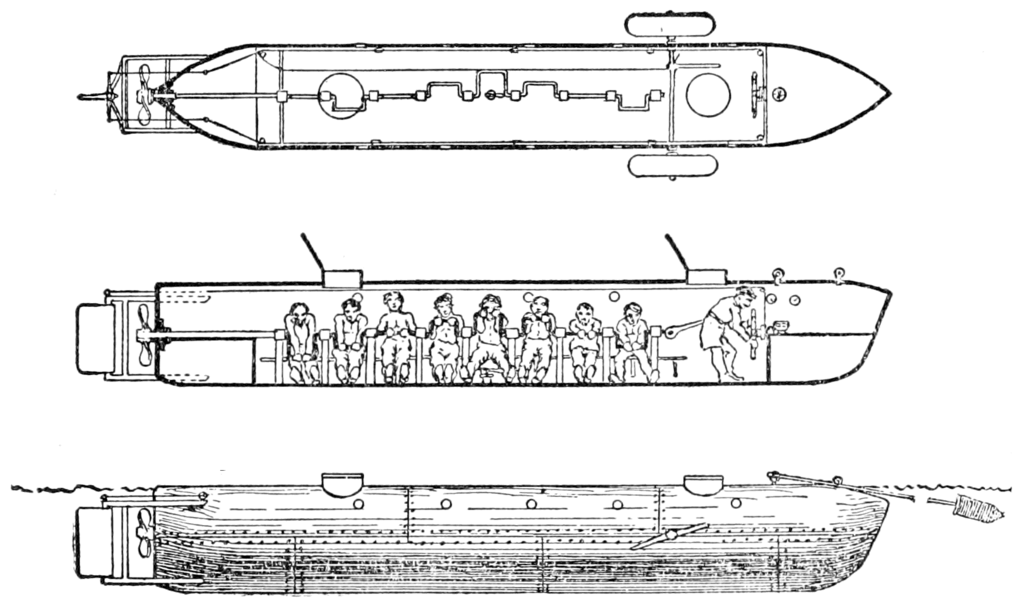

It took another 88 years for a submarine to actually manage to sink an enemy ship. The pressure of the Union blockade during the American Civil War forced the Confederacy to search for asymmetric advantages, and an inventor named Horace Hunley built a submarine that could carry a spar torpedo, a charge on the end of a long boom. A crew of eight drove the propeller through a crank. The submarine, named after Hunley, was not a spectacular success, sinking twice in testing and killing 13 men in the process, including her inventor. Despite these setbacks, the Confederates persevered, and on February 17, 1864, Hunley managed to attack the sloop Housatonic, sinking her and killing five Union sailors. However, the victory proved Pyrrhic, as Hunley was sunk by the same blast.2

H.L. Hunley

The last quarter of the 19th century saw a number of innovations that made the submarine practical for the first time. Chief among these were the lead-acid storage battery, the internal combustion engine, and the self-propelled torpedo. But even then, there were serious issues. The obvious way to operate a submarine was to let water into special tanks, which quickly became known as ballast tanks. There were serious problems, however. To make the submarine neutrally buoyant, so it would stay at a given depth, the tanks generally had to be kept only partially full, leading to free surface effects that tended to force the bow or stern down. Irish-American engineer John Holland found a solution to this. Instead of trying to make the submarine neutrally buoyant, he fitted it with diving planes, fins that could be rotated to produce lift, much like an airplane's wing. Filling the tanks all the way removed the free surface problem, and any remaining buoyancy was cancelled out using the diving planes and small compensating tanks. The result was the first truly practical submarine. Holland initially worked for the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish revolutionary group, and the submarine he built for them, the Fenian Ram, is still in existence. After a financial dispute, they parted ways, and Holland's next vessel was bought by the US Navy in 1900 and given his name. The next year, the RN also licensed his design, and named the resulting class the Hollands.

HMS Holland 13

The earliest submarines were entirely focused on underwater operations and intended primarily for coastal defense purposes. However, exercises quickly showed that such boats4 had to operate on the surface fairly frequently, but were not particularly effective there. Conning towers were installed, at first to stop the submarines from swamping when waves broke over them, and later to give better views while on the surface. Increased interest was also shown in long-range boats, capable not only of defending ports but also of taking the war to the enemy. This required better surfaced performance, as high-speed underwater running quickly drained the batteries. A boat's maximum underwater speed would run the batteries flat in an hour, and even at the relatively slow speed of 5 kts it was unusual to find one that could exceed 100 nm before she had to surface to charge batteries. As a result, submarines quickly began to develop more boat-like hulls for high surface speed, although the basic concepts of submarine warfare, most notably the need for submarines to attack submerged, weren't really questioned until WWI. Despite these limitations, many thinkers, most prominently Jackie Fisher, believed that the submarine would render the battleship obsolete in short order.

German U-boats, 1914

WWI changed everything for the submarine. For the most part, and despite a few notable exceptions, warships at sea proved much harder for submarines to sink than expected. Once a submarine was submerged, it was usually too slow to reach firing position against a fast-moving warship. On the other hand, navies had almost no idea how to hunt submarines, and took several years to develop the necessary techniques. However, merchant ships were mostly too slow to evade submarines. At the outbreak of war, most believed that the traditional prize rules would prevent submarines from waging an effective campaign against merchant ships, as they required the crew to be placed "in a place of safety" somewhere more secure than the ship's boats. Instead, the Germans soon decided to operate their submarines without any of the customary restrictions of international law, a choice that nearly brought Britain to its knees and drew the United States into the war. Submarines on the surface turned out to be extremely hard to see, particularly at night, and submariners quickly seized on the opportunity this presented to use their vessels as torpedo boats when the visibility was bad. Deck guns were also fitted to be used for killing small ships, as torpedoes were large and expensive, and most submarines could carry no more than two dozen of them. Eventually, the British managed to fight back, but such was the horror of the submarine campaign that Germany was totally banned from owning such vessels under the Treaty of Versailles.

U-995, a Type VII U-boat

The interwar years for the submarine were ones of refinement. Designs and components were improved, but the basic concept remained a submersible torpedo boat, moderately fast on the surface and slow below it. The biggest variable was size, as different nations built bigger or smaller submarines, depending on whether they expected to fight in coastal waters or the broad reaches of the open ocean. At one extreme were the Germans, who built 703 Type VII U-boats of 770 tons, most of which operated in the North Atlantic and the waters around Europe. The standard American submarines, beginning with the Gato class, were twice the size of the Type VII, giving much better range and habitability for long patrols in the Pacific. Both of these types were used in vigorous campaigns aimed at strangling the war economies of Britain and Japan respectively. The U-boats came close, but were ultimately defeated by the anti-submarine warriors of the Allies, while the Japanese were unable to come to grips with their assailants, and were slowly strangled.

USS Batfish, a standard American submarine of WWII.5

WWII marked the beginning of two decades of radical change for the submarine. Surface attacks were thwarted by the invention of radar, and underwater performance became ever more important. The Germans had already begun thinking in that direction, attempting to get around the limitations of batteries by using high-purity hydrogen peroxide. In theory, it offered an energy source much more potent than electricity that didn't require oxygen, but the best commentary on the substance came from the nickname of one of the RN's peroxide boats, which was known as HMS Exploder. However, the basic design prepared for the German peroxide submarine was re-purposed into the Type XXI, which had three times the battery capacity of the Type VII and larger motors, making it capable of 17 kts submerged, over twice the underwater speed of the earlier U-boat. This revolutionary speed allowed the Type XXI to evade most ASW weapons of the day, although only one boat made a combat patrol before the end of the war, and she failed to sink anything.

Type XXI U-boat

A large number of Type XXIs fell into Allied hands when Germany surrendered, and quickly became the inspiration for the postwar generation of submarines. These vessels, either newly-built or converted from wartime boats, were streamlined and equipped with bigger batteries and more powerful motors, as well as another late-war innovation, the snorkel. This allowed them to run their engines while submerged, greatly reducing their risk of being spotted by radar. To gain even greater underwater performance, the US, Britain, and the Soviets all experimented with peroxide too, but ultimately abandoned the substance in favor of another technology that offered nigh-infinite underwater endurance.

Nautilus underway on nuclear power.

This was the nuclear reactor, which was not only independent of air, but also of fuel. Work on submarine reactors began in the immediate aftermath of the war, under the supervision of Hyman G. Rickover,6 and the first nuclear submarine, Nautilus, was "Underway On Nuclear Power" on January 17th, 1955. Within a matter of months, it was obvious that she was something revolutionary. She was capable of maintaining 23 kts indefinitely, thwarting previous ASW tactics which had largely been based around the limited endurance and speed of the submarine, holding them down until they were forced to surface. New methods had to be worked out, while nuclear submarines made several high-profile demonstrations of their capabilities. In 1958, Nautilus became the first ship to reach the North Pole, transiting from the Pacific to the Atlantic entirely under the ice. Two years later, Triton circled the globe entirely submerged in 60 days and 21 hours.

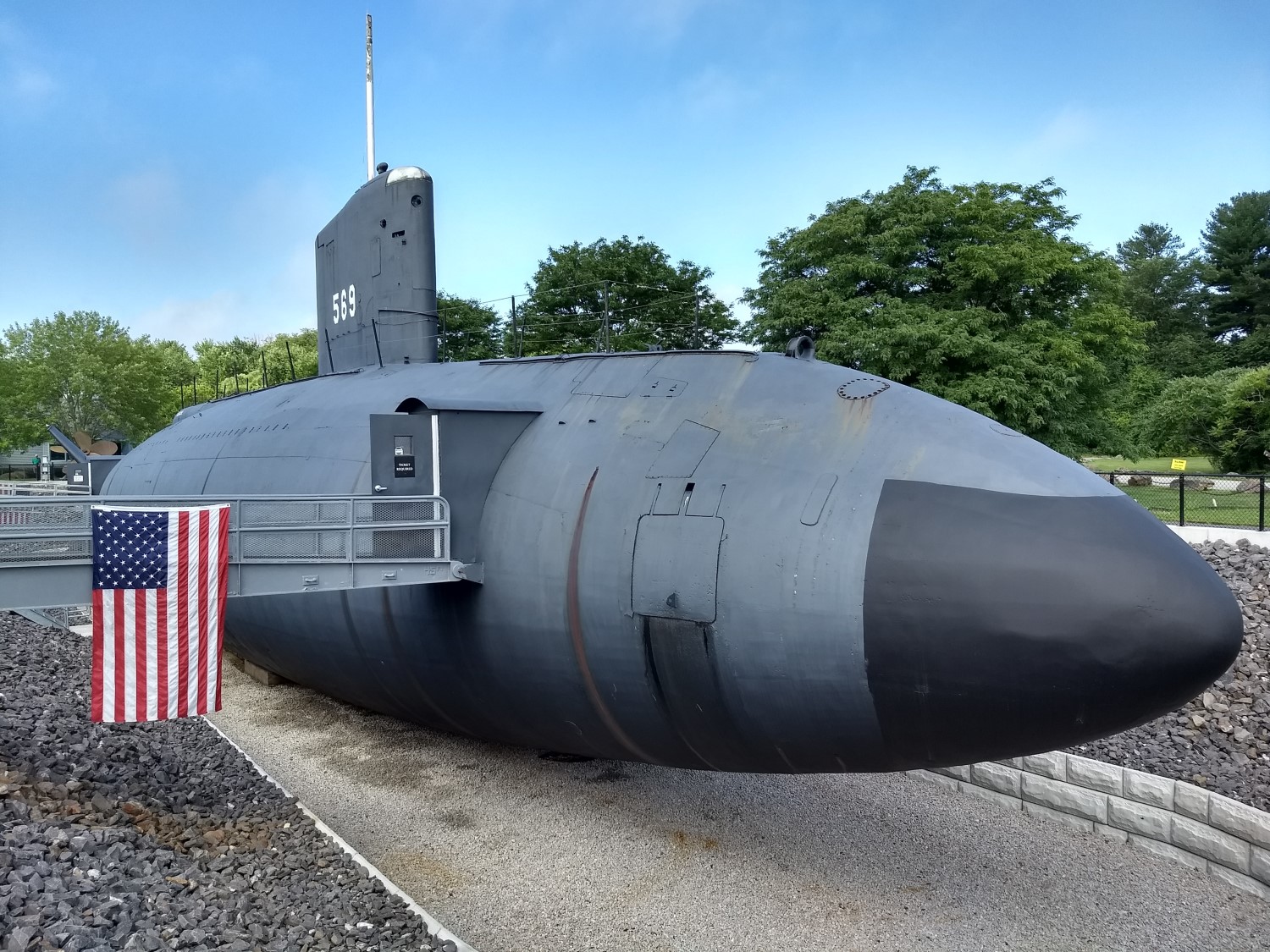

USS Albacore7

But one more step was needed to make the nuclear submarine truly at home underwater. The first nuclear boats had traditional submarine hulls which worked well on the surface, but were slow and not particularly maneuverable underwater. Hydrodynamic research revealed that the ideal shape was a teardrop, often known as an Albacore hull after the experimental submarine that first took it to sea. Submarines could now maneuver in 3 dimensions, behaving more like airplanes than like boats. The true submarine had arrived at last, and looked destined to fulfill the prophecies of men like Jackie Fisher.8

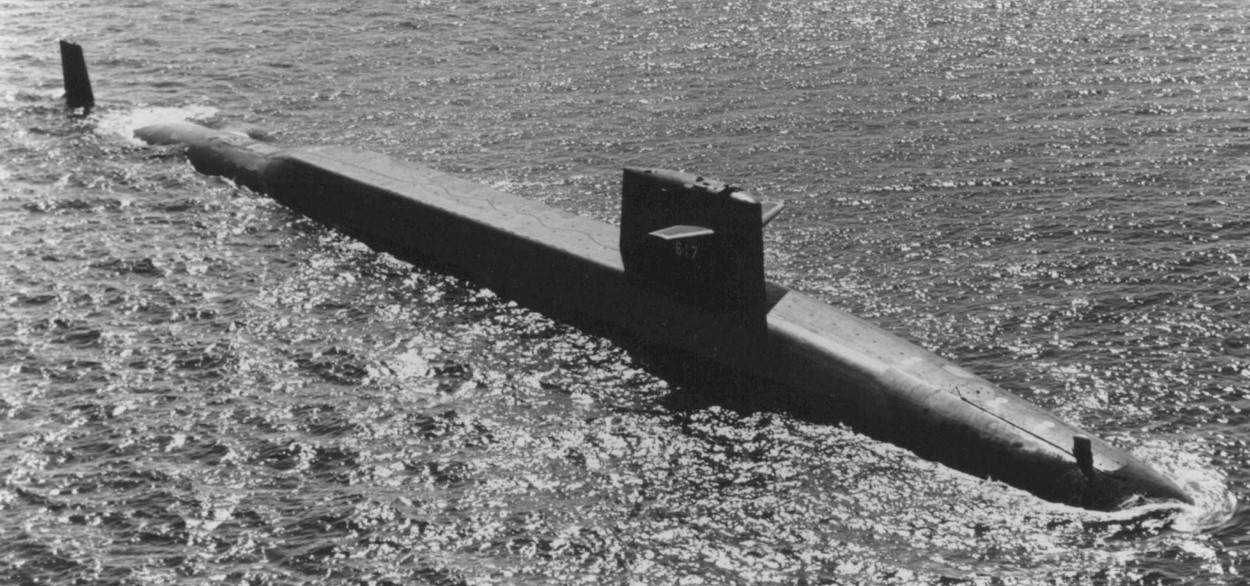

Ballistic missile submarine Alexander Hamilton

But more was to come from the nuclear submarine. The 1950s also saw the development of guided missiles, and enterprising submariners saw the chance to give their boats a new mission, attacking targets on land, as well as at sea.9 The first attempts at this used cruise missiles, launched while the submarine was on the surface, but these were soon superseded by ballistic missiles, and the "boomers", as they are known, have been an important deterrent to nuclear war from the 1960s to today. The cruise missile was never entirely discarded either, although for a long time it was relegated to specialized anti-shipping submarines. However, the development of the Tomahawk missile in the 1980s gave a new land-attack role to standard attack submarines, which can now strike targets hundreds of miles inland without warning.

HMS Valiant, the first submarine with raft machinery.

The one real drawback of nuclear submarines was that they were fairly noisy. The reactor required pumps that had to be run at all times, while a diesel boat that wanted to hide could shut down virtually everything.10 This was a particular problem in the late 50s as sonar improved to the point that it became feasible to track nuclear boats over some distance. The result was that performance quickly took a back seat to silencing, and submarines grew to accommodate all sorts of features that prevented noise from being transmitted to the sea. The most prominent of these are special spring-mounted rafts that isolate the main machinery, although nearly every feature of a modern submarine is designed to minimize signatures. An Ohio class missile submarine is said to be quieter than the surrounding ocean. This stealth has given the nuclear submarine another job, lurking off hostile coasts and gathering information, particularly on enemy electronic systems.

German Type 212 Submarines

Diesel submarines haven't stood still over the past half-century either. They have benefited from the innovations in hydrodynamics, combat systems and weapons made for their nuclear brethren, although the limitations of their propulsion systems have become, if anything, increasingly important. A modern diesel boat is incredibly quiet and deadly, but it is ultimately more like a mobile minefield than a true deep-water warship. However, it costs only a fraction as much, so many more countries can operate them. Some have attempted to bridge the gap with air-independent propulsion, a system that provides more power than is possible on batteries without using atmospheric oxygen.

Virginia class submarine Missouri passes her battleship namesake

Submarines have been an important element of sea power for the past century and more. From the German attempts to strangle Britain in the world wars, to the successful American blockade of Japan to the Cold War, when ballistic missile submarines patrolled to provide leaders with a second-strike capability. Today, more than ever, the stealth and firepower that submarines bring to battle, and to operations short of war, are vital.

1 My photo. ⇑

2 She was raised in 2000, and is now on display in Charleston, South Carolina. ⇑

3 Holland 1 has been preserved, but I don't have a good picture for some reason. ⇑

4 Submarines even today are universally referred to as "boats" instead of "ships", as the early ones were small enough to be considered boats instead of ships and the tradition stuck. ⇑

5 My photo. ⇑

6 Rickover would go on to be in charge of the Navy's nuclear reactor program until he was forced to retire in 1982. He spent 63 years on active duty, by far the longest career of anyone in the history of the US military. He was also a rather difficult man, famous for, among other things, the "radiator test", where he would hit samples of equipment against his radiator until they broke. ⇑

7 My photo. ⇑

8 It's worth pointing out that both Nautilus and Albacore are preserved as museum ships, and very good ones at that. ⇑

9 One pioneer of this was Eugene Fluckey, who used his boat, the Barb, against Japanese shore targets during the closing months of WWII, even sending a team ashore to blow up a train. His book, Thunder Below, is excellent, and you should get a copy immediately. ⇑

10 Of course, said diesel boat has to charge batteries occasionally, while a nuke boat doesn't. ⇑

Comments

...Just a little clarification on the loss of the Hunley - she actually survived her attack on the Housatonic by between 45 minutes and an hour. Her seams were almost certainly sprung to some extent, but it's not clear how badly. Her skipper let her drift with the ebb tide, and at about 930PM surfaced just long enough for them to show a signal lantern - seen both ashore at Fort Moultrie and by Housatonic's survivors. What likely happened after that is that she dove one more time to get past the thoroughly angry United States Navy, and with far more water in the tanks than she should have had and a crew likely suffering from anoxia and hypothermia, she was steered under control into the seabed. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

I actually looked into this while writing. The initial story after Hunley’s rediscovery was that she survived for a while, thanks in part to misconduct on the part of Clive Cussler’s team, who reported that she was over a mile from Housatonic. They eventually admitted that she was in fact 100 yards from her victim, and recent evidence all points to the crew being killed very shortly after the attack. I don't have a good explanation for the signal lantern, beyond battle doing weird things to people.

I second the recommendation to read Thunder Below. It is quite a story.

@bean - Do I recall correctly that USS Batfish is more or less local for you? And if so, do you have any information about her current status post-Arkansas River flood beyond what I gleaned from a simple Google search (to wit, she's out of position and settling into mud with several degrees of list)?

She’s ~2 hours away, and I don’t have any particular information beyond what you do. I just hope that it stops raining on us, because I’m having to mow the yard way too often. But I wish them the best of luck.