Proposals for using the airplane to deploy torpedoes predate the outbreak of WWI, with the earliest prominent speculations coming from American Admiral Bradley Fiske, who took out a patent on the idea in 1912. The first actual drop took place in June 1914, although the anemic airplanes of the day meant that early tests were done with obsolete (and light) 14" torpedoes.

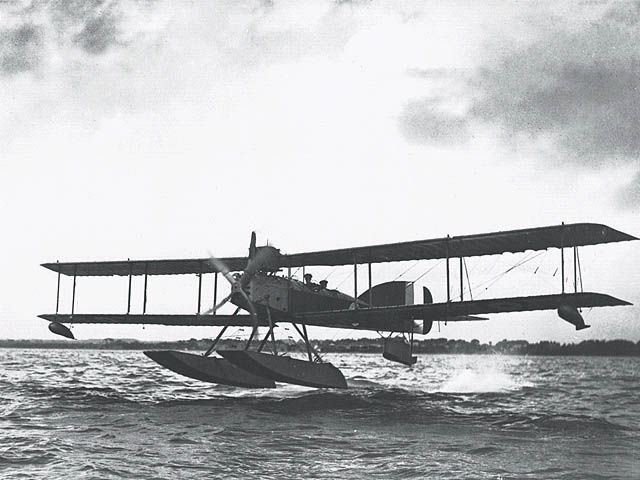

A Short 184, the first plane to conduct a successful aerial torpedo attack

The British were the first to use the aerial torpedo in action, deploying torpedo-carrying seaplanes to the Dardanelles during the Gallipoli campaign. The first successful torpedo attack was made on August 12th, 1915, although the target ship was already abandoned and aground. Five days later, a second attack managed to hit a ship underway, although the Turks successfully salvaged her. A second plane that had not launched its torpedo was forced down by engine problems, and after the pilot found that he couldn't get back into the air with his torpedo, he decided to taxi around until he could find a suitable target. He eventually located a Turkish tug and managed to sink it with his torpedo before taking off for home.

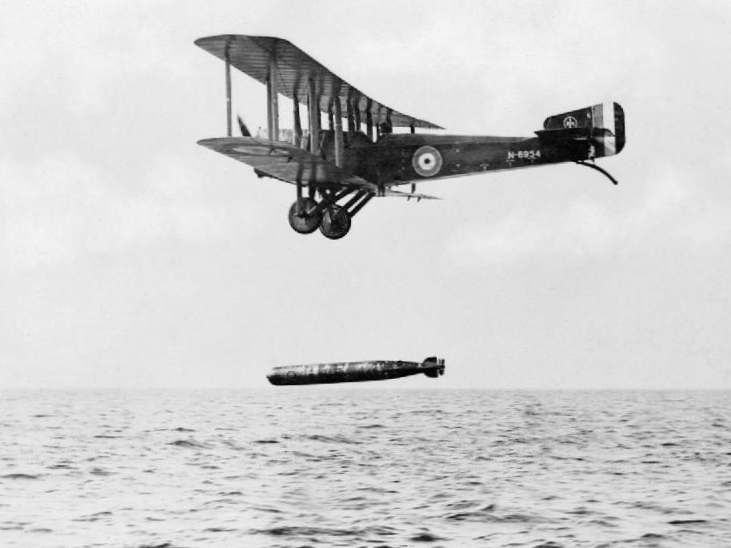

A Sopwith Cuckoo

Development on torpedo bombers continued throughout the war, with the British taking the lead, although it appears that there were no further operational uses. By the time the Armistice was signed, they had drawn up plans for a carrier attack on the High Seas Fleet using Sopwith Cuckoos launched from a group of carriers in the North Sea. This attack, which was the conceptual forerunner of Taranto and Pearl Harbor, was intended to put the High Seas Fleet out of action, allowing the British far greater freedom to operate against the U-boat bases that were threatening their convoys. Throughout this period, the basic tactic was fairly simple. The torpedo was simply slung under the plane, then activated and dropped clear while the plane was heading towards the target. This was perfectly adequate during WWI, when planes were slow and likely to be flying very low, but as aircraft speeds increased and pilots tried to drop from higher altitudes, problems began to appear.

A Mk 13 torpedo porpoises after being dropped

The first and biggest problem was getting the torpedo safely off the plane and into the water, which started with making sure that the torpedo hit at the right angle. If it was too steep, it might go too deep, which could see it bury itself in a shallow bottom or pass under the target before it returned to the appropriate depth, or it could just break up entirely. To help it get back to depth quickly, the elevator was usually set with an up angle, although this caused issues if the torpedo rolled on entry, as they would turn the torpedo, producing a "hook".1 Beyond that, as torpedoes were dropped higher and faster, damage to the torpedoes became an increasing problem. Dealing with this meant not only limiting speed and altitude (100 kts and 50' were standard around 1930) but also elaborate mechanisms, like a British design that dealt with the problem of roll by securing the torpedo with wires and essentially dropping it out of the aircraft's slipstream before it was allowed to fall freely. This was awkward, as it limited the bomber's ability to maneuver until the wires released, and that tended to be unpopular with crews that were being asked to fly low and slow into the teeth of a target's defenses.

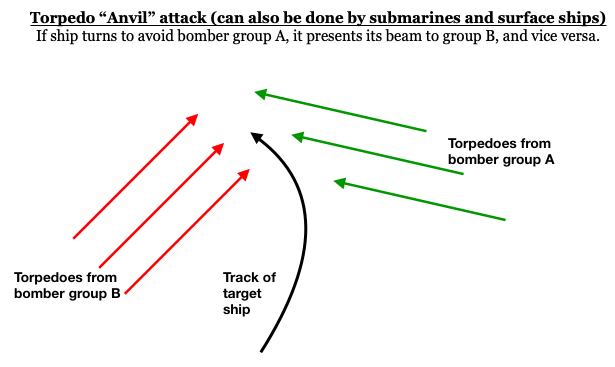

Also fairly slow was the torpedo itself, often not much faster than the target ship. A typical example was capable of about 40 kts and had a range of 1,500-2,500 yards. Firstly, this meant that the pilot would need to compensate for the speed of the target ship using a device known as a torpedo director. Even more importantly, a single torpedo would be fairly easy to dodge, the usual tactic being to turn towards the direction of attack to minimize the exposed width of the ship, a procedure known as "combing". The counter to this was to attack en masse, with the preferred method being to attack in two lines about 45° on either side of the bow, known as the "hammerhead" or "anvil". This would leave the target ship with no real way to avoid exposing its side to one attack if it tried to comb the other. If executed correctly, this was very effective, although aerial torpedoes were limited in size and warhead weight2 which meant that it typically took more than one hit to sink a ship. Per Striking Power of Airborne Weapons, a single torpedo was unlikely to sink even a destroyer, although two would likely put down anything smaller than a treaty cruiser. Three would probably be required for a carrier, while 4 or more might be needed for a battleship.3

A TBD Devastator, showing the angle on the torpedo

Despite this, the torpedo was generally the most accurate weapon available (as it could only miss in one dimension instead of two) and it delivered its payload to the most effective spot. This was enough to keep it around despite the fact that it was complex and costly, and typically weighed around 2,000 lb. Until the mid-30s, carrying this kind of payload imposed serious penalties on the performance of single-engine airplanes, such as those flying from carriers. The USN contemplated getting rid of the torpedo bomber entirely in favor of reliance on dive and level bombers, going so far as to delete torpedo storage from Ranger in 1931. As engines grew more powerful, this problem went away, and the USN reembraced the torpedo with the procurement of the high-performance TBD Devastator in 1934.4 Unfortunately, the TBD's performance was limited by the decision to mount the torpedo at an angle to the fuselage for easier loading, because it was parallel to the deck when the plane was parked. This meant that the Devastator had to adopt a rather extreme nose-up angle during the attack run, slowing it down significantly, a problem that would be resolved by the follow-on TBF Avenger.

But more was to come for the torpedo in the late 30s, as navies worked to increase drop speeds and altitudes. We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 I think the torpedo generally would straighten out after the hook, but the process would move it some distance to the side. It's also possible that some hooks just sent it off on the wrong course, but my sources aren't quite clear on this. ⇑

2 Typical numbers were 400 lbs at the start of the war and 600 lb at the end. Surface-ship and submarine torpedoes typically had 600-800 lb warheads. ⇑

3 This obviously depends on the battleship, and Yamato and Musashi famously required 13 and 19 torpedoes respectively. ⇑

4 No, this is not a joke. For the mid-30s, the Devastator was indeed very good. The problem was that it was obsolescent by 1942, something the USN had already recognized and taken steps to fix. ⇑

Comments

...Interestingly, RANGER actually did get an actual torpedo squadron - VT-4, the only VT commissioned at sea (just after Pearl Harbor) and which stayed with her until 1945. And she also had TBDs assigned before that with Scouting 4; they stayed aboard until the TBD's withdrawal from service in '42.

I actually ran across a reference to VT-4 while looking into something else for the next post, but didn't want to clutter the narrative with details about that.

Based on the tables in the linked doc, it looks like there's a sort of "hit point" effect, where the probability of a kill jumps up suddenly from a fairly low percentage to 90+% at a certain number of torpedo hits, which is contrary to my intuition that for small torpedoes, ships would mostly be killed by a "critical hit" effect where each torpedo has a certain chance of hitting just right and dealing a killing blow, especially since the number of hits seems to scale nonlinearly with the size of the ship (e.g. I'd expect a 30,000T battleship to have a lot more than 2-3x the "hit points" of a 2,000T destroyer).

@Erica Rall

I think damage control getting saturated (men, machinery, attention, &c) and being unable to keep up is the likly cause of the threashold effect.

My best guess is that it's a compartment thing. Ships were typically designed to stay afloat with a certain number of compartments flooded, and the general assumption was that a torpedo would flood all the compartments within a certain length. So a destroyer would probably stay afloat with the compartments a single torpedo could flood, but any more damage and she was likely to go down. A bigger ship would take more hits, and might have TDS that would keep anything from flooding on the first hit or two.

Of course, if the torpedo hit, say, the rudders of a battleship, you might get a very much larger effect (total mobility kill!) than if, say, the torpedo hit midships on the armor belt (yawn, a small dent).

Musashi had a bunch of torpedo hits, but they were on both sides, so it took a lot of them to sink her. Next year, Yamato's attackers were ordered to try to get all their torpedo hits on one side, and she capsized quite a bit earlier in the process.

Related: Yamato was already dead in the water and in the process of being abandoned when the last wave of torpedo bombers came in, so at least the last 4 or so hits were definitely superfluous to her sinking (though that probably was not entirely obvious to the attacking aircrews). Of course even needing "just" 6-8 torpedo hits to sink them still marks the Yamato & Musashi as pretty damn tough.