Amphibious warfare is the oldest form of naval warfare, dating back to the day when a tribe first crossed a lake to take their enemy by surprise. Since then, the art of moving soldiers across bodies of water into enemy territory has been practiced in a staggering number of variations worldwide. In the late Bronze Age, the Sea Peoples practiced amphibious warfare in the eastern Mediterranean, invading and toppling several civilizations.

Ships beached at Marathon

The first well-attested amphibious operation is the Persian landing at Marathon in 490 BC. Darius of Persia wanted to bring Athens under his control as a base for conquering all of Greece, and dispatched a force across the Aegean to do so. The Athenians managed to prevent the Persians from moving inland from the plain of Marathon, then attacked them five days after they landed, ultimately throwing them back into the sea despite being badly outnumbered.1 It's possible that an attempt to reembark part of the army and attack Athens directly was involved. In any case, the Persians learned the first lesson of amphibious warfare: An army must move quickly off the beach, and not allow itself to be bogged down. They would not be the last to pay for this lesson in blood.

A Viking Longship

We can divide amphibious operations into two broad categories, raids and invasions. Raids are usually small and of limited duration, attempting to destroy or seize something specific before withdrawing back to the sea. In the days before modern transportation and communications, these were easy and profitable, as ships could approach undetected from over the horizon, land troops in an undefended area, then withdraw before a response could be made. The best-known practitioners of the amphibious raid were the Vikings, who would often row far up rivers to pillage towns, although it remained a common strategy until the 19th century.

Invasions are much harder because they cannot simply withdraw before defending forces arrive. The challenge of the invader is to place sufficient forces on the beachhead quickly enough to be able to win the resulting battle. The mobility provided by the sea is helpful in landing where the enemy isn't, but ships are relatively expensive, which limits the size of the invading force.

Normans going ashore

One notable invasion is that of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. He put his force ashore at Pevensey, then marched to Hastings where he erected a castle. The King of England, Harald, had been distracted by a Norwegian invasion in the north, and took nearly a month to respond. The resulting battle saw Harald dead and his army defeated, and the Normans under William soon had control of the country. This invasion is notable for its success, aided by Harald's distraction, but most invasions failed. Notable examples included the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan and the Spanish invasion of England.

Continental Marines go ashore at Nassau, 1776

The modern concept of marines goes back to the 16th century. Troops had been going to sea since ancient times, but as military forces grew more professional, a need was seen for a dedicated naval infantry force, for use in boarding actions and landings on hostile shores, instead of using normal infantry in this role. The ship's crew was expected to fight alongside them in these operations. Landings were usually raids of some sort, often cutting-out expeditions launched to seize enemy ships. An excellent picture of these operations during the Napoleonic Wars can be found in various volumes of Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series.2

The fall of Louisbourg, 1745

These marines also formed the core of invasion forces, something commonly required in the Americas during the wars of the 18th century. With a few notable exceptions, such as the failed attempt to take Cartagena, the British, often aided by the American colonists, usually swept up most of the colonies of whoever they were fighting. The biggest problem was that they had to give them back after the war was over. The best example is probably Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. It was first taken by the colonists alone in 1745, during the War of Austrian Succession, and then a second time 13 years later during the Seven Years War. That cleared the way for the British assault on Quebec, which culminated in a major crossing of the St. Lawrence River. During the American Revolution, Washington famously crossed the Delaware, taking the British by surprise.

The landing at Aboukir

During the Napoleonic Wars, the first large invasion against a defended beach occurred at Aboukir Bay in Egypt. The British were attempting to destroy the remnants of Napoleon's army he had left behind after the Battle of the Nile. General Abercromby, the British commander, planned and trained, and his landing overran the defenders, aided by apparent apathy on the part of the French. Later, Napoleon assembled a fleet to follow William the Conqueror across the English Channel, but dispersed it in 1805 to go fight the Austrians after his fleet's defeat at Trafalgar removed any chance of wresting control of the Channel from the British.

The Mexican-American War, Crimean War, and American Civil War all saw major amphibious operations, with increasing success at dealing with defending forces.

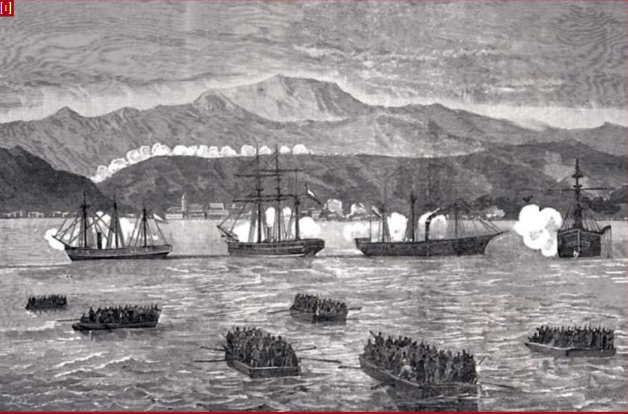

Chilean troops landing at Pisagua

In all of these campaigns, and many more that I haven't mentioned, the primary landing craft was the standard ship's boat. This could carry infantry, and some artillery and supplies, but it was not suited to quick loading and unloading, and it was totally unable to carry horses, important to provide mobility and scouting once ashore. There were a few specialized transports built on an experimental basis, but the ancestors of the modern landing craft wasn't developed until the War of the Pacific, which saw a major amphibious operation as the Chileans moved north into Peru.

By the dawn of the 20th century, the traditional amphibious operation was doomed. Improved communications and transportation allowed the defender to respond much more quickly, and the traditional, slow landing was no longer feasible. How these challenges were met will form the next part of our tale.

Comments

I'm not sure it should count as an "ancestor of the modern landing craft" as it was apparently forgotten and then reinvented, but the Byzantines and other Mediterranean powers of the 9th-13 centuries had a type of ship called the tarida/taride that is frequently described as being capable of deploying mounted soldiers directly onto a beach using a bow ramp. I don't believe anyone has discovered an intact wreck to understand exactly how this was done.

Interesting. Sort of a proto-LCT/LST. Unfortunately, nobody has yet written a good history of amphibious warfare in general, so this post had to be strung together from a mediocre wiki article and some articles in various military history journals. I had never heard of those, and I’m sort of amazed that they didn’t spread. I may look into it more.

Doing a bit of digging, it looks like they were backed onto the beach and the troops landed over the stern. This is oddly parallel to some LST concepts, although oars work a lot better than tractor props on a ship.

I'm surprised amphibious landings against prepared defenders work at all.

Small boats and landing craft are really vulnerable, disembarking troops are exposed, and bringing really heavy gear like artillery is very difficult. You'd think a successful amphibious landing would require either smashing the defenders to rubble or catching them completely by surprise, or else it would be all Dieppe all the time.

But that's not how things work. Landings against prepared defenses succeeded in both the European and Pacific theaters of WWII. So I must be missing something. But what?

There's a reason my description of those methods by analyzing Tarawa ran a full post.

Johan: Concentration of force is the big equalizing factor. Consider D-Day - the Allies landed 156,000 men on a coastline about 100km long. France alone has about 3400km of coastline, plus another 500km or so in the Low Countries. Not all of that is suitable for landing, for reasons both geographic and logistical, but if we assume that there was the equivalent of 1000km that was plausible to land on(and given all the different landing ideas that got tossed around and taken seriously by Germans, that seems reasonable), they'd need 1.5 million men deployed in fixed positions to meet force with force in a hypothetical open-field battle. That's far too many, and could never be sustained. In the actual battle, they had about 50,000 in the area.

On top of that, sea and air power can be thrown at a small area in nearly limitless quantities. The D-Day landings had over 1200 warships of various sorts and over 2200 bombers. That's a hell of a lot of fire support.

@Alsadius:

It's more than that, though. 3:1 is the traditional ratio of attacker to defender that you need for an offensive, but amphibious landings put the attacker at a big disadvantage. Firepower helps, but it ultimately comes down to lots and lots of staff work to make sure that you have enough men, supplies, and firepower in the right place at the right time and that everyone can talk to each other. An amphibious landing has a lot more moving parts than any other military operation. And you need good troops and good training to make sure you don't get bogged down on the beach.

A lot of amphibious operations attempted to bypass defenses by landing, say, outside a city, or away from the defenders, and then proceeding to their destination. They still often had failure modes.

And, really, the Trojan War is the first amphibious operation on record -- remember Hector trying to burn the Greeks' ships?

And that's what made pretty much everything here work. But as the force/space ratio got higher, and the defenders became better able to respond, it became less viable. And then there were things like Pacific islands, which just had no flanks.

Yes, and I left off the various amphibious operations during the Punic Wars, too. But the Trojan War is semi-mythical, and it didn't make the point about getting off the beaches.