The modern era of amphibious operations is usually identified to have begun with the invasion of Gallipoli during WWI. The Allies were attempting to open a sea route to Russia though the Turkish Straits between the Mediterranean and Black seas. Their initial naval assault had failed badly,1 so a plan was made to land troops to silence the guns protecting the strait.

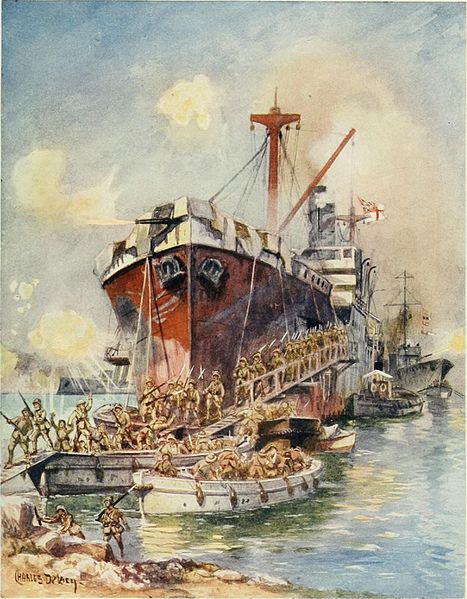

Troops unloading from River Clyde at Gallipoli

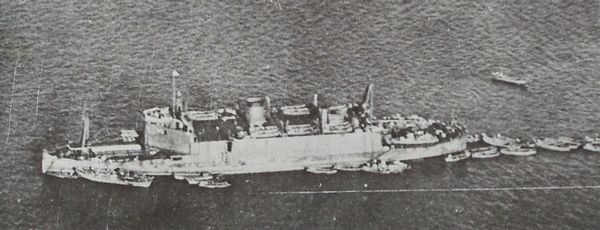

Unfortunately, the Allies did almost everything wrong. The plan and equipment had to be improvised in the month between the decision to go ashore and the actual landing in April of 1915. No serious planning had been made for large-scale amphibious operations before the war, and the five divisions assembled,2 despite representing some of the best troops available, were insufficient for the job. Like so many invasions before, this one was made in boats rowed ashore. The only specialized landing ship, River Clyde, was a converted collier intentionally grounded near Cape Hellas.3 The Ottomans near the beach were insufficient to throw back the landing force, but they inflicted savage casualties due to the lack of fire support and the general chaos. The commanders had not given sufficient emphasis to the need to move inland and the allied advance, like that of the Persians millennia before, bogged down, giving the Turks time to respond.

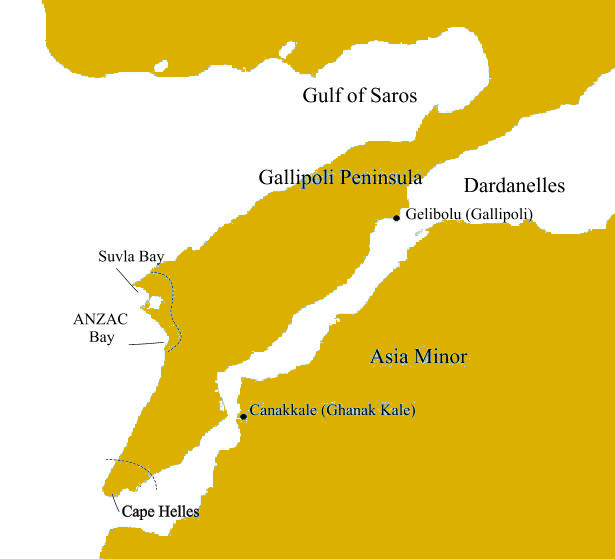

Map of the beaches at Gallipoli

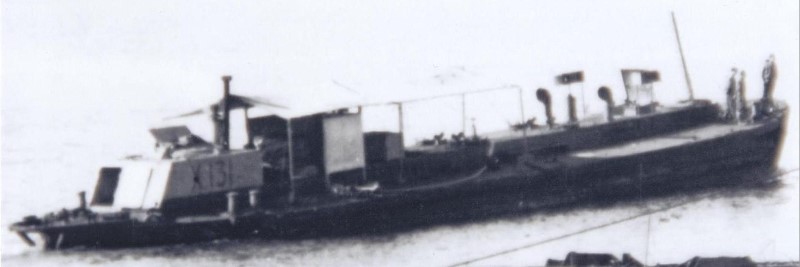

The first modern landing craft, the "X Lighter", was used during the landing at Suvla Bay in August. Built to hold 500 men each and armored against machine-gun fire, and fitted with a bow ramp to allow rapid disembarkation, they would set the pattern for future landing craft. Unfortunately, the British had learned little else, and the Sulva Bay landing failed due to lethargy on the beaches, much as the earlier landings had.

An X-lighter

The forces at Gallipoli remained perched in their narrow, craggy positions for 8 months, fighting viciously with the Ottomans. Finally, on January 8th, 1916, the last troops were withdrawn. The failure of the operation was a major scandal, and its greatest proponent, Winston Churchill, had to resign as First Lord of the Admiralty.4 The biggest amphibious operation by the Central Powers was Operation Albion, part of the German assault on the Gulf of Riga.

Troops going ashore at Gallipoli

During the interwar years, tacticians, most notably those of the US Marine Corps, attempted to digest the lessons of Gallipoli. The Marines faced a daunting challenge. In the event of the most likely war, that with Japan, they would be responsible for securing islands across the Pacific to support the American advance, and they would have to land in the teeth of Japanese defenses to do it. So they began to make plans, which would ultimately lead to the greatest amphibious battles the world has ever seen.

Troops landing in Norway from the cruiser Admiral Hipper

The first major amphibious operation of World War II was the Norwegian Campaign. The German invasion of the country barely beat the British and French, who were planning to do the same thing. Despite an overcomplicated plan with 11 separate landings, the Germans seized all but the northern section of the country thanks to unpreparedness by the Norwegians. In the north, the British annihilated their naval force at Narvik, then landed troops to retake it.5 However, the Kriegsmarine took heavy losses, most notably the new heavy cruiser Blucher.

Troops waiting for evacuation at Dunkirk

One particularly difficult aspect of amphibious warfare is withdrawing forces across a beach, which most famously happened at Dunkirk, when the British withdrew their troops from France. 338,000 men were evacuated using anything the British could lay hands on, from destroyers down to civilian excursion boats. Ultimately, 85% of the men trapped against the Channel were evacuated to the UK, although they had to abandon everything heavier than their personal weapons.

Barges being prepared for Operation Sea Lion

With the British forced off the continent, Churchill ordered preparations for a cross-channel invasion, which eventually lead to many of the ships critical to the amphibious assaults that dominated the last two years of the war. Hitler also ordered preparations for his forces to cross the Channel. In practice, the German General Staff responded by ordering their subordinates to produce paperwork for Operation Sea Lion, then going to lunch with French models. A cross-channel invasion in 1940 would have been a near-impossible undertaking even if the Germans had miraculously secured sea and air superiority. They planned to make their invasion on converted coastal barges, which could have been attacked by British destroyers steaming by at high speed to swamp them without firing a shot. As the generals probably expected, Hitler eventually got bored and decided to attack Russia instead.6

Japanese landing ship Shinshu Maru

The Japanese were leaders in amphibious warfare during the interwar years, and their conquest of the Far East had a major amphibious component. Their doctrine emphasized striking quickly at unopposed beaches, often using warships as transports, and it worked well across most of the Pacific. The only assault that was staunchly resisted was their attempt to take Wake Island, where the first landing was beaten off by gunfire from the Marines ashore before the second took the island. Their most notable innovation was the landing craft carrier, a ship designed to carry landing craft internally and then launch them by flooding an internal well deck.

Supplies piled on the beach, Guadalcanal

The US struck back surprisingly quickly with the landings on Guadalcanal in August 1942. Initially unopposed on land, the threat of the Japanese surface fleet forced the ships to withdraw before they'd unloaded all of their supplies. The result was a 6-month campaign where the Japanese repeatedly tried to throw the Marines into the sea, and the Marines doggedly held on, then gradually pushed out to secure the rest of the island.

Wreckage left behind from the Dieppe raid

Less than two weeks after the Marines landed on Guadalcanal, to gain experience for the invasion of Europe, the British and Canadians staged a major raid at Dieppe. They believed that it would be necessary to capture a port on the first day of the assault on Europe to allow supplies to flow ashore, and wanted to gain experience of what it would take. The raid was a complete disaster, over 60% of those going ashore being either killed, wounded, or captured, in large part due to difficulties getting tanks ashore to support the infantry. Better vessels would be needed for that.

Azeru, Algeria, during Operation Torch

That November, the Allies invaded French North Africa, modern-day Morocco and Algeria. It was hoped the French would welcome the Americans ashore, but they put up resistance, more so in some areas than others. This operation held the distinction of being the longest-ranged of the war, with some of the American units sailing directly from the continental US. Despite the rather messy landings, the Allies did succeed in getting a foothold in North Africa, taking the Axis forces fighting in Libya and Egypt from behind, and eventually forcing them out of Africa altogether. The difficulty of taking ports directly from the sea during this operation, combined with the failure at Dieppe, convinced them that future invasions would need to be supplied directly across the beach.

A Landing Ship, Tank unloading at Bougainville, Solomon Islands

Throughout 1943, the Allies made a number of landings. The Americans began the slog up the Solomon Islands, slowly getting closer to the Japanese base at Rabaul. In New Guinea, a new type of amphibious warfare was developed, where troops were embarked in the landing craft and taken directly to the beach, known as shore-to-shore, as opposed to the more typical ship-to-shore invasion, and used to leapfrog Japanese positions, moving along New Guinea in a matter of months. In July, the Allies landed in Sicily with eight divisions, setting a record for the largest assault force of any amphibious invasion, and quickly overrunning the island.7 In September, the Allies went ashore at Salerno, Italy. This invasion was not particularly successful, as they were expecting to meet only Italians, in the process of surrendering, and instead ran into German resistance that stalemated them for almost a year.

Next time, I'll look in detail at the Tarawa invasion, which shows most of the innovations made by the Allies during the war.

1 This is also mentioned in Mine Warfare Part 1. Interestingly, there were a few very small landings to demolish forts made as part of the early attacks, which seem to have gone well. ⇑

2 One of pre-war British troops, two of Australian and New Zealander troops, one French, and one from the Royal Navy. ⇑

3 Some forces landed at Cape Hellas, others, mostly Australian and New Zealander, at ANZAC Cove. ⇑

4 Contrary to popular belief, it didn't almost end his career. He regained office as Minister of Munitions in the summer of 1917, which is about what you'd expect of a rising star who had to be scapegoated for a failure. ⇑

5 Narvik was eventually evacuated after the fall of France, when the naval commitment to hold it would have overstressed British resources now required in the Med. ⇑

6 Any attempts to justify the unmentionable marine mammal will be mocked. The last attempt I saw to salvage it suggested that the Germans should have seized the Isle of Wight, which would have allowed them to interdict the British naval base at Portsmouth with artillery. The author seems to have not noticed the base before the Germans got ashore, and the biggest question is if the RN cruisers would have had to leave port to stop the landing, or if they could have thwarted it by firing from their berths. ⇑

7 Yes, this does include Normandy, which had a 6-division assault force. ⇑

Comments

I found the map of the beaches of Gallipoli confusing because of the inverted/vague colors - had to look the region up because it made no sense when I assumed that the blue represents water.

It was the most suitable map on wikimedia, although I agree the color choice was unfortunate. I went in and changed the land from that green to a brown.

How exactly does the 'bogged down on the beach thing' work? I get why you're vulnerable when you (or your heavy weapons) are still in the water, but what is it about the beach? Inability to tactically withdraw? That's the only factor I can think of that would be relevant at both Marathon and Gallipoli. (Well, maybe also topography?)

Also, re: Gallipoli, I was curious how the British managed to lack fire support. I mean, they had battleships! Wiki says it wasn't a shortage of guns but actually a fire control issue: the ships' fire control assumed the battlefield was flat. This is a surprising oversight, and seems like there could have been a solution with period technology--maybe there's more to the story?

It’s not just that. I may have been stretching the point at Marathon a bit (I don’t think historians are entirely certain what happened there, and I wrote that a couple weeks ago), but the basic issue is that the attacking force urgently needs to get a secure foothold ashore. To a first approximation, it needs to be defensible and have a secure rear area, out of enemy observation and most artillery fire. Anzio, the Gallipoli of WWII, is a good example of how not to do it.

To put it another way, amphibious operations are hard. One of the biggest advantages is that they can hit the enemy where he isn't expecting, and doesn't have enough troops to stop them. If they don't take full advantage of this, then when the enemy responds, they're in an indefensible position.

That’s not actually what that article says. It’s true that the FC systems assumed that they were shooting at something on the same level, but elevation in this case is how high of an angle you can fire the guns at. Plunging fire is more effective than low-angle fire, particularly in rough terrain, but the battleships in support were limited to, IIRC, 15 deg. The fact that ships are not stable gunnery platforms, and they didn’t have stable verticals in WWI was another part. That said, I suspect that the bigger issue was one of communications. With artillery on land, you could run field telephones. That wasn’t an option to ships, and radio is primitive enough that it’s probably out, too. So now you’re relying on signal flags, which are slow, and also tend to attract Turkish snipers.

I suspect bogging down on the beach is as much a logistics thing as a tactical disadvantage. A good amphibious target is a backwater where the enemy can't react quickly or fortify in advance, so that you can hit a small garrison with your whole force. That also means no infrastructure for you to capture and terrain that's not good as a port. If it were, it wouldn't be a backwater.

Loading a small boat with supplies, rowing it to the beach, unloading it, and hauling those supplies across the sand has got to use a huge amount of effort compared to even loading a horse-drawn cart and driving it along a road. Especially when most of the work is done by non-sailors, who aren't used to any of the tools of the trade, may be seasick, and are probably getting extra wet. A ton of effort to get the supplies to the very first foot of dry land - after which you still need to transport them across undeveloped sandy land to whatever front you've established, uphill all the way, probably entirely by human power. If you've landed any horses or vehicles at great effort, those are probably reserved for cavalry or scouts or generals, not logistics!

Unloading from small boats also has got to scramble any organization you have, since the largest unit on a single boat is probably a platoon, and each ship only carries a handful of boats. Your regiment or company can only land as fast as the boats can make round-trips, and the first troops ashore most likely need to immediately go into combat or start work, rather than wait to be organized.

So your whole army is exhausted, half of it is seasick, a large fraction of your army is busy trying to figure out how to be sailors or hauling heavy loads through sand, and no one is quite sure where their commanding officer is. That sounds like a recipe for bogging down to me!

If the defenders are slow enough in responding to give the invaders time to rest, organize, and create a base or even capture a port, then the invaders have a much better chance. But even then, they're still at the end of a difficult logistics chain, which limits everything.

@David W

That's a good point, although I don't think it's the full story. Gallipoli bogged during the fist wave. Anzio bogged down despite having LSTs and several recent and quite successful landings.

I think a lot of it is probably the psychological aspects of "we've done the landing, the enemy is just supposed to roll over and die now". I know that was a fairly serious problem with paratroopers. They put so much emphasis on the jump during training that in some of the early drops, they had trouble getting people to fight on the ground. Unless the emphasis is placed on the fight ashore instead of just getting over the beach, you'll have problems.

The thing about Anzio was that the landing was completely successful (total surprise, everyone on target beaches, ready to go); the fundamental problem was the size of the landing force. Two divisions, plus two-three more scheduled to arrive, were enough to form a beachhead that coul d be held; they were not enough to drive inland far enough to sever German supply lines to the Cassino front and still hold a connection with the beachhead. The Allies landed a corps when what they needed for operational success was to land an army -- the final breakout from the bridgehead used a six-division force plus another couple divisions plus of lineholding units

If the initial Allied landing force had thrust inland and the Germans had gone into immediate panicked withdrawal, it would have been a huge and massive success. If the Germans hadn't panicked, then VI Corps would have been wiped out to a man and Overlord would have been seriously questioned.

The Germans didn't usually panic.

It was more than that. The allied forces ended up holding a bunch of reclaimed marshland surrounded by mountains. They didn't hold the mountains. The Germans did, and it was a battle entirely without a rear area. Wounded men got clusters on their purple hearts when shell fragments hit them in the hospital. I'd have to read up on why the push inland wasn't carried through aggressively, but if you let the enemy have the positions that easily block your breakout, you sort of deserve what you get. And if they didn't have enough forces to do that, then everyone involved deserved a court-martial. Anyone with half a brain could look at the situation that developed at Anzio and see that it was a very bad one indeed.