The second half of the second world war saw the greatest amphibious operations the world has ever seen, and probably ever will see. Troops landed on beaches in Europe and across the Pacific, to liberate Hitler's conquests and provide bases for the final defeat of Japan by blockade and bombardment.

Troops wade ashore at Tinian

After Tarawa, the US continued its drive across the Pacific, making several landings in the Marshall Islands to gain fleet bases for the drive to Tokyo. The next step was the landings on Saipan in the Marianas. This was fiercely contested by the Japanese on both land and sea, and the Battle of the Philippine Sea delayed the follow-on landings on Guam for a month. Tinian was invaded by the same forces that had taken Saipan, after the most extensive pre-invasion bombardment in history. Engineers rapidly followed the troops ashore to convert all three islands into giant airfields for the bombardment of Japan.

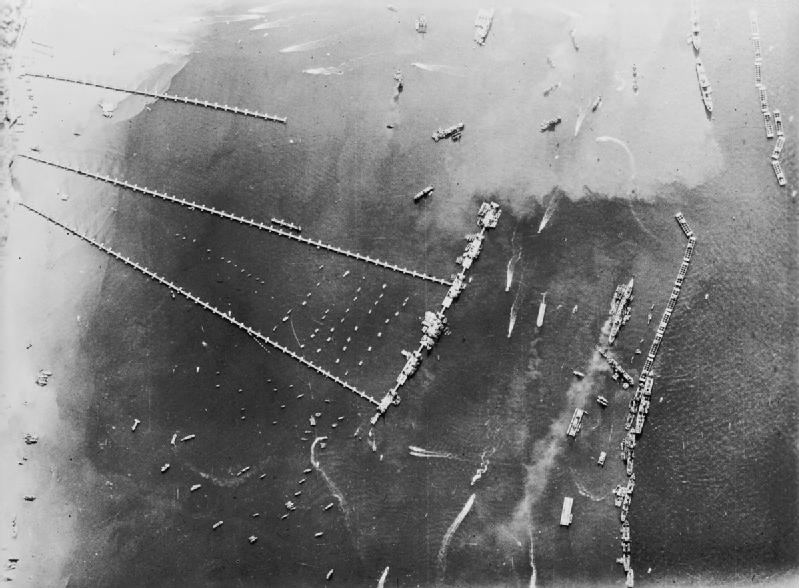

LSTs beached at Hollandia, New Guinea

Further south, Douglas MacArthur's forces moved into Western New Guinea. In doing this, they pioneered a new pattern of amphibious warfare. Instead of massive landings against heavily-defended beaches, MacArthur's men made a number of short hops, avoiding the strongest concentrations of Japanese troops. They captured air bases and ports, then pushed on quickly. These invasions were conducted on short notice, and most of the troops were carried in their beaching craft directly from embarkation to the beach. In this manner, the Allies advanced across all of western New Guinea in a mere four months.

British troops disembarking at Anzio

In Italy, the allied drive had bogged down, and a flanking landing was launched at Anzio in January of 1944. Surprise was achieved during the initial landing, but the allied commander dug in instead of pushing inland, and the result was the closest approximation to Gallipoli that was seen during WWII. For four months, the allied troops were trapped in a pocket on the beach, under murderous fire from German artillery, while ships offshore dodged German guided bombs. They finally broke out in May, and promptly made another mistake. Instead of cutting off the Germany army, they seized Rome, allowing most of the Germans to escape.

American soldiers land at Omaha Beach

The allied seizure of Rome was overshadowed a day later by the landings in Normandy, better known as D-Day.1 The first troops ashore came from the air, not over the beach. Three airborne divisions, drawn from the American, British and Canadian armies, landed behind the German lines to secure the approaches to the beaches and delay any German counterattack. The drops were a complete mess due to navigational problems, but the paratroopers were able to fight through and cause chaos behind the German lines.

Shipping off Utah Beach

At dawn that morning, six more divisions came ashore, and began to fight their way through Hitler's vaunted Atlantic Wall. The southernmost beach, Utah, was relatively lightly defended, and the Americans there took less than 1% casualties. The same was not true of the other American beach, Omaha. The two American divisions landed there faced a full German division, and the assault nearly bogged down before the German defenses were ground down. The initial objectives were not achieved for another three days.

Canadian reinforcements landing on Juno Beach

In the north, things went somewhat better. None of the initial objectives were quite accomplished, but the British at Gold Beach and the Canadians at Juno had managed to get as much as 7 miles inland by nightfall against fairly heavy opposition. The northernmost landing, by the British at Sword Beach went well initially, but then ran into heavy opposition, including a counterattack by the 21st Panzer Division. Overall, the landings went well. Over 5,000 landing craft and 500 escorts and minesweepers participated, putting 160,000 men ashore on the first day alone. By the end of June, almost a million men had reached Normandy.

DD Sherman with screen retracted

A couple of interesting innovations deserve mention. The first was the Duplex-Drive (DD) tank. One of the major lessons of Dieppe was the need for armor support to the first assault wave, so Sherman tanks were modified with a flotation screen, and fitted with small propellers. They were largely a failure, as rough seas meant that most of them sank or were very late getting ashore.

The Gold Mulberry

The second was the Mulberry. Because of the difficulty of capturing a port, it was decided to bring two from the UK and assemble them on-site, one off Omaha, the other off Gold Beach. Each was composed of obsolete ships and purpose-built caissons sunk to create a breakwater2 and special floating roadways. Unfortunately, the Omaha Mulberry was destroyed in a storm on June 19th, and the American forces were supplied over the beaches until September.

Unloading supplies at Omaha Beach, mid-June 1944

In August, the second invasion of France was launched, this time on the Mediterranean Coast. Operation Dragoon had been intended to occur simultaneously with Overlord, but a shortage of landing craft had forced it to be pushed back two months. Unlike the invasion forces in Normandy, who had been trapped close to the beaches until about the time Dragoon kicked off, those in the south managed a swift breakout, and soon the Allies were pushing against the German border. No other major amphibious operations took place in Europe,3 so we must turn our attention back to the Pacific.

Douglas MacArthur returning to Leyte

In October of 1944, MacArthur fulfilled his vow to return to the Philippines.4 The Americans landed on Leyte on October 20th, although the land campaign was overshadowed by the largest naval naval battle in history a few days later. After Leyte, the Americans took Mindoro, an important stepping stone for their final destination, the main island of Luzon. That invasion started in-mid December, and turned into the largest American land campaign in the Pacific.

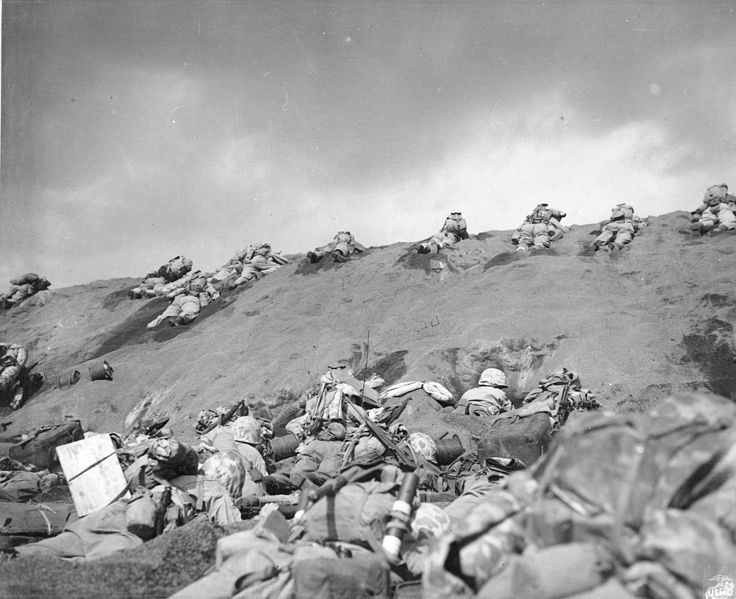

Marines in the volcanic sand of Iwo Jima5

To provide a base for fighter escorts for the B-29s that were slowly reducing Japan to rubble, the Marines landed on Iwo Jima, sparking a battle that rivaled Tarawa in brutality. The tiny volcanic island was defended by 21,000 Japanese, who managed to inflict over 26,000 casualties on the attacking Marines. This was the only one of the Pacific invasions where the defenders managed to inflict more casualties than they took, although in fairness 99% of the Japanese were killed in the fighting.

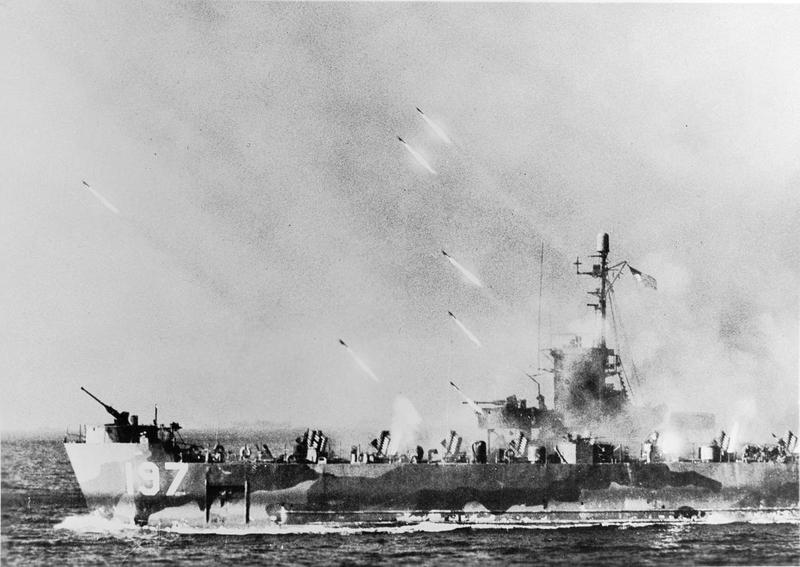

Landing Craft Infantry - Rocket bombarding Okinawa

April 1st, 1945 saw the invasion of Okinawa, the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific. Offshore, the Kamikazes took a ferocious toll on the assault fleet, although the initial fighting ashore went surprisingly smoothly. The Japanese had retreated to the southern half of the island, and had to be dug out of their positions one at a time.

Amphibious command ship Ancon during the flyover in Tokyo Bay

When the Japanese surrendered, planning was underway for an invasion of Japan itself. In practice, this would likely not have happened. The Japanese had guessed the invasion plan and were rapidly mobilizing to oppose it. As it was, the pre-war plan of blockade and bombardment would have likely have been followed once the intelligence on the Japanese response reached Washington. Fortunately, the humanitarian disaster that would have resulted was averted by the atomic bombs.

The end of World War II didn't bring an end to amphibious warfare, despite the prophecies of those who said the atomic bomb would render it obsolete. Instead, developments took place that allow naval forces to put troops ashore with unprecedented speed and precision. We'll look at them next time.

1 In fact, D-Day is the standard military term for the day of an amphibious landing, or more generally the day an operation kicks off. The actual time of landing is known as H-Hour. ⇑

2 A calm area protected from ocean waves. ⇑

3 There were a number of big river-crossings, but those are outside the scope of this post. ⇑

4 Interestingly, his famous "I shall return" was actually an offhanded comment at a press conference. ⇑

5 For the record, the photo you were probably expecting me to use here is still under copyright. ⇑

Comments

I know that at several points in the Italian campaign the Allies used smaller amphibious assaults to make end runs around the German defenses; Patton's forces did it at least twice in Sicily. Is that in any way similar to MacArthur's tactics in New Guinea?

I'd actually totally forgotten about that, mostly because I'm currently in the middle of the relevant Morison volume and haven't gotten that far yet. I don't recall it ever happening on the Italian mainland except at Anzio. From what I recall, it was a little different from MacArthur's strategy, in that the New Guinea campaign was much more "island hopping", essentially substituting jungle for open sea in bypassing Japanese positions. The stuff in Sicily was more focused on supporting the land campaign.

There are a few small landing attempts as part of various operations in Italy -- the British land some commandoes at Termoli on the east coast, and there's a commando group that lands at the mouth of the Garigliano in January as part of the first attempt to break the Gothic Line, but these are more what I would call "tactical amphibious assaults", not larger-scale operations. (They're even smaller than Patton's operations in Sicily.)

Technically, the British landing of the 1st Airborne Division at Taranto counts as an amphibious operation, too, but it's warships carrying paratroopers into a harbor, not landing craft coming ashore over an open beach, and it's a very daring operation that only works because the Italians have pretty much given up on fighting.

Also, the British do a fair amount of stuff on the Yugoslavian coast with their commandoes, including capturing some islands and briefly seizing a mainland port (they unload several thousand tons of supplies for Tito before the Germans recapture the place), but this doesn't make much stir outside the Italian theater.

Sorry, that should be "Gustav Line", not "Gothic Line" (that was the defense of the Appenines south of the Po Valley starting in July 1944).

The final 1945 offensive saw the British doing an assault in amtracs across one of the lakes in the Po delta, but maybe we should count that as more of a river crossing -- there were a lot of river crossing operations in the Po valley.

The Pacific War is my favorite bailwick, so I'm not quite as up to speed on naval operations in the Med. Sources on this stuff separated out from the general history of the war are surprisingly slim, and I didn't want to spend too much time digging. And I deliberately chose to focus on the big seagoing assaults. River crossings are a different matter (unless you're German), and the commando raids didn't seem to fit that well. Likewise, any landing direct from troop transports into a harbor is not really in scope.

So despite the disadvantages of amphibious warfare, the defenders usually took more casualties. I imagine the general pattern is disproportionate attacker losses during the landing itself, but ~100% eventual defender casualties if the attack succeeds since they have nowhere to run to?

Pretty much. I'd guess (too busy to look up numbers now) that the first day tilts heavily in the defender's favor. If the defender can then trade space for time, he can settle into a conventional campaign. If he's trapped on an island, it eventually becomes a problem of clearing terrain. While that's difficult and messy, it ultimately costs the defender more than the attacker.

@ADA: keep in mind, in the Pacific campaign battles, the Marines alone typically outnumbered the Japanese defenders by 2:1 - 5:1, and on top they had the harder-to-account support from naval guns and air. On land, you'd expect the side with a massive numerical and support advantage to win, while taking fewer casualties. Greater numbers gives you more firepower, more eyes, more angles and all sorts of related advantages that would be expected to let you do better than 1:1 in casualties.

Something similar for the Normandy landings: wikipedia tells me that the allies had about a 3:1 advantage in numbers, again not counting the naval contingent.

So it's a question of perspectives and definitions.

One perspective: The difficulty of an amphibious assault is so extreme that it can at least partially cancel out enormous differences in manpower and planning.

Another perspective: The differences in numbers brought, support available, and so on, are an option inherently provided by retaining the initiative and being on the attack. It wasn't an accident that the US chose the battles such that they had enormous advantages.

The strategic initiative is so valuable that it can even cancel out the tactical difficulties in amphibious assaults.

Probably both perspectives are valid, depending on your situation and the type of decision you're making.

I think you could also argue that the following were major innovations for D-Day:

PLUTO (PipeLine Under The Ocean): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pluto (maybe that was considered part of the Mulberry Harbours)

Hobarts Funnies: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobart%27s_Funnies (not strictly amphibious, I suppose)

Apparently the people building the huge concrete cassions for Mulberry weren't told what they were for. Imagine spending ages building a huge concrete structure according to plans and having no idea what they were.

I wrote this years ago, and suspect I picked DD Shermans and Mulberry because they were the ones directly relevant to the problems of amphibious operations. PLUTO is cool and maybe something I should write about. The funnies are interesting if you like that sort of thing, but not really in scope for this, or for me in general.