Reader Incurian has given me permission to repost his writeup on the basics of artillery, originally written for DSL in the immediate aftermath of the Ukrainian war.

Introduction

Lately there has been a good deal of discussion and speculation on what sorts of things artillery ought to be able to do in different circumstances; I'm reluctant to provide object-level answers (guesses) regarding current events, but I think this may be a useful primer for thinking about the subject and might help our discussions to be more productive.

I was an artillery officer in the US Army for a few years in the 2010s. I deployed to Afghanistan in a fire support capacity a few times. The following will be based on my narrow experiences filtered through my stupid brain, but it mostly won't be conjecture.

An M777 howitzer

The stereotypical artillery piece is a howitzer, which is like a cannon or something. I'll break out some of the different equipment categories later, but I want to start by comparing a howitzer to a four-door sedan in the following manner: an M777 is to `fires` as a Toyota Camry is to `transit`. Each is an example of a small piece of a much larger puzzle. This post will focus on how the puzzle pieces fit together rather than detailing what each piece might do in a vacuum.

Big Picture

War is, like, politics by other means, or something. The aims of a war are usually something like "kick out this government and replace it with that government in a particular area." Maybe you want to leave everything in place but the government, maybe you want to restore control over your own territory after it's been conquered, or maybe you want to conquer someone else's territory... but it's usually about deciding who is in control over a piece of land.1 Someone has to lock the other guy out of city hall, give the keys to the new guy, and make sure it stays that way. You typically need infantry (dudes walking around with rifles) to make this happen. These are your maneuver forces, their main job is to go to a place and stand on it. Everything else is a supporting effort. Examples of support are logistics (they get you where you need to go with what you'll need when you get there), intelligence (they help you decide what is the best place to go) and engineers (they help to shape the battlefield to your advantage with big tools).

A forward observer team watches as flares light the battlefield

Another category of support is `fires and effects`.2 Like engineers, they help to shape the battlefield, but from a distance... preferably out of sight and direct fire (e.g. rifles and other things that can see their target and shoot directly at it are direct fire, canons and other things that like to shoot over hills at targets they can't personally see are INdirect fire) range with lots of nasty terrain features between you. These effects on the battlefield tend to be less dramatic and permanent than what engineers can accomplish with an excavator and a bulldozer, but they have the advantage of not needing to get up close and personal with their targets (who tend to object violently to the other team existing anywhere near them). The stereotypical effect from artillery is something like destroy/neutralize/suppress the enemy using high explosives fired out of a cannon. Indeed, they tend to do a lot of this, but despite being a metonymy for brute force, cannons are capable of being more subtle. They can fire flares to illuminate a part of the battlefield (by surprise, at a place and time of your choosing, possibly in the infrared spectrum only) and smoke canisters to obscure friendly maneuver (which you may allow to dissipate after your troops are in position so they can see the enemy). Even the explodey shells are capable of a bit of nuance by using different fuze settings to make the shell explode high above the ground to maximize the fragmentation area, or a bit below the ground in order to penetrate bunkers and collapse tunnels.

A nuclear artillery shell and a crazy person

Speaking of explodey shells, they're not limited to unitary high explosives. There are white phosphorus shells for a combined incendiary/smoke effect, shells full of little mines for emplacing minefields from a distance (e.g. behind the enemy, or into an area they were juuust about to maneuver through), cluster bomb shells for saturating an area (these have shaped charges too so even a little baby bomblet can do a lot of damage to the roof of a tank), laser-guided shells, gps-guided shells, shells with rocket motors for extra range, and occasionally nukes. And that's just traditional artillery! Rockets and missiles have many of the same capabilities with longer range and a higher rate of fire.3 And that's just ground-based equipment! Airplanes and helicopters can be employed in a similar manner, and although recent advances in optics and radios have begun to blur the line between indirect and direct fire for aviation support, when it's used in coordination and proximity to friendly troops it has many of the same planning considerations as other fires.4 And if you can believe it, there's even MORE effects that need to be integrated: electronic warfare, cyber operations, information operations... and probably other stuff.

Limitations

An American Multiple-Launch Rocket System (MLRS)

By this point I hope I have convinced you that cannons are versatile tools for shaping the battlefield, and that they are only a slice5 of the myriad fires available to support the maneuver6 plan. The strengths of artillery, however, are also its weaknesses. I will discuss some of these weaknesses before discussing some of the ways they tend to be mitigated.

Artillery is big.

Therefore artillery is... slow, difficult to move over terrain, expensive, limited in quantity. Same with its ammo. You will want to have it in position before it's needed. That position is now a target for enemy artillery.

Artillery is powerful.

Therefore artillery is... not so great at making a SMALL explosion, and we want to rule city hall, not a smoking crater.

Artillery is indirect.

Therefore artillery... cannot see its own target. It needs targeting data provided to it. It needs aiming data calculated and provided to it. This means it relies heavily on other parties and needs robust communication channels.

Artillery is long range.

Very long-range artillery engages the enemy

Therefore artillery... has long distances over which small errors may multiply, reducing accuracy.7 It may take minutes before the shell reaches the target. This is in addition to the time it takes for the target location to be transmitted to the fire direction center, calculations performed, guns aimed and loaded, and any necessary approvals from higher headquarters received.8 This means the target may move away from the impact area, or friendly troops may move into it, or the mission may otherwise be overcome by events before the first rounds even leaves the tube, much less impacts on target. Your fires may arrive at the wrong place at the wrong time!

Planning and Employment

You may have inferred that there are three main players in the artillery game:

- The observer, who is typically attached to or a member of the maneuver unit. He determines the target location and requests the mission.

- The fire direction center (FDC), who is usually, but not always, located with the guns. They perform the calculations for the guns.

- The gun platoons themselves, who physically aim and fire the things.

Regardless of the equipment, you need these three elements. Sometimes two of them are combined, but if you combine all three then whatever you're doing is probably better described as direct fire.

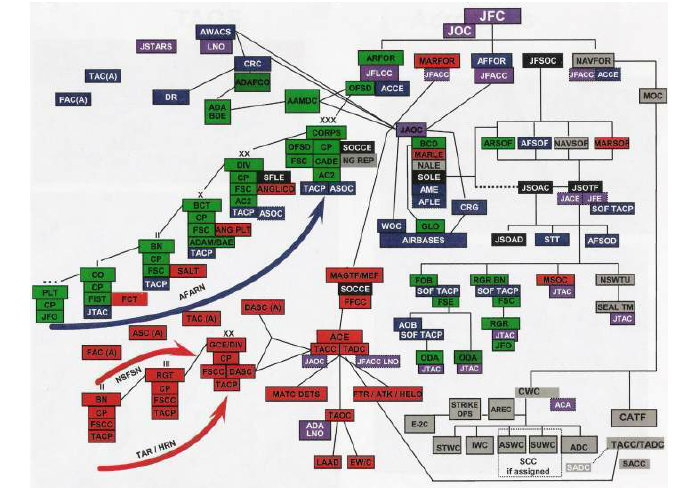

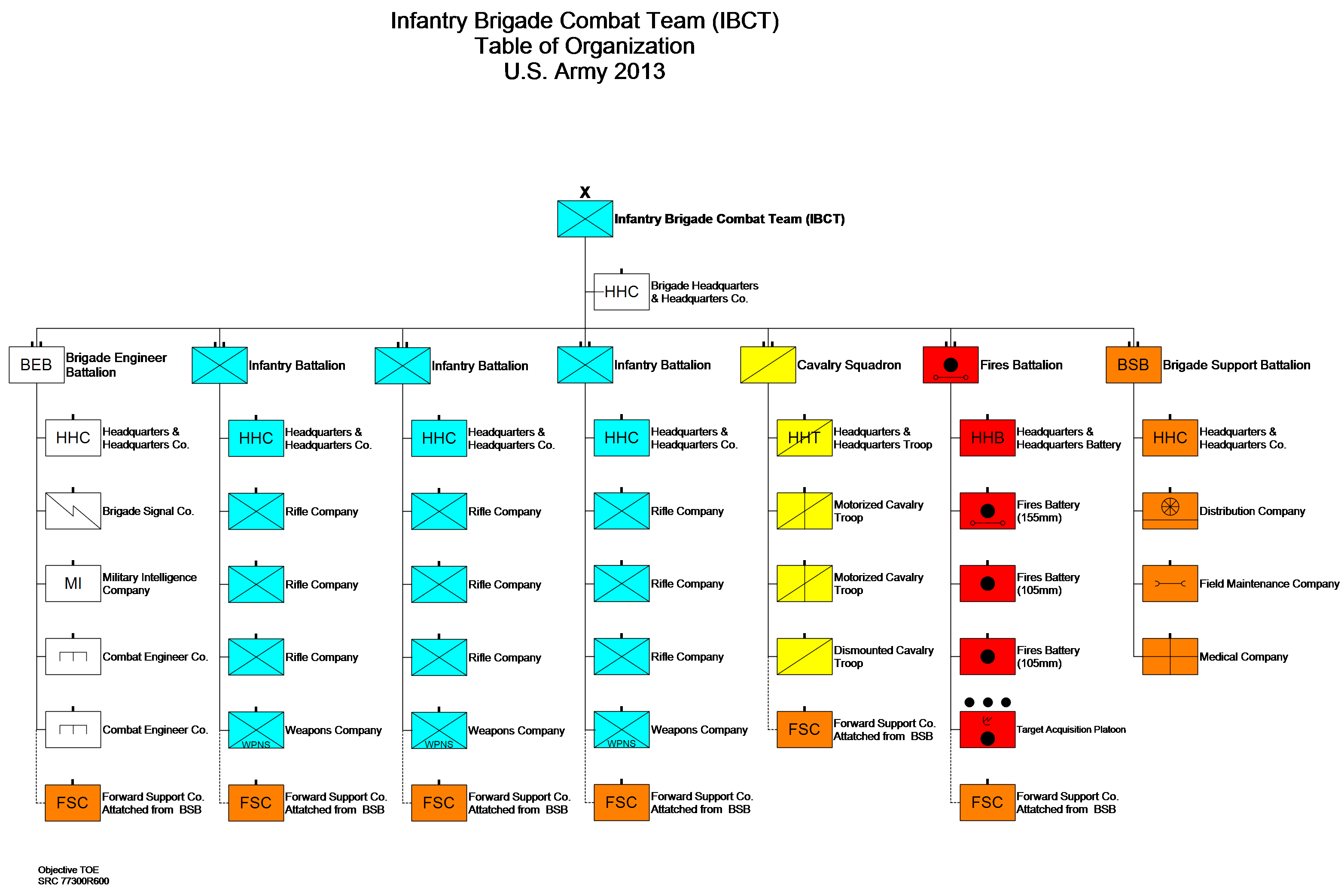

In order to maximize speed and accuracy, it helps to do some planning before the operation kicks off. We'll do this from the perspective of a battalion fire support officer (FSO) in a US Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), but the specifics don't matter. The same sort of considerations are present regardless.

If we know the location of static, high payoff targets, we can plan those fire missions ahead of time, and shoot them at the appropriate time (maybe just before the operation, we blow up their HQ so they're disorganized during the battle - but if we shoot too soon they may just replace them). Our observers will keep their eyes and ears open during the operation for high payoff targets we DON'T know the location of yet so we can destroy them ASAP.

The maneuver plan will probably imply some likely fire missions. Maybe shoot some smoke at that hilltop as our guys come around the corner, just in case they have any artillery observers there. Maybe be prepared to shoot some HE at a particular avenue in case the enemy receives unexpected reinforcements from that direction. It would be good if we had guns available to service any unexpected missions the maneuver units happen to have over the course of the operation, too.

Training with mortars

Let's take inventory of our assets (you may want to reference the org chart below to follow along). The infantry battalions (and companies even) all have their own mortars, baby cannons, that they will take along with them wherever they go. They have less range and less punch, but they are OWNED by the infantry. They can use them however they want, and the fact that they're an organic asset of the unit means the troops who are firing the things personally know and have trained with the troops requesting the fire missions. Mortars are a very RESPONSIVE indirect fire asset.

The next level asset is howitzers, owned by the brigade and operated by the artillery battalion. They have real range and punch, but they're not right there next to you (if you're an infantry dude), and they don't belong to your boss, they belong to your boss's boss. So you need to share with the other infantry battalions. Maybe the brigade will divy up the guns such that each infantry battalion has a few dedicated to them, with maybe a couple held in reserve by the brigade HQ in case they get any clever ideas. Maybe all or most of the guns will be assigned in support of whichever battalion is the main effort. Maybe all the guns will be in one big "pool" and they will be dynamically assigned on a per fire mission basis. Or some combination of all these. Whatever we decide, we need to figure out where they're going to actually shoot from. Whatever targets or units they are assigned to, they need to be in range of to support. Preferably well within range to maximize accuracy, but also preferably outside the range of enemy direct and indirect fires. Should we move the guns now? Or sling-load them under helicopters and have them arrive just in time, to minimize the chance the enemy can counter our plans. We need to get the ammo out there too. Oh, and communications. We're useless if we can't talk, so we'll need some dedicated radio channels, and probably some retransmission sites (since the whole point of indirect fires is that we can be FAR away from the target, so we'll need to artificially expand our radio range). We need to figure out how much we want to trust our observers, too. Should they be allowed to call missions directly to the FDC (if this is even possible given their radios), or should we require their missions to be approved by their fire support officer (FSO) before being passed along? Maybe we'll even require FSO approval two levels up (after all, there are lots of civilians in the area and we can't be too careful).

Attack helicopters

Above brigade is division, and division has an air combat brigade. These tend to be full of awesome attack helicopters that are fast, have excellent sensors, and a horrifying amount of firepower. They're also low and slow enough that they can almost see the battle from your perspective at the same level of detail (and much more wherever their camera is pointed). They may even have better situational awareness than you do, and may be able to provide helpful suggestions as a result. Unfortunately, they belong to your boss's boss's boss. We have to share with the whole division. Also, they're a really expensive asset that can be extremely vulnerable to certain countermeasures. Also they have to fly from their airbase which is not close to you, and they have limited fuel and therefore time after they show up to help. Maybe we can get a couple air teams assigned to us occasionally throughout the operation. If we're expecting the sort of formations helicopters are really good at killing all on their own, we'll treat them like they're practically another maneuver unit. Otherwise, we can use them as uber-flexible indirect fire, letting them squash emergencies as they pop up around the area of operations. In any case, we need to make sure our mortars and howitzers don't accidentally shoot them down. Keep them away from active guns and impact areas, and if possible the space in between.

Above division is corps. Corps has a fires brigade, with big honking rockets and missiles for murdering the absolute shit out of anything threatening enough to come to the attention of the three star general. These are mostly going to be pre-planned, or if they are targets of opportunity, it will be special forces or long range recon calling it in. They could be used for maneuver support if the bad guys were stupid enough to bunch up and hold still.

A JTAC coordinates a strike from an A-10

Corps is also the level at which air force units are assigned to ground forces. The air force is perfectly happy to provide maneuver support on an "oh shit" basis. They have liaisons at every level down to battalion, and those liaisons work hand in hand with the army fires guys. At any level, one of those liaisons (a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) in a Tactical Air Control Party (TACP)), will just hop on the radio and ask for an airplane directly, and that airplane will be put in touch with the person nearest to the action who has a radio. This is pretty neat, but it has some of the same limitations of your attack helicopters, and fewer of the advantages. If they are a fighter plane, they may have even less time to hang out and kill bad guys with you due to fuel limitations, and also because they have other work to do. They're also typically at a very high altitude moving very fast, so even with very good optics it can be difficult for them to gain an understanding of the situation on the ground.9 If your target isn't moving, and you don't mind destroying absolutely everything around it, it's an excellent option. If you target is moving, or you're not exactly sure where it is, the airplane will need to locate it itself, and this is difficult. Moving targets also have an annoying tendency to get close to things you don't want to blow up just as you get a lock.

So what?

So getting effects on target is a difficult and complicated thing even under ideal conditions. It requires multiple people acting quickly and precisely in a coordinated fashion. It also requires that those people and their equipment are put in places ahead of time where they can actually do something useful together. The broader organization needs to provide for their logistics, communications, and processes because by definition it can't be done alone. It's not hard to see how conditions on the ground and within your organization might necessitate greater or lesser centralization/flexibility.

A Soviet rocket launcher

There are tradeoffs to be made, and they're usually made by degree rather than all or nothing. For example, Warsaw Pact-type military doctrine supposedly tends to lean more heavily on pre-planned targets with centralized fire control. These targets still support a maneuver plan, but they might be focusing on the division maneuvers as a whole rather than each individual battalion. They will prefer to use massed rockets and missiles to destroy high payoff targets, but they still have mortars and howitzers at lower levels (although maybe not AS low, and maybe they themselves are more focused on lower level pre planned targets) shooting at targets of opportunity.

Are they forced to use this strategy due to crummy planning, communications, and training?10 Well, that's probably part of it, but I would consider the adversary they were designed against. NATO likes to use small numbers of expensive war machines to fight. Maybe it makes sense to optimize for countering that. By contrast, we think of the Russians as using large numbers of inexpensive war machines. It would not make sense for us to become overly reliant on targeting their key systems, because they have a lot of them and they're not that key;11 we focus on whichever ones are actively threatening us.

Postscript

In my haste to provide the "effects management" perspective from a low level army officer, I probably did not give enough due to long range targeting, particularly by other services, leaving the reader with an incomplete picture. Hopefully I've made the case that artillery is not a panacea, and it's not easy to employ. My intent was to walk back what I perceived as the incorrect focus on the bigger, more obvious fires, and bring the conversation more toward the middle. It occurred to me last night that there is probably an audience that had never thought about fires to begin with, and they might come away with the idea that the picture I painted above is more complete than it really is, so let's try to fix that.

Really heavy fires

Sometimes fires are not subtle. Sometimes you have a big list of targets far away from friendly troops. When you do, the services have a huge amount of firepower at their disposal to take advantage. Fighter and bomber aircraft can not only drop huge amounts of explosives without any input from ground pounders, they can often find their own targets (in designated play areas). Recon aircraft and other super secret squirrel stuff can vacuum up huge amounts of information that can be turned into strategic targets and handed off to cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and other aircraft. Eventually you run out of weapons or easy targets, so you let the maneuver elements do their thing while you plan for the next wave of strikes, but the effect of periodically neutralizing all the strategic targets on the battlefield should not be understated. Note which conditions must be satisfied first, and the amount of coordination required.

(wait, which side likes to rely on overwhelming fires?)

Related videos that may be more interesting now that you’re up to speed:

Genesis of the Field Artillery:

FAC(A) Demo:

JTAC Training:

Clips from We Were Soldiers that are fantastic examples:

1 Even if you just want to remove the territory from the map, to do a thorough job is a lengthy process, and in the end it makes everyone else mad and you don't get invited to the cool parties anymore. ⇑

2 There are a billion different ways of categorizing war fighting functions, but I'm choosing this way in order to emphasize the breadth of 'artillery'. ⇑

3 They can fire all of their missiles practically at once, but then it takes a million years to reload. Cannons are better for sustained fire. ⇑

4 No boss wants to hear "that's not my department." These days, artillery folks are expected to integrate ALL the different fires into the maneuver plan. ⇑

5 Nonetheless, I will use them as the primary example. ⇑

6 'But what about soviet doctrine?!' Hush, I'll get there. ⇑

7 Gunners measure angles in mils, which are approximately one milliradian (milliradian is 2pi*1000 or ~6283, mil is 6400 for convenience), or ~1/17 of a degree. One mil is one meter at one kilometer (definition of a radian). Sources of potential error from the guns: exact shell weight (varies lot to lot), powder temperature, different bore wear on the guns reducing velocity by different amounts, all the weather up to the max altitude of the round from the gun to the target. All of these values change constantly, and all of the operators are tired and under stress and possibly under fire themselves. A few mils here and there add up over tens of kilometers. ⇑

8 Fires will typically require approval from any airspace users between the guns and the target, any units in nearby areas that may be affected, the owner of the guns (may not be the same commander as the troops who requested the fire mission), and sometimes from a higher headquarters that just plain always requires their approval for that sort of thing. ⇑

9 "He's uh, in those trees over there." 'I'm at 30,000 ft going mach 2 looking through a soda straw, help me help you'. ⇑

10 It's worth noting that my understanding of the air defense situation (where I am even less of an expert, so take with a grain of salt), is the reverse. Russian armies have Man Portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADS) down to the platoon level or something crazy, while US Air Defense Artillery (ADA) is at corps and above. ⇑

11 I can't resist using a starcraft analogy: it would be stupid to focus all your fire on one zergling, and it would be stupid not to focus all your fire on a collosus. ⇑

Comments

Thank you Incurian. Most informative!

There is a really good pair of books called The Guns of Normandy and The Guns of Victory, an autobiographical account of Canadian artillery in World War II. Obviously the state of the art has changed considerably since then (e.g., MLRS, GPS, etc.), but they are still very good at getting across the artillery experience and the sorts of things they do and can do. The author started out as a forward observer and by the end of the war was composing and directing substantially larger fire plans.

I've always wondered about the practical uses for FASCAM. I guess in the 2010s that wasn't a big topic of discussion for you guys, but do you know what the cold war era doctrine was?

In sims the main use I found was plugging up breached minefields to slow down follow-on elements and keep your defenses from being overwhelmed.

I don't know the cold war era doctrine, but you're correct that in my own time the attitude toward FASCAM was "lol we'll never ever use that." I got the impression they were rediscovering/inventing new doctrine toward the end of that decade.

Literally the only place I'd seen it mentioned seriously was in The Defense of Hill 781.