WWII saw the methods used in WWI for hunting submarines extended and expanded into a dizzying array of techniques and platforms that ultimately resulted in victory for the hunters in the Atlantic, and defeat in the Pacific. I'll start our look at WWII ASW with an overview of the forces employed, then look more closely at the sensors, weapons, and tactics used.

Destroyer USS Hoel

Much like WWI, surface ships formed the backbone of the war on the submarine. The best of these was the destroyer, also used as a torpedo platform and an escort for the fleet, both anti-air and anti-surface. Due to their versatility, destroyers were in high demand; they were never available in the numbers needed to screen the fleet and protect merchant shipping. Something cheaper and slower would be required to bear the burnt of the latter task, while the destroyers worked with other warships and acted as response units for the convoys.

PC-815

The low end of the escorts were the coastal patrol craft, sometimes called submarine chasers, such as the US PC-461 and PCE-842 classes.1 These were tasked with protecting coastal convoys, but lacked the range and seakeeping to be effective in the open ocean.

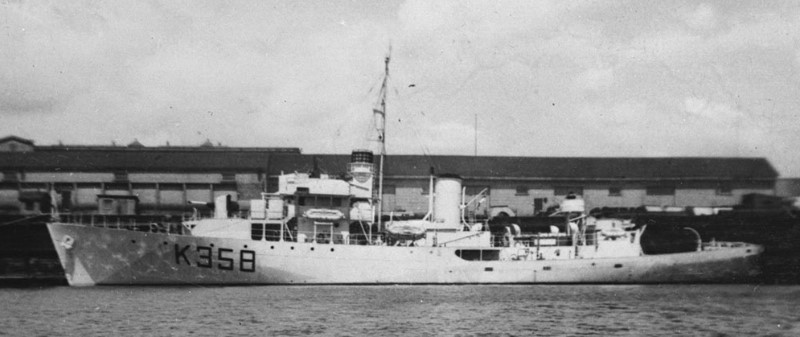

Flower class corvette HMCS Asbestos2

Originally intended to be part of this general category, the famous Flower class corvettes, originally based on a civilian whaler, were sent into the mid-Atlantic by the increasing pressure of the U-boat offensive. They could be built by small yards unable to construct larger warships, and they held the line in the darkest months of the war, until better vessels could enter service. They were not popular vessels, underarmed, wet, and slow, but the British and Canadian3 navies made good use of them.

Destroyer Escort USS England4

Above this were the ships variously known as sloops, frigates, and destroyer escorts. They were essentially budget destroyers, somewhat slower and more lightly armed, but with effective ASW armament and enough speed to hunt submarines on the surface. The US mass-produced them in great quantity, although mostly after the greatest threat had passed. Another source of this type of ship were conversions of WWI-era destroyers, usually trading boiler capacity (and thus speed) for greater endurance and additional ASW weapons.

PBY Catalina in the Aleutians

Aircraft were not particularly effective against submarines during WWI, but came into their own during WWII. Previously, they had been restricted to good weather, and to operations near the coast, but improved technology meant aircraft like the PBY Catalina and Short Sunderland could provide air cover across most of the ocean. Initially, flying boats dominated, as they could be big and heavy without the need for expensive runways. As the war progressed and airfields were built in all corners of the globe, landplanes like the PB4Y Privateer took over.

Escort Carrier USS Core

Air cover was vital to the safety of convoys, as airplanes could force down submarines at a distance from the ships. Once underwater, submarines had only their very limited batteries to maneuver on, which usually meant that the convoy could get away. Unfortunately, due to a limited supply of long-range aircraft, there was a gap in the mid-Atlantic. To fill it, the escort carrier was developed. This was a merchant ship hull modified to carry about two dozen aircraft, usually a mix of fighters and torpedo bombers. Escort carriers also served in other roles, ferrying aircraft and providing support to invasions.

A blimp on patrol over the USS Missouri during her trials

Close to shore, other aircraft provided cover. The US used blimps, which proved largely ineffective, with no kills and one blimp shot down by a U-boat. Fixed-wing aircraft were also used, ranging in size down to the Piper Cubs used by the Civil Air Patrol to spot submarines, and then call someone else to deal with them. The Germans and Japanese both used rotorcraft5 in very limited numbers, although they were not particularly effective.

USS Batfish on display in Muskogee, Oklahoma

Submarines fought each other, too. The most successful of these was USS Batfish, who sunk three Japanese submarines in 76 hours off the Philippines, thanks to codebreaking giving away the route of a Japanese submarine supply convoy. Another notable action was that of HMS Venturer, who sunk a U-boat while both craft were underwater. This is the only case ever of one submerged submarine sinking another. That said, the improvements in surface and air ASW made submarines relatively less important in that role than they had been in WWI.

U-118 under air attack

So how effective were these forces? A total of 1476 submarines were lost during WWII. 455 of them were to surface forces (30.8%), 354 (24.0%) to air attack, and 58 (4.0%) to a combination of the two. Submarines took out 69 (4.7%) while mines claimed 114 (7.7%). The balance were destroyed by accident, scuttling, or unknown causes. Different countries showed significant variations in the pattern of their losses. The US, for instance, lost twice as many boats to surface attack as they did to aircraft,6 while the Germans lost 10% more to air attack. The Japanese ratio was 4 to 1, but they lost the most of any nation to submarines, a full 18% of losses. The Soviets suffered particularly heavily from mines, while the French submarine force was mostly scuttled to keep it out of German hands.

Over the next few installments on ASW, we'll look at the sensors, weapons, tactics and methods used to fight the submarines during WWII. It's a massive field, even without going into detail on the battles themselves.

1 I'm going to be focusing on Allied forces, for the usual reasons. ⇑

2 I promise that this is a real ship, and not one I made up. ⇑

3 The RCN was at one point the 5th-largest navy on the planet, despite operating nothing bigger than a few cruisers. They focused on providing escorts for the Atlantic convoys, and did a splendid and generally unrecognized job. This post previously claimed they were 3rd, but a reader pointed me to an interesting article that proved otherwise. ⇑

4 England is pictured here in recognition of her frankly astonishing achievements in the Southwest Pacific, sinking 6 Japanese submarines in 12 days. After the first few kills, other ships were sent in first, but they proved unable to hit the targets, and England had to finish them off. This is obviously the all-time record in submarine hunting in so short a time. ⇑

5 The Japanese made use of autogryos, while the Germans got a few actual helicopters into service. ⇑

6 Counting joint as half to each ⇑

Comments

About the destroyers. It seems that almost every destroyer of every nation carried, among other weapons, torpedoes. But I have never read of a destroyer actually employing them. And against whom? Bigger ships would probably sink destroyer with their artillery before one could get close enough to launch a torpedo. Using them vs submarines feels like an overkill, and sub would probably dive before torpedo could reach it. And destroyers were never employed against merchant shipping, so that's a no too (and again, artillery would be much more convenient for that role). BTW, how were they launched? Sub-waterline launchers, like the submarines have, or directly from the deck?

Surface ship torpedoes were used extensively in the surface battles of the South Pacific. The Japanese Long Lances were deadly off Guadalcanal, although the US had some fine surface torpedo attacks later in the campaign. Later, destroyer torpedoes were used at Suriago and Samar, although not particularly successfully in the later case, IIRC. Even then, torpedoes were an important part of setting up the tactical terrain of a battle. You had to stay out of torpedo range, or maneuver frequently enough to not stay in the water where torpedoes might be. I'm less familiar with the minor surface actions that didn't involve the USN, so I can't speak to British or German uses very well.

Another use was sinking ships that were too badly damaged to take home. Guns are good at breaking things, but to put something on the bottom, you have to let water in. Torpedoes are great at that, when they work. (They're also complicated, which means they often don't.)

Some battleships had underwater torpedo tubes, but no destroyers that I know of. Destroyer torpedoes were fired from banks of tubes on deck, which usually were on the centerline and could train to either side. See here for some examples, although one of those pictures is of a class with separate tubes on each side.

Bean: pretty much every major surface battle account I've read, in both world wars, included a phase where one side or the other sent out a flotilla of destroyers to launch torpedos at the main line of the enemy (I literally today just got to the page describing this in the battlecruiser action of Jutland.) In most of the battles I've read this has been pretty ineffectual: is this in fact the general rule? Have destroyers ever been particular effective attacking larger ships en masse? Even Savo Island was mostly cruisers vs. cruisers...

As an exception, it also seems implied, though not stated, that often the real goal of sending out DDs wasn't to sink a battleship but to force the enemy to regroup/take evasion action/reposition their screen, so as to delay or hinder their ability to continue the primary engagement...how accurate do you think that was? Do you have a sense how often the purpose of destroyers was to do actual damage versus provide a threat that needed a particular answer?

The first case that springs to mind is Suriago Strait, where the destroyers sunk Fuso with torpedoes, and damaged Yamashiro pretty badly. Another case is Tassafaronga, which saw one US cruiser sunk and three badly damaged by Japanese destroyer torpedoes, despite having surprise at the start of the action.

That said, in a lot of cases, destroyer attacks were essentially suppressive fire, the German attacks on the Grand Fleet at Jutland springing most prominently to mind. I'm not going to give a numbers breakdown without a lot more research. But there were more than a few cases where destroyer torpedoes were used very effectively. Vella Gulf is another case, although it was destroyer vs. destroyer.

What book are you reading? Do remember that said attack did hit one of the German BCs. I think it was Seydlitz.

One of the things that strikes me is how close most of the anti sub battles were fought, with the combatants essentially right on top of each other. Reading about how the U boats would turn to evade in the sonar dead zone that hedgehog eventually addressed just reinforces this.

I realize there haven't been any real anti submarine operations since, except maybe the Falklands in a very half hearted way?, but what do the war games and exercises show about average engagement range today? Also, do you think this will hold up in practice?*

*Or will it end up like the "all missile" fighters in Vietnam where they actually ended up with guns and maneuvering a decent amount of the time because of weapons limitations and rules of engagement restrictions? Technology has obviously improved in the case of air to air missiles, so BVR is more feasible, but I wonder in practice how often things would devolve into dog fights or if BVR would work.

There were lots of ASW ops in the Falklands. Several whales were killed, and one submarine was depth-charged while on the surface. The British were quite scared of the Argentinian submarines, who didn't actually do that much.

Numbers are classified, and I'm hesitant to make hard guesses. Sonars have gotten a lot better, which means there's a good chance that it won't be that bad. On the other hand, if we have to start playing games in the littorals, it might be really nasty.

I actually think this is a lesson that most people got wrong. I really should write it up fully, but the basic problem in the air over Vietnam is that we refused to fight to our strengths. If you take a fighter that's designed as a long-range BVR interceptor, and then force it to dogfight, it will have trouble. If you let it work as a BVR interceptor, it might do a bit better. Interestingly, most of the MiG-21s in Vietnam had no guns, and their AA-2 missiles not only had the problems of early Sidewinders, but also the problems that lead to the prototype getting captured. What they did have was better RoE and a good C2 system. We eventually solved the C2 system and turned the tables, even if RoE remained problematic. There's a second part, which is that sometimes technology doesn't work, but it also sometimes does. The bit where we have to keep guns today with really good missiles because they were marginally useful back then, when they had only bad missiles, is just irritating. In fact, not everyone took the lesson on guns out of the war. Robin Olds refused to let his people fly with gun pods, and the USN never put guns on their Phantoms.

Yes, Seydlitz (just checked the book, which is /Castles of Steel/.) I sort of glossed over it in my reading, because the book was strongly emphasizing Beatty's predicament during the BC engagement; it only mentions in passing that Seydlitz was hit, and downplays the importance. (Not least because Massie really wants to point out how Seydlitz and her sisters were continually battered; the torpedo is sort of written off as one blow among many without any particular importance.)

Interestingly, he gives a lot more coverage to the torpedo attack on the Grand Fleet after the first BB engagement, though it does seem more important (again, as suppressive fire.)

I would be interested in that write-up!

I've obviously not put the time into it that you have, but my understanding is that the US fighters had two major problems in Vietnam, especially in the earlier part of the war:

Restrictive rules of engagement made it very difficult to engage beyond visual range, which put the US at a significant disadvantage from the start.

The tech was not so hot, in terms of kill probability, against fighters, especially early in the war. I think part of this is that a lot of the tech had been developed to counter bombers, and also that missile engineering in the late 1950s-early 1960s was not where it is today. Thus, even taking into account the limitations of the RoE, the PK against fighters was probably not very high due to the limitations of the tech. Obviously today's missiles are more maneuverable and have better sensors, so the PK is higher, and they have higher utility/faster lock times, etc.

I agree that the missiles are much better now, but I wonder how much of the drive to retain a gun is driven by air combat considerations and how much is driven by the ability to attack surface targets or (in interdiction operations against wayward Cessnas and so on) fire them in front of the target. At any rate, the amount of ammunition that they carry seems to be trending down, so maybe the DoD realizes it's not very useful but still worth having for some reason? (i.e. the F-35A carries 182 rounds internally or 220 in an external pod for the B/C versions, versus ~400 for the F-22 and Super Hornet, and ~900 for the F-15 and ~600 for the F-14 and early gen Hornet. Admittedly the F-35 uses a 25mm rather than a 20mm gun, but still.)

@Andrew

Jellicoe did the same thing in his book. I believe it wasn't a hit on anything terribly important, which sometimes happens with torpedoes. They're kind of funny beasts. I have them on my list to write about, but it might be quite a while.

@RedRover

That's pretty much it on both counts. I could go into more detail if I had references, but it will do for now.

Re guns, that's what pods are for. Firing "shots across the bow" is not a good idea if the bullets might hit anyone, which could include yourself. There are maneuvers for that. Using a gun on ground targets unfortunately puts you right in the heart of every low-level AA system known to man, which is not a pleasant place to be. And the problem with cutting ammo is that you're still carrying the weight of the gun itself, which is the majority of the weight involved. The F-35B and C are both going with pods, which is a good thing.

True!

Though I wonder if it was driven to some extent by Congressional pressure re the F-35 replacing the A-10. Going all missiles/pods may make sense from a utility standpoint, but I wonder if they put a gun on it to make Congress happier, even if it's of limited capability compared to the A-10's.

Anyways, sorry for going from destroyers to the JSF.

That's not a terrible suggestion, although the Church of the Warthog won't be satisfied with anything less than 30mm. I'd guess it was lingering Vietnam-itus, but the USN and USMC were able to make reasonable cases for why they shouln't have to participate. On the other hand, it could be service differences. The USN never put guns on its Phantoms, even in pod form AIUI. They did on the Tomcat and Hornets, but I'm not sure why. (Maybe Friedman knows the answer, but I'm still in WWII in Fighters over the Fleet.)

Bean, I imagine you have a pile of unread books at least as high as mine so forgive me if I’m adding to it, but I wonder if you’ve ever given U-Boats in the Bay of Biscay: An Essay in Operations Analysis a look. It’s a detailed quantitative analysis of one ASW campaign, but the conclusions drawn are of general interest for understanding ASW not just in WWII but in general. Indeed, the last chapter points out implications for things well beyond ASW, mainly dynamics associated with the measure-countermeasure cycle.

I’m a professional (if relatively junior) naval analyst and found it a great review of many useful abstractions and mathematical methods that you’d otherwise have to dig into the specialist literature for. Great stuff for shaping the way you think about operational and tactical concepts that frequently come up in the context of naval warfare.

With regards to RedRover’s musings on air-to-air combat, it’s very hard to say what the ROEs will look like in a future war because they will derive from whatever unpredictable political situation created the conflict in the first place. BVR combat may indeed be very restricted, at least initially and in areas where civilian air traffic is still present. That said, improvements in missile technology have benefited short range missiles perhaps even more than long range ones. Much of the devaluation of guns comes not because everyone is planning to fight primarily at long ranges but from the fact that there are now short-range missiles that combine off-boresight capability, difficult-to-fool sensor and guidance systems, and other goodies. Pilots no longer need to work themselves into the very narrow relative positioning needed to execute a gun attack.

@Directrix Gazer

I haven't read that specific book, no. I have/have read several other books on Operations Research/Analysis in WWII. I found a copy of Naval Operations Analysis in my school library, then read Methods of Operations Research, Blackett's War, and a couple of others. But I'll certainly put it on my Amazon list.

(I'm actually planning to discuss the OR side of the ASW war later on, although that post isn't written yet, and may be a while in coming.)

Wait, what? I have professionals reading? Cool.

There are two big changes that have happened since Vietnam. First, modern networks give us the capability to keep track of everything in the theater. The plane that came in on the airways from out of range and is squawking a 777s transponder is a 777. The one that took off from the enemy fighter base is a fighter, even if it's pretending to be an airliner now. Second, modern targeting pods are really, really good. I've heard that systems like Sniper can reliably ID targets at ranges above 50 nm, which is a really big difference from Vietnam.

High school or college? If the former I wish my school had had your school’s library!

I very much look forward to reading this.

Most of my colleagues have a selection of enthusiast websites they keep up on. NavWeaps, CDR Salamander, etc. In my case I’d add you (anyone who starts their discussion of warships with fire control is worth reading), the HPCA boards, and a few others. Heck, I’d say reading the NavWeaps historical/technical essays and Stuart’s stuff years ago is a big part of what first seriously ignited my interest.

I don’t often get a chance to comment, but then again I’m not often trapped in stultifying day-long logistics conferences, either : )

This is a good point. We’re is getting well outside my area of specialization, but I’d worry about the fact that such systems historically have an almost 100% rate of being totally overloaded in the early days of a conflict. There’s also the difficult-to-quantify concern of cyberwarfare measures being used to degrade the picture, which could turn out to be massively overblown but might be significant (probably not decisive, though).

College. The naval section was pretty small, but I got two great books out of it. (The other was Introduction to Naval Engineering.) My high school library was pretty bad.

Mine too, actually.

Ouch. That does sound painful.

Good points. It's certainly not a panacea, but getting this stuff working right was a major part of turning the Vietnam air war around. If the situation is more Vietnam-like, and less total war, then they'll probably have time to get the bugs sorted out. And if it is total war, the airliners are going to be staying far away.

Also, I imagine the Vincennes/Iran Air shoot down weighs fairly heavily on the minds of whoever sets the RoE in events short of all out war.

I’m sure it does, although that case is rather more complicated than it might appear, and probably wouldn't happen today.

I agree that the Vincennes was more complicated than the press would have it (surprise!) but bad symbology/system sync would seem to improve the case for visual ident, or am I misunderstanding your point? I'm sure the current version of AEGIS incorporates some of the lessons from the Vincennes incident, like having a symbol for civilian targets, but I think the underlying risk is still there, particularly if, as was the case with Vincennes, the target takes off from a civil/military dual use airport.

Vincinnes was kind of a perfect storm of symbology problems, other HFI problems (some modern network specifications state that you aren't allowed to repeat track numbers for 24 hours) and a crew that wasn't doing its job right. I obviously won't claim that it will never happen again, but I think the chances of a repeat are actually pretty low. We'll find new and exciting ways for our systems to fail instead. The relevant tech has come a long way in the last 30 years. Of course, the decision-makers may not know that.