In many ways, Jutland was both the first major naval battle shaped by the development of aviation and the last one unaffected by it. Aviation considerations shaped the time and place of the battle, but despite efforts by both sides, aircraft made no impact on a tactical level. As such, it's worth taking a closer look at the aviation operations surrounding the battle.

By 1916, the Germans had at least the first inklings of a doctrine for the use of the Zeppelins in support of the fleet, and they formed an important part of Scheer's plans in May. As part of his attritional campaign against the British, he would use a raid on Sunderland, in northeastern England, to draw the British fleet past his U-boats, hopefully costing them some ships. Even better would be a chance to catch a detachment of the fleet by itself and defeat it in detail. Zeppelins offered a platform capable of making sure that the High Seas Fleet didn't blunder into the entirety of Jellicoe's force. Unfortunately, by the time his ships were ready to sortie, southwest winds1 meant that the Zeppelins couldn't participate. Scheer chose to abandon the Sunderland plan and instead send his force to sweep the area around the Skaggerak, the strait separating Denmark and Norway. The British, aware of the German sortie thanks to good intelligence work, sent Beatty and Jellicoe to intercept.

A Zeppelin over the High Seas Fleet

By May 31st, when Scheer actually sailed, the weather had moderated some, and five Zeppelins were ordered to provide distant cover for the High Seas Fleet. Unfortunately, the weather was still too bad for an early departure, and when the two fleets met in the greatest naval battle of the war, the Zeppelins were still well to the south. Two airships picked up reports from the battle and attempted to aid Scheer, but poor visibility kept them from doing so. As the first airships returned, a second group was dispatched to take up station on the morning of June 1st, and two of them, L22 and L24, flew undetected over the frantic night action. As dawn broke, the latter airship began to send in a stream of contact reports for a group of ships in a bay on the Danish coast. Unfortunately for the Germans, there weren't any British ships there, and historians are still not sure what L24's crew saw.

L11

Another one of the Zeppelins, L11, turned in a better performance. Her crew first spotted the British fleet around 0400, and radioed a report back to Scheer. The airship had trouble keeping contact in the twilight, but the British found it easy to see silhouetted against the dawn sky, and opened fire. Every gun in the fleet, from AA guns up to full broadsides from the battleships,2 opened up on it. None of them hit, but some burst so close that the crew was buffeted about. Visibility was so poor that some of the 21 ships firing on L11 could only be seen by their muzzle flashes, but after an hour, the airship was forced to high altitude and lost contact with the British. Despite the poor conditions, the crew was able to give accurate reports of the numbers, type, speed, and course of the ships below, although their value was rather compromised by navigational errors of 25 to 30 miles. Scheer, believing the reports from L24, thought that these ships were reinforcements from the Channel, and declined to engage.

HMS Engadine

But the tale of the Zeppelins is only half of the story, as the British also tried to bring aviation assets to the battle. Beatty and Jellicoe each had a seaplane tender assigned to their force, Engadine and Campania respectively. Engadine was a former cross-channel ferry that had been fitted to carry four seaplanes, along with all of the equipment to support the operation of the fragile aircraft of the day.3 Unfortunately, she had no way of launching them except to stop and lower them into the water, which relied on calm seas and made working with the fleet very difficult. Campania was a former liner and holder of the Blue Riband that had been on her way to the scrapyard when war broke out. In an attempt to remove the need to stop and hoist out airplanes, Campania was fitted with a sloped flying-off deck forward. In fact, an early deck had proved too small, so she was modified, with her forward funnel divided in half and the deck passing between the two sides. This worked reasonably well, the floatplanes riding on a wheeled cart that fell into the sea, and the large Campania was able to carry up to 10 planes.

Campania

On May 29th, Campania was conducting experiments with the newly-fitted flying-off deck, and the next day, she anchored well away from the rest of the Grand Fleet. For security reasons, all British harbor signalling was visual, and Campania missed the order to sail, only realizing her mistake two and a half hours later when the harbormaster asked when he could close the boom. She set off, but was soon ordered back to port by Jellicoe, who was concerned about the unescorted ship's vulnerability to submarine attack, and didn't believe she could catch up with the fleet in time. Engadine, however, had sailed with Beatty, bearing four planes: two Short 184 two-seat reconnaissance floatplanes, and two Sopwith Baby single-seaters intended to shoot down any marauding Zeppelins.4

Engadine and Galatea with other ships during the earlier raid on the Tondern

On May 31st, Engadine was the lead ship of the entire British fleet, 4 miles ahead of the scouting line of light cruisers. This seems odd, but it was a consequence of the need for the ship to stop and hoist out her floatplanes. Besides costing half an hour or so, while the fleet forged ahead at something like 15 kts, it also could be disrupted by the turbulent wakes of ships ahead of the carrier. Fortunately, the first ship to encounter the Germans was the light cruiser Galatea, at around 1520.5 This first encounter was to the northeast of the British, and Beatty turned southeast to try to cut them off, then ordered Engadine to launch a plane to scout to the northeast, where Galatea reported a great deal of smoke.

Rutland of Jutland (left) aboard Engadine

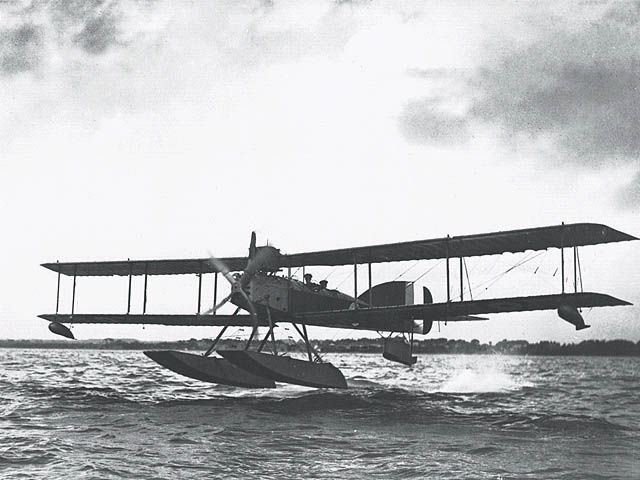

One of the Short 184s was quickly made ready, and at 1607, it was hoisted over the side, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Fredrick Rutland with Assistant Paymaster George Stanley Trewin as his observer.6 A minute later, the Short was airborne,7 and Rutland flew a course of about 10° under the 1000' cloud base. Unfortunately, this took him too far north to see anything particularly useful, although he encountered a trio of German light cruisers. Trewin was able to accurately identify them after closing within a mile and a half and coming under heavy fire, and transmitted a report back to Engadine, including an update when the Germans turned south to fall back on Hipper's main body.

A Short 184

Unfortunately, the second part of the plan, where Engadine would pass the message to Lion, failed completely. Both visual and radio signals went unheeded in the mess that was British communications at Jutland, meaning that the first participation of ship-borne aircraft in a naval battle amounted to nought. To make matters worse, at 1645, a fuel pipe on the Short's engine broke, and Rutland was forced to alight on the water. This kind of failure wasn't a particularly uncommon occurrence at the time, and he was able to improvise a repair and get back in the air. Engadine, on being informed of the failure, ordered him back home. By this point, Beatty was engaged with the Germans, and no further orders were given for Engadine to use her aircraft. This was probably for the best, as the Germans had apparently begun to jam Trewin's radio, and visibility was low enough that the planes wouldn't have been able to safely scout.

Warrior sinking

Engadine managed to stay clear of the clashing fleets, and after the first encounter between Jellicoe and Scheer, was dispatched to stand by the badly damaged armored cruiser Warrior. During the night, she took the bigger ship under tow, but Warrior’s injuries were mortal, and her crew transferred to the seaplane carrier around 0900 on June the 1st. During the transfer, one of Warrior’s guns punctured Engadine's hull, although the damage was quickly patched. A bigger issue was the 675 men brought aboard, who had to be carefully distributed to avoid compromising the ship's stability. Rutland distinguished himself during the transfer by diving over the side against orders to rescue a wounded man who had fallen, and was awarded the Albert Medal.8

Jutland is often seen as the last of the big-gun battles, and rightly so. Never again would massive fleets of capital ships clash without the intervention of the aircraft. But as it was the last of the old, it was also the first of the new, with Rutland's flight showing the way for the rise of the carrier a quarter-century later.

1 Blowing across the line the airships would have to travel. ⇑

2 I have no clue why they did this, or how they expected to hit. It wasn't unprecedented, though, as a number of monitors had been used in a similar role against Zeppelins in defense of London. Of course, it didn't work there, either. ⇑

3 Besides a lot of mechanical equipment to keep the engines running and a radio to pick up and relay messages, this included a darkroom and a set of homing pigeons, which served as a backup to the seaplane's radio. ⇑

4 Campania carried seven Babies and three 184s, along with a kite balloon. Her seaplanes were apparently intended more to attack Zeppelins and scout for hostile submarines, while the kite balloon handled close-in recon work. ⇑

5 As usual, I'm using GMT+1, to match the German track charts, instead of GMT, which British sources generally use. ⇑

6 Observers at the time were chosen primarily for being light and knowing Morse Code, and didn't have to be pilots or even part of the Royal Naval Air Service. ⇑

7 Two books contain wildly different accounts of this. David Hobbs says that another pilot was already in the plane, which was warmed up and ready to go when the order came through, and could have been airborne probably around 1545 if Rutland, the senior aviation officer aboard Engadine, hadn't taken the spot. R D Layman says this was a creditable performance, with the fastest time for a launch in harbor being around 20 minutes. ⇑

8 Rutland, known afterwards as "Rutland of Jutland", was an interesting character. In the interwar years, he became a spy for the Japanese, giving them information on carrier aviation, and ran a business in Honolulu in the late 30s and early 40s. He returned to Britain in October 1941, and was later interned as a possible enemy agent. In 1949, he committed suicide. ⇑

Comments

So how does sending carrier pigeon messages from a sea plane work? I don't think you could send a message back to the ship, as I expect that pigeons will only home to a fixed location. Presumably they return to a pigeon loft in Britain that the relays the message back to the ship via radio?

When Rutland was spying for Japan, how cordial was the relationship between the UK and Japan? Would it be the equivalent of a contemporary US officer spying for a NATO ally, or closer to spying for China. From the perspective of the spy, I suppose it doesn't matter, as it's not like his handler is under any obligation to be honest about who the information is being passed on to, but it might affect the attitude of the British once the treachery is discovered.

No, it was apparently possible to use homing pigeons from moving ships, or even from mobile field stations. Not sure exactly how, and it probably depends on the ship/station not moving too much, but it is possible.

Anglo-Japanese relations were relatively cordial early on, but got worse through the interwar years. Not a NATO ally, but someone like, oh, Brazil or Mexico early on. China by the end.

Britain and Japan had a formal alliance from 1902 through the early 1920s, and Japan had joined the Entente side of WW1 in part due to the treaty, although their involvement seems to have been peripheral: a successful siege of Germany's naval base in China, some uncontested seizures of German minor possessions in the Pacific, and anti-commerce-raider patrols in the Pacific and (towards the end of the war) the Mediterranean.

The alliance fell apart after the war because Japan's expansionary ambitions were conflicting increasingly with Britain's existing Empire, and because one of the main original British motivations for the alliance (preempting Japan from allying with France and Russia against Britain) was firmly moot.

Depending on when exactly Rutland was spying for Japan, I expect it would be somewhere between a modern American spying for Saudi Arabia or Turkey (technically a friendly country, but the kind of friend who almost makes you prefer your enemies) or an American spying for the Soviets in 1946 or 1946 (an erstwhile ally that's rapidly becoming a major strategic rival).

I wonder what WWII would have looked like if the British hadn't let their alliance lapse.

Getting rid of that alliance was an American condition for the Washington Treaty, so things would have been very different if it had stuck around. Not sure exactly what that would look like, though. There was talk of not renewing it before WWI, and I suspect that natural pressures would have broken it sometime in the 20s even if not for the Americans. The Japanese were the leading opponent in British war planning during that entire decade, and I don't think that would have really changed even if the alliance had stuck around on paper.

I'm impressed with those homing pigeons. It's reminiscent of Noah and his dove Ü

With regard to the spying, while in hindsight it's easy to see the US as a steadfast ally of Britain, and Japan as a major threat, I wasn't sure how clear the picture was in 1920. If (like me) you don't know much about the history, you could imagine some British support for helping to strengthen the Japanese, seeing them as a counter to American dominance. It wouldn't be much stranger than the Canadian defence scheme #1.

Technically, it's exactly like Noah's dove, because doves and pigeons are the same thing. (I only know this because I went to the national pigeon museum, which is not far from my house.)

@bean Well, how was it? Did it have a big culinary section?

It did not, because it was run by pigeon fans. Lots of talk about racing pigeons and homing pigeons. Decent enough, particularly because it's free, but not worth going far out of the way for.

Ah, in England it's fairly well known that they are the same, to the extent that rock doves tend to be referred to simply as 'pigeons' but maybe they aren't as common in America? But yeah, I didn't realise that they could actually navigate like that.

Thinking about it a little more, of all of the beasts used in war, elephants and horses hog all of the glory. You so rarely hear of the vital work done by the ass, the hound, and the pigeon.

The Dickin medal went to more pigeons than to any other type of animal, Cher Ami was well known in the US during the interwar period.

@alexander

To quote an ok book, "Releasing the pigeon involved tossing it out of an aircraft moving at something like 150mph. This was no doubt character forming for the pigeon."

@bean

I can imagine a world where without charles evans hughes, there's no naval treaty in the 20s. That leads to a proper naval race that Japanese straight up lose. We go into the 30s with a UK that has more of a naval lead than it had historically but feeling worse about it and a japan more behind but feeling less angry about it. Both result in them clinging to their alliance.

That said, interests generate allies, not the other way around. The forces pushing Japan to expansion aren't going to just vanish, and I see it as extremely unlikely that the US would manage to keep interest in a naval race big enough to push the japanese and UK together through the 30s.

I'd love to know more about the early radios in airplanes. I didn't realize WWI airplanes had any kind of radio!

@cassander

I don't think the British were actually interested in a naval race. They simply didn't have the money, and the structural gaps with Japan were already starting to show. Hughes wasn't that unique.

@Kit

I don't have many details to hand. They did have radios, but not very good ones. They'd use a trailing antenna which had to be wound out by the radio operator, and could really only talk to ground sets.

I learned about the old WWI radio aircraft reading my Biggles books when I was in primary school.

On the subject of an Anglo-Japanese alliance against America: I've seen a pretty persuasive argument from a guy I trust that Great Britain and America stopped being in a rivalry after a) the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty and b) the Boer War. Both sides recognizing the other's sovereignty in their domains (South America and Africa, respectively) meant that neither one had claims that was going to drive them towards war. They might not like each other, and certainly might not always work towards the same ends, but at the end of the day, it was never going to be enough of a problem that war is declared and battle come down, to quote a certain Briton.

It's hard not to see Japan and Britain always falling out at some point (rising Japanese militarist ambitions were always going to be a threat to British territorial possessions in the Pacific). Maybe things in WW2 get interesting if America is a lot more isolationist and decides that they don't care about defending British colonies and let the Japanese know they aren't going to defend them no matter what, but that's not a scenario where you end up with an Anglo-Japanese alliance against America either.

Without doing much research, I would guess that the most likely thing to create a strong Anglo-Japanese alliance in the 1920s/1930s is a Soviet Union that is much more threatening to the West than we have.

@bean

I think that if the US had really committed to second to none outside the treaty system, the UK would have made an effort to keep a few steps ahead. At the very least, they'd have had to match the South Dakotas and Lexingtons and kept more older ships around. And then the US would launch another round and the same thing would happen. Or it would get bored and give up. Probably the latter. Remember, the UK didn't really agree to actual parity in the treaty, they agreed to parity in principle but with several exceptions and the knowledge that the US wouldn't build up its cruiser fleet to the level they would.

@Blackshoe,

I can easily see the US deciding that defending British colonial interests wasn't worth picking a fight with Japan. I can stretch a bit to imagine the US deciding that maintaining the Open Door in China in the face of sustained Japanese aggression wasn't worth what it would cost. But what about the Philippines and Guam? I think Japanese territorial ambitions were pretty inevitably going to bring them into conflict with the US as well.

Also, how do you see the USSR in the 20s and 30s threatening British interests in a way that pushes them into alliance with Japan? The only thing I've been able to come up with is an earlier, and much bigger and more successful COMINTERN intervention in China in the 20s, leading (somehow!) to the CPC rather than the KMT uniting China in the late 20s and (somehow!) consolidating their victory without another 20 years of civil war. Then the newly-unified China, with a huge set of historical grudges and an alliance with the Soviets (and maybe also the US? I could see FDR being on board with this), might perhaps threaten the Asia-Pacific holdings of European colonial powers enough to drive them into alliance with Japan. But this is pretty deep into Alien Space Bats territory.