Reader Suvorov has contributed another part in his series on Confederate commerce raiding.

While the Confederacy’s brief flirtation with privateers was quickly choked off by the Union blockade, the Confederacy’s long-term plans for dedicated naval commerce raiders continued to move forward. Their domestic program proceeded somewhat haltingly – their first commerce raider, the Sumter, was not ready for action until the summer of 1861, by which point the Union blockade was tightening around the Southern ports, including New Orleans, where the Sumter was being refitted – to the frustration of one Raphael Semmes, who had been placed in command of the vessel towards the end of April and had hoped to escape to sea before the blockade was in place.

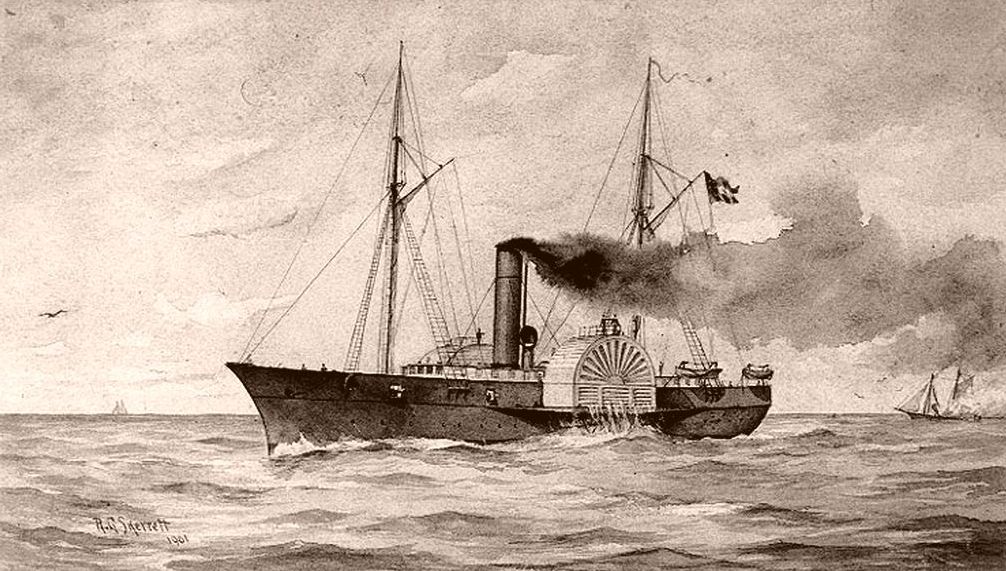

CSS Sumter

Semmes was a major exponent of commerce raiding, and the war would give him a chance to put his theories in action. When the steam-powered sloop Brooklyn, assigned to the New Orleans blockade, left its post in pursuit of a quarry, Semmes escaped New Orleans to unleash his “defective little Sumter” on Union shipping. However “defective” the Sumter might have been, it captured eight vessels within a week on its initial cruise between New Orleans and the Cuban port of Cienfuegos—a victory that was significantly dampened when the Spanish authorities, concerned about their perceived neutrality in the conflict, returned most of his prizes to their original owners. (The fact that Semmes had grabbed three of his prizes almost in the mouth of Cienfuegos’ harbor probably did not dispose the Spanish authorities kindly towards Semmes’ attempt to leave his prizes in that port indefinitely.)

Raphael Semmes

Semmes then proceeded to South America, where his successes proceeded in much the same pattern: his first prize was recaptured attempting to run the Union blockade, and his second again freed by the Spanish government of Cienfuegos. However, Semmes had single-handedly succeeded on stirring up a panic: the next ship he captured was empty, because Semmes’ exploits had already made merchants reluctant to send their goods by American ships. By this point, the Sumter was not the only Confederate commerce raider in operation: she had been joined (conceptually, but not logistically) by the Nashville, which saw much less success on her first cruise—only capturing two prizes—but gave U.S. warships the slip twice, once in England and a second time when she ran the Northern blockade to reach a safe Southern port. Although much less materially damaging than the Sumter, the inability of Union ships to capture her proved to be a major embarrassment.

CSS Nashville

Dodging his own share of Union naval vessels, Semmes bagged several more prize ships and sailed to Europe, where he was eventually cornered by a combination of Northern steamboats and by Chargé Perry, the U.S. consul in Gibraltar, who convinced local coal businesses that dealing with Semmes would negatively impact their business prospects. Rather than face nearly certain capture, Semmes decommissioned the vessel on April 11, 1862 and escaped to London, having effectively terrorized Northern shipping off the coasts of three continents.

USS Tuscarora and Kearsage keep watch on Sumter in Gibraltar

Semmes was not yet through with commerce raiding, and his early adventures in the Sumter are overshadowed by his later voyage in the Alabama. But while Semmes had been cruising about in a converted vessel, the Confederacy had been attempting to procure purpose-built vessels from abroad to serve both as commerce raiders and as blockade-busting ships of the line. We’ll discuss the Confederate’s covert overseas shipbuilding program in the next installment of this series.

Comments

Is there a reason why the post spells Sumpter with a P throughout? Presumably it was named after Fort Sumter (no P), which was named after Thomas Sumter (no P)- and every reference I can find also spells it without a P.

Confusingly, there was also a USS Sumpter (with a P) during the Civil War, which I imagine was named after the word for a pack animal. Not to mention at least one another Confederate ship called Sumter- an unarmed steamboat chartered by the Army and sunk by friendly fire from Fort Moultrie in 1863.

As far as I can tell, none of these three ships ever met, though Union intelligence confused the steamboat for the commerce raider and reported that the latter had been sunk.

My guess would be that this was the tail end of the era of nonstandard spellings, and Suvorov picked a less-used variant. That's how it came to me, so I just kept it as-is.

Thanks for noticing, @AlphaGamma

As flattering as bean's explanation is, I checked the original text and it looks like I originally used "Sumter" throughout, and it's currently used both ways in the text of this post. I think it's a typographical error I made during the editing process.

I don't want to make more work for bean, but I think it'd probably best if it's corrected.

Should be fixed now.