In our prior installment, we covered the Alabama’s fight with the Hatteras – a rare example of a Confederate raider fighting anything remotely resembling a proper warship. But, while the Alabama is probably the most famous of the Confederate raiders, the first of the Confederacy’s purpose-built raiders, the Florida, had slipped out of Mobile and past the Union blockade.

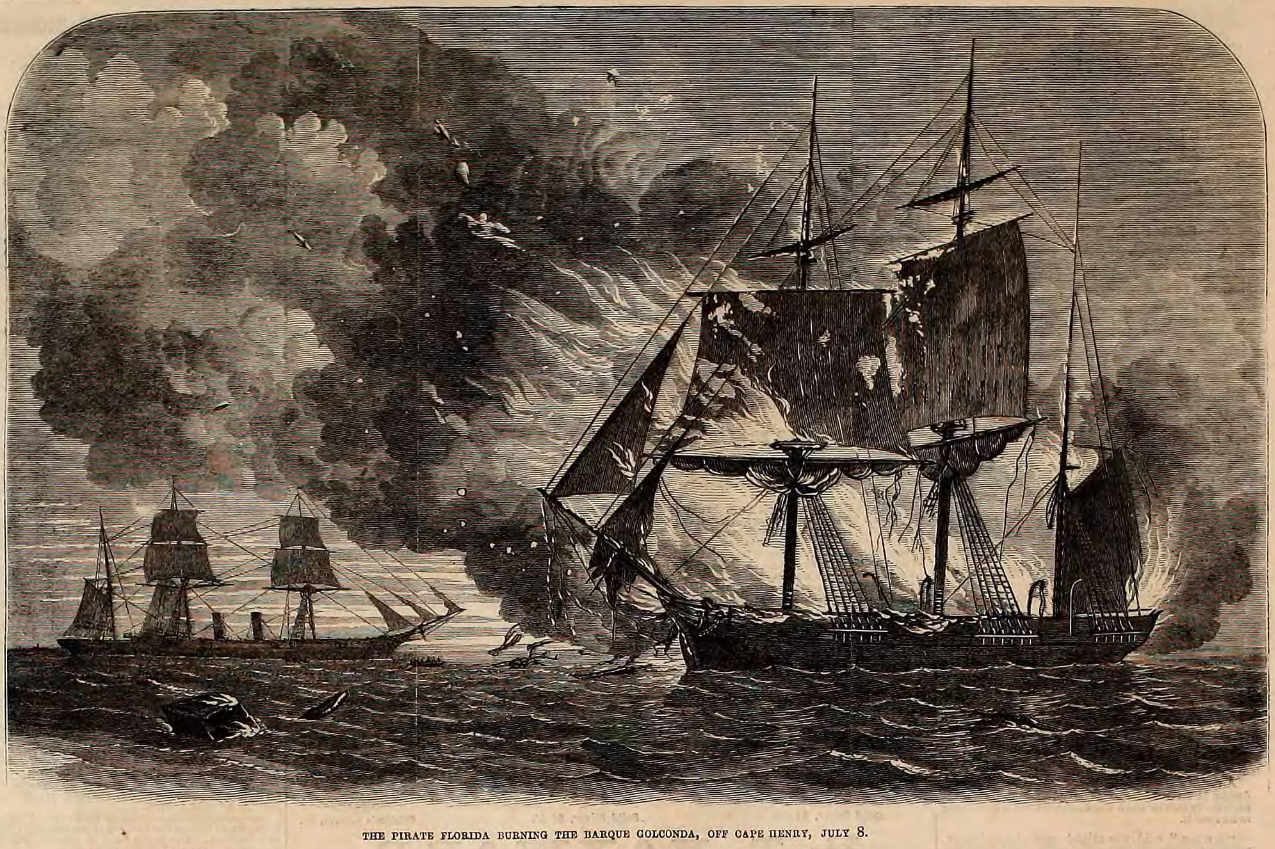

Florida burns a prize

This escape, along with Semmes’ defeat of the Hatteras, compelled Welles to remove several ships from the blockade in an attempt to capture or sink the commerce raiders, but to no avail. The Florida left a trail of burned prizes across the Atlantic, keeping several ships as prizes and outfitted them as makeshift commerce raiders in their own right, multiplying its impact. These ships, the Lapwing and the Clarence, had their own bizarre adventures: the Lapwing captured a ship full of guano, while the Clarence, commanded by Charles Read, set out to attack the ports of Hampton Roads or Baltimore. Taking a string of prizes, Read transferring the rebel flag from ship to ship as he captured more suitable vessels before sailing into Portland, Maine, and stealing the revenue cutter Caleb Cushing. The Cushing was quickly overtaken by an impromptu pursuit fleet and set alight by Read, who then surrendered. The Lapwing suffered the same combustible fate when she became unseaworthy.

Confederate efforts in Britain had produced two additional raiders for Welles to contend with, as well: the CSS Georgia and the CSS Rappahannock, both purchased not by Bulloch, but by another Confederate operative, Matthew Maury. The Rappahannock, which was a former Royal Navy vessel bought at auction, repeated the Alabama’s exploit, escaping during a “sea trial,” but her engines failed and she drifted ashore in France, where she remained for the duration of the war. The Georgia—a modern iron-hulled screw-powered steamship—saw more success, capturing nine vessels throughout the course of 1863. However, she failed to live up to Mallory’s instruction that commerce raiders “be enabled to keep the sea, and make extended cruises,” for she lacked a full sail, and her iron hull required the frequent attention of a shipyard. Mallory presciently worried that “want of a hoisting screw would be a great bar to her usefulness.” When her hull was fouled by ocean growth in the autumn of 1863, she was unable to procure a needed drydock in a timely manner, and ultimately seized by an American warship in the summer of 1864.

Wachusett tows Florida out of Bahia

The Florida’s career, however, continued unimpeded by Union warships or the technicalities of English and French neutrality law alike until it docked in Bahia, Brazil, in the fall of 1864. There, on October 7, the USS Wachusett steamed into the neutral Brazilian port, and, showing unusual (and in this case improper) initiative, rammed the Florida, which surrendered. The Wachusett managed to avoid being attacked by Brazilian forces in the harbor and towed the Florida off. The commander of the Wachusett was court-martialed and pled guilty for his violation of Brazilian neutrality, but was kept in the Navy by Welles. Brazil demanded the return of the Florida, but the ship was rammed by a transport vessel (allegedly, a very convenient accident) and sank.

Almost simultaneously with the unlawful capture of the Florida, the British trade vessel Sea King, secretly purchased by Bulloch, was armed and recommissioned as the Confederate raider Shenandoah. She was sent forth specifically to strike at the relatively un-molested Northern whaling fleet in the Pacific. “The whale fishery,” Mallory noted in a letter to Bulloch, “is almost exclusively a New England interest, and a very sensitive one. A ship is usually owned and fitted out in shares by numerous owners…thus the destruction of a whale ship usually touches the pockets of many families in the middle walks of life…” Noting that whaling had already declined to its 1840s levels, and that the Alabama and her peers had already chased most whalers from the Atlantic, Mallory viewed a successful strike at the Pacific whalers as “one of the heaviest blows we can strike at the enemy.” The Shenandoah, struggling with an acute crew shortage (her original British crew mostly declined to remain on the ship as Confederate sailors) impressed American crewmen from ships they captured while en route to the Pacific to hunt for whalers—although they captured their first whaler, the Edward, in the Atlantic, on December 4, 1864.

CSS Shenandoah

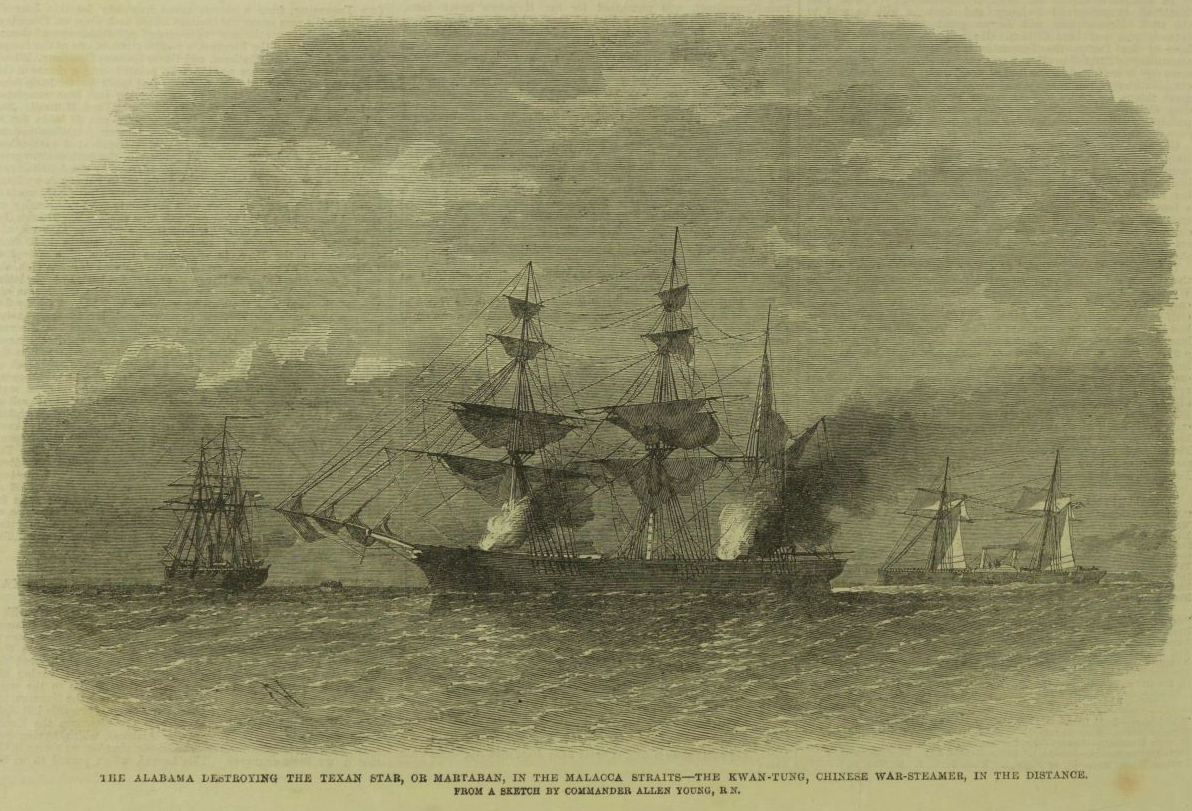

Meanwhile, the Alabama, after bagging more prizes off the coast of Brazil, sailed for the Cape of Good Hope. Disappointed with the lack of prizes there, Semmes pressed all the way to the Indian Ocean by September 1863 in search of prey, but found the pickings relatively sparse. In a way, as he was proud to note, Semmes was a victim of his own success: according to a speech at the beginning of 1864 by the English President of the Board of Trade, Northern trade with England had declined by upwards of 45 percent. While trade from American ships had declined, trade from English ships had increased, signaling a rise in vessels switching to British flags due of apprehension of Semmes and other commerce-raiders. “We did even greater damage to the enemy’s trade with other powers,” Semmes boasted, saying that the Alabama and her fellow commerce raiders had “broke up almost entirely…trade with Brazil and the other South American states, greatly crippled his Pacific trade, and as for his East India trade, it is only necessary to refer the reader to the spectacle presented at Singapore to show him what became of that.”

Alabama takes a prize in the Far East

The “spectacle presented at Singapore” was the sight of 22 American trading vessels that were laid up, presumably because word of Semmes had preceded his arrival. The sight of the disused American vessels at Singapore and other ports convinced Semmes to return to the Atlantic, “where the enemy still had some commerce left.” Semmes was doubtless pleased to find how effective his efforts had been, but he was also discouraged by the news from home, as “[t]he last batch of newspapers captured were full of disasters.” The Alabama, “like the wearied foxhound, limping back after a long chase,” was in need of repair as well. Semmes headed for Cherbourg, France, and his last blaze of glory.

We’ll discuss the fate of the Shenandoah, the Alabama, and the latecomer Tallahassee, (plus a Confederate ironclad you’ve never heard of) in our next installment, before finishing the series with a look at the Confederacy’s theory of commerce raiding and how things played out in reality.

Comments

...FLORIDA inspired one more round of controversy when Clive Cussler and his NUMA Foundation found her wreck and the USN proceeded to give him no end of trouble. Quite a few artifacts made it to the Hampton Roads Naval Museum, where their IDs made no mention of Cussler...who raised merry hell about it. Eventually the tags were - in extremely poor grace - changed to show a bit of print in almost microscopic size saying, 'Recovered by Clive Cussler'. Once he passed, the Navy wasted no time changing the ID tags back again.

And if you get a chance, read LAST FLAG DOWN, about SHENANDOAH's raiding career. The story has always been that they simply didn't know the war was over until she ran across a British vessel on 3 Aug 1865 - but there's pretty solid evidence they knew of solid, reputable reports of the Confederate surrender in mid-June...and chose to ignore it on pretty flimsy grounds.

Mike Kozlowski:

Things like that are why privateers were banned.

I'm curious how they were selling their prizes at this stage of the war. (Were they able to, and actually get the money back home?)

I'm not entirely sure, but I think they were just going for destruction and disruption at this point. The Union's diplomatic attacks on the CSA were pretty successful, so I don't think anyone was hosting prizes, and there was little chance of getting them home.

You Americans have probably worked through this to the 5th decimal place, so I don't need to do the research myself:

Was there any realistic chance that the Confederates could win the US Civil war? Or were they just hoping for something like Vietnam where the other side isn't motivated to keep making the sacrifices required to keep fighting?

And was there any realistic chance of that?

In short, and in order - No, Yes, and Yes.

The odds of an outright win for the CSA were basically NO - there was never any realistic chance of the Army of Northern Virginia destroying the Army of the Potomac and marching into Washington, D.C., to force terms on the US government. Even their greatest victories on the battlefield never came close to being the sort of knockout punch that would leave the Union unable to continue the fight - in fact, one of the major criticisms of Robert E. Lee is that he kept trying to end the war in an afternoon long past the point where the experience of his own army should have shown him that the war wasn't going to be won that way (by either side), and so he repeatedly exposed his forces to disproportionate losses seeking an unobtainable goal.

The morale issue was a real threat, though. Lots of people in the North didn't particularly want to be fighting a war, and as late as the autumn of 1864 (just about 6 months before the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse!) there was real concern that political shifts might result in the USA offering the CSA terms - even though by then the South was decidedly on the back foot, in every theater.

I'd also add that back then the US wasn't among the Great Powers. If one of (France or Britain) had joined the war on the South's side and the other stayed neutral, the chance of a negotiated peace would have increased dramatically. IIRC, Washington City being burned down by the Royal Navy was still in living memory at the time.

Of course, conceivable doesn't mean likely.

Given how hotheaded the south was were they even capable of not trying to inflict a knockout blow they couldn't possibly deliver?

Probably need a leadership capable of not firing on Fort Sumter which they didn't have.

AlexT:

Direct involvement would be a hard sell to the public especially given what the south was fighting for.

Direct involvement would be a hard sell to the public especially given what the south was fighting for.

You don't tell the French public you're going in there to support the slave states. You talk about Liberté, égalité, fraternité and/or the historical french ties with the people of the Mississippi and/or getting to stymie Anglo expansionism.

Even if France and England are out. And it's too early for Germany (though only just). What about Russia? Spain? Austria? Turkey????

@Doctorpat: Nobody but England and France really had the maritime power projection capability to intervene decisively in that era.

That said, England and/or France intervening was not a wholly implausible outcome, and it probably weighed heavily in the Confederate leadership's mind because they definitely weren't planning for a long war at the outset.

Morally, the English and French would not have wanted to side with slaveowners. Economically, they needed cotton badly, and the South was the largest exporter (though not for long; India and Egypt were ramping up rapidly). Geopolitically, the United States was an up-and-coming rival to England and France in the maritime empire-building game in a way the Confederacy would never be. And probably overriding all of that, war is bloody expensive and neither Britain nor France wanted to be part of that.

It almost happened anyway, by way of the "Trent Affair". An overeager US Navy captain stopped the Royal Mail Ship "Trent" on the high seas, and forcibly carried off two Confederate diplomats who had been traveling to England. Which is to say, precisely the thing the US had used as an excuse for war forty years earlier. If the matter had been left to public sentiment, it very likely would have resulted in war, and the British government did begin making preparations for same when cooler diplomatic heads on both sides ultimately prevailed.

If you're looking for an alternate history where the Confederacy wins, and you don't want to invoke time-traveling gunrunners, something like that is probably the best bet.

Doctorpat:

No, but that's what they'll think.

Doctorpat:

Was very pro-US in that time and probably the least likely great power to want to help the south.

Doctorpat:

You really think they'd help a government that announced they wanted their colonies in the Caribbean?