While reading Norman Friedman's British Carrier Aviation, I stumbled across a gem of a story that perfectly illustrated how important organizational structure can be to the design of things (in this case ships) in the physical world. More specifically, how the British decision to consolidate all of their aviation assets into the Royal Air Force in 1918 handicapped their carrier aviation two decades later.

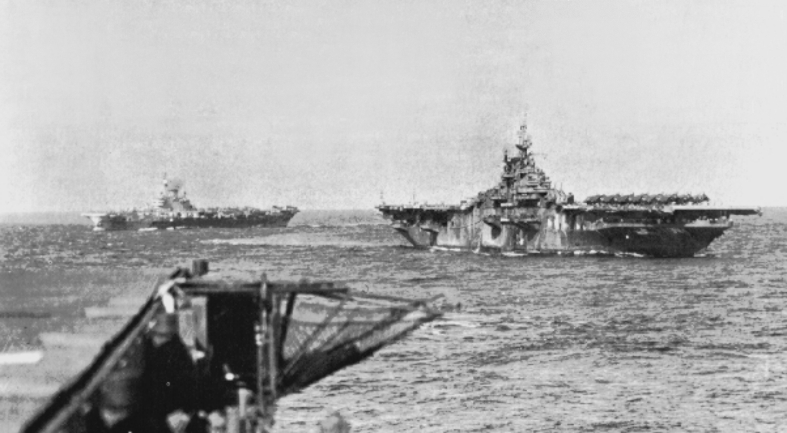

USS Randolph and HMS Indefatigable together off Japan

The fact that naval aviation was under the control of the RAF posed two problems. The first, which I've discussed previously, is that the RAF focused primarily on the direct use of airpower, starving the naval aviation community of funding and leaving the RN with a small force of rather bad planes when war broke out. The second problem was more subtle. Even the naval aviation forces that did exist reported up to the RAF, which meant that they had an outsize voice in carrier design and operation. And while this was undoubtedly nice for the pilots, it turned out that what was good for the pilots wasn't necessarily what was best in wartime.

The interwar USN and RN operated their carriers in radically different ways. The USN favored getting as many planes as possible onto each carrier, keeping most of the air wing in a "deck park" instead of stowing it down in the hangar. When recovering aircraft, each would trap aboard, then be moved forward of a crash barrier designed to protect the aircraft on deck if anyone missed a wire. This was a rather dangerous system for all involved, but it allowed a recovery cycle of 30 seconds or so. British practice was to keep the deck clear, striking each plane down to the hangar before recovering the next one, a process that took 5 minutes or so in the mid-20s but meant that a pilot who missed a wire could just take off and go around again. Pilots obviously preferred this system, and the air wing aboard Langley protested when then-Captain Joseph Reeves initiated the faster system in 1926, taking the air wing from a dozen or so to around 40.1 No British captain could make similar demands of his pilots, although efforts were made to bring down the strikedown interval. Besides the fact that they could complain to their bosses, there was also the fact that unlike an American carrier captain, who had to have some sort of aviation qualification,2 the British captain had no particular expertise in aviation and generally had to take the advice of his pilots.

Saratoga lands planes with a deck park forward early in her career

The result was very different cultures around naval air operations, with different results. American naval aviation was risky, but worked extremely well. American pilots were expected to push to the limit, be that in landing intervals or in terms of range, and the loss of some aircraft was expected, and would be made up for when more were procured. The British, on the other hand, expected that losses would be low,3 which meant shorter ranges and smaller air wings. For instance, the very-long-range strike during the Battle of the Philippine Sea was considered normal, and it was Mitscher's decision to turn the lights on that is remarkable, with the resulting losses generally being accepted as the cost of doing business.

HMS Victorious showing her forward round-down and streamlined island

This even got to the point of affecting the design of the carriers themselves. A British carrier of the prewar era is clearly designed to be as nice to operate from as possible. There are substantial round-downs fore and aft to reduce turbulence over the deck, and the superstructure is often airfoil-shaped to ease the air's passage. The deck is carefully kept clear otherwise, with the guns often integrated into the edge of the deck. An American carrier, in contrast, is basically a hull with a deck on it. The fore and aft round-downs take up valuable length that could otherwise make the deck park bigger, so there's no sign of them, and the superstructure is boxy and has guns mounted around it.4

A deck park on Implacable, late in the war

This also ties into the British decision to build armored-hangar carriers, which remains controversial to this day. If planes are rare and precious, then it makes sense to try and keep them as safe as possible, particularly if there are limits on how many you can operate from each carrier.5 Of course, there were other factors at play. Faster aircraft meant that scrambling fighters on the basis of seeing enemy bombers approach was no longer viable, and radar didn't exist yet, so the British believed that the best option was to use the fleet's AA guns and armor up to protect against any leakers.6 And when the 1936 London Treaty removed any caps on carrier numbers, they apparently decided to make the most of their limited force of aircraft by dispersing them among as many safe baskets as possible.

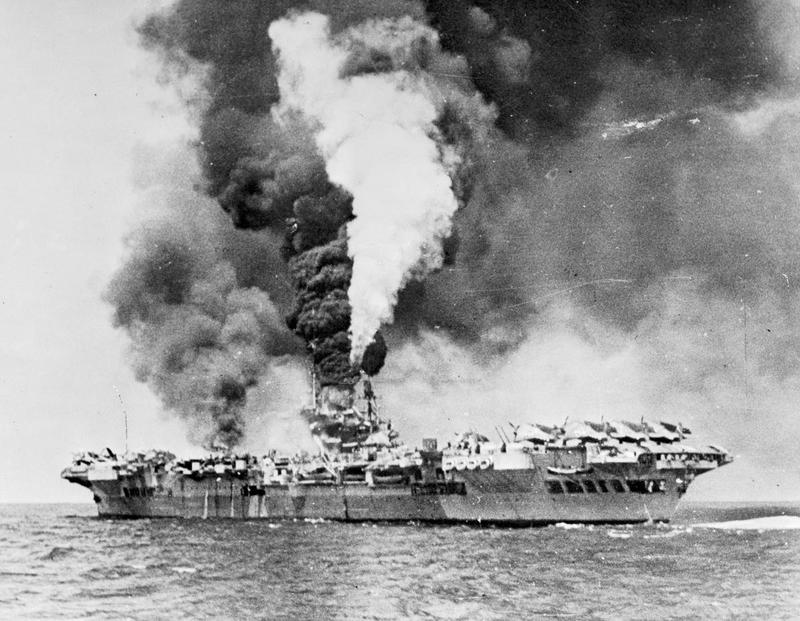

Formidable after a kamikaze hit

In practice, this worked out poorly. All of the weight spent on armor meant that they had quite small air wings, and with the arrival of radar, the air wing became a powerful defense as well as the carrier's offense. More broadly, the war vindicated the USN's operational concepts, and by 1945, the British were operating their carriers in the American manner, but handicapped by their relatively small decks. And while the resistance of the British carriers to kamikaze damage off Okinawa is well-known,7 it's worth pointing out that the much larger American force suffered approximately the same number of hits on its carriers as did the small British group. Better to avoid taking a hit in the first place than to deal with it by "sweepers, man your brooms".

1 There are two reasons this system allows a bigger air wing. First, there's the obvious answer that you can park planes on the flight deck as well as in the hangar. Possibly more important is the drop in recovery time, because the faster you can recover planes, the more you can get aboard before they start running out of fuel. For instance, if the typical reserve is 20 minutes, a carrier using the USN method can get 41 planes landed, while a British-style carrier can only land 5. ⇑

2 This didn't necessarily mean he had to be a pilot. Reeves was qualified as an aviation observer, and it was only during WWII that senior officers had begun to come up through the piloting ranks. ⇑

3 Worth noting that this probably also played into the distaste for deck parks. Leaving planes on deck isn't great for them, particularly if you're somewhere like the North Atlantic, and if you assume that you can't replace them because the RAF would rather spend its cash on bombers... ⇑

4 In partial fairness to the British, some of this probably dates back to the fact that they started carrier aviation during WWI, when planes were very light and vulnerable to turbulence, while the USN waited until the early 20s, when planes were significantly heavier. Yes, this probably does tie into why the angled deck took so long to happen. ⇑

5 As a counterpoint to this, Ark Royal, the last carrier before the hangars were armored, had a much larger air wing than the later armored deck carriers. ⇑

6 This is often ascribed to the need to operate in the waters around Europe, which oversimplifies things considerably. The RN had global responsibilities, and even in the mid-30s, Japan was seen as the primary enemy. ⇑

7 Also overstated, but that's an issue for another time. ⇑

Comments

To take a quick look at the other powers: carrier construction in France and Germany was plausibly held back by similar organizational issues, but in Italy it appears to have been opposition from within the navy, and in the Soviet Union from Stalin.

At the other extreme, Japan not only didn't have a separate air force (the US also didn't, the rest all did), but split its land-based strategic bombers between the navy and the army.

Langely instead of Langley.

(and if anyone else is wondering whether the modern British choice of STOVL carriers is also a safety thing: probably not, it seems that STOVL operation is if anything more dangerous than CATOBAR.)

@muddywaters

In Italy the opposition to fixed wing naval aviation was from the Regia Aeronautica, then from the Aeronautica Militare, and it lasted upto the '80s.

muddywaters:

Because the Harrier needs fly by wire but doesn't have it (except for a handful of experiments).

The F-35B may end up with a very different record.

The British adopted STOVL because they didn't think they could afford CATOBAR and had this cool new STOVL fighter they'd built. They kept it for weird psychological reasons, even though they'd have been better off with CATOBAR on the QEs.

Methinks that if they had asked on the southern side of NATO: "Ehi mates, sorry for Taranto, do you want to build a few CATOBAR carriers with us to lower the general costs?" then the QE class and Cavour would have been quite different.

Multinational defense projects are hard to do, and Italy in particular has very different priorities than Britain does. The nation with the closest requirements to Britain would have been France, but the French are generally regarded as the worst to work with.

A couple of thoughts. First despite the advantages of the armored deck in terms of damage resistance it does come with tradeoffs. As you note the brits even when they went to American style Deck Parks never operated air groups the same size of the American Carriers. Which seriously limited both the defensive power of the carrier and its offensive power. Both of which make the carrier more vulnerable and more likely to be knocked out of action or sunk. Also the deck only protects against 1 threat bombs. It does nothing for torpedoes. I would even argue it hurts you against the torpedo threat because of less stability with the weight up high and less defensive fire power to stop the torpedo carrying aircraft. And when you look at American Fleet Carrier losses in WW2 what do you find? Lexington (Torpedo hit leading to AvGas fire) Yorktown (Torpedo hits leave her dead in the water) Hornet (Torpedo hits) Wasp (Torpedo) and that's it. The Americans don't lose a single fleet carrier to the results of being hit by bombs or Kamikaze. Though I will admit Yorktown being hit by bombs and going dead in the water is a more nuanced case but there are other elements at play in her loss.

Second the RN massively screwed up the QE class carriers. Not having a CATOBAR carrier means little to no effective AEW a vulnerability that should have been burned permanently into their thinking by the Falklands war. So, what they have are two massive and expensive ships (they are roughly the same size as the now retired Forrestal class supercarriers) with a single squadron of VSTOL fighters (limiting their capabilities) and helo based AEW that is very limited when compared to something like an E-2D. Yes the space is there to deploy them with more than one squadron of F-35s but there is no workaround for the lack of effective AEW. Its just idiotic.

It's somewhat more even if you count everyone's: 10 total (5 fleet) carriers lost to bombing, 3 (0) to kamikazes, 8 (5) to air-dropped torpedoes, 18 (8) to submarine torpedoes, 2 (1) to guns, and 1 (0) to accidental explosion.

I don't know how many of those were small enough bombs that armor would have helped. Or how many were seen in time that having more/better fighters would have helped. (Though a big air wing is also useful offensively: the enemy can't attack you if you sink them first.)

The British (and possibly everyone) also greatly over-estimated the effectiveness of AA gunfire: 1931 estimate 1 kill per 184 4" shots with HACS control, early-war actual 1 per 2000-10000. (The USN Mk37 was better, but not that good.)

Based on pictures I've seen, Interwar and WW2 deck parking seems to happen mostly at the front or back of the runway, significantly cutting into runway length. Especially in pics like the Saratoga pic you used here, where something like 2/3 of the deck is covered in planes.

So in order to use deck parking, you need a flight deck that's quite a bit longer than you really need for the actual takeoff and landing. So a carrier designed with deck parking in mind seems like it should be longer than a carrier designed with British-style operations in mind. I suppose below-deck hangar space might be another driver of ship length, but as you note the British carriers also have smaller air wings.

Skimming numbers on wikipedia, American carriers do seem to be a little longer on average than similar-build-year British carriers, but by less than I would have expected from this, and there seems to be a fair amount of overlap. What was driving the length of the carriers to be about the same for both countries?

I really should write up a complete explanation of carrier ops, because the British didn't put planes up on deck one at a time for launch. They and the Americans in fact launched pretty much the same way. All of the planes for the strike would be ranged aft on deck, with the size of a strike set by the required runway to take off (so a longer carrier could do a bigger strike, as could one that didn't have the round-down). The engines would be warmed up (important to avoid the thing that lets you fly suddenly stopping, and while the Americans could theoretically do it in the hangar, the British couldn't because of design details I didn't get into here) and the first planes would take off down the deck. This was before catapults were needed, and doing it this way allowed a shorter takeoff interval, too. Typically, the order would be fighters, then dive bombers, then torpedo bombers, which was not coincidentally the ordering of the amount of deck the types took to take off.

The carriers were of similar displacement, which tends to push you into a reasonably narrow band of lengths for structural and hydrodynamic reasons. Also, you wanted a long deck for reasons described above, even if you were British and using your carriers wrong.

Funny thing that. Launching the fighters first puts the planes with the shortest endurance in the air the longest.

Ahh tradeoffs.

Well, the French are probably still smoldering for the FREMM Fiasco.

There was an understanding that if one of the FREMM nations sold one, the other would get a percentage of the profit.

The French sold one to Egypt, and we got zilch, so the understanding collapsed.

Then WE started selling them like hotcakes...

Frode

What is stopping them from recovering the fighters first?

@Frode

The tradeoff involves having fewer airplanes in the strike. And it launches planes really fast, so the endurance hit probably isn't as great as you might think.

Thank you for this article Bean. Quite a coincidence as Friedman's British Carrier Aviation was next on my reading list. It was recommended to me a couple of months ago and took up the suggestion.