Coastal defenses have a long history in the United States, with Charlesfort, the earliest example, located at Parris Island, South Carolina,1 and dating back over two centuries before the country won its independence from Britain. It, like most other early coastal fortifications, was a simple construction of a few guns protected by earth and timber walls. During the pre-revolutionary years, the sea was the best way of moving between isolated settlements, and most major communities built such batteries in times of crisis, abandoning them to the elements after the threat had passed.

Fort Independence, Castle Island, Massachusetts2

A few prominent sites had more permanent fortifications built, most notably Castle Island, ideally positioned to cover the main shipping channel into Boston. The first fortifications were built there in 1634, and expanded as Boston grew in importance, being rebuilt first in wood and then in stone. In 1692, it was rebuilt once more and named Castle William, while an expansion in 1701 saw it grow to over 100 guns, the largest fortification in British North America. It formed an important stronghold for the British in Boston as the inhabitants of that town grew increasingly restless, and was destroyed when they evacuated Boston after George Washington emplaced anti-ship batteries of his own to dominate Boston Harbor.

Fort Mifflin

Coastal defenses naturally multiplied during the following years of war, most built on the standard pattern of using whatever cannon were to hand in a hastily improvised earth-and-timber battery. Bigger cities gained more elaborate defenses, with both New York and Philadelphia siting forts to cover rows of underwater obstacles positioned to block the main shipping channels. These proved effective so long as the forts held out, although Fort Washington and Fort Lee, which guarded the Hudson River, fell to attack from landward when the British took the city in 1776. The next year, they were able to occupy Philadelphia unopposed, but found the Delaware River below the city blocked by forts still in American hands. Fort Mercer and Fort Mifflin held out for a month and a half after the city fell, despite heavy attacks by both land and sea, even destroying several British ships that ran aground near them. Eventually, they were forced to evacuate, but not before significantly delaying further action by the British and buying the Americans much-needed time.

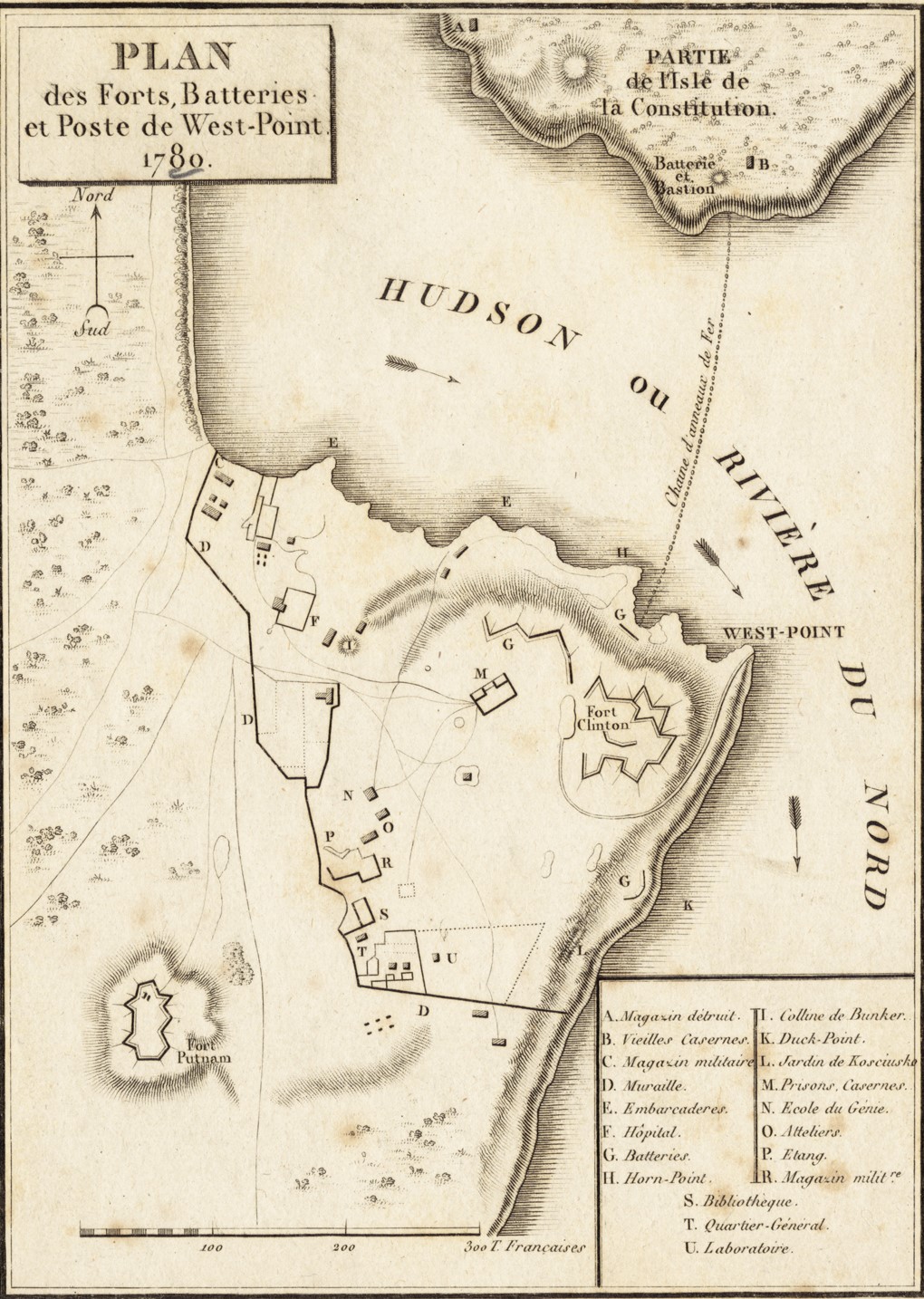

The fortifications at West Point during the Revolutionary War

Even though New York City had fallen to the British, the Hudson River remained a vital strategic artery whose fall could sever the connection between New England and the rest of the colonies. Fortifications were therefore erected further up the river, first Fort Montgomery, which soon fell to the British, and then at West Point, where a giant chain made of 114-lb links was stretched 600 yards across the river, supported by rafts of logs and covered by numerous fortifications. The British never seriously attacked the site, although they did conspire with Benedict Arnold to seize it before his plot was exposed.

Surviving links of the Great Chain at West Point

After the war ended in 1783, there was little interest in the maintenance of coastal fortifications by either federal or state governments, and most fell into disrepair. A decade later, revolution broke out in France, and the US, afraid of being drawn into the conflict, responded by building both frigates and coastal defenses. The frigates are out of scope here, but the fortifications, built largely by hired French engineers, became known as the First System of US coastal fortifications. There was little high-level coordination, but most of the forts were of earth, timber, and occasionally stone, and done in the bastion style that allowed the guns of the fort to cover all of its outer walls. Two examples survive today, Fort Mifflin, rebuilt after the Revolutionary War, and Fort McHenry, famous for standing off a 25-hour British bombardment during the War of 1812, which inspired the writing of The Star-Spangled Banner.

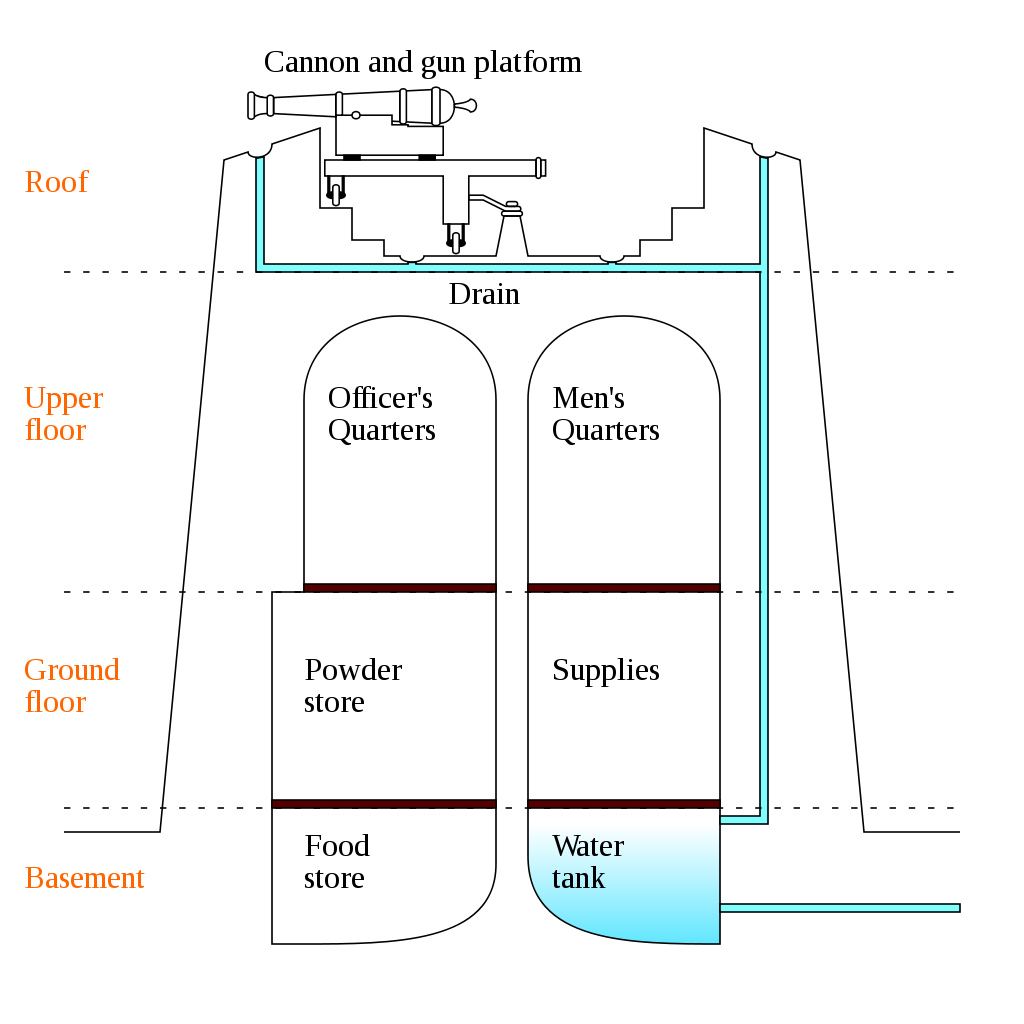

A Martello Tower

After 1800, with the resolution of tensions between the US and France, interest in continuing the First System waned. Work continued at a few sites, but it wasn't until the later part of the decade that events in Europe rekindled interest in fortifications in the United States. In the meantime, the rise of Napoleon lead the British to invest in coastal defenses of their own, with a major program starting around 1805. The most prominent results were the Martello towers, a series of over 100 small masonry towers, each crowned with a single cannon and intended to serve as strongpoints in case of a French invasion. Around more critical strategic points, existing fortifications were upgraded and new ones constructed, such as Eastbourne Redoubt, an 11-gun round fortification intended to anchor the Martello Tower line. The most prominent new fortifications were on the western heights above Dover, intended to protect the vital port, the closest in England to the French coast.3

A model of Eastbourne Redoubt

In 1807, the British frigate Leopard attacked and boarded the American frigate Chesapeake, looking for deserters from the RN. The Americans were outraged, and began a new program of fortifying their harbors against foreign attack, known as the Second System. There were two major differences between this and the First System. First, it was largely conducted by American engineers, trained at the new military academy at West Point, founded in 1802. Second, it saw the introduction of a pair of advances in fortification design, the all-masonry fort and the casemate. Before this era, the vast majority of fortification guns were mounted "en barbette", firing over the top of the fortification. This set a hard limit on the amount of firepower that could be crammed into a length of wall. The obvious alternative was to mount guns in casemates inside the wall, which could be stacked in multiple levels, much as in a contemporary ship of the line.4 The main drawback of all this was the difficulty of firing a heavy gun in an enclosed space, but improved design made it practical by the early 1800s. The result were a handful of fortifications like Castle Williams, erected to guard New York Harbor. Each of the four levels in the near-circular fortification mounted 26 guns, protected by sandstone walls 7 to 8' thick. Such advanced fortifications were built at only a handful of harbors, with the older earth-and-masonry forts making up the majority of the second system. Surviving examples include Fort Jay in New York, Fort Norfolk in Virginia, Castle Pinckney in South Carolina and Fort Wood, a star fort that ultimately formed the base for the Statue of Liberty.

Castle Williams

Most of the Second System forts were essentially complete by 1812, when tensions between the US and Britain finally spilled over into outright war. A cursory overview of the war reveals only three cases in which the British engaged any serious American coastal defenses. The first was at Craney Island, Virginia, which protected Hampton Roads from invasion. The second was their unsuccessful assault on Fort McHenry, immortalized in the National Anthem. The last, taking place after the peace treaty had already been signed, was the attempt to take Fort St. Philip, Louisiana. The Americans held out, and prevented the British from reinforcing the army attempting to take New Orleans, contributing to Andrew Jackson's victory there. Even more important than their actual victories was the strategic effect of the American fortifications. The only major city to fall to the British, Washington DC, was also one of the few that lacked such defenses. Places like New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Charleston were not even attacked, the British preferring to blockade from a safe distance.

Fort McHenry with outlying batteries intended to strength its defenses

After the end of the war, the US finally moved to put coastal defenses on a regular basis, with the initiation of what became known as the Third System. Unlike its predecessors, both emergency responses to international tensions, the Third System would continue for almost half a century. We'll pick up its story next time.

1 Yes, that Parris Island. ⇑

2 This is the third system fort built there later, which is now a park, with the fort itself open for tours during the summer. ⇑

3 Napoleon was concerned about British invasion, too, and built forts to protect against the possibility, including Fort Napoleon in modern Belgium. ⇑

4 The parallels between fortification terminology and warship terminology for gun mountings are obvious. ⇑

Comments

...Excellent article, and very glad to see Castle Pinckney get some love. A little background - according to the National Park Service they discourage people actually going out there, but there are apparently no actual 'off-limits' orders. I've spoken to people who have been out there and the word they keep using is 'amazing' but caution does need to be applied. The entire structure has been sinking, pretty much since it was built, and you definitely want to go at low tide. On the other hand, the structure is still mostly intact (albeit being reclaimed by nature) and at least two or three of the Columbiads that were mounted there are still in place, though they're sinking into the terrain as well.