During the first half of the 19th century, the US developed probably the most sophisticated and advanced system of coastal defenses in the world, a system which largely failed its test during the American Civil War. But coastal defenses were hardly limited to America, and the events of the Civil War were presaged by another war a decade earlier, on the other side of the world.1

Fort Alexander, a sea fort near Kronstadt

When Peter the Great established St. Petersburg in 1703, his intention was to give Russia an outlet to the rest of the world via the Baltic. Unfortunately, sea access works both ways, and one of his first actions was to set up fortifications on Kronstadt, 30 miles to the west of the city, to control the channels leading to his new capital. The Swedish, Russia's main enemy at the time, quickly began their own program of coastal defenses, composed not only of fortifications, most notably Sveaborg outside of modern-day Helsinki, but also a dedicated "archipelago fleet" of galleys and other coastal vessels under separate command from the main navy. After several wars throughout the 18th century, Russia finally took Finland in 1808, capturing Sveaborg after a short siege from the landward side. By this point, in a mental leap peculiar to Russia, the existing defenses of Kronstadt, despite being modernized to keep pace with changing technology, needed forward defenses to protect them, turning the entire Gulf of Finland into a Russian lake.

Fortifications at Sveaborg

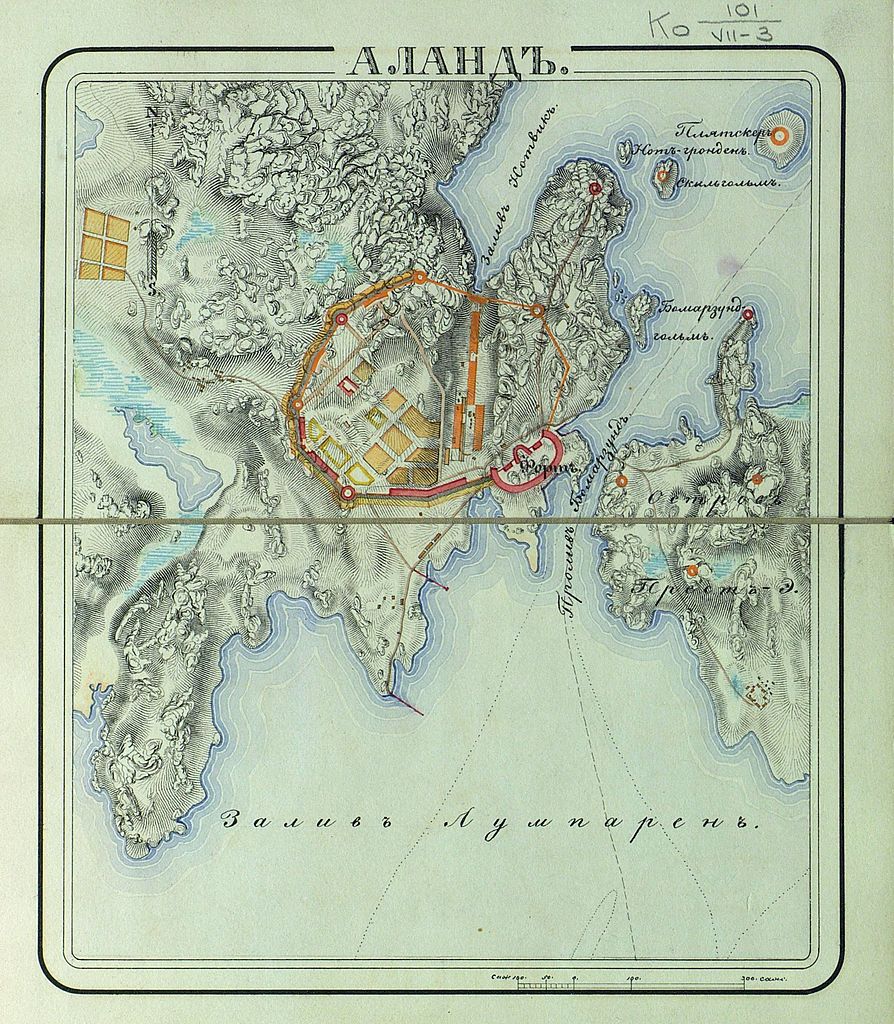

The linchpin of this would be a new base at Bomarsund, in the Aland Islands. A major fortification would protect a harbor for the Baltic Fleet, as well as providing a base for the galleys and other small vessels that were the standard tool for warfare in the islands and shallows of the Baltic. Even more importantly, Bomarsund was far enough west to avoid the worst freezes in the Gulf of Finland, which blocked in the other bases for the Russian Baltic fleet for much of the year. Work began in 1832, and continued for the next two decades. By 1854, when Russia went to war with Britain and France, the main fortification, which resembled the two-tiered forts of the Third System in the US, was complete, along with a few outlying towers. However, there was still a great deal of the original plan to be executed, and Bomarsund would be the first target of the fleet the British would inevitably send to the Baltic.

A map of the area around Bomarsund. Only the central fort (red circle) and some of the outlying towers were completed in time for the war

The war in question was famously incomprehensible, fought primarily on the Crimean Peninsula which gave it its name. But while it is remembered for pointless butchery and a particularly stupid cavalry charge, the Crimean War laid many of the foundations for the following century of warfare, and was decided not in what is now Ukraine, but by the ability of the British to overcome Russian coastal defenses in the Baltic, and bring sea power to bear on the Russian capital. Even the threat of the RN appearing off St. Petersburg was enough to keep a quarter of a million of the best Russian troops in the north, well away from the Crimea. The British fleet sailed before war was declared, bringing with it over a dozen ships that, while superficially similar to the vessels that fought Napoleon, were equipped with steam engines and screw propulsion. They would prove decisive, particularly as the Russians had no such ships. Steam would prove a decisive advantage over sail in its first major test in combat.

A CG image of the fort at Bomarsund

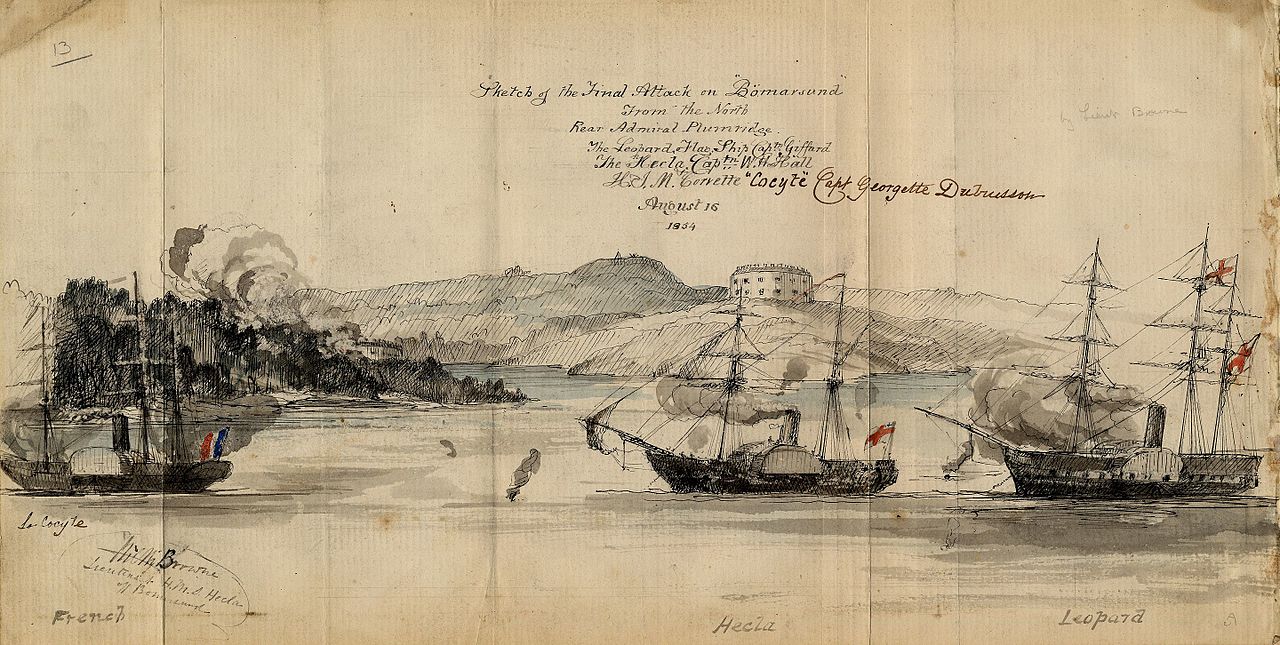

The first actual clash between Russian defenses and British ships came in June 1854, when a Captain Hall led a small force of paddle steamers against Bomarsund, bombarding it for several hours. Unfortunately, he was able to do only minimal damage, and the action is notable primarily for the actions of Charles Lucas who threw a shell over the side of HMS Hecla before its fuze could detonate. He would later be the first recipient of the Victoria Cross. Even before Hall's attack, the British had sent a pair of steamers under Bartholomew Sulivan to chart the waters of the Aland Islands, and he had discovered a passage into the sound south of the fort. The Russians had been told that it was too shallow for ships of the line, and as a result had dismantled a battery intended to cover it. This was a fatal mistake, and in August, the British, having reconnoitered Kronstadt and Sveaborg and found them too strong to attack directly, instead took a force of ships through this passage. The Russians were unable to respond, primarily due to their lack of steamers, which allowed the British to act much faster than their enemies could.

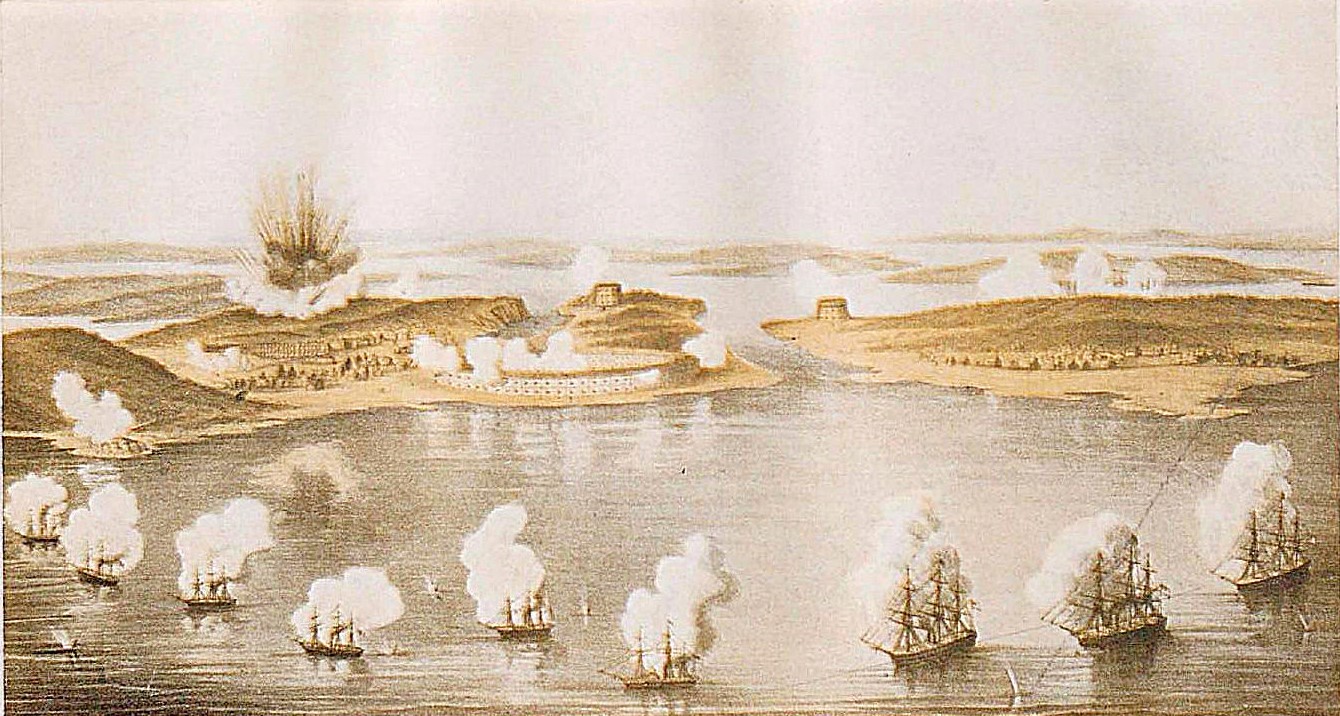

British ships bombard Bomarsund

On August 8th, French troops, accompanied by British sailors and Marines, went ashore near Bomarsund. The lack of outlying defenses meant that the the fort was indefensible from land, and within a week, the outlying towers were reduced by artillery and infantry attack. The assault was also witnessed by a number of private yachts that had accompanied the fleet, some of which took the war as license to prey on the local population. On the 15th, the ships began a bombardment of the main fort from an angle that only a few guns covered, and the fortress began to crumble. As it became obvious that the Allies planned to reduce it with artillery alone, morale crumbled, too, and the Russians surrendered the next day. The fort was demolished, except for some casemates used for trials, which demonstrated that the stone fortification was still quite resistant to naval ordnance.

The final attack on Bomarsund

There was considerable debate over what to do next, with orders going out for an assault of Sveaborg in the wake of the British landings in the Crimea in September, but these were cancelled as that campaign turned into a slow, bloody stalemate, and the Baltic Fleet would withdraw for the winter. The force in the Black Sea had no such option, and in October, the Anglo-French fleet was tasked with supporting a major attack on the defenses of Sevastopol. The attack was called off due to the destruction of the French magazine ashore, but the bombardment went on anyway. The Russian positions took little damage, primarily due to the Allied reluctance to close the range, while the ships suffered only slightly more, with only two ships not fit for action the next day, and a handful of casualties.

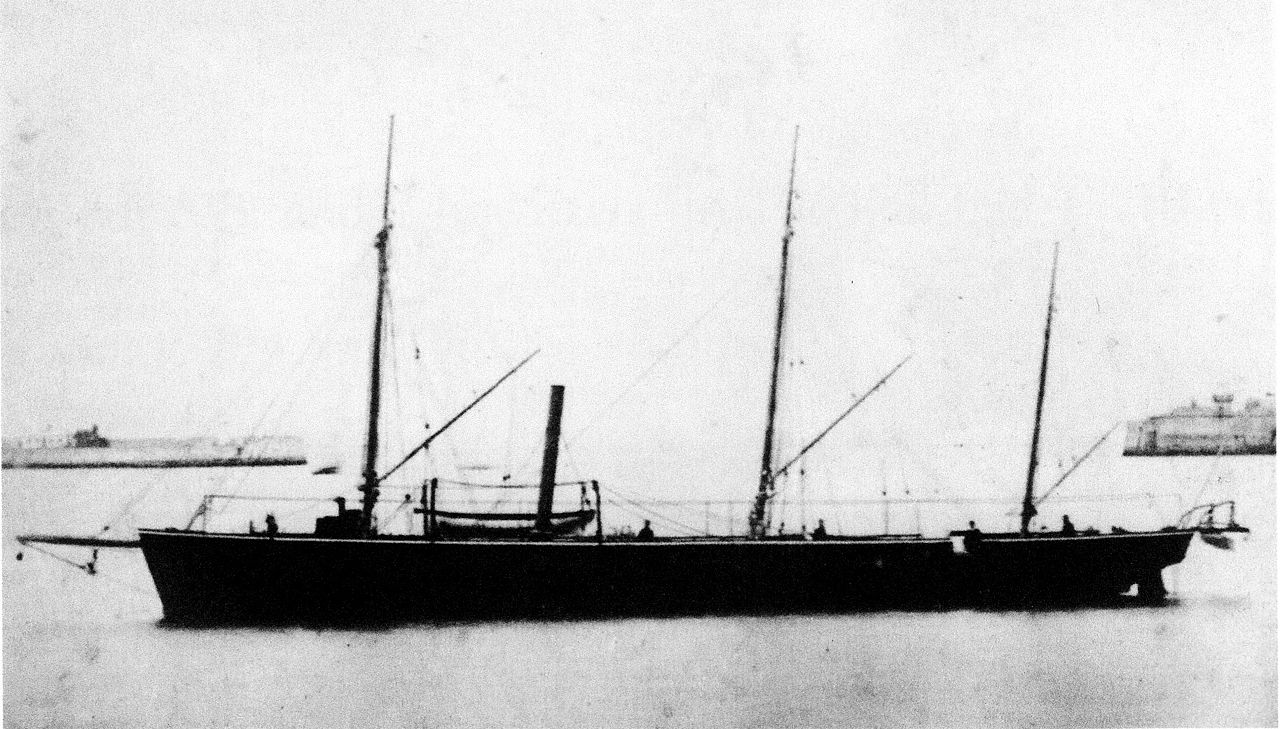

Crimean-era gunboat Raven

It was quickly recognized that the existing fleet was not particularly suitable for attacking coastal targets, and a crash program of gunboat construction was started, with an emphasis on shallow draft and the use of a few heavy guns for attacking shore targets. 26 were ordered in 1854, and over 100 more the next year. The program was successful in delivering the vessels, although the unprecedented demands for labor caused rampant inflation along the Thames and did a great deal to kill off the shipbuilding industry in that area. The gunboats were joined by a large flotilla of mortar vessels, each armed with a single 13" mortar fixed at a 45° angle and aimed by varying the charge. These were built strongly to take the force of the mortar, but lacked steam engines and were usually towed into position.

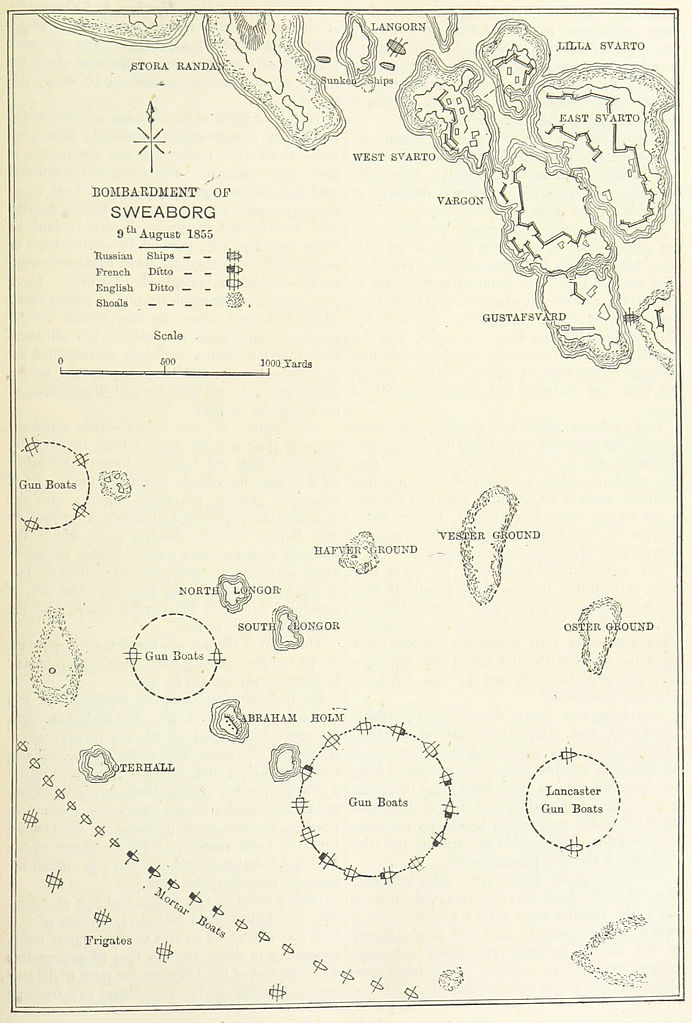

The Allied attack on Sveaborg

The Russians had spent the winter of 1854-1855 strengthening their defenses in the Baltic, and the fruits of the British expansion program2 didn't start to arrive until relatively late in the year. As a result, most of the summer was spent raiding the Finnish coast, and the British encountered naval mines for the first time. In August, the combined fleet finally went after Sveaborg, mortar vessels bombarding the dockyard facilities there for almost 48 hours, supported by gunboats and rocket fire from ship's boats. No direct attempt was made to attack the coastal defenses, which proved ineffective in attacking the British a mile and a half offshore. The bombardment was effective, extensively damaging the dockyards and setting off several magazines, and was only called off when the mortars of the bombarding force were worn out and cracking. Unfortunately, this success couldn't be followed up as the weather closed in.

The ironclad batteries in action at Kinburn

This was also the era when the explosive shell was introduced, and Napoleon III of France came up with the idea of armoring a ship with iron to protect against it. His initial plan was to fit ships with racks of cannonballs, but tests showed that solid plate was much more effective. Napoleon III wanted ten floating batteries armored in such a manner, but French industry could only build five in time for the 1855 campaign, so the other five were built by the British. These were intended primarily for inshore work, with relatively shallow drafts, 14-16 heavy guns each, a speed of maybe 4 kts and 4" armor. Only the French ships reached the Black Sea in time to see action, when they attacked the Russian fort at Kinburn, which protected the mouth of the Dnieper River. Three of the floating batteries were dispatched, along with 10 ships of the line, 17 frigates, and a flotilla of gunboats and mortar vessels. After several days of waiting for the seas to calm enough for accurate gunnery, an intense bombardment was launched, with the ironclads standing in to duel the 80-gun masonry fort. After four and a half hours, the Russians surrendered, although the extent of damage to the fort and its garrison remains unclear.3 Despite a total of over 200 hits to the ironclads, the Allies suffered only two dead and two dozen wounded. It was the first battle in which ironclads participated, and laid the groundwork for what was to follow.

An 1855 map of Kronstadt

While all of this was going on, Sullivan, who had scouted Bomarsund, had come up with a plan to attack Kronstadt. The southern forts were still viewed as impregnable, but he believed he could plant charges on the obstacles that blocked the channel to the north, allowing the armored batteries to pass through and duel with the lighter guns defending that side of the island. This would open the way for the mortar vessels, which would destroy the Russian fleet and its base facilities, and threaten St. Petersburg directly. It was a good plan, and when it was leaked to the Russians, they realized that the 1856 campaign would be focused not on the remote Crimea but on the doorstep of the Russian autocracy. Peace negotiations proceeded rapidly, and the plans never had to be implemented. The Russian coastal defenses had failed, and in doing so, had undermined the entire war effort.

British ships attack the Taku Forts in China

The second half of the 19th century would see a number of actions between ships and coastal defenses, ranging from the massive Bombardment of Alexandria to smaller actions like the attempts to capture the Taku Forts during the Opium Wars in China and Western bombardments of Japan to enforce their treaty rights. More numerous still were actions between single gunboats and small numbers of guns ashore, which took place throughout the empires European powers were busy putting together. But these were fought against defenses that had been rendered obsolete by improvements in guns and gunnery, and the major powers were quick to put these advances into use in their own defenses. We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 Another battle which took place even earlier was at Eckernforde, when German coastal defenses destroyed a Danish warship. ⇑

2 The French also participated, but my sources on this campaign are incomplete and focused almost exclusively on the British. ⇑

3 D.K. Brown suggests that the lessons of this engagement and Bomarsund, as well as various actions during the American Civil War, is that the morale effects of fire from the fleet were often enough to induce relatively undamaged forts to surrender. He also cites the bombardment of Algiers in 1816 and the bombardment of Acre in 1840. ⇑

Comments

Nit: The first test of steam vs. sail in combat had been seven years earlier, off Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico. Steam didn't win. Don't Mess With Texas.

I'm wondering about the mechanism by which Bomarsund guarded the Gulf of Finland.

A look at a map makes pretty clear it isn't directly covering the passage with its guns, nor guarding any sort of chain or physical obstacle—the only thing it directly protects is its own harbor. ACOUP covered how a land fortress can indirectly block access by providing a safe retreat for mobile forces, but it's not clear to me how well this generalizes to the sea.

Was the British fleet relying on (or at least benefitting from) shipments that could have been interdicted had they bypassed Bomarsund? Did fleets at the time deploy with a 'front' and 'back' such that an attack from behind would be a problem? Or was there some other reason a fleet behind yours would be worse than a fleet in front?

@John

That was an extremely minor skirmish somewhere nobody cared about. This is the first and second ranked navies going up against someone in the top 5.

@ADA

It's not too dissimilar from what ACOUP describes. Yes, a fleet doesn't have quite the same sort of supply lines that an army does, but you probably don't want to sail into the Gulf of Finland with an enemy fleet at your back. You'll likely have to fight your way past them to get out again, as opposed to having a chance to avoid action. In this case, they're also going to use it as a base for light units, which will be less than fun to deal with.

I think this should be 18th century, right?

I can see a cycle of 'seize buffer territory > fortify it > develop and integrate it into your empire' repeating as each new buffer region in turn becomes sovereign ground that must be protected. I can't immediately think of any other examples of this (the closest I can come to is the US with the Philippines, which is somewhat different) but it doesn't sound like completely bizarre behaviour on the part of the Russians.

@Alexander

It's definitely not a cycle unique to the russians. You go back to the late 1800s, and all the american navalists can talk about is how without a panama canal, the US is doomed, but with it all problems would be solved. Then the minute the canal is finished they start noticing all these threats to the canal! The security dilemma is enteral.

@Alexander, @Cassander, Isn't that the story of how the British Raj, and before that the Roman Empire, was created.

Have a border dispute. Things go back and forth a few times until you conquer this troublesome neighbour to ensure your own safety. Then start having issues with the next country threatening your new territory.

The one minor change I can think of is that the British were likely to stick to the letter (if not spirit) of their actual agreements. So those small Indian states who resolutely ignored all the various provocations and insults to never, ever attack the British territory were able to avoid (largely) ever actually being conquered. Hence the ever expanding British directly controlled empire flowed around such states and left them as nominally independent countries within the British territory.

In the first sentence, "18th century" should be "19th century."

Ack. I seem to have century confusion on this one. Fixed.

From memory, Crimean War:

Russia attacks Turkey looking to expand.

Britain joins the war to limit Russian gains and keep them out of the Med.

Savoy joins the war to kiss up to the great powers.

France joins the war to ????. What on Earth was France trying to accomplish, again?

Beats me. Napoleon III was kind of weird.

(More seriously, France had long-time interests in the Balkans, and I think those were a big driver.)

France lost half a million men against the Russians, and then was invaded by Russia, one generation previously. They might have just wanted to put the boot in while they had a chance.

Obviously they were invaded and lost lots of men by the British TOO, but they were too dangerous to go up against.

If you got wrecked by a lion and a dog, you might seize a chance to kick the dog, even if you were still carefully being polite to the lion.

Napoleon III is a fascinating character I wish I knew more about. He's arguably most important actor in Europe between Metternich and Bismark, but I'm not aware of a good biography. He liked the UK wanted an alliance with them to get France out of the diplomatic dog house. Arguably that worked but honestly, I think it was driven more by his desire to be the center of attention than anything else.

This makes me wonder what the plan was if the defenders hadn't surrendered. In all these stories of naval forces "reducing" forts ashore, the deciding factor has been whether the defenders can hold out, psychologically. If the defenders don't panic and surrender, it seems like the fort can hold out indefinitely against naval forces, because the naval guns of the time weren't accurate or powerful enough to demolish the casemates that the fort's guns would be firing from.

In this case, it seems like the deciding factor was the fact that the Russians weren't ready for an extended siege, and so quickly surrendered once they realized that they were surrounded and under fire. But what would have happened if they hadn't?

In practical terms, the vast majority of battles are decided psychologically instead of by literally killing everyone on the other side. Note that the Allies did have troops ashore at Bomarsund, who could have stormed it, so it's not like they could have just held out until the artillery got bored. My source indicated that morale actually began to crumble when the thought of getting to do hand-to-hand fighting went away. Being killed without being able to respond is tremendously demoralizing.

@quanticle

If the defenders don’t panic and surrender, it seems like the fort can hold out indefinitely...

Well this IS what we saw time and time again. Leningrad and Stalingrad showed that you can pound the city to ruins, or even rubble, and if the defenders don't run out of bullets, and rats to eat, they will still be holding out.

On the other hand, c.f. Paris. Just give them a big scare and they might surrender right away.

One very important reason to treat your prisoners of war with decency. The French could surrender and know that they'll just be second class citizens in an occupied country. The Russians knew they'd be starved to death as slaves, and so they held out till the bitter end.

Thanks for the interesting series. About Bomarsund and the morale in the fortress, there's a Finnish folk song about the siege which touches on this issue. The song was apparently originally written by some of the garrison soldiers who spent 20 months in Lewes in very comfortable captivity after the surrender. According to the song, the soldiers became angry when the flag of surrender was raised and the gates were opened. Obviously, this is mostly bravado after the fact (and another line states that nothing could be done since thousands of French and English were storming the fort). This song was later adapted into a well-known patriotic song by expurging the parts about the surrender.