I've referenced HMS Dreadnought many times, as befits one of the most influential warships of the 20th century. However, I've never told the story of her origin in one place, bringing together the many threads of development that went into her design.

HMS Dreadnought

Dreadnought was in many ways the natural result of improvements in the technology of warships, most notably gunnery and propulsion. Gun ranges were increasing thanks to the work of men like Percy Scott, and the torpedo had become a major threat at close range. This greatly reduced the effectiveness of the 6" QF batteries of the pre-dreadnoughts. Longer ranges limited rate of fire to allow for spotting, and the steeply-falling 6" shells had much smaller danger spaces than the 12". At the same time, improved armor meant that it was now possible to provide adequate protection from the 6" across much of the ship's sides.

Dreadnought as she appeared in 1911

The initial response was the semi-dreadnought, with an intermediate battery of guns of 8"-10", attempting to split the difference between the 6" and 12" guns. This stopgap soon fell victim to the same problems that had killed the 6" guns. Improvements in both fire control and torpedoes pushed engagement ranges out to the point where better heavy gun mountings could fire as fast as the systems allowed, about 1.5 rounds per minute.

Jackie Fisher

Into this picture came John Arbuthnot "Jackie" Fisher. A brilliant, energetic, and innovative man, he was also stubborn and prone to obsession. Besides being the driving force behind Dreadnought, he was a major advocate of the submarine, a reformer in the Royal Navy's bureaucratic personnel system, inventor of the destroyer, and developer of what would become known as net-centric warfare. He was appointed First Sea Lord, professional head of the Royal Navy, in 1904, because he promised that he could control naval spending without sacrificing capability.1

Cuniberti's "Ideal Battleship"

Fisher was not the first person to think of the all-big-gun ship. In fact, until about 1902, he was one of the biggest advocates of the 6" gun as the primary weapon of the battleship, pushing for a reduction or elimination of the main guns until that point. The first commonly-known reference to an all-big-gun ship was published in the 1903 Jane's Fighting Ships by Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti, but thoughts in the US on the subject can be traced to 1901, and the British had also begun to work along similar lines before Cuniberti brought the concept to public attention.

Reginald Bacon

Fisher established a committee, including John Jellicoe and Reginald Bacon, who settled on the characteristics that would define Dreadnought. Bacon, later Dreadnought's first captain - regarded by Fisher as "the cleverest officer in the Navy" - was the man who convinced Fisher to switch from all-10" to all-12". Reports of the effectiveness of the 12" gun during the Russo-Japanese war helped confirmed this decision.

The second major change that Dreadnought brought is less obvious but in many ways more important. Dreadnought was the first large warship to use steam turbines instead of reciprocating engines. This increased her speed from the previous standard of 18 kts to 21 kts, saved 1000 tons, and most importantly allowed her to maintain high speed for much longer without the risk of mechanical failure. This was a vital component of Fisher's other innovation, what we now call net-centric warfare. The high sustained speed of the new ships allowed them to cover greater areas, based on the improved information gathering and dissemination system that Fisher set up.2

Dreadnought broke new ground in other areas, too. Her hull was about 18% lighter by volume than that of the proceeding Lord Nelson class, and she set a new standard for watertight integrity, removing most doors below the waterline. The only area without major improvement was armor, which was actually slightly lighter than in the Lord Nelsons.

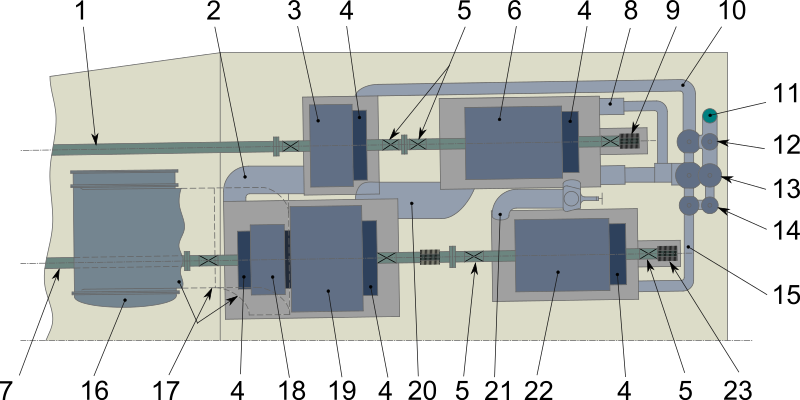

Design G, with single turret superfiring over two below it

The design process began in November of 1904, initially with plans for 6 turrets. The first set of designs included the obvious (a hexagonal layout), the slightly less obvious (three superfiring3 turrets on each end) and the weird (Design G, above, a triangle at each end, with two turrets abreast and a superfiring turret above them). Eventually, it was decided that muzzle blast made the later two designs infeasible. Blast interference between the wing turrets meant that the aft pair was replaced by a single centerline turret, producing the arrangement used in Dreadnought.

Dreadnought with HMS Victory

The final result was a ship of 18,000 tons and 527 ft.4 With an 8-gun broadside, she matched the long-range firepower of almost any two ship afloat, and she set a new standard for speed in battleships. She was laid down on October 2nd, 1905, and launched only 5 months later, on February 10th, 1906. The 14 months exactly from laying down to commissioning set a record that has never been broken for capital ships, and was intended by Fisher to send a message to the world that Britain could outbuild them in any new naval race.

Japanese battleship Satsuma

Dreadnought’s construction had been controversial, as Britain had just invested an enormous amount of money in a fleet of pre-dreadnoughts. It was feared that by introducing a new standard in battleships and rendering these ships obsolete, Britain would essentially be throwing away all of that money. Dreadnought’s rapid construction was intended to show that this would not be the case, and that Britain would be able to out-build any potential challenger. In practice, the idea was already in existence, and Japan had in fact laid down the battleship Satsuma, intended to be all-big-gun, in May of 1905.5

USS South Carolina (BB-26)

In the US, two units of the South Carolina class were ordered in March of 1906. They were smaller than Dreadnought at 16,000 tons, and 3 kts slower due to their reciprocating engines. However, they matched Dreadnought's broadside due to the use of superfiring turrets, a decision resulting from Congress's alarm over the growth of battleship designs and the need to economize on space and weight. At the time the design was chosen, it was not clear that end-on fire would be possible with superfiring turrets, but the American designers concentrated on the battleship as an element of the fleet, where it would fight on the broadside. Experiments in March of 1907, well before the ships commissioned in 1910, proved that this would not be a serious problem.

The perpetrators of the Dreadnought hoax. Virigina Woolf is on the left.

Dreadnought had a relatively undistinguished career. In 1910, the Dreadnought Hoax took place aboard her, while she was flagship of the home fleet. She was one of the few British batttleships that missed Jutland, as she was refitting at the time. Her only significant action was when she rammed and sank the submarine U-29 in March of 1915, a feat no other battleship was ever able to claim. She was taken out of service at the end of the war, and sold for scrap in 1921. Two years later, she was broken up in Inverkeithing, Scotland.6

HMS Dreadnought was one of the most influential warships of the 20th century, her all-big-gun armament and steam turbines setting the pattern for the rest of the battleship's life. While the concept was not unique to him, Jackie Fisher should get credit for pursuing it energetically and setting up Britain for the naval domination that ultimately was a major contributor to victory in the First World War.

1 At the time, the UK was facing a serious financial crisis as a result of the Boer War and the spiraling cost of building armored cruisers for trade protection and service with the battlefleet. ⇑

2 Fisher took this to a logical extreme with the early battlecruiser designs, essentially contemporaneous with Dreadnought. ⇑

3 Superfiring is the term for a turret above and behind another turret, firing over it when pointed fore/aft, depending on the layout. ⇑

4 Compare to Lord Nelson at 16,000 tons and 443.5 ft. ⇑

5 Satsuma was completed in 1910 with 4 12" guns and 12 10" guns due to problems procuring enough 12" guns. ⇑

6 For the record, in the course of writing this post I consulted a grand total of 12 reference books, as well as the internet. ⇑

Comments

I'm wondering about those two off-centerline turrets. It seems like they could have been replaced by a single forward-pointing centerline turret, slightly aft of and above the existing forward turret. It would have saved the weight of one turret while keeping the same broadside level of fire. Any idea why that wasn't done?

That's a superfiring turret, although it looks like I didn't define the term here. I've added a footnote to correct that. There were two reasons. First, tactics were a bit uncertain, and they wanted as much end-on fire as they could get. Second, the British put the sighting hoods in the top of their turrets, which meant that until either Queen Elizabeth or Hood (can't remember which offhand), they couldn't fire the upper turret within 30 degrees of the ship's axis or blast would make the lower turret very unpleasant. The arrangement you propose was the one adopted in the South Carolina class, but the US put the ports in the turret face, and they were more concerned with broadside fire.

Those posts sticking out from the sides of the ship, are they for hanging anti-torpedo nets?

The ones below the main deck? Indeed they are.

Am I correct in interpreting Kipling's "Ballad of the Clampherdown" as in part inspired by pre-dreadnought proposals for ships with very small numbers of very large guns? It was published in 1890.

David, the limit of that design strategy would be a ship with one enormous gun, probably fixed forward. Imagine designing a ship around Schwerer Gustav. It might need outriggers or a serious keel so it doesn't tip over when it elevates.

@David

The hundred-ton gun described was the 16.25″ gun used on Victoria, Sans Pareil and Benbow. The first two had a twin turret forward, while Benbow had single mounts at either end. The description matches her reasonably well. No proposals necessary.

@Johan

I'm not sure that's feasible. There would be lots and lots of other problems from a gun that big relative to the hull, such as seakeeping and recoil. Fortunately, we have a control for this in the form of monitors, which were pretty much intended to fit the biggest gun possible on a given hull. It was broadside instead of forward-firing, but the 18" on Lord Clive was fixed in train and only elevated.

The left-most hoaxer in the picture is Virginia Woolf!

That is true, but I absolutely loathe her after a bad experience in high school, so I didn't feel like calling her out.

"She was laid down on October 2nd, 1905, and launched only 5 months later, on February 10th, 1905." Love the series.

@James

Ah. I see the problem there. That should be February of 1906. (And I had design starting in November of 1905. Fisher built her fast, but not time-bendingly fast.)

What did you mean by "a triangle on each end"? Surely any hexagonal ship has a triangle on each end.

After a more careful look at the picture, I guess it refers to the positioning of the turrets.

That was talking about Design G. I don't think I knew I'd have an illustration when I was writing it. Yes, it's about the turret positioning.