Ships only sink when you let air out and water in. This fundamental truth was a problem during the age of the gun, as gunfire, while quite effective at disabling the enemy, is not particularly good at either. Even the occasional shot "between wind and water" was unlikely to sink the enemy very quickly. Shot also had a second problem, in that the guns to deliver it were large and expensive, and required big ships to carry them.

Cornelis Drebble

The obvious way to solve this was to use explosives, and the first man to make a serious attempt at this was Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel, who developed what we now know as the spar torpedo as a weapon for his submarine, the first ever to successfully navigate underwater. His concept was extremely simple, a bomb on the end of a stick, which would be set off in contact with the enemy ship. Details about use are unclear, but he was a consultant to the British Admiralty for several years before they apparently became disillusioned with the idea and fired him.

It would be a century and a half before the next development in underwater weapons, again driven by the desire to attack entirely submerged. The protagonist this time was David Bushnell and the enemies were the British, who were rather upset that their colonies in America were thinking about setting off on their own. He developed a human-powered submarine, Turtle, and to arm her, a weapon that he called a "torpedo" after a type of electric ray. The idea was that Turtle's operator would sneak up on an anchored enemy ship, attach the "torpedo", and then retreat while a time fuze set it off, making it the ancestor of what we would today call the limpet mine, although "torpedo" would remain the generic term for any underwater explosive weapon for the next century or so.1 The first attempted use against frigate Eagle failed and nearly asphyxiated the pilot, Sgt. Ezra Lee. After several subsequent attempts failed, he turned his attention to floating charges that he hoped would drift against the enemy. Unfortunately, these also failed to help get rid of the pesky British.

A model of Turtle at the Submarine Force Museum, Groton, CT

One artifact from this has survived, the so-called Fleming Keg Mine, a wooden keg that would be filled with gunpowder and set off when a passing ship bumped a wooden arm that in turn would trigger the flintlock mechanism from a Brown Bess musket. Details on utilization are not certain, but it appears that this was a different take on the drifting mine, either related to Bushnell's efforts or a separate attempt to attack the Royal Navy.

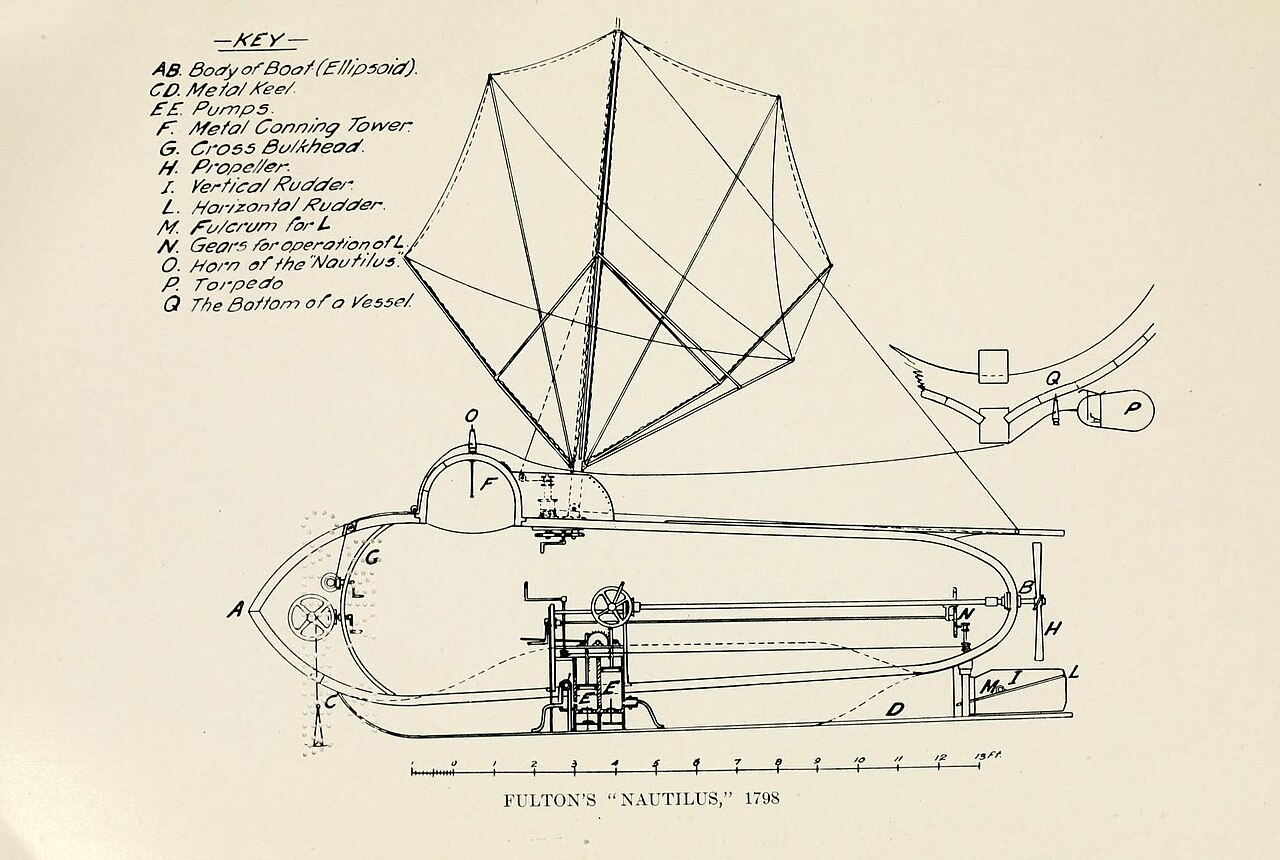

In any case, these experiments were largely overlooked at the time, and it would fall to another American, Robert Fulton, to bring underwater weapons into the mainstream. While Fulton is most famous for creating the first commercially successful steamboat, he also created what was probably the first vaguely practical submarine in history, Nautilus, while working for the French in 1800. Fulton planned to arm it with a Bushnell-style limpet mine, which ignited an interest in underwater weapons.

Fulton's Nautilus

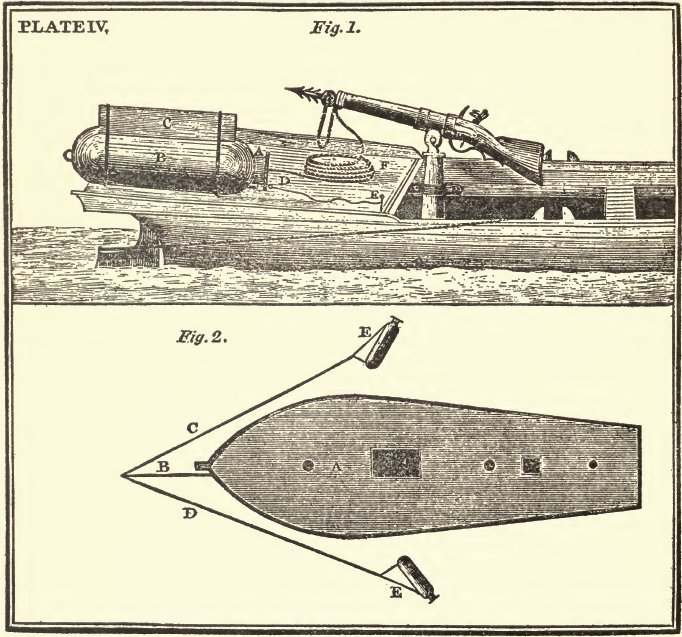

Nautilus itself was soon abandoned, but Fulton continued work on ways of attacking ships below the waterline, coming up with both the first definite example of a moored mine and a new kind of weapon, the towed torpedo. This was what it sounds like, an explosive charge towed behind the ship. In Fulton's initial test, the towing vessel simply turned to swing the torpedo into the target, and the weapon was set off by the impact. The test was successful, but changes in French policy saw them decline further help from Fulton, and the British managed to lure him away. They decided that the submarine wasn't practical, but that his torpedoes might be of use in attacking the invasion force the French were assembling on the English Channel. These were drifting mines and came in two sizes. The larger was a two-ton vessel 21' in length, filled with 40 barrels of gunpowder and ballasted so that its deck was almost awash. It would be moved into position by a ship's boat, the time fuze set, and the device released to be carried by the tide into the enemy's ships, where its grapple would hopefully snag an anchor cable and the current would carry it alongside before the clockwork fuze set it off. The smaller involved a pair of barrels connected by a rope, the idea being that the rope would likewise snag the mooring cable and the barrels would be up against the ship when they went off. These were first sent into action in late 1804 against the French at Boulogne alongside more conventional fireships, but none of the British devices proved effective.

Fulton's torpedoes as used in his demonstration, as well as a later plan

Work on the devices continued, and while effective use against the French proved elusive (the only known example of one actually catching an anchor cable resulted in minimal damage to the French ship), Fulton was able to demonstrate its potential in a trial against a target ship, which saw it broken in half by the charges. The plan evolved was for a force under the command of Sidney Smith to attack with a combination of Fulton's weapons and Congreve rockets, which would hopefully distract the French from the approaching "torpedoes". The main target for this scheme would be Cadiz, where the combined Franco-Spanish fleet was based, but while preparations were underway (including an ineffective use against Boulogne in October 1805), the fleet came out and was destroyed at Trafalgar, effectively ending British interest in Fulton's scheme. Fulton instead returned home to America, where he spent the next few years focused on his steam boat.

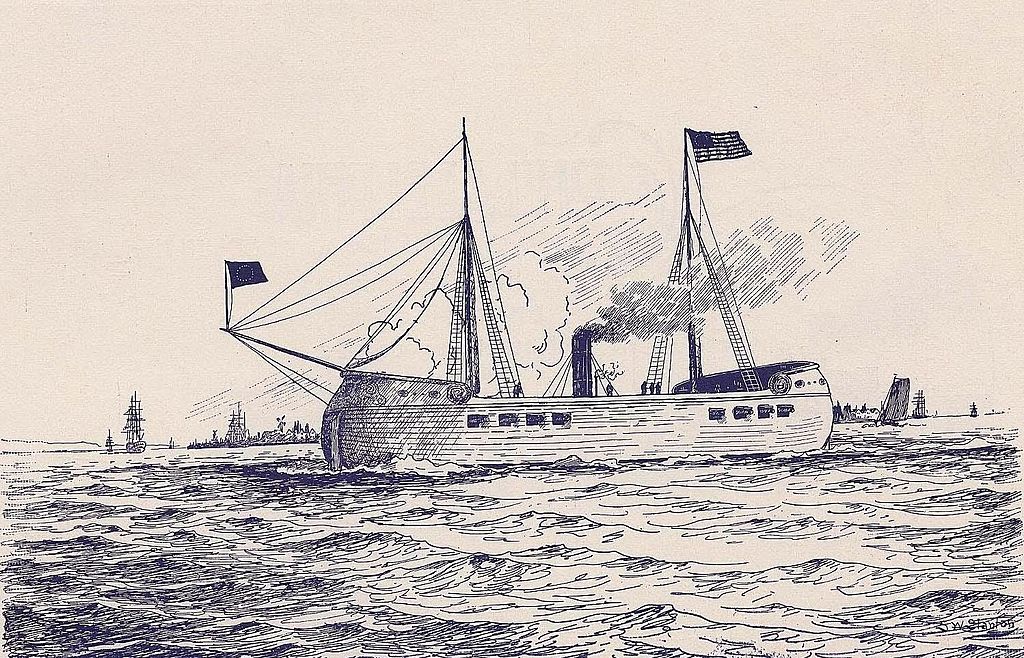

Demologos

But Fulton wasn't done with attacking ships, and he quickly came up with another idea, a harpoon gun with a timed explosive charge attached to it by a 60' line. After the harpoon was embedded in the side of the ship, the charge would be drawn alongside by the ship's motion, when it would then detonate. This was never tested properly, and Fulton soon moved on to an underwater gun powered by compressed air, which in theory would be able to attack the underside of a target. This was apparently enough to get all the crazy out, and he moved on to working on the spar torpedo around 1813, possibly driven by the fact that there was an actual war on and he wanted useful weapons. Fulton helped with a number of underwater attack schemes during the War of 1812, although his attention was more focused on a scheme for a steam-powered battery to defend New York, which he eventually built in the form of Demologos, the world's first steam-powered warship. Unfortunately, the war ended before it could see action, and it was renamed Fulton after its inventor who died weeks after the end of the war. On the underwater warfare front, Fulton had inspired numerous imitators who attempted to attack the British, primarily with drifting mines and Turtle-type submarines, but none did any damage.

Pavel Schilling

While all of this was going on, work in Europe was continuing, leading to the development of the next step in underwater warfare. Scientists were experimenting with electricity, and several, drawing on primitive work with the telegraph, became interested in the idea of detonating a charge remotely using this new technology. The pioneer of this work was Russian-German nobleman Pavel Schilling, who ran several successful tests in between his service during the Napoleonic wars. This concept, known as the "controlled mine", would be an important part of coastal defenses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but neither Schilling nor his contemporaries were able to solve the problem of knowing when to detonate the mine, making it of only dubious value.

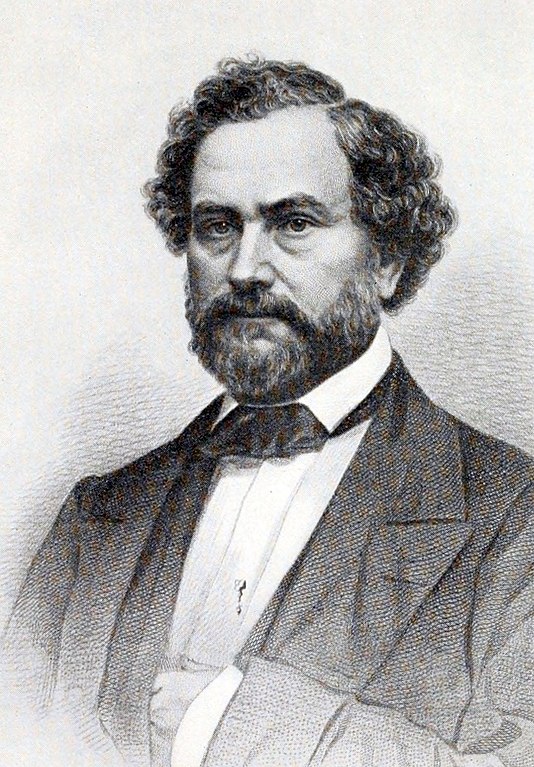

Samuel Colt

This problem would be solved by an American is far better known for his other activities. Before he turned to making men equal, Samuel Colt was interested in setting off explosives underwater using electricity. His experiments began during his teenage years, but picked up steam in the 1840s, when he sold Congress on a plan to use his submarine mine to blow up vessels well outside gun range. Two operators taking cross-sightings from shore would make sure that the target was over the mine before setting it off, and in 1844, he successfully demonstrated this system on a towed target during a test on the Potomac. Unfortunately, he had antagonized both the Army and Navy in the process, and the system was ultimately not adopted as part of the American program of coastal defenses.

But it wouldn't be long before the underwater weapon would get its first serious test in combat, as war broke out between Russia and an unlikely alliance of Britain and France, and the Russians deployed various kinds of mines, particularly in the Baltic. On July 9th, 1855, paddle packet HMS Merlin struck one, a moored contact mine, and although it did little damage, it ushered in a new era of warfare. The various types of mines described here would soon be joined by the locomotive torpedo, invented by Robert Whitehead, and would overthrow the basic model of naval warfare that had held for centuries.

1 Hence the famous "damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" actually refers to naval mines. ⇑

Comments

"Unfortunately, he had antagonized both the Army and Navy in the process"

I assume they got over it, since Colt's would go on to sell them handguns in job lots later

@bean: "unlikely alliance of Britain and France..." and the Kingdom of Sardinia, a great-great-great uncle was there in the Sardinian heavy cavalry.

@Ian

Apparently, this experience taught him important lessons about what not to do when trying to get military contracts.

@Emilio

If we're nitpicking my description of the Crimean War, I think the omission of Turkey is a much bigger error. Interesting about your great great uncle, though.

No nitpicking, only family history. :-)

It was also the preparation of the four Independence Wars that unified Italy.