In early April, 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a few desolate rocks in the South Atlantic, and the British mobilized their fleet in response. The carriers arrived off the Falklands on May 1st, swiftly defeating the Argentine Air Force. The Argentine Navy tried to interfere the next day, but withdrew after the cruiser General Belgrano was sunk by a submarine. Two days later, the Argentines struck back, sinking the frigate Sheffield with an Exocet missile. The next two weeks saw a siege of the islands while the British waited for their amphibious force to arrive.1

Fearless in San Carlos Water

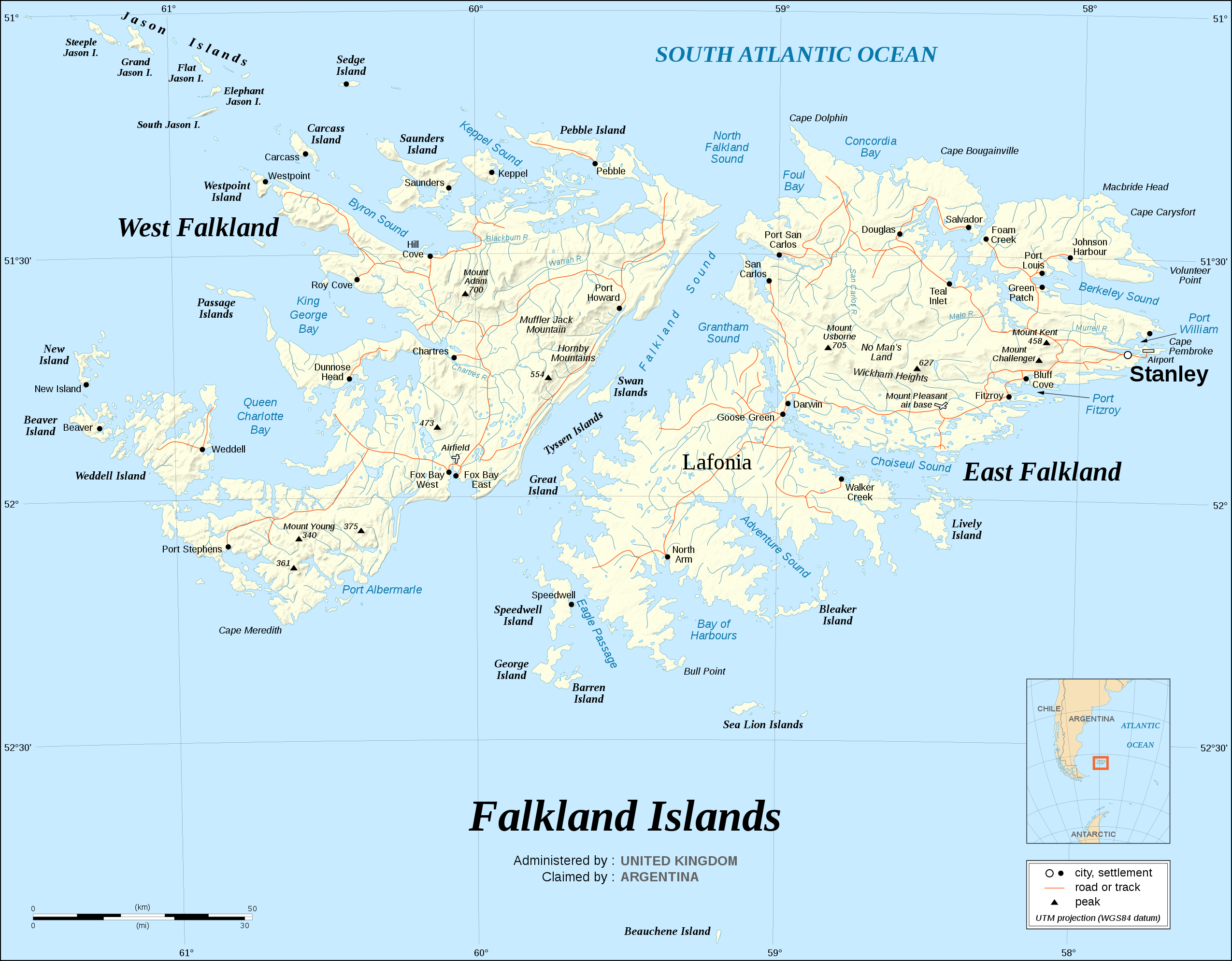

Planning for the amphibious assault had begun while the task force was still on the way to Ascension, and Admiral Woodward's staff discussed a number of different options. The idea of a direct assault on the area around Port Stanley was quickly ruled out. While it was undoubtedly the most important location on the islands, this had led the Argentine garrison to concentrate most of its strength around the city. Amphibious operations are extremely difficult, and the British didn't think they had the strength to make a frontal attack. Another plan was to land on the lightly-held West Falkland and use it to either force a settlement or as a base for the recapture of East Falkland. This was also ruled out, as it would have placed the beachhead closer to the mainland air bases, raising the risk of air attack, and required a second landing on East Falkland later on. Besides the peril of the landing itself, this would have also pushed the end of operations back into late June, when severe winter weather would have made continued operations very difficult. Several different beaches on East Falkland were examined, and the planners eventually settled on San Carlos Water, a bay off Falkland Sound in the northwest corner of the island.

This decision, which placed the troops 50 miles from Stanley across mostly-trackless hills, seems rather strange, but there were good reasons for it. First and foremost, it was pretty much undefended, except for a small observation post nearby. Second, it would give a good, protected anchorage for the transport ships. Third, the terrain made it fairly easy to defend from Argentine counter-attacks, either by land or, at least in theory, by air, due to the limited run-in aircraft could make. Fourth, it was Exocet-proof. Even before Sheffield was sunk, the British were worried about Exocet, but the missile's radar would be confused by the mountains. Good beaches would make it easy for 3 Commando Brigade to secure a foothold on the Falklands, although the initial plan had them waiting until they were joined by 5 Infantry Brigade to break out and drive for Stanley.

San Carlos Water

The run-in to the landing began shortly before noon on May 20th, when the Amphibious Group split off from the carriers. Each of the infantry battalions was now in a separate ship, in a bid to reduce casualties should something go wrong. 40 Commando had transferred to Fearless, the LPD2 flagship of the Amphibious Group, while her sister Intrepid bore 3 Para. 42 Commando remained aboard the liner Canberra, while the stores ship Stromness and the ferry Norland carried 45 Commando and 2 Para respectively. They were to be joined inshore by the LSLs,3 loaded with supplies, the stores ship RFA Fort Austin, functioning as a helicopter carrier, and the requisitioned Europic Ferry, carrying more equipment for the landing force. They were escorted by the old destroyer Antrim, the frigates Ardent, Argonaut, Plymouth and Yarmouth, and, as an indication of how seriously everyone took the threat of air attack, both of the Type 22 frigates in the South Atlantic, the only ships with good point-defense missiles.

Troops going ashore from Intrepid's landing craft

The invasion began at 2200, when Antrim flew off a party of SBS troopers to take out an Argentine observation post on Fanning Head, overlooking the entrance to Falkland Sound.4 A total of 37 men went ashore, and after a brief bombardment from the destroyer's guns starting at around 0100 on the 21st, an interpreter called on the twenty-strong Argentine party to surrender. They refused, and the SBS team stormed their position, killing about half the defenders and capturing the rest. Diversions were also in the works. The destroyer Glamorgan was bombarding targets north of Stanley, while the SAS launched a raid around Darwin and Goose Green, 15 miles south of the beaches, successfully keeping the garrison there from intervening.

Fearless and Intrepid passed through the narrow entrance to Falkland Sound at 2245, and anchored to begin launching their landing craft, a total of 8 LCUs and 8 LCVPs at 2320. The rest of the troop-carrying ships followed over the next hour. The commander of the landing craft was Major Ewen Southby-Tailyour, an enthusiastic yachtsman. While serving as commander of the Marine garrison in the Falklands, he had taken copious notes on the coast, which now proved invaluable. Fearless embarked 40 Commando directly onto her craft, accompanied by a pair each of Scorpion and Scimitar light tanks, while Intrepid dispatched hers to Norland to load 2 Para. Both units went ashore around 0330, with the Marines landing near San Carlos in the southern arm of San Carlos Water and 2 Para hitting the beach slightly further south. The Paras took up positions in the Sussex Mountains to the south of the bay, while 40 Commando set up their defenses in the Verde Mountains to the east.

Landing craft carrying troops ashore

The landing craft swiftly returned to the transports to take the second wave ashore. 45 Commando from Stromness would go ashore near Ajax Bay to the west of San Carlos, while 3 Para would secure the area around Port San Carlos5 on the northern arm of San Carlos Water.6 By this point, delays had started to pile up, to the point that the LSL Sir Percival grounded at Ajax Bay just ahead of 45 Commando. Unfortunately, the delay to 3 Para proved fatal for a Gazelle helicopter, which was shot down while reconnoitering the area around Port San Carlos and crashed into the water. The crew escaped, but the machine gun that had downed their helicopter opened up on them, and the pilot, Andy Evans, was killed. A second Gazelle appeared 15 minutes later, and was also shot down, killing both crewmen. For some reason, a third helicopter was then sent in, but it escaped with 10 bullet holes. Understandably, helicopter operations near Argentine forces were swiftly curtailed, although the Argentine defenders withdrew before 3 Para could come to grips with them.

A Westland Gazelle

Air support came in the form of Harrier GR3s from the carriers, two of which strafed a helicopter base near Mount Kent, destroying three aircraft on the ground and delaying any response by heliborne troops. Another GR3, informed that there was no need for its ordnance near the beaches, was shot down while on a recon run over Port Howard on West Falkland. The pilot ejected and was taken prisoner.

RFA Sir Galahad loads LCUs in San Carlos Water

As dawn broke, the landing swung into high gear. The 105 mm guns of 29 Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery and the Rapier missiles of T Battery were lifted ashore via helicopter, although the delicate Rapiers took time to load and setup. Eight Sea Kings would lift 407 tons of equipment and 520 men before the day was out. Every boat available that could run up on the beach was also put to work, primarily to bring ashore enough ammunition to sustain the Brigade during a possible Argentine counterattack, and the transports anchored in San Carlos Water to shorten the trip.

Helicopters and landing craft unload supplies

By going ashore, the amphibious force had given up the mobility that is one of the great assets of naval forces. Now, they would have to face the attempts of the Argentine Air Force to disrupt the invasion, and those efforts would not be long in coming.

1 I've written a glossary to make it easier to keep track of terms in this series, and the full list of posts is here. ⇑

2 A sort of general-purpose amphibious ship, equipped with a well deck for landing craft and the capacity for a large group of troops. ⇑

3 Landing Ship Logistics, basically a modernized version of the WWII Landing Ship Tank. ⇑

4 I'm not entirely sure why they bothered, because it was the least effective observation post in history. They had missed numerous transits of the Sound by British warships, a flaming freighter, and the entire amphibious force anchoring right under their nose. ⇑

5 Port San Carlos is a completely different town from San Carlos. I didn't choose the names. ⇑

6 The civilians of the area were grateful to be liberated, and vehicles which had been irreparably broken during the occupation immediately began working day and night, while the women produced vast quantities of tea and children helped dig trenches. ⇑

Comments

I spent some time trying to find out if Stanley (population about 2,500) is a city. Hamilton, Bermuda has a smaller population and is, but I don't think Stanley is.

I found out that Stanley does have a cathedral. Hamilton was made a city when its cathedral was consecrated, but a cathedral is no longer necessary or sufficient for city status in the UK- Cambridge is a city with no cathedral, while Bury St. Edmunds is a town which has one.

Stanley Cathedral is also weird because officially, the Bishop of the Falkland Islands is the Archbishop of Canterbury (ex officio). He, in turn, nominates another bishop to be Bishop for the Falkland Islands- recently, this has been the same person as the Bishop to the Armed Forces who, again, lives in London. So effectively it's a cathedral without a bishop.

That's very interesting. I think I knew there was a cathedral there, but, being American, didn't start making connections. Occasionally, I end up going down the rabbit hole of non-war-related Falklands articles, and it usually ends up being rather strange. Like their government, which has two constituencies, one for Stanley and one for everywhere else.

The timing of the bombardment/capture of the observation post seems really strange to me, I feel like you would want to shut that down before your landing force anchors. Also it seems some of the trouble with the helicopters was that they were flying over directly over the Argentine position at Fanning Head en route to the beachhead. Taken together I'm not sure I'm convinced the English knew where the Argentine position was until they started firing.

That was a strange episode, and one I don't fully understand. You don't dump that many troops in an area where the enemy might have an observation post, and every account I have is unequivocal that they were expecting the one they found. One of the big problems Argentina had was that after the initial invasion, they pulled out most of the long-service Marines who had conducted the initial invasion and replaced them with Army conscripts, who didn't really want to be there. I suspect that contributed a great deal to things like the worst observation post ever.