In early April 1982, Argentina invaded the British-controlled Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. The British, instead of accepting the fait acompli, mobilized their fleet. After a fierce battle in the air and at sea, the British gained the upper hand, and began landing troops on May 21st at San Carlos Water on the west coast of East Falkland. The Argentinians attempted to defeat the invasion with air attacks, but the British eventually prevailed, inflicting heavy losses. On the 28th, the British began the ground campaign, defeating the Argentinian garrison at Goose Green and opening the way to lay siege to the main enemy positions near Stanley. The first days of June saw the islands shrouded in clouds, but that didn't prevent the British from leapfrogging forward to Fitzroy and Bluff Cove, just to the south of Stanley. There, tragedy struck on June 8th, when an air attack caught several ships unloading. This didn't stop the British from launching their assault on the hills surrounding Stanley on the night of the 11th, securing three major hills. Two days later, the final assault took the last pair of hills, and the Argentine commander surrendered the next morning.1

A Chinook lifts the damaged Wessex from Glamorgan

The weather in the Falklands had been bad, with Wireless Ridge and Mount Tumbledown being taken among scattered snowstorms. But on the 15th, the snow started in earnest, with several ships reporting the worst seas they'd seen since entering the South Atlantic. The ASW Sea Kings were withdrawn from the carrier's screen for the first time in over a month, and a Wessex (borrowed from Tidespring) on the deck of Glamorgan was badly damaged. The North Sea ferry Europic Ferry was being used to prep a Chinook brought south by Contender Bezant, and she rolled so badly that her crew seriously considered jettisoning it. Ultimately, the helicopter came through undamaged, and flew off when the weather moderated on the 16th.

Argentine POWs in the streets of Stanley

Ashore, the British had a serious problem. About 8,000 soldiers were in Stanley itself, and thanks to incompetent logisticians and the British blockade, they had only about three days worth of food and very limited shelter. The problem would only grow when they secured the 4,000 other soldiers scattered throughout the rest of the islands, mostly on West Falkland. Previously, prisoners had mostly been turned over quickly, but the Junta still had not confirmed their acceptance of the ceasefire, and the British were concerned that anyone they released might end up back in combat against them. Thanks to heroic efforts by the British logistical staff, everyone was housed and fed, and an agreement to repatriate prisoners was reached relatively quickly, with Canberra taking aboard the first load from Port Stanley on the 16th. She wasn't able to enter the harbor proper for the next day due to mines, although these were promptly swept. RFA Sir Percivale was dispatched immediately to serve as an R&R platform for the Paras and Marines, who were able to get a hot shower and a meal. Canberra sailed on the 18th for Puerto Madryn, Argentina, with 4,167 prisoners onboard.

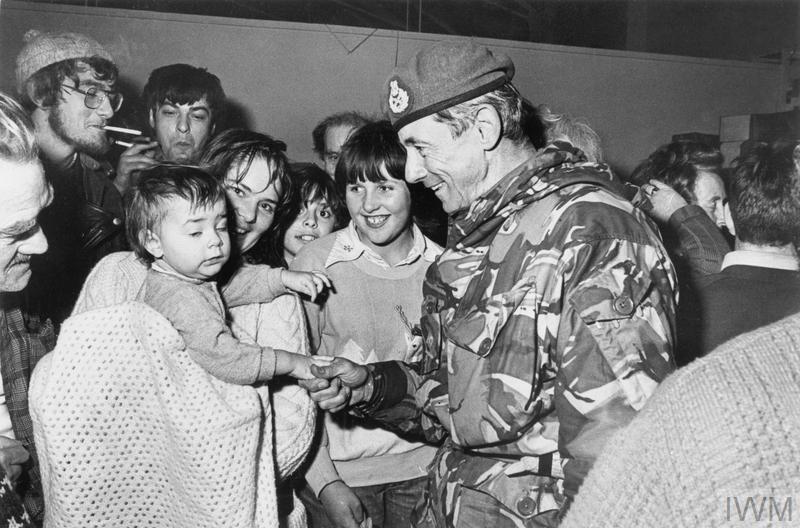

General Moore, commander of the British troops, is greeted by the islanders after the surrender is announced

Despite their victory, the air and naval forces were unable to relax. The surrender only applied to the forces on the Falklands, the risk of more air strikes or even a sortie by the Argentinian Navy remained real. The Junta that ruled Argentina had started the war to quell increasing social unrest and distract the population from serious economic problems. It wasn't out of the question that they would attempt one last do-or-die effort to salvage their regime, and CAP and ASW missions continued. Fortunately, they didn't, and General Galtieri resigned on June 18th. The resulting chaos meant it was another three days before informal assurances reached the British that the government wasn't particularly interested in continuing the war, and the British began to rotate their ships home.

The Argentine camp on South Thule

While they were waiting, the last act of the war played out. The Falklands and South Georgia weren't the only islands in dispute, and Argentina had established a military weather station on South Thule, 450 miles southeast of South Georgia and even more desolate, in 1976. Diplomatic protests had been unable to remove them, and it would now be done by force. Yarmouth and Olmeda were dispatched from the Falklands to South Georgia on the 15th, where they joined Endurance and tug Salvageman and loaded units of 42 Commando. On the 19th, they arrived off South Thule and put a recon team ashore. The next day, just before Yarmouth was scheduled to begin a firepower demonstration, the 10 remaining soldiers on the island surrendered, and the reconquest of the British possessions in the South Atlantic was complete.2

Invincible off the Falklands

Invincible had been having trouble with one of her engines, and on the 18th, she and Andromeda had detached from the task group and headed 3,000 miles northeast. Her gas turbines had been designed to be changed while at sea, and the spare carried aboard was installed successfully in only six days. She then returned to the Falklands, relieving Hermes in the air defense role. The older carrier began the trek back to England, arriving at Portsmouth on July 21st.

Hermes returns to an enthusiastic welcome at Portsmouth

Nor was Hermes the first of the task force to return home. On the 21st, Plymouth and Glamorgan were released, the same day that Glasgow, detached after battle damage, reached Portsmouth. They were followed four days later by the men of 3 Commando Brigade, loaded in Canberra, Norland and Europic Ferry and escorted by Alacrity. That same day, Sir Galahad was towed out to sea and scuttled by a torpedo from HMS Onyx.

RAF Mount Pleasant

There was still the issue of long-term defense of the islands. Despite the cease-fire, the Argentine government refused to agree to any official negotiations that did not include some discussion of sovereignty over the Falklands. The British, citing the islander's desire to remain British and conscious of the political implications of weakness in the wake of the war, refused, and began making plans to protect it from renewed aggression. The plan selected was to build a major airbase at Mount Pleasant, southwest of Stanley. It would house a detachment of fighters and a refueling tanker for air defense, and allow the company-sized permanent garrison to be quickly reinforced in the event of a crisis. A warship would also be kept on station during the summer months. But until the first primitive facilities for fighters could be set up, a carrier needed to stay on station.

Illustrious sorties for the Falklands, with sister Ark Royal completing in the background

To replace Invincible, her sister-ship Illustrious had been rushed to completion, being formally accepted by the Navy on June 18th, and becoming the first-ever RN warship commissioned while at sea on the way to Portsmouth on the 20th. There, she was hastily prepared for service in the South Atlantic, most notably being fitted with American-supplied CIWS systems to protect against more Exocet attacks. While waiting for her to arrive, Invincible was allowed within sight of land for the first time in 98 days on July 12th. Her sister arrived off the Falklands on August 27th, bringing with her 10 Sea Harriers and 10 Sea Kings, two of which had been modified with the Searchwater radar to give the Airborne Early Warning capability that had been so sorely lacking during the campaign. Invincible and Bristol reached home on September 17th, and their return was carried on live TV, bringing an end to the war for the man in the street. The Phantoms finally arrived on October 17th, and Illustrious sailed for home four days later.

A Sea King with the Searchwater radar over Invincible

Things were not so rosy in the other combatant. The Junta staggered on for another year, until elections were held in 1983. Two years later, many of its members were placed on trial for their actions during the Dirty War. Unfortunately, this setback for Argentine nationalism didn't last. In 1989, Britain and Argentina resumed diplomatic relations, but the "Malvinas" remain a major sore spot in Argentina to this day. In 1994, a Constitutional amendment defined the "Malvinas", as well as South Georgia as Argentinian territory, and successive governments have used the issue to boost their popularity. They regularly protest to the UN and make rather absurd charges of colonialism, claiming that the current inhabitants don't count for some reason.3

Port Stanley

Throughout the process, the British have maintained the position that the question must be decided by the islanders themselves, and in 2013, they held a referendum asking if the islanders wanted to keep the status quo or seek other options.. The result was 92% turnout and the sort of support for remaining a British territory usually only found in dictatorships conducting sham elections to legitimize themselves.4 Since then, there's been a regular war of words between the two sides, but the decay of Argentina's military forces has made a resumption of hostilities increasingly unlikely. Most of their fleet is stuck in port thanks to a lack of spares, and even the operational ships average less than two weeks a year at sea. The rot is deep enough to actually make the ships unsafe to operate. Mothballed destroyer Santsima Trinidad capsized while tied up to the pier in 2013, while submarine San Juan was lost at sea four years later. The British have maintained their forces in the South Atlantic, and could easily win another air-sea conflict if one was to break out.

HMS Prince of Wales sets forth on her maiden voyage

The Falklands War remains the largest air-sea conflict since the end of WWII, and many lessons could be drawn from it. It illustrated the ability of naval forces to project power far from home, and the continued utility of the surface ship in the face of air threats. Important lessons were learned which would go on to pay dividends for Britian and her allies in future conflicts. It also marked the dawn of a new era for the UK and its military, reinvigorating a Royal Navy that had been facing massive cuts. In many ways, the new Queen Elizabeth and Prince of Wales are the direct result of the Falklands.

This brings us to the end of the main series on the Falklands. It's been almost two and a half years, and I've enjoyed it greatly. But at the same time, I couldn't hope to cover a conflict of this size comprehensively even in two dozen posts, and I've picked up quite a few books while I was writing. I expect to follow this with more focused accounts of specific aspects of the war.

And thank you guys for reading and commenting.

1 For more information on ships and aircraft, as well as links to the whole series, see my Falklands Glossary. ⇑

2 The next time the British visited South Thule, they discovered that someone had lowered the Union Flag and raised the Argentinian flag. The culprit was never found, but the base was demolished to prevent future problems. ⇑

3 The resentment is deepest among the inhabitants of the southern parts of Argentina, where many of the forces that fought the war were based. This has occasionally led to some very bad behavior towards innocent British television crews, which I suspect did a lot of damage to world sympathy for Argentina. ⇑

4 To be completely clear, the election was certified by international observers as fair and free. 99.8% of valid votes were in favor of remaining as a British territory. One of them made his allegiance very clear with the clothes he chose to wear. This is the only election I know of where the Lizardman's Constant didn't show up. ⇑

Comments

Looks like a sentence got clipped during editing.

Oops. Should be fixed now.

Thank you so much for this series! It has been a blast, I can't believe that it was started two years ago!

I appreciate the "comtemporary" setting, and it's a nice bit of variety

I've been riveted by this series from the beginning, Bean. Thanks for seeing it through with rigor and style!

Re: lopsided elections Surely the Saar Plebiscite is similar with a 180:1 result Germany over France. I guess, in general, surrendering to an enemy nation is unpopular.

You guys are most welcome. It's been interesting, and I definitely plan to come back to the exemplars we have of modern naval warfare before too long. It's currently a tossup between Libya and the Persian Gulf in the late 80s.

@bobbert

That was 90.7% Germany, 8.9% status quo, 0.4% France. Not quite the same thing.

Thanks for the series! It was the most recent war when I was growing up, and the way different people talked about it was really confusing for me as a kid (my friend's dad at the football club vs my mom's teacher friends).

The actual events were hardly ever discussed, so this was a great introduction to what really happened.

My only criticism is that we never heard how the sheep felt about everything. At least the invasion didn't interrupt lambing season, which would have happened around September.

Was going to suggest the Iran-Iraq Wars leading up to the Tanker Wars and PRAYING MANTIS as your next series (if you want), but I see you are already thinking about it

I picked up a book on that last year during the USNI sale called Into the Danger Zone. Would recommend it if you're interested in that era. But I also got one on Libya, and am trying to pick between them (at least first).

I've read Zatarain's book (with its confusion between titles and subtitles), and greatly enjoyed it. I'll add Inside the Danger Zone to my list.

What is that capsule-shaped thing on the side of the Chinook cockpit?

Nevermind, it appears to be a winch. I either never saw or never noticed that before.

Important lessons were learned which would go on to pay dividends for Britian and her allies in future conflicts.

This sounds worthy of further work.

Oh, we'll get there at some point.

I also thought that this series was great, and eagerly await it's successor.

Sad to hear that the Indians have just started breaking up Hermes/Viraat. It would have been nice if the campaign to make her a museum had been successful. Still, not a bad life considering that she was commissioned the decade after BB-61.

@Alexander

And laid down less than a year after Iowa was commissioned!

The name lives on to some extent- Hermes is the name of the shorebased simulator used to train engineers for the new Queen Elizabeth-class carriers.

Really awesome series! Enjoyed reading about it for the last 6 months as I got caught up haha.

Thanks for writing this.

It has particular resonance for me as I was at a Navy boarding school while it was happening (my father had just left the Royal Navy) and I am from a naval town (Gosport). Sadly, several children at my school lost their fathers in the conflict.

I have heard that the Royal Navy had got a bit complacent by the Falklands, to the extent that they had nylon uniforms (which can give horrible burns) and had lots of flammable stuff in the crew messes (such as wooden furniture). But that is just from memory and I don't have any sources for that.

You're welcome, and I'm glad you enjoyed it.

Re damage control and complacency, I know I've read that lessons from the Falklands were important in the survival of Stark and Samuel B Roberts in the Persian Gulf.