In early April, 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a tiny cluster of land in the South Atlantic. The British mobilized their fleet to retake them, staging out of Ascension Island. On the 25th, a force retook South Georgia, a small island that Argentina had also captured, while the main task force closed on the Falklands themselves.1

Six days after South Georgia fell, the British launched their first strike on the Falklands. The carriers had finally reached the South Atlantic, and were about to begin the campaign for air and sea superiority within the 200-mile Total Exclusion Zone. However, the honor of the first strike fell not to the Navy but to the Royal Air Force.

XH558 from below

The recapture of the Falklands was obviously going to be primarily a naval operation, but the RAF, fearful of getting left out, started looking for a way to contribute directly, instead of merely flying supplies into Ascension and conducting an occasional Nimrod sweep near the Task Force. They quickly settled on the Avro Vulcan, Britain's only remaining operational bomber. The Vulcan was scheduled to be retired in June, with only three squadrons still in service, all assigned to the nuclear strike mission. None had practiced conventional bombing in years, and the airplanes would have to be refitted with the bomb racks and control systems to carry conventional weapons. Jamming pods were fitted to the hardpoints originally designed to carry Skybolt missiles two decades earlier.

But those were minor problems when compared to the 6,600-nautical mile trip from Ascension to the Falklands and back.3 The Vulcan had been designed as a medium-range bomber, to strike targets in the western USSR, and could manage barely a third of that on internal fuel. Aerial refueling was the obvious solution, but the Vulcans had lost their refueling probes years earlier. Supply depots and air museums were asked to look for any available probes, and one team even flew to California to retrieve one from a Vulcan on display there.4 Their navigation systems were also inadequate for the trip, and improved inertial navigation packages were installed.

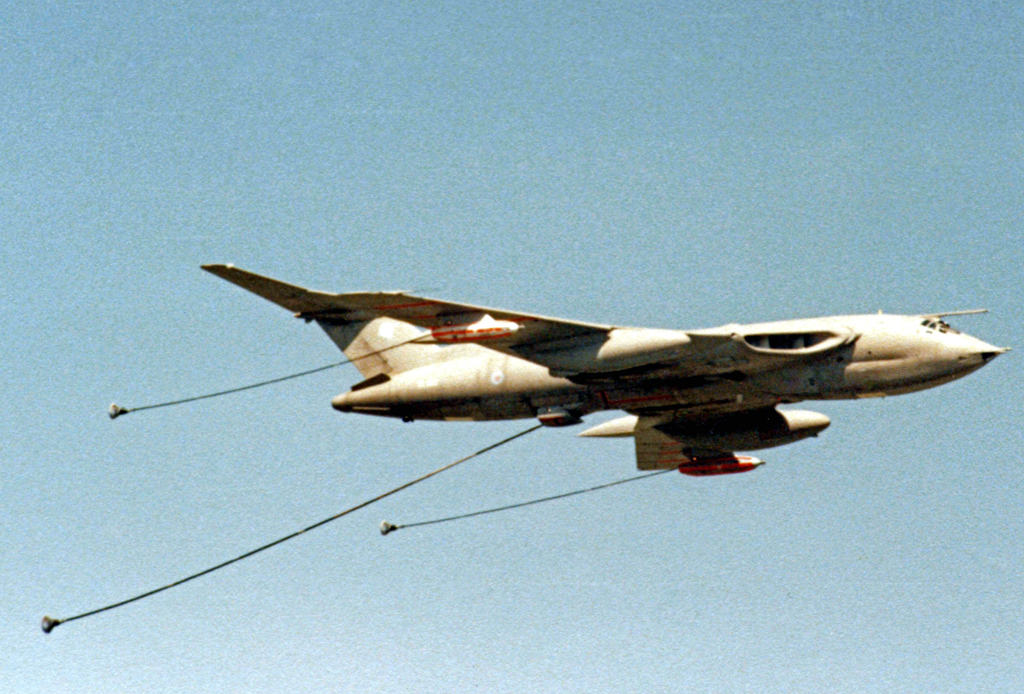

Victors on Ascension

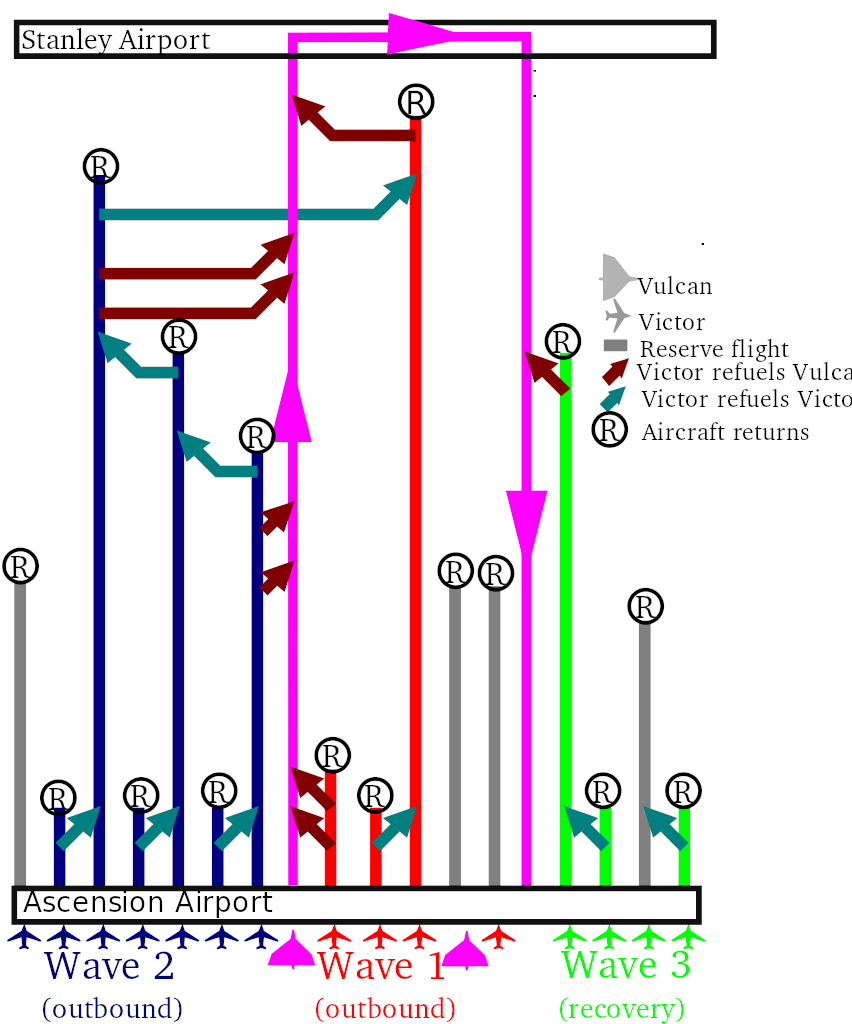

Finally, shortly before midnight on April 30th, the first raid of Operation Black Buck took off from Wideawake. The two Vulcans, one primary and one reserve, were supported by eleven Handley Page Victor tankers.5 The Victors had also had to be upgraded with improved navigation systems to support the long overwater flights, and their ability to receive as well as give fuel had allowed them to provide reconnaissance support for the recapture of South Georgia. Several of the planes, after turning over their first load of fuel, would sortie a second time and support the airplanes on the way back from the bombing mission. In total, 15 sorties and 18 aerial refuelings would be required to deliver 10.5 tons of bombs to the Falklands.

The complicated refueling scheme required for Black Buck

Shortly after getting airborne, the primary bomber, Vulcan XM598, suffered a pressurization failure and had to turn back,6 leaving the reserve, Vulcan XM607 under Flight Lieutenant Martin Withers, to carry on the mission.7 One of the Victors also had refueling system problems and had to be replaced by the reserve tanker.

After the second refueling, more tankers were drained and turned for home, leaving just three aircraft, two Victors and the Vulcan. Murphy's law placed the last refueling between the two Victors over a thunderstorm, delaying the hookup between the two aircraft. Worse, the refueling probe on the Victor intended to make the final refueling, XH669, broke, forcing the two aircraft to swap places. XL189 took on the fuel it had just passed over, along with the extra necessary to carry the Vulcan to the Falklands and on to the refueling rendezvous on the return leg. There was a danger that XH669's broken probe had blocked the basket of XL189, but the Vulcan flew in close and inspected the basket, which appeared to be clear, with a flashlight.

An RAF Tornado conducting a probe-and-drogue refueling8

Unfortunately, the drama wasn't over. The problems with the refueling had cut deeply into XL189's margins, and the crew had to pass over 7,000 lbs less fuel than had been planned to the Vulcan at the last refueling, cutting XM607s reserves in half. Even what they retained would not be enough to get them back to Ascension unless they were refueled, but the need for radio silence meant that they couldn't be sure of support until after the bombing run.

A Victor with hoses deployed for refueling

Back at Ascension, the first group of Victors were returning. The island had only one runway and no taxiways, and the prevailing winds forced the Victors to land from the end opposite the hardstand. Under normal conditions, the plan would have been to land, taxi back along the runway to the hardstand, then land the next plane. This required the remaining planes to circle and wait, and the refuelings had drained their tanks too much for that to be possible. Instead, the Victors would simply wait at the far end until all four had landed, then turn and taxi back as a group. This meant that the last Victor down would be barreling towards the other three, and any brake failure would be utterly catastrophic, eliminating a sixth of the RAF's tanker force and imperiling the aircraft still in the air. But everything worked perfectly, and the runway was soon clear.

AN/TPS-43 radar

After the last refueling, XM607 dived to low altitude, hoping to sneak in under the coverage of the AN/TPS-43 radar at Port Stanley. 46 miles out, the Vulcan began to climb to the 10,000 ft chosen for the attack. Their target was the runway, in the hopes of disabling it and preventing the Argentinians from basing fast jets there. The altitude was partially to avoid AAA fire from the guns around Stanley, and partially to give the bombs enough speed to penetrate the runway. The British had calculated that the most effective way to make the attack was to come in at a 30° angle to the runway centerline, dropping the 21 1000 lb bombs at 50-yard intervals. This should give the antiquated radar and attack system a good chance of getting a hit on the runway.

Twin 35mm Oerlikon gun, used to defend Stanley

The actual attack was almost anticlimactic. Surprise and the efforts of the Air Electronics Officer9 meant that there was no gunfire or missiles to menace the bomber. The radar operator10 was able to pick up the required offset points11 with only minimal difficulty, and the bombs were released smoothly at about 0445 local time. Withers threw XM607 into a tight turn, and 20 seconds later, the bombs began their march across the airfield.

Damage dealt by Black Buck 1

In Port Stanley, about 7 miles away, the residents were awakened by the boomboomboomboom of the bombs going off. It was a tremendous morale boost, reassuring them that the British were on their way. A few minutes later, the AAA guns opened fire on the empty sky, as the Vulcan climbed for altitude. The crew transmitted the code word "superfuse" indicating that they believed they'd made a successful attack. Their first bomb had landed almost exactly in the center of the runway, while a second cratered the edge of the strip. Another bomb damaged a Pucara light attack aircraft and the only hangar on the field.

XM607 on display

The transmission allowed XL189 to break their radio silence, informing Ascension of their predicament. A tanker was dispatched, while XM607 headed for its last refueling, off the coast of Brazil. Withers described his first sight of the Victor as "the most beautiful sight in the world". Unfortunately for him, it didn't last long, as a leak in the refueling system resulted in a thin curtain of fuel covering the bomber's windshield when the probe was inserted. Fuel was still reaching the bomber, and out of fear of a problem with the equipment that would prevent reengagement, Withers remained in contact with the tanker, with one of his crew guiding him by looking through a small slit that was free of fuel. After that, it was a fairly simple four-hour cruise back to Ascension.

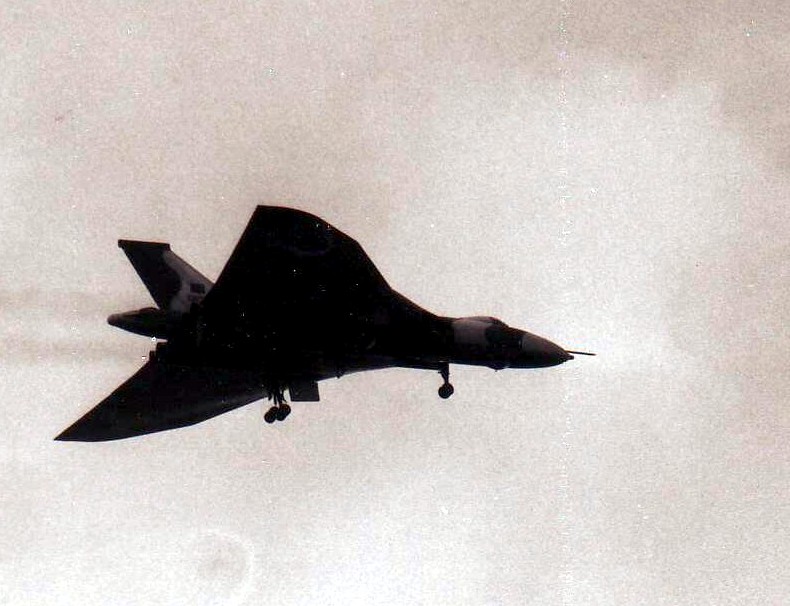

Vulcan landing at Ascension, May 1982

Black Buck was one of the most daring aerial missions ever attempted, and a tribute to the RAF. At the time, it was by far the longest-range bombing mission ever attempted.12 However, from an operational standpoint, it was a failure. A tremendous amount of time, effort, and fuel had been expended to place two bombs on the runway at Stanley, and the resulting holes were patched relatively quickly. There is more debate over the strategic effects of the raid. It's often credited with forcing the Argentinian Air Force to withdraw Mirage fighters from supporting the raids on the British ships and deploy to protect the mainland from similar raids, but the British quickly undercut any such effect when they promised they would do nothing of the sort. The fear of further such attacks did deter the deployment of fast jets to the airfield, which might have prevented the British gaining air superiority over the islands.

XM607 at RAF Waddington

Even as XM607 made the long trip back to Ascension, the carriers were launching their first raid on the islands.13 We'll pick up their story next time.

1 I've written a glossary to make it easier to keep track of terms in this series, and the full list of posts is here. ⇑

2 This aircraft was restored by Vulcan to the Sky, a private charity, and flown from 2007 to 2015. I deeply regret never getting to see her fly. ⇑

3 To put this into context, this is the distance from London to Karachi and back. ⇑

4 Actually, this wasn't directly driven by the needs of the Vulcans. Only a handful of Vulcans participated in those missions, which a consequently small number of probes. However, Vulcan probes were used as the basis for the refueling system hastily built and installed on RAF C-130s to give them the capability to airdrop urgent supplies and personnel to the Task Force from Ascension. Some of those missions lasted as much as 26 hours. ⇑

5 The Victor had originated as a contemporary of the Vulcan, part of the V-bomber force, and the 23-strong fleet were the RAF's only tankers. ⇑

6 Unfortunately for the crew of XM598, the aircraft was much too heavy to land and lacked any means to dump fuel. To get down to an acceptable landing weight, they had to spend several hours circling Ascension, stuck in the cold and noisy cabin. ⇑

7 Under normal circumstances, the reserve aircraft would turn for home when the primary aircraft had successfully completed its first aerial refueling. ⇑

8 I couldn't find any pictures of a Vulcan conducting a refueling, sadly. ⇑

9 British for the guy who runs the jammers. ⇑

10 Interestingly, the Vulcan's H2S radar was a version of the ones first used by the British in WWII. ⇑

11 Because the runway didn't show up that well on radar, the procedure was to lock the radar onto points a known distance and bearing from the target, and drop when they were in the right place. ⇑

12 Since then, the USAF has taken the record, flying B-52s and later B-2s from the Continental US to the Middle East. However, all of these missions involved the use of forward-based aerial tankers, which in my opinion leaves Black Buck still in a category of its own. ⇑

13 There were also more Black Buck missions, which I will cover much more briefly later on. ⇑

Comments

That refueling scheme blows my mind. War always comes down to math at some point, but it's all so naked in the Falklands War -- how far can we go, how far can they go, do we think they'll risk it, is it worth it for us to risk it -- it needs to be an Aaron Sorkin script or something. Great installment!

This entire epic has the continuing theme of - The British were 3 months away from getting rid of this aircraft - The British were in the process of selling off this aircraft - The British had already mothballed this ship, but it was not yet beyond recall - The British had already given all these guys notice, but they hadn't actually left yet so they could be kept on.

I get the strong impression that if the Argentinians had waited 6 months they'd have had a much better chance. And if they'd waited a year then they probably would have got away without a fight.

Of course, Argentina probably had its own problems, I have no idea if they COULD have waited.

Six months wasn't really possible because of weather. The South Atlantic is a truly nasty stretch of water, and the British were having to race the onset of winter with their counterattack. A year later, and the British have a much smaller chance of retaking the islands for obvious reasons, but the Junta needed a distraction immediately. As for why Argentina went ahead with enough time left on the clock for a counter, they were afraid the British had sent an SSN south, which basically could end an invasion single-handedly.

This may be an unpopular opinion, but I've always really loved the look of the Victor, especially from the front. Not beautiful, but somehow uniquely threatening.

I like the look of all the British planes from the V-bomber era. They've got a retro aesthetic to them that the USAF never quite nailed, although Sabres and B-47s come close.

They look their best in anti-flash white, though.

I'm assuming that the British had so few SSNs that publicly-available information gave them the confidence that the SSN(s) were someplace else when they did launch the invasion?

I think I've said this before, but I'm really enjoying (and learning a lot from) this series.

Yes, those V-bombers look like late 1940s Popular Mechanics illustrations of what "The Bomber of the Future" would look like.

Or for that matter, late 1980s Popular Mechanics when they were speculating about what Stealth would end up looking like.

@Directrix Gazer

I'm sort of with you on the Victor. It's definitely a striking airplane.

@Suvorov

Pretty much. They only had 12 in service at the time, which means probably 4 at sea on a regular basis. They're way too important and valuable to waste a quarter of the fleet in the South Atlantic without good reason.

On the mention of the C-130 resupply missions- some years ago I had the immense privilege of hearing Brigadier David Chaundler share his recollections of the war. He was a Lieutenant Colonel at the time and had flown out from England to take over command of 2 Para after their commanding officer, Lt Col H Jones, was killed at the Battle of Goose Green. Of course, at this point the only way for the British to get anyone to the Falklands faster than a ship was by parachute.

Apparently, the minimum speed of the Victor tankers was faster than the maximum level speed of a Hercules, so they had to refuel in a shallow dive. After a 14-hour flight, and pulling rank on the crew of the Hercules when they claimed conditions were too rough for him to jump, he parachuted into the sea wearing a survival suit. He was picked up by a boat from the nearby HMS Penelope (a Leander-class frigate), then taken by Penelope's helicopter to Invincible for a conference with Rear Admiral Woodward before being taken by another helicopter to his unit.

@AlphaGamma

Very neat. Unfortunately, I had to cut discussion of those because it simply didn't fit. I believe the max level speed/minimum speed problem was also true of the KC-97/B-47 combo (obviously, the tanker was slower there) so they also had to refuel in a dive.

I first remember seeing Vulkan as a movie star in "Thunderball". A gorgeous machine, and a perfect fit for a 007 movie.

Also, it kind of resembles a proto-Concord, which is always cool, although I suppose all of the aircraft with the delta wing kinda do.