From the earliest days of the Republic, America has been an advocate of the position that all ships should be able to sail the world's oceans freely for legitimate commerce, regardless of what any given government thought about it. This often brought it into conflict with other nations, ranging from the British and French, who both thought that interfering with shipping was a great idea in their efforts to defeat the other, to the Barbary States of North Africa, who thought that they deserved to get paid by anyone who didn't want their ship seized and their crew sold into slavery. As a result, the US fought an undeclared war with France and then a declared one with Tripoli over the matter.

Even while the nascent USN was fighting in the Mediterranean, the Napoleonic Wars were raging, and tensions between the Francophile Democratic-Republicans and the British began to grow. Some of this was because the Americans kept getting in the way of British plans to blockade Bonaparte into submission, but the biggest source of friction had to do with impressment. The American merchant fleet was a haven for sailors who had run from the Royal Navy, and British warships would frequently stop American merchantmen to search for deserters. Tensions were increased further because many of these deserters had taken American citizenship, which the British refused to recognize, although the Americans were most outraged by the occasional seizure of native citizens. The British offered to end the process, but only in exchange for American recognition of their right to full control over the waters around Britain, which was a price too steep for the US to consider.

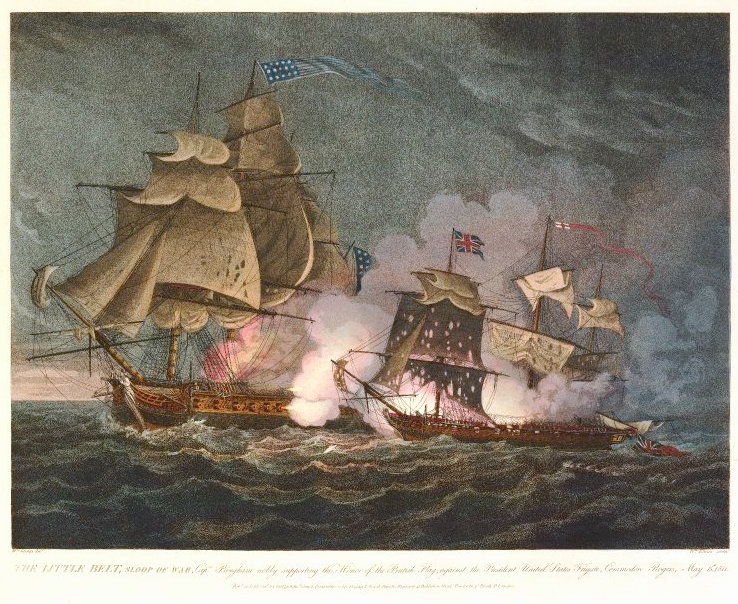

Matters came to a head in 1807, when the frigate USS Chesapeake departed Norfolk for the Mediterranean, and encountered HMS Leopard, a 50-gun fourth rate with orders to search American ships for British deserters. Leopard ordered Chesapeake to heave to for search, but the American warship declined, and Leopard opened fire on the unprepared frigate. Four of Chesapeake's crew were killed and 17 wounded before her captain struck the colors, and a quartet of deserters were removed from the American ship, which turned for home. The American public was outraged, and Jefferson, seeking to avoid a war, instead embargoed all American trade with everybody. Quite how he thought this would work is unclear, but in any event, it didn't, instead causing minimal inconvenience to Britain (whose trade shifted to South America) while devastating the American economy. Several subsequent attempts also failed, and in at least once case significantly increased tension with Britain. Then, in 1811, HMS Guerriere boarded USS Spitfire and carried off her Maine-born apprentice sailing master, prompting the US government to send USS President in pursuit. President, one of the big 44-gun frigates, found the British sloop Little Belt and demanded she identify herself. It's not clear who opened fire first, but when the smoke cleared, the much smaller British ship had suffered 11 dead and 21 wounded, while President was barely damaged.

President and Little Belt

By this point, mutual outrages had reached the point where war was probably inevitable, but diplomacy ran slower in the early 19th century, and it wasn't until the next year that Congress to finally got around to starting the War of 1812.1 A full recounting of the war is out of scope here,2 but the two sides fought each other to a draw, and with Napoleon's defeat in mid-1814, the British, no longer needing to control the seas and with a population tired of war, negotiated a treaty returning things to the status quo.

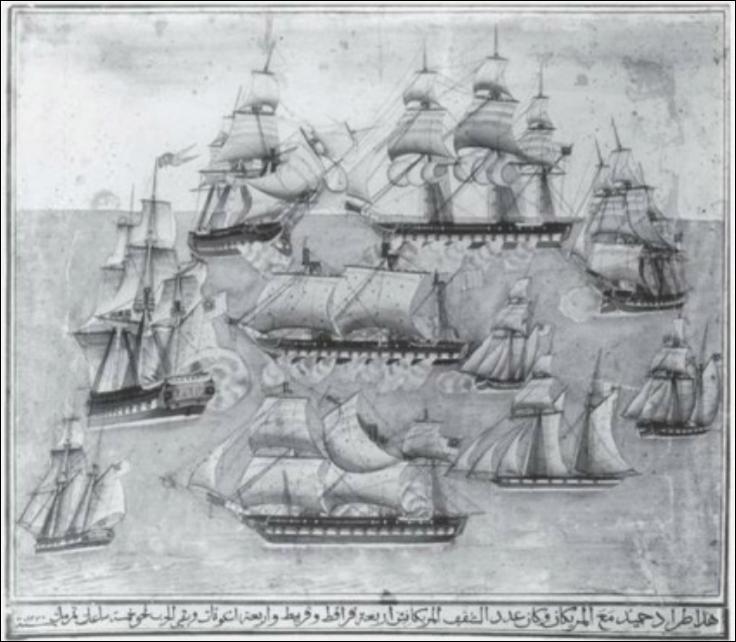

No sooner was the treaty signed than the Americans had to deal with the Barbary threat again. The ruler of Algiers had started seizing American ships even before Jefferson left office in 1809, but the situation with Britain had kept the US distracted. In 1812, he expelled the American consul and broke off relations, but the British blockade meant that American merchant ships were rare in the Mediterranean, so things slept until the peace treaty was signed. A week after it was ratified, President Madison requested a declaration of war on Algiers from Congress. Congress swiftly complied, and by May of 1815, Decatur was leaving New York with a force of three frigates and a number of smaller ships. They passed Gibraltar on June 15th, and two days later encountered the Algerian frigate Mashouda. The Americans swiftly gained the upper hand, capturing the Algerian vessel and 406 prisoners at the cost of only a single man killed. On the 19th, they ran into the brig Estedio, driving her ashore and capturing her crew.

Mashouda overtaken by the American squadron

With this background, Decatur arrived off Algiers on the 28th, and sent a letter to the ruler declaring that the US would pay no tribute and demanding most-favored-nation status. Talks began aboard his flagship two days later, and Decatur was able to give his nation a birthday present a day early when Algiers agreed to his terms. He spent the next month touring the other Barbary states, getting similar terms from Tunis and Tripoli before heading home a hero. It was the beginning of the end for the Barbary pirates, who were becoming increasingly outmatched as warships grew larger and more powerful. The next year, Britain got similar treaties out of Tunis and Tripoli, while Algeria again proved recalcitrant. The matter was settled by the RN, who bombarded the port and got him to sign a treaty ending slavery of Europeans.

The British bombard Algiers

The end of the Napoleonic Wars allowed the British to resume their normal pro-trade stance, and the Royal Navy ensured that for the rest of the century, merchant vessels could move more or less as they liked. But freedom of navigation was hardly dead as a matter of American policy. During WWI, both sides interfered greatly with merchant shipping, and for the first few years of the war, it was not entirely clear who more annoyed the Americans. The 1916 Naval Program was aimed at ensuring American ability to contest control of the seas with whoever won, Britain or Germany, although in the end it was the German policy of shooting at merchant ships without warning, and not the British policy of ordering them about and stopping trade with Germany that would irritate the Americans into entering the war. This process was repeated the next time around, although with somewhat less sympathy for the Germans, and during the Cold War, the USN repeatedly intervened in places like Libya and the Persian Gulf to ensure peaceful use of the sea for all. Today, we continue to enforce this policy, sailing warships through waters claimed by China3 and bombing those stupid enough to lob missiles at merchant ships. Given the benefits that oceanic trade has brought to the world, this has to count as not only our oldest but also one of our best policies.

Comments

I feel like there should also be a line or two about their overlord becomeing sicker and less able to provide credable protection.

PRESIDENT was commanded by John Rodgers, one of the most thoroughly unpleasant men to ever command a ship of the US Navy. He was also a ruthless combat commander, and he was bound and determined to avenge CHESAPEAKE - and by God, he did. Rodgers claimed that he didn't realize that LITTLE BELT was a much smaller vessel until the fight was over, which would require Rodgers to be blind, stupid, or both.