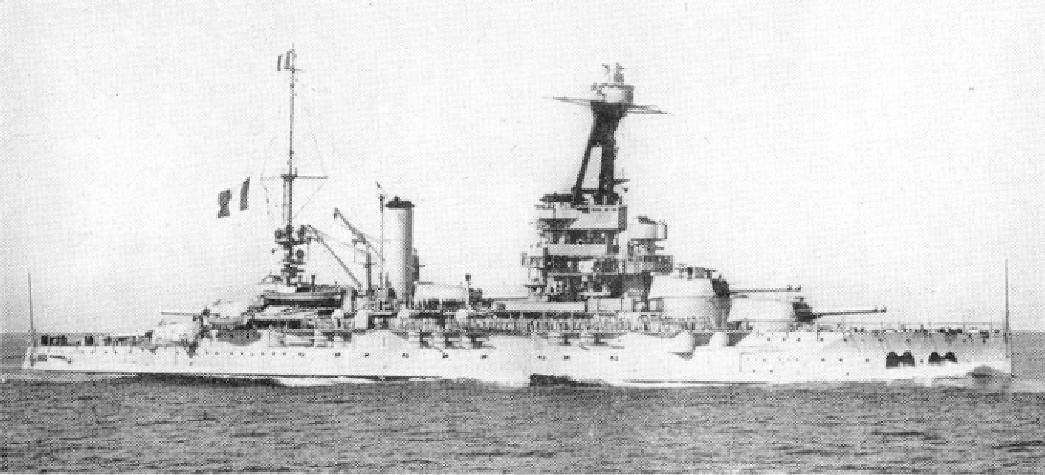

At the start of WWII, France was among the second rank of the world's major naval powers. Their dreadnought construction program had been interrupted by the outbreak of WWI, leaving them with five pre-1914 battleships, two Courbets and three Bretagnes. The Courbets were the first French dreadnoughts, and by 1939, both had been relegated to training duties.1 In front-line service, the Bretagnes were joined by the two ships of the Dunkerque class, the only small battleships built under the Washington Naval Treaty. They displaced only 26,500 tons standard, well under the 35,000 ton treaty limit, and were designed to hunt the German Deutschland class panzerschiffe.2 Two more battleships of the Richelieu class, built to the full treaty limit with two 15" quad turrets forward, were nearing completion.3 They had been laid down to counter the Italian Littorios, and another pair, counters to Bismarck and Tirpitz, had been authorized in 1938, although only one was laid down before the outbreak of war, and both were suspended in favor of more urgent projects.4

Dunkerque

In the early months of the war, the Marine Nationale cooperated closely with the RN, dispatching its battleships to hunt German raiders and protect transatlantic convoys. In mid-1940, as the risk of Italy entering the war grew, the Dunkerques and Bretagnes were dispatched to the Mediterranean as a deterrent, operating out of Mers-el-Kebir, in modern Algeria. Unfortunately, they could do nothing in the face of the disaster that overtook France in June 1940, also drawing Italy into the war. Courbet and Paris, stationed at Cherbourg and Le Havre respectively, provided artillery support to the defenders of those cities when the Germans approached, but ultimately were forced to evacuate to Britain in late June. Richelieu, officially completed the day after Paris fell, was sent to Dakar, in West Africa, to keep her under French control and give the French government leverage over the Germans. Richelieu's sister Jean Bart, launched in early May, was hastily made ready for sea and escaped only hours ahead of the Germans, then headed straight for Casablanca with only a handful of AA guns operative. Ultimately, the Armistice signed between Germany and France on June 22nd left the French in control of their fleet,5 but stipulated that they must be returned to their home ports, many of which were in the German-occupied zone.6

Provence

This posed a serious problem for the British. The addition of the Italian fleet to Axis naval power had already stretched their resources to the breaking point, and the addition of the French ships would make their position completely untenable. Churchill thus ordered that all French ships within the reach of the British be neutralized, either peacefully or by force, on July 3rd, 1940. Lorraine, one of the Bretagnes, was in the British-controlled port of Alexandria, Egypt, and she and her consorts were neutralized by local agreement. Courbet and Paris, in British ports, were seized by boarding parties. But the real problem were the four battleships at Mers-el-Kebir.

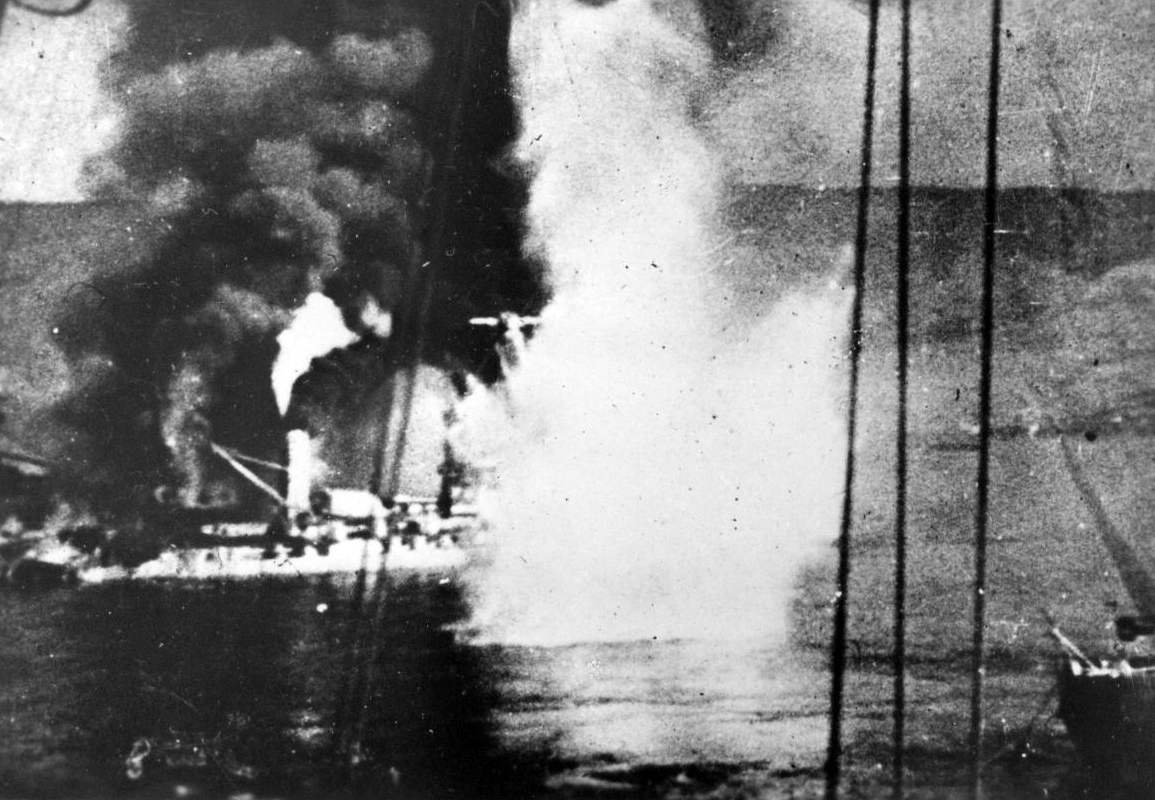

Strasbourg makes her break for freedom

Force H, built around battlecruiser Hood, battleships Valiant and Resolution and carrier Ark Royal, was dispatched with an ultimatum to the French. Either rejoin the fight against Hitler, be interned somewhere well out of his reach, or be destroyed. The French played for time, but the British eventually opened fire, while the French ships attempted to make for the open sea. Only Strasbourg, sister to Dunkerque made it, getting away with only minor damage. Bretange was hit early, with the shells setting off a magazine explosion which took the ship to the bottom within 10 minutes and carrying over 1,000 of her crew. Her sister Provence was hit only once, but had to flood her magazines and ran aground in the harbor. Dunkerque took four hits, the first pair disabling two of her guns and the steering, while the second pair wrecked her engineering spaces. She was quickly beached to stop her sinking. Strasbourg was chased by the British and evaded several air attacks, eventually making Toulon on the 4th, to the jubilation of the French. The attack had failed at its main purpose, and had greatly strained Anglo-French relations, with long-term consequences.

Bretange burns at Mers-el-Kebir

The British still considered Dunkerque a threat, and three days after the initial attack, a dozen Swordfish torpedo bombers were launched to take her out. None of them hit the battleship directly, but one sunk a patrol boat moored alongside, and her depth charges went off, blowing a massive hole in Dunkerque's side. The damage kept her immobile for 20 months while repairs were carried out, although she did eventually reach Toulon.

Richelieu at Dakar

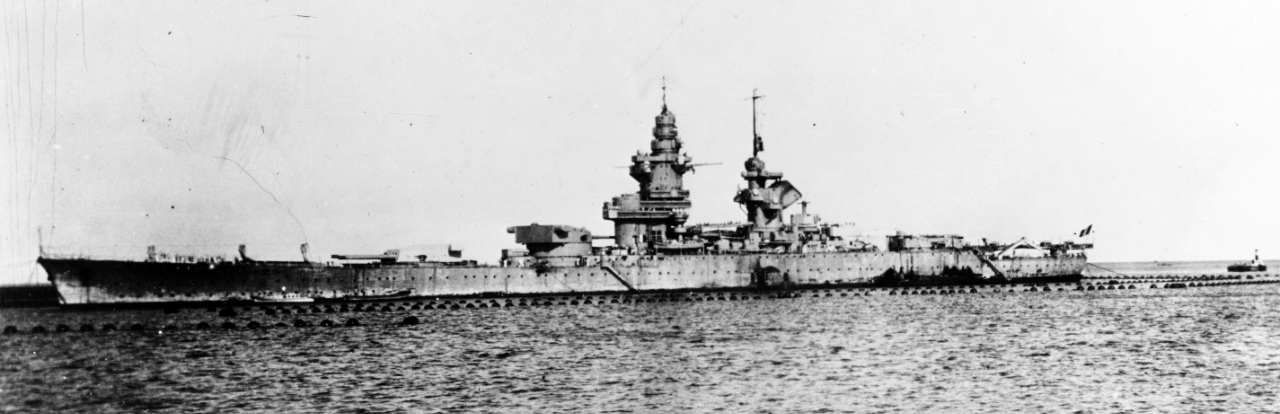

This just left Richelieu at Dakar, which would also be dealt with by Swordfish, this time flying from Hermes after the French in Senegal refused an ultimatum similar to the one given at Mers-el-Kebir. Five of the six torpedoes missed, but the one that hit did substantial damage. The result was a standoff which lasted until late September, when the British and Free French under Charles de Gaul attempted to seize Dakar. The Vichy defenders beat them off, and Richelieu, though immobilized and forced to use propellant charges intended for Strasbourg, dueled British battleships Barham and Resolution, although she scored no hits.

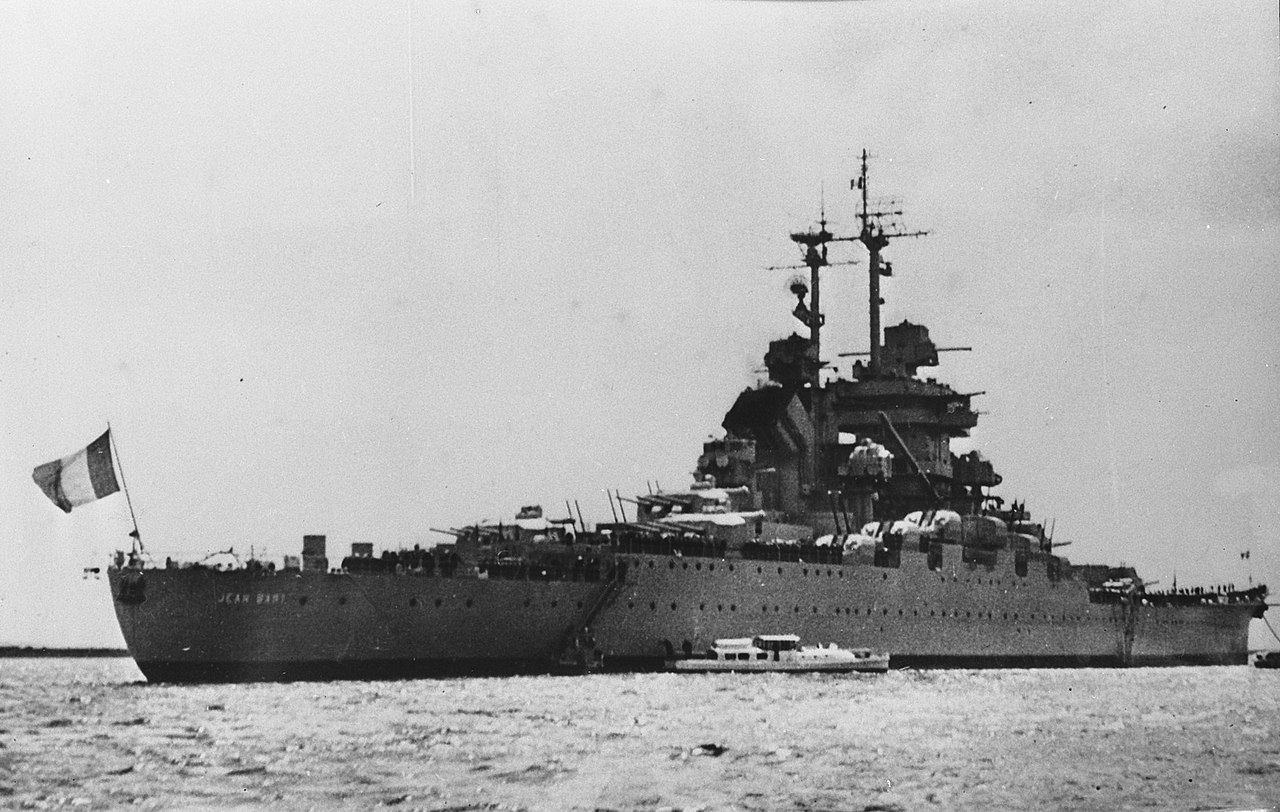

Jean Bart in Casablanca Harbor

The situation remained static for the next two years, with the French maintaining a wary neutrality and trying to rebuild their battered fleet. But on November 8th, 1942, Allied ships appeared off French North Africa from Casablanca to Oran and began to land troops, hoping to bring the French to their side peacefully. The French were unwilling to cooperate, and among their defenses was Jean Bart, still at Casablanca. She was still mostly incomplete, but the forward turret had been made operational, and she dueled USS Massachusetts, although her improvised fire control meant she scored no hits while the American ship made six. Despite this, she was not badly damaged, and she engaged the cruiser Augusta two days later, before being sunk in the shallow harbor by dive bombers.

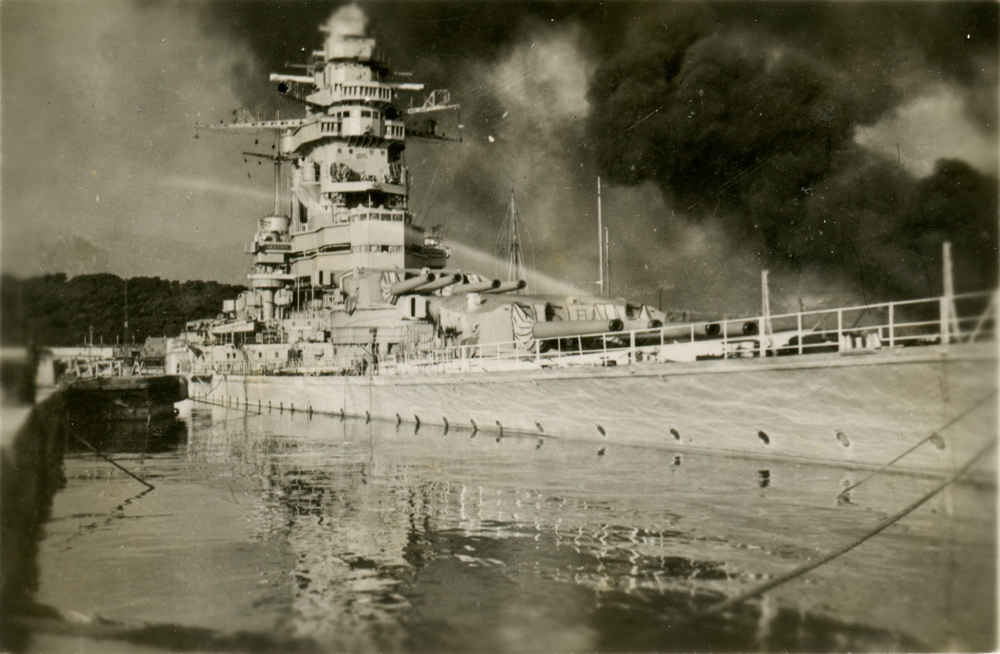

Strasbourg burns at Toulon

The invasion of North Africa had consequences for French possessions worldwide. Admiral Darlan, chief of the French Navy, agreed to surrender France's overseas possessions on November 14th, including Dakar, bringing Richelieu onto the Allied side. Two weeks later, Hitler ordered the seizure of the remaining bits of unoccupied mainland France, including the naval base at Toulon. Instead of letting their fleet fall into German hands, the French carried out their promise to scuttle the fleet, and while their sentries delayed the German troops by asking for paperwork, charges were set to make sure that the ships would be of no use to anyone. Strasbourg and Dunkerque were total losses, while Provence's officers delayed the Germans with small talk until her sinking was inevitable. 74 other vessels were also destroyed, and Churchill's nightmare was prevented from coming to pass.

Richelieu after her refit

The Allies now had five of the French battleships on their side, although only Richelieu and Lorraine were fit for combat. Jean Bart was too incomplete to be worth much during the war, except as a source of parts for her sister, who was sent to Brooklyn to repair the remaining damage and improve her light AA battery. After the overhaul was complete, Richelieu spent a few months with the British Home Fleet before being dispatched to the Far East in early 1944. There, she participated in a number of raids by the British fleet in the Indian Ocean, mostly intended to keep the Japanese distracted from American operations in the Pacific. Most of the time, this was simply screening carriers, but on a few occasions, she was able to join in on bombardments of land targets. She remained with the Eastern Fleet for the duration of the war, with the exception of a few visits to the shipyard for maintenance.

A Mulberry off the Normandy beaches

Of the older battleships, Courbet and Paris, captured by the British, had been stripped of their armament and used for a variety of roles ranging from AA platforms to accommodations ships and targets. Courbet would be the first to return to France when she was scuttled off the Normandy beaches as part of the Mulberry artificial harbor. Lorraine played a more direct part in the liberation of her homeland, providing fire support for the invasion of Southern France in August 1944. There, she dueled the turrets of her sister Provence, salvaged by the Germans and installed ashore to command Toulon harbor. The Allies were forced to devote significant firepower to suppressing them for over a week, with Lorraine herself drawing the last shell from them.

Jean Bart, completed postwar

Of all the battleships that fought in WWII, those of France had easily the wildest ride. Caught up in the disaster that overtook their nation in 1940, they were to play an outsize role in the complex web of politics that resulted. They were attacked by erstwile allies, scuttled, salvaged, and ultimately played a significant part in the liberation of their homeland, and the defeat of the Japanese in the Pacific.

1 A third was hulked in 1936, and was serving as a school ship in Toulon. She was later used for weapons trials by the Germans. ⇑

2 These were the famous "Pocket Battleships", essentially heavy cruisers armed with 6 11" guns and intended for commerce raiding. There was a great deal of panic in the world's navies when they were first built, but in practice, they were not particularly effective. ⇑

3 Interestingly, construction of these ships was in violation of the Washington and First London Treaties, which had limited France to 70,000 tons of new battleships before 1937, tonnage mostly used by the Dunkerques. France responded to British protests by pointing to the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, which allowed Hitler to build battleships. ⇑

4 One ship, Clemenceau, was a near-sister to Richelieu with her secondary battery rearranged to give more AA firepower. The other, Gascogne , was a related design that abandoned the all-forward armament in favor of one turret forward and another aft. The French considered her the lead ship of a new class, but she's classified with the Richelieus in most references, probably just for bookkeeping purposes. ⇑

5 This was actually a critical point in the Armistice, and the French would have fought on if the fleet had been demanded. Even if they'd given in, the Navy had plans to flee to British ports. ⇑

6 The French objected to this in Armistice negotiations, and while the Germans refused to change the text of the agreement, they tacitly accepted that the ships based in Brest, including the modern battleships, would in fact remain in Africa. ⇑

Comments

I was vaguely aware of some of that, but not in nearly as much detail.

It sounds to me as though France (at least the navy, early in the war) did not really view German occupation as permanent or intolerable. It's hard to make sense of their actions from the perspective of Axis vs Allies, but if you look at them as a third party trying to maintain an independent policy in the face of pressure, their actions seem much more logical. Or at least trying to maintain as much independence as they can get away with, expecting to renegotiate later. What do people think, is that accurate?

It's a paradigm that fits post-war actions too, particularly De Gaulle's * efforts to not be subsumed by NATO. It's a very different way to think compared to a US History perspective of with us or against us, but I can't say it's entirely wrong - France has had to make compromises but they have maintained independence. It's hard to believe that would have been true if the Nazis/Soviets had won, but maybe that's an American bias.

I was surprised something that fundamental could be changed as a modification.

Did Europeans not feel the need to make the jump to 16" guns? Or was there something complicated going on with treaty that I'm not remembering?

@David

Exactly. The French didn’t know the final outcome, and presumably thought that they’d be better off hedging their bets in case Germany won. This is against a background of 1918 and particularly 1870, where the losing power isn’t dismembered, even if they do have to give the winner a bunch of land and money. Also, the French in particular have always been very into their independence. For instance, their nuclear force and fighter programs.

@echo

Yes and no. There was likely to be a lot of commonality. Same engines, same general armor layout, similar hull form, same turrets, etc. But it was a fundamentally different design. I suspect a lot of the classification stems from the final outcome. Because the ship didn’t get very far, and there’s not a lot of information available, it’s easier to classify her as a footnote to the Richelieu article than to give her a grossly disproportionate amount of space. When writing, I was thinking about other things (naval diplomacy, mostly) and didn’t question it. The French did apparently consider her a new class, breaking from the naming tradition of the first three ships to instead be named after a province. I've edited the footnote slightly. Might take a closer look at French battleships in the future. I have good references there.

As for the 16″, it wasn’t a treaty matter. Developing guns and turrets is expensive and time-consuming (unless you’re the US, apparently) and 15″ is pretty close to optimum for a 35,000 ton ship, unless you have the wizards who gave us the SoDak.

I think they chose to hold on their fleet because it was valuable to Germany - even the existence of Vichy France wasn't at all assured. Anything was valuable that they could use to negotiate for a better position than that of a German province.

Also, the strategic situation at the time was very uncertain. After the Fall of France and before Barbarossa and Pearl Harbor, WW2 was essentially Germany and Italy vs Britain, and Churchill's back was against the wall. Even in '42, the US was just holding on in the Pacific and the Germans were still gaining territory against the Russians.

Then in November '42 Torch hits North Africa and the French have to decide who will win the war. Not an easy call.

I am a little hazy on my international law, but wasn't Mers-el-Kebir an act of war by Britain against France?

@Bobbert If it wasn't, the US response to the Japanese attack on Pearl harbor seems excessive.

@Bobbert

Yes, it was. The French chose not to declare war because it wouldn't have worked out well for them. They had a bunch of colonies that they figured were better protected by neutrality, because the British didn't really want a full-scale war with France either.

@Alexander

Well done.

One bit about the British attack on French ships that I find rather astonishing is that it happened only a couple weeks after a very serious proposal for a permanent union of the United Kingdom and France. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franco-BritishUnion#WorldWarII(1940) In the span of only a couple weeks, the Brits went from suggesting a permanent, irrevocable merger of their countries, to a pretty blatant act of war. And the really freaky part is that I think Churchill was probably right on both counts.

The spring of 1940 was completely insane.

Right, I screwed up my links last time too.

Franco-British Union. Or just scroll down to the WW2 section: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franco-British_Union (two underscores in the text seems to trigger italics in Markdown, so the article link with only one ought to work?)

It seems those are both attempts at the same thing: Keeping whatever can be saved from the debacle of the blitzkrieg in the war, or failing that, out of Nazi hands. "Mobilise all forces that can be mobilised, neutralise all forces that can be neutralised, destroy all forces that can be destroyed". If the French weren't going to stay in the war, i.e. be mobilised... then they would have to be neutralised or destroyed.

Yup. Like I said, I think Churchill was right on both counts. It's just weird that the right course of action changed so wildly in two weeks. I'm used to seeing that kind of story in schlocky fiction, not real history.