At the end of WWI, the Royal Navy faced a crisis. During the war, it had suspended new capital ship construction except for a handful of battlecruisers, while the American and Japanese building programs had continued to churn out ships that were more modern than the bulk of the British fleet. Worse, the British battlefleet had seen hard war service, and many of the early dreadnoughts were in bad shape and essentially unfit for further service. New battleships would be needed, ships that fully reflected the lessons of the war.

HMS Nelson

The most important of these was the need for an all-or-nothing armor scheme, as developed in the US. The war had seen major improvements in armor-piercing shells, and protecting against them required significantly more armor than previous vessels had. However, the increase in battle ranges gave designers a way out. Previously, the size of citadels had been set by the need to preserve stability and buoyancy if the ends were riddled. At long range, the many hits necessary to riddle the ends would not happen, and the citadel could be shrunk to thicken the armor.1 The British also looked to improve on the 15" gun due to the proliferation of 16" weapons in the American and Japanese navies. They investigated the triple turret, abandoned a decade earlier amid fears of increased mechanical complexity, and the 18" gun under the cover name of 15"/B.

Nelson in 1931

Two parallel design series were started, one for battleships, the other for battlecruisers.2 As this series was developed, the designers saw a serious problem with the battlecruisers. The boiler uptakes would leave large holes in the armored deck, and if the ship was headed towards the enemy, shells might be able to pass through the holes and into the aft magazines. The solution was to move all three turrets forward of the engines, on the basis of war experience showing that ships rarely if ever engaged targets directly aft.

The G3 battlecruiser3

The final design, the G3 battlecruiser, was a massive ship of 48,000 tons, about 15% more than Hood, armed with 9 16"/50 guns and capable of 32 kts. Even larger designs with 18" guns were considered, but the need to dock the ship for maintenance prohibited their construction. All three turrets were forward of the engines, with a new hexagonal superstructure between the second and third turrets. This superstructure was intended to support the new and very heavy Director Control Tower the British were developing to improve the accuracy of their fire. But by far the most interesting feature of the design was the armor layout. After Jutland, the British were understandably paranoid about the safety of their magazines. These thus received heavy armor, an 8" deck and 14" sloped belt, while the machinery was protected by only a 4" deck and 12" belt.4

HMS Rodney, sister ship to Nelson

Four ships of this design were ordered in October 1921, essentially as a backup plan in case the negotiations about to begin in Washington fell through. The talks proved successful, and the ships were suspended a month later before any serious work was done on them and cancelled in February 1922.5 However, the treaty negotiations resulted in the British being allowed to build two new battleships under the limitations agreed in Washington.6

Nelson

The design process for the ships that became the Nelson class was unlike any previous warship. For the first time, designers were working under a hard constraint on displacement, which they needed to approach as closely as possible to gain the maximum possible combat power. During the treaty negotiations, the British had investigated what could be done within the allowed limits, for both battleships and battlecruisers, but once the treaty was signed, the decision to build battleships followed swiftly. Speed was set at 23 kts, and the armament was to be three triple 16" turrets. All three turrets were moved forward of the superstructure, bringing them as close together as possible and reducing the size of the heavy magazine even more.7 Uniquely among British dreadnoughts, the Nelsons had only two shafts, and the engines were placed forward of the boilers to keep the superstructure free of smoke and the holes in the deck for the uptakes as far from the magazines as possible.

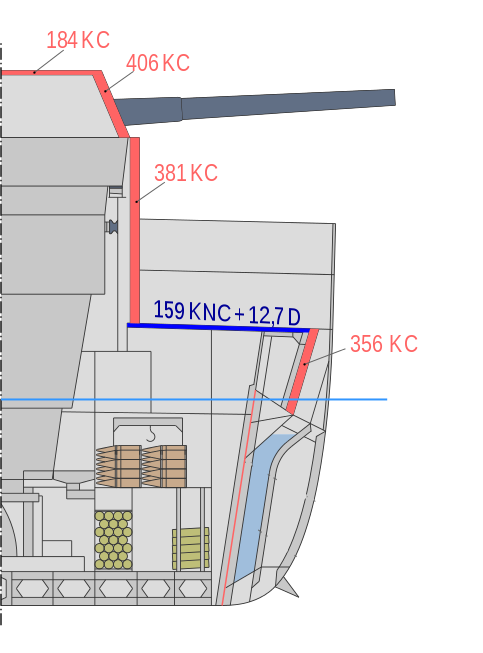

Other departures from normal practice were made to save weight. The hull was made deeper,8 which in turn reduced stresses and allowed the structure to be lighter.9 This also increased the volume available for the crew, improving habitability. Higher-strength steel and new structural practices were introduced to save even more weight, and great care was taken over details of the design that had previously been neglected. Many interior fittings were aluminum,10 and the deck was covered with Douglas fir instead of the traditional teak to save weight. The armor scheme was very similar to the G3, with a 14" internal belt over the magazines and 13" over the machinery, both inclined 18° from vertical. The deck was 6.75" over the magazine and 4.75" aft. Underwater protection was provided by a water-filled space inboard of a void, which was designed to protect against a 750 lb charge.11

Nelson

The armament was a major departure from previous British practice. The 16"/45 guns were designed to fire a rather light projectile very fast, on the basis of inadequate trials that indicated that this would provide superior penetration on oblique impacts. In practice, this simply was not true, and the resulting weapons were only very slightly superior in armor penetration to the 15"/42 of previous classes, while suffering greatly in accuracy and barrel life. A reduction of muzzle velocity mitigated these problems, but budget limits prevented the adoption of the heavier shells that would have been necessary to make the guns really satisfactory. The triple mounts were also a first for British battleships, and extensive safety measures were fitted as a result of the disaster at Jutland. These factors, combined with the drive for weight reductions, resulted in weapons that were initially unsatisfactory, although most of the bugs had been worked out by the start of WWII. Even then, it was slow to load, usually only able to fire about 1 round/gun/minute.12 The blast from these guns was ferocious, and they would do significant damage to the ship if fired abaft the beam. This was probably exacerbated by the light construction of the ships.

The turrets of Nelson13

The secondary armament of these ships was also rather interesting. While they had separate 6" anti-destroyer and 4.7" anti-air batteries, they were the first battleships designed to carry significant light AA armament in the form of four pom-poms. Nelson and Rodney were also the last battleships designed with internal torpedo tubes, being fitted with unique 24.5" torpedoes. During her battle with Bismarck, Rodney fired eight, one of which probably hit,14 the only known case of one battleship torpedoing another.15 These weapons used air enriched in oxygen to give improved performance, serving as precursors to the famous Japanese Long Lance.

Because the G3 configuration had been kept under wraps, the unconventional arrangement in Nelson and Rodney came as a shock to almost everyone. The third turret, dubbed X,16 was nearly admidships, and their unique profile lead to them being dubbed Nelsol and Rodnol, after a class of fleet tankers with names ending in -ol. The bridge being so far aft meant that the ships maneuvered rather differently from other vessels, although once the crew was used to their quirks, they proved reasonably handy.

Rodney firing in support of the Normandy landings

Nelson and Rodney are fascinating ships. They were the first battleships to take into account all the lessons of the First World War, but built shortly after the war, instead of nearly two decades later. They served throughout World War II, and Rodney is best known for her part in sinking Bismarck. She and Nelson gave good service around the world, proving substantially more useful than the 15"-gunned ships, although they were little loved and both went to the scrapyard soon after the war.

1 This was a distinct contrast to American practice. The USN preserved the conventional design standards, requiring 60% of waterline length to be protected by the belt to preserve buoyancy and stability. When the US attempted to duplicate the Nelson design, they discovered that under their standards, the arrangement produced no weight savings. Calculations on the Nelsons themselves showed that stability would be essentially zero if everything outside the armor was riddled and the spaces outboard of the internal belt flooded, which was probably acceptable, given how badly things would have to go to get there. ⇑

2 As with Hood, these "battlecruisers" were fast battleships, very different from the lightly-armored early battlecruisers. The design series had begun with K for the battlecruisers and worked backwards to G, while the battleship series ran from L to N. G3 designated a ship with triple turrets, while designs like K2 had twin turrets. ⇑

3 Original art for this post by Lord Nelson, who is officially The Best. ⇑

4 I don't really understand why the deck was cut so much more heavily than the belt. Also, the deck over the magazines for the 6" secondary guns aft was thickened to 7". ⇑

5 The N3 battleships also planned would have been the same size and used the same arrangement, but more heavily armored, armed with 18" guns and with a speed of 23 kts. The plan was to order four of them in 1922, assuming the treaty negotiations failed. ⇑

6 The short version is that battleships were limited to 35,000 tons standard, with guns no larger than 16". Standard tonnage was a complicated measurement that bore only a loose resemblance to more conventional tonnage measurements. In practical terms, the Nelsons were about 10,000 tons lighter than the G3s. ⇑

7 The all-forward arrangement made the great disparity in armor much more effective. A conventionally-arranged ship would have needed to provide protection to the fore and aft magazines from a wide variety of angles, which would mean that a great deal of the deck would have to be heavy. Concentrating the armament reduced this a lot. ⇑

8 Naval architecture jargon for taller, in this case by a full deck. ⇑

9 The logic behind this is fairly obvious to anyone who remembers basic beam theory, assuming that the ship is a beam with a bending load. For those who forgot or never studied it, just trust me on this. ⇑

10 This is a fairly common practice in displacement-limited designs to this day. On the Nelsons it made sense, but most modern displacement limits are attempts to save cost, which makes it ironic when designers are forced to use more expensive solutions to save weight, and gives the people who set such limits what they deserve. ⇑

11 The British claimed that because the water was not part of the standard loadout, it did not count as part of treaty displacement, but attempted to conceal this dodge from other powers, most of whom noticed it on their own. Flooding the water voids added 2,870 tons of water, increased draft by 23" and cost about 1/3 of a knot. ⇑

12 More details on these mounts can be found in this NavWeps article. ⇑

13 The boxes atop the turrets are launchers for the short-lived unrotated projectile rockets. ⇑

14 While Bismarck's wreck has been found, the area where the torpedo hit is buried in the seafloor, preventing an inspection. ⇑

15 Several battleships and battlecruisers fired torpedoes at Jutland, although their targets are uncertain and none appear to have hit. ⇑

16 I'm not sure why X was chosen. Conventional British practice would have been to use Q for an amidships turret. ⇑

Comments

What does it mean for something to be "abaft the beam"? I'm guessing "abaft" means behind. But what is the "beam"?

Quanticle, I just looked this up. And I think I understand what I've read.

The beam was to the side of the ship, at 90 degrees to the fore/aft line. So 3 o'clock and 9 o'clock if that terminology is more familiar.

Abaft the beam was behind that. So in this case, firing the guns in any direction that is pointing to the rear of a straight broadside.

Doctorpat is correct. I really need to find and link a good naval glossary.

Nelson and Rodney were... interesting coughuglycough. IMHO, the biggest problem with the design is the rather shallow belt, an issue exacerbated by being sloped and internal. Tests on the HMS Emperor of India would cause the British not to repeat that feature.

Conversely, one big upside to the design I rarely see mentioned is that the all-forward arrangement of the main guns allows the ship to fire all main guns while presenting a horrific target angle to incoming fire, making the belt all the more difficult to penetrate.

I'm not sure the target angle argument is actually true. Looking at the drawings in Burt (easier than hunting down actual numbers), there's very little difference between the angle at which Nelson and Hood can bring all of their guns to bear forward. Yes, it was undoubtedly more comfortable to do on Nelson, but the reason nobody adopted high-angle tactics is that they also mean you're closing with the enemy fairly fast, which you may not actually want to do.

Nelson could bring all her guns to bear at 25 degrees AFAIK. Hood could theoretically come close with 300 degrees of train, but in practice at Denmark Strait, the rear guns didn’t fire until the angle opened up to ~56 degrees following a 20 degree turn per

http://www.hmshood.com/history/denmarkstrait/bonomi_denstrait2.htm

With respect to closing speed, it’s not always desirable to close rapidly, but it fits neatly with RN doctrine at the time (close the range down to 15k yards or less and hammer away.) Of course, even at top speed, Nelson would still need over 20 minutes to close from 30k to 15k yards, assuming the Germans stuck around (not likely), and I expect she could go slower if needed.

How quickly can they accelerate? Also, I assume there is some value in moving quickly in order to make targeting harder.

Though I also wonder if weaving is easier than slowing down in terms of reducing velocity made good?

RN doctrine at what time? Nelson's career spanned almost 20 years, and doctrine changed quite a bit over that period. And even when RN doctrine was to close to 15kyrd as quickly as they could, they then would presumably fight at that range. Which implies the 90 degree target angle everyone used for their battleships. (The US at least based cruisers on 60 deg.)

Also, note that the forward bulkhead on NelRod was 12"-8" NC. That would be a major weakness if charging towards the enemy was a significant part of the playbook. It's weaker than the belt, and in that case, more exposed.

As for the firing angle at Denmark Strait, note that shooting directly forward was never particularly comfortable for any battleship. The blast damage to the forecastle could be significant, and on Nelson it was made worse because of the light construction.

@redRover

Acceleration on a 35,000 ton ship was never particularly good. Weaving would work better, as it also messes with the enemy's fire control, makes you harder to hit with torpedoes, and at least with the systems Nelson had, can be dialed out of your own gunnery solution. But if you really want to slow your rate of closure, then just turn to open your broadside.

Re: acceleration...not well. High speeds / maneuvers can help throw off enemy targeting, but doesn’t do your own any favors either.

That appeared to be the doctrine leading up to the war and seems to have carried through at least the hunt for Bismarck. With better fire control radar that improved accuracy at longer ranges, I’m sure that changed over time.

Of course, I’m not saying to charge in head first at top speed either. Keeping the enemy 30-45 degrees off the bow, while slowly closing the range (if enemy permits) would suffice, and provide a tough angle of attack on both the belt and the bulkhead and a narrow target relative to broadside. While other ships could theoretically do it with extreme over the shoulder shots, as you said, Nelson could do it much more comfortably, and with more leeway given the angles available to the third turret vs rear turrets on conventional designs.

And no, I’m not suggesting Nelson could keep it up indefinitely, but probably long enough to land (and avoid) some heavy hits.

My biggest problem with this is that ships usually don't fight alone. If in practice NelRod can shoot at 30 deg off the bow, and it takes every other ship 40 deg for a full broadside, than unless the Admiral in command has only those two ships to worry about, he's just going to order 40 deg when he wants to open his broadside.

As for keeping the enemy 30-45 deg off the bow, I think "enemy permits" is doing a lot of the work there. Tactics have to be resistant to what the enemy wants to do, and they have to take into account not only what the enemy is doing right now but also what the situation will be later. Sure, if I was aiming at a stationary target I might do a spiral around him at 45 deg, but I wouldn't assume I could pull it off on a maneuvering target.

I think my biggest issue with this theory is that I don't think the British saw it that way, whatever the capability of the ship on paper. The weak forward bulkhead is pretty strong evidence of that.

That depends heavily on your fire-control system. The USN Mk 38/Mk 8 was essentially immune to own ship motion. I've cited Iowa's experience at Mili before, and I've also had reports of one ship doing back-to-back 720 deg turns that totally failed to phase the system. Nelson's wasn't that good, but it was an early AFCT, not a Dreyer Table, so it was at least synthetic.

Admittedly I’m thinking mostly of a small scale surface action vs being tied to a battle line.

Of course the “enemy permits” bit made it all but impossible in practice given that the Germans would actively avoid a slugging match with NelRod, which couldn’t meaningfully give chase. Still, if they did want to play, did it really involve anything more than turning the ship as needed to maintain the desired angle? Doesn’t seem like enemy movements would really require any hard maneuvers at the long to medium ranges I’m talking about.

I think this is a lot of the disconnect between us. Do you mind my asking if you're a World of Warships player? Because this matches what I've heard of tactics in that game. I come from the design history/technical side, where the focus is on battleships as fleet units.

It's not that the maneuvers would be complex so much as just "the enemy gets a vote". They're going to be working to their best tactics, which means either sitting at range or trying to close. And Nelson wasn't a fast ship by any means.

Never played World of Warships, though I’ve spent plenty of time fooling around with things like NAaB, examining armor schemes, etc. to try and gain some insights about these things.

Re: battleships as fleet units, that was certainly their raison d’etre, though I suppose I don’t give it as much consideration given the dearth of large scale surface engagements during WWII.

NAaB? Not sure what that is.

As for viewing battleships as fleet units, my take is basically that warships are best understood in the context in which they were designed. This is often different from how they were used, because most battleships were used in a very different context from their design, which was often a decade or more earlier.

NAaB: http://www.panzer-war.com/NAAB2.htm

"Of course, I’m not saying to charge in head first at top speed either. Keeping the enemy 30-45 degrees off the bow, while slowly closing the range"

Keeping the enemy battleships 30-45 degrees off the bow, means the enemy destroyers are going to be closing the range at about 1500 yards per minute. When they're at about 5000 yards and 90 degrees off your bow, your torpedo defense system is going to get a workout.

Assuming the enemy force has a host of destroyers and you don’t have a sufficient supporting cast, it’d certainly be unwise to engage. Of course, that tended to be a bigger problem for the Kriegsmarine than the Royal Navy (North Cape for example).

Destroyers aren't perfect, and a lot of battleship tactics involved not getting into torpedo range of the enemy force. I think John is right on this one.

The comments about the Nelson's fwd bulkhead being only 12'' upper and 8" lower is a vulnerability. That could be true if that amount of steel was the only metal to come into play. At 15K yards, Nathan Okun's armor penetration theories, indicate a considerable amount of shell deceleration/deflection would occur upon passing through several inches of deck and hull steel. The forward bulkhead though thinner may not be as vulnerable as believed. And if a more broadside hit were to occur, the 12"/8" forward bulkhead would easily deflect an incoming shell. The Iowas also had a relatively thinner bulkhead system so they seem to be in good company in that regard.