The following is from Jim Pobog, the tour department lead on the Iowa. He was a boiler technician on the oiler Mispillion off Vietnam, and has kindly given me permission to post some of his sea stories here. Here's one in honor of our recent discussions of engineering. Some of the terminology here is best understood after reading Propulsion Part 4.

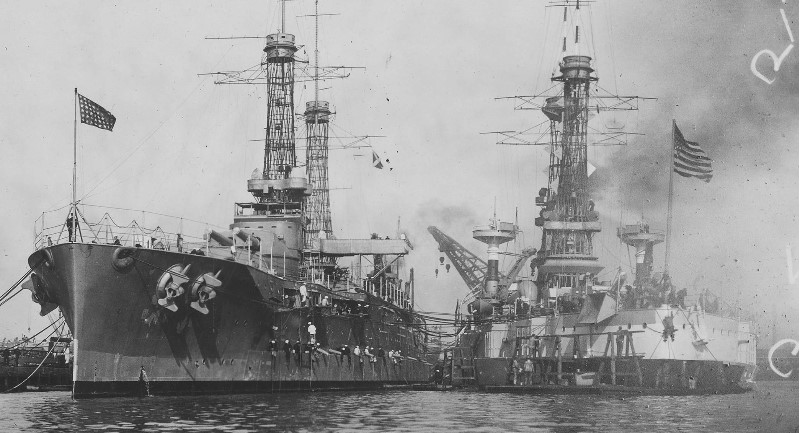

USS Mispillion (AO-105) off Vietnam

One of the interesting effects of being at sea for long periods of time was that it was easy to lose track of what day it was. The repeated routine day after day led you to doing things on sort of an autopilot, never expecting variation.

At one of these times I was on watch in the fire room in the middle of the night. We were just station keeping, sailing in those big circles, back and forth up and down the coast of North Vietnam.

Quite suddenly the engine-order telegraph rang. The engine-order telegraph is the thing you see in movies, the large dial that indicates what speed the Officer of The Deck wants the ship to go. We were cruising along at Ahead 1/3, then… RIIIING!!!! RIIIIING!!!, and it shows All Back Emergency.

Now that is a thrill, having those bells come out of nowhere in the middle of the night.

Recent Comments