After a hectic first month of combat, Iowa’s war slowed down. The second half of March and April were spent supporting the carrier groups, which at this point in the war were not facing a serious air threat. May 1st saw Iowa returning to action with the bombardment of Ponape Atoll, accompanied not only by New Jersey but also by Massachusetts, North Carolina, Alabama, and South Dakota. The Japanese were smart enough to keep their heads down this time, despite the extensive damage that was done to their infrastructure, primarily the island's three runways. After 70 minutes, the bombardment was terminated for lack of suitable targets.

Iowa firing her guns in the Pacific

The remainder of the month was a mix of time spent in anchorage and at sea training, before the action resumed in mid-June with the invasion of the Marianas. Iowa was again supporting the carrier fleet, although she and the other fast battleships were detached to bombard Japanese positions on Saipan and Tinian on June 12th in preparation for the landings beginning on the 15th. Iowa blew up an ammunition dump, which was apparently rather spectacular, but the ships were forced to remain far enough offshore that the bombardment was described as "a Navy-sponsored farm project that simultaneously plows the fields, prunes the trees, harvests the crops, and adds iron to the soil."1

Iowa bombarding targets on Tinian

The invasion of the Marianas drew out the Japanese for the first time in a year. On June 19th, the Japanese launched four major air raids from their carriers and bases ashore. Iowa had by now returned to the carriers, and she and the rest of the battle line were formed up between the carriers and the incoming Japanese forces. She shot down three planes, one Kate torpedo-bomber, one Lily light bomber, and one Zero (in combination with fighters), before the Japanese began to detour around the battle line to get at the carriers. This tactic ensured that for the rest of the war, the battleships fought antiaircraft actions close to the carriers. Over the course of the 19th and 20th, the Japanese lost approximately 600 airplanes and three carriers, leading to the action being dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, more memorable than the official Battle of the Philippine Sea.

Contrails during the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The rest of the summer passed uneventfully. Iowa remained in the Marianas and Marshalls, drilling the crew and protecting the carriers. In September, the US began preparations for the invasion of the Philippines, with Iowa supporting numerous carrier strikes. On October 1st, Iowa became press ship for the Third Fleet, responsible for transmitting news bulletins and wire photos back to shore facilities. The invasion of Leyte island, in the central Philippines, was scheduled for October 20th, and Admiral William "Bill" Halsey, commander of the Third Fleet, launched strikes on Okinawa and Formosa (Taiwan) to cover them. On October 14th, Iowa was again subject to air attack, shooting down a Judy dive-bomber.

Iowa (front right) in the lagoon of Majuro Atoll, 1944

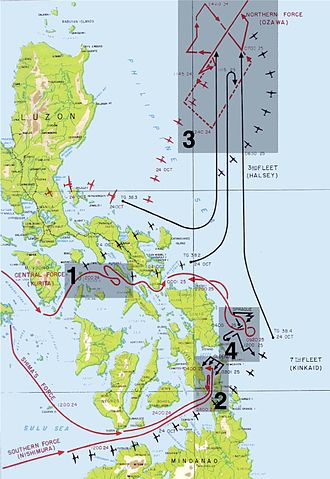

The Japanese had officially designated the upcoming battle as the Decisive Battle their doctrine called for. They had put together a complex plan, where the carrier groups would decoy the American carriers off,2 while their battleships would pass through the Philippines and fall on the invasion force from north and south. It didn't go to plan during the resulting Battle of Leyte Gulf. The US detected the Center Force (northern battleships), and carrier strikes sunk Musashi, sister to Yamato. Halsey interpreted this as a defeat of the Center Force, and when the Japanese carriers were detected, he took TF 38, the fast carrier task force, after them.3

As TF 38 headed north (the Center Force was coming from the west), the Battle of Suriago Strait was unfolding, the last clash of dreadnoughts. TF 38's battleships were detached during the night, and sent ahead, to try to bring the Japanese carriers to action after the air strikes had gone in. The air strikes proved effective, but less than an hour short of bringing the carriers into gun range, the battleships were ordered south again. Center Force had fallen on an escort carrier group designated Taffy 3, off Samar. Taffy 3 fought back in the finest action in the history of the US Navy, driving the Japanese off.5 While this action was still ongoing, Halsey turned south again, to try to either stop the Japanese, or catch them while they were retreating. Unfortunately, neither objective was achieved, although the earlier airstrikes had cost the Japanese four carriers.

USS Iowa, late 1944

Iowa remained in the waters around the Philippines through the first week of November, before retiring to Ulithi Atoll, which had become the main fleet anchorage. On November 25th, during air strikes on the Manila area, TF 38 was subject to intense kamikaze attack, and Iowa fought very well, taking out two Jill torpedo bombers and a Judy dive-bomber, and bringing her total score for the war to seven Japanese airplanes.

The next set of strikes on the unliberated areas of the Philippines brought an unpleasant surprise. On December 18th, TF 38 ran into Typhoon Cobra. Three destroyers capsized and sank, and most of the rest of the fleet was beaten up. Iowa lost one of her floatplanes over the side, and suffered extensive damage to 20mm mounts and deck fittings. Worse was yet to come. Five days later, a bearing on the number 3 shaft failed, leading to heavy vibration being felt as far forward as the bridge. She was detached from TF 38, and ordered back to Ulithi, where inspection revealed that she would need drydocking. This took place at Seadler Harbor, just north of New Guinea.

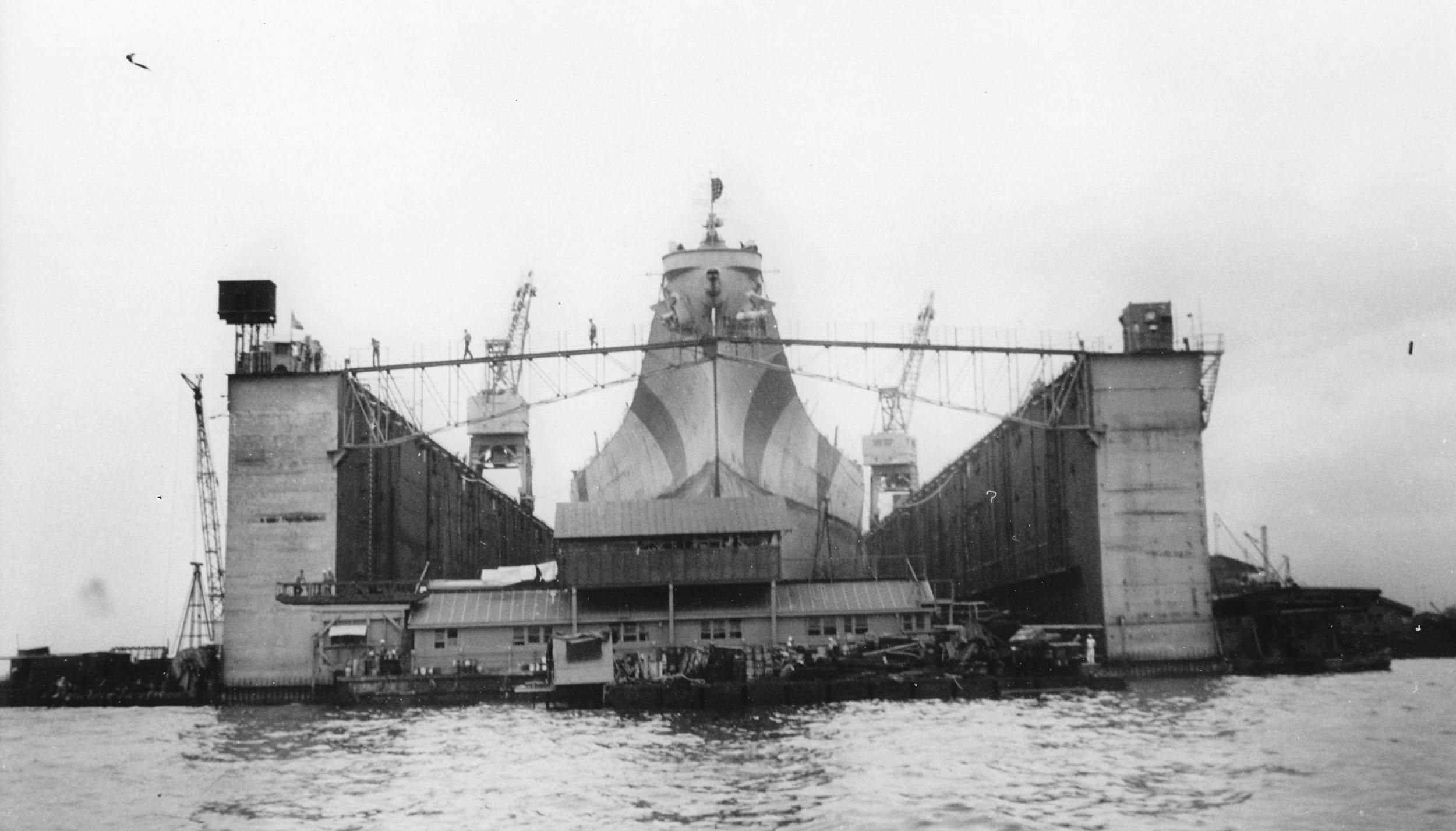

Iowa entering a floating drydock in Seadler Harbor, Admiralty Islands, Dec 27 1944

While entering the floating drydock, the Captain, Jimmy Holloway, brought the ship in at 4-5 kts, much faster than usual. The officer in charge of the drydock, R.K. James, asked him to slow, but he refused until Iowa was half way in, then ordered 'full speed astern'. Iowa "shook like a damned destroyer and stopped just where she should be", but in the process swept all of the docking blocks out of position, and James later discovered a streak of gray in his hair which he blamed on the incident.

Iowa drydocked, December 1944

Iowa was already due for an overhaul, having been at war for over a year, and the number 3 propeller was removed and secured on deck. She was ordered to Hunter's Point Navy Yard in San Francisco, which she reached on January 15th. By this point, Iowa had steamed over 100,000 nautical miles since arriving in the Pacific a year previously.

Massachusetts refuels a pair of Fletcher class destroyers6

One aspect that deserves to be mentioned is Iowa's role in refueling destroyers at sea. As she was designed with an endurance of 18,000 nautical miles at 12 knots, she had fuel to spare for the short-legged destroyers accompanying the fleet. Between July 1st and August 17th, 1945, for instance, Iowa fueled a total of 74 destroyers and transferred over 2,000,000 gallons of fuel oil.

Next time, we'll look at Iowa's refit, and the end of the war in the Pacific.

1 History of US Naval Operations in World War II Volume 8, pg 180 ⇑

2 They had no air groups to attack with after Philippine Sea. ⇑

3 At this point, we find the greatest what-if regarding the battleship in WW2, as Halsey made plans to detach his battle line to guard the route the Center Force took, but never executed them. I'm not going to go into detail here, as it deserves a full post of its own. ⇑

4 1 is the air attacks on the Japanese Center Force, 2 is Suriago Strait, 3 is the carrier attack on the Japanese carriers, and 4 is Samar. ⇑

5 One of our volunteers on the Iowa, Bob DeSpain, was on USS Hoel, one of the ships sunk that day. It was a great honor to get to know him, before he passed away in 2017. ⇑

6 I couldn't find any WWII photos of Iowa doing UNREP. But Massachusetts is an excellent ship, too. ⇑

Recent Comments