On September 20th, 1945, only a few days after the Japanese surrender, Iowa left Japanese waters, bound for Okinawa with 354 passengers, mostly liberated POWs. In Okinawa, she picked up another 562 passengers under the auspices of Operation Magic Carpet, the US effort to bring troops home as quickly as possible by packing them onto whatever ship was available. Most of the contingent from Okinawa were Seebees, who amused themselves by fighting one another. Iowa proceeded to Seattle, where she unloaded them and hosted over 10,000 visitors during the Fleet Week/Navy Day festivities.

Iowa and Maryland in Seattle for Navy Day 1945

Iowa spent the rest of the year in Southern California, training or undergoing refit. However, the demobilization in the wake of the end of the war badly affected her. She had lost so many people by November that her captain considered undermanning to be actively hazardous. She spent 3 months in Japan in early 1946, weathering more storms (as well as waves from an earthquake) when crossing the Pacific. The rest of 1946, as well as 1947 and 1948, was spent primarily training new sailors on the west coast, with an occasional trip to Hawaii. Iowa was decommissioned at San Francisco in March of 1949, a victim of the shrinking defense budgets of the era.1 Shortly before decommissioning, she flew off one of her floatplanes, the last-ever manned catapult launch from a battleship.

Iowa entering mothballs

But it was not to last. In June of 1950, the Korean War began. USS Missouri, the only remaining battleship in US service, rushed to provide support during the Inchon landings in September. She remained off of Korea until March, while New Jersey frantically recommissioned. New Jersey was followed into service, and on the gunline off Korea, by Wisconsin. Iowa was ordered back into service on July 14th, 1951, formally recommissioning on August 25th. Barely three weeks later, trials began, although she wasn't required off Korea until April, when she became the flagship of the 7th Fleet.2

Iowa off Korea

Iowa compiled an excellent record off Korea, regularly pounding rail targets, bridges, and enemy formations. This was a daily chore, unlike the bursts of action during WW2. At night, the 5" guns usually performed harassment fire, but occasionally the main battery joined in. The captain made sure to vary how and when, in an attempt to keep the enemy 'waiting for the other shoe to drop'. She was handicapped by a shortage of crew, most notably in engineering. Only half of the boilers could be manned under normal conditions, restricting her to 27 kts.

Iowa picked up another problem on May 20th when Admiral J. J. "Jocko" Clark took command of the 7th Fleet, and hoisted his flag on Iowa. Clark was an aviator, and wanted to be out with the carriers. However, he was unable to pull Iowa from bombardment duty. He did not like the shock he was subject to in his cabin when the forward turrets were fired, and ordered that only Turret 3 be used for bombardment, forcing the crew to shift the shells from the magazines of Turrets 1 and 2. On a more amusing note, when Iowa’s officers asked the commander of the 7th Fleet for a reduction in routine paperwork, he requested a separate report with specific recommendations. He also routinely hosted visitors, which meant that Iowa’s Captain rarely saw his in-port cabin.

Iowa firing at targets in North Korea

On May 25th, Iowa attacked Chongjin, a major North Korean industrial center only 55 miles from the Russian border. She did enormous damage during the 11 hours of the bombardment, including shelling a gas storage area which produced spectacular results. The Communists claimed to have sunk three ships, but Iowa and her escorting destroyers weren't even scratched.

Most of Iowa's tour was a fight between her guns and the North Korean repair crews. Destroyed railroad tunnels and bridges were found back in service in a matter of weeks, only to be destroyed again. Iowa did visit Chongjin a few more times, and even experimented with anchoring to improve accuracy. That was stopped when it was pointed out it made the ship very vulnerable to air or submarine attack. Her most frequent target was the port of Wonsan, which was bombarded at least dozen times.

Iowa anchored and firing at the North Korean coast

She finally returned home in October, after her last mission, providing 'pre-invasion bombardment' for a feint designed to draw North Korean and Chinese troops out of their bunkers. Missouri replaced her on the gunline, and New Jersey's second deployment closed out the Korean War. Iowa had fired more than 4,500 16" shells, twice as many as she had during the entirety of WW2.

Iowa was transferred to the Atlantic, where, after a refit, she spent the summer of 1953 on a midshipman training cruise to Edinburgh and Oslo, followed by a second deployment in the fall to participate in Operation Mariner, a NATO exercise involving Iowa, Wisconsin, and HMS Vanguard. She visited Portsmouth, Copenhagen, and Lisbon during this deployment.

Iowa spent 1954 steaming up and down the east coast on training duty, mostly between Virginia and Guantanamo Bay.3 Of note, on June 7th, all four Iowas operated together for their only time in their careers.

Iowa is the ship closest to the camera

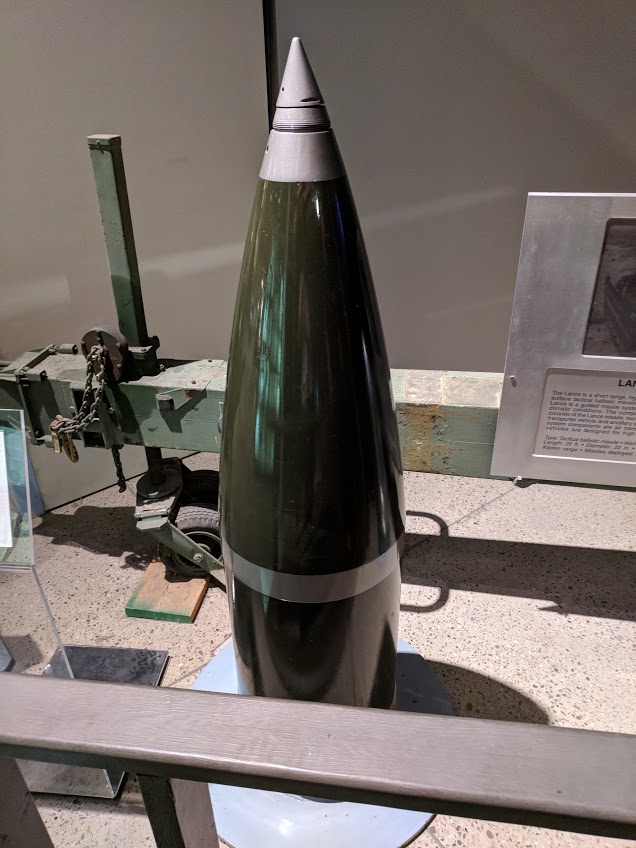

In January of 1955, Iowa became the first battleship assigned to the 6th (Mediterranean) Fleet since the end of World War II.4 She remained there until April, visiting Italy, France, Greece, Turkey, and returning to Algeria. A midshipman cruise a few months later saw her in Spain and Portsmouth, before a major refit in the second half of the year, including regunning. I believe that she was modified at this point to carry the Mk 23 nuclear 16" shell.

A Mk 23 at the National Atomic Museum5

1956 was more of the same, with a midshipman cruise to Denmark and the UK during the summer, and a special deployment to the 6th Fleet starting in January of 1957 because of the Suez Crisis. After three months in the Mediterranean, she took the traditional summer cruise, this time to Brazil. Upon her return, she departed for another NATO exercise, Operation Strikeback. The 300 participating ships made this the largest naval exercise since WW2.6

Iowa in 1957, shortly before decommissioning

Upon her return stateside, Iowa began the process of entering mothballs for a second time. She formally decommissioned on February 24th, 1958, in Philadelphia. Missouri and New Jersey had already deactivated, and Wisconsin followed 12 days later. For the first time since 1895, the US Navy had no battleships in commission.

Fortunately for Iowa and her sisters, the story of the battleship wasn't quite done. We'll discuss that next time.

1 Her daily running cost of $25,000 (approximately $250,000 today) was cited as a major factor. It's not widely remembered just how badly the US military was cut in the late 40s, but the situation was dire, prompting savage interservice battles. ⇑

2 The 7th Fleet has been the major US naval component in the Far East since 1945. Before that, it was the naval component in under MacArthur's command in the Southwest Pacific. ⇑

3 It was a major US naval base before it gained its current reputation. ⇑

4 Missouri was sent to the Med in 1946, although it appears that the 6th Fleet wasn't officially established until 1950, so this statement is only partially true. ⇑

5 Thanks to Andrew Hunter for the photo. Mine didn't turn out that well. ⇑

6 A parallel can be seen between this and the later exercises used so effectively by the Reagan Administration. ⇑

Iowa Part 5 – Korea and the 50s is up at Naval Gazing.

Also, I’ve decided to cut the Monday repost, at least for the time being. I may bring it back when I have something I want to get out quickly, but I’m starting to run a bit low on posts I can throw up without substantial updates.