After five very successful years in service during her third commission, tragedy struck Iowa. On April 19th, 1989, she was conducting gunnery drills as part of FLEETEX 3-89, a training exercise with the navies of Brazil and Venezuela. At 9:55, while the center gun of Turret II was being loaded with the first round, the powder exploded, killing 47 men. This exact cause is still somewhat controversial, and the Navy's handling of the investigation did not help. I should emphasize at this point that everything which follows is my own opinion, and I don't speak for anyone else on this.

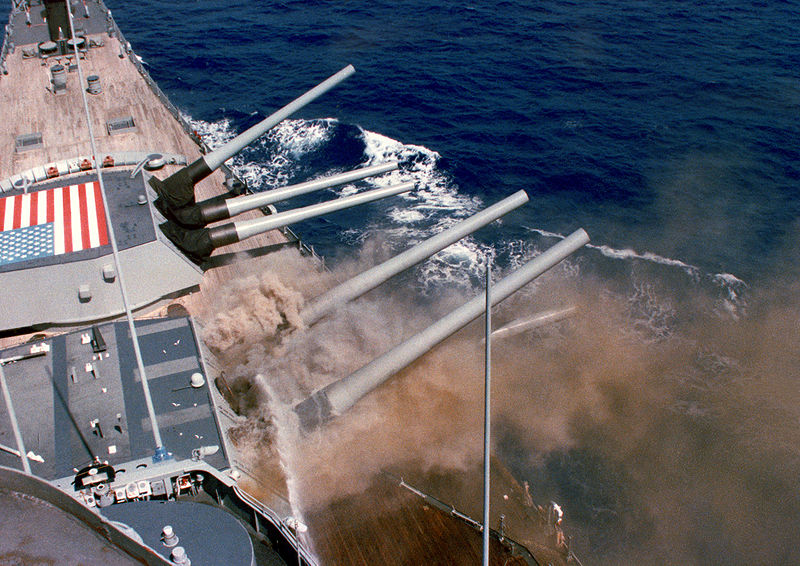

Smoke billows from Turret II after the explosion

In the immediate aftermath, the crew of the Iowa responded heroically, fighting to save the ship in what was still a very dangerous situation. The anti-flash measures, most notably the scuttles isolating the powder flat from the turret proper,1 worked well, and a repeat of the fate of the battlecruisers at Jutland was avoided. But there was still the risk of heat soaking into the powder flats and igniting the powder, so the magazines were flooded. It took about 90 minutes to extinguish the fire, and several members of the crew were decorated for their actions during this battle.

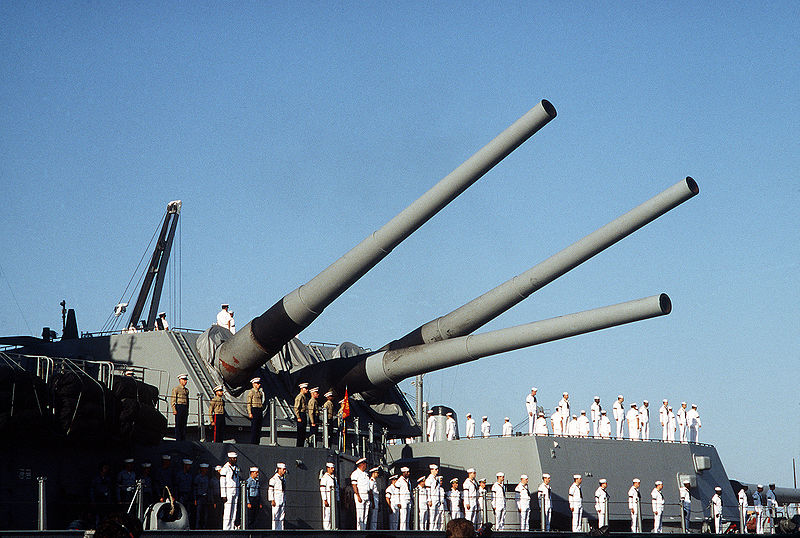

Iowa returns to Norfolk with Turret II still locked in position and the deck blackened

Before Iowa had even made it back to port, questions began about the cause of the explosion, and an investigation was ordered. It was to be headed by Rear Admiral Richard Milligan, assisted by Captain Joseph Miceli, who had been responsible for the reactivation of the 16” guns a few years earlier.

President George H. W. Bush speaking at the memorial ceremony for the crewmen

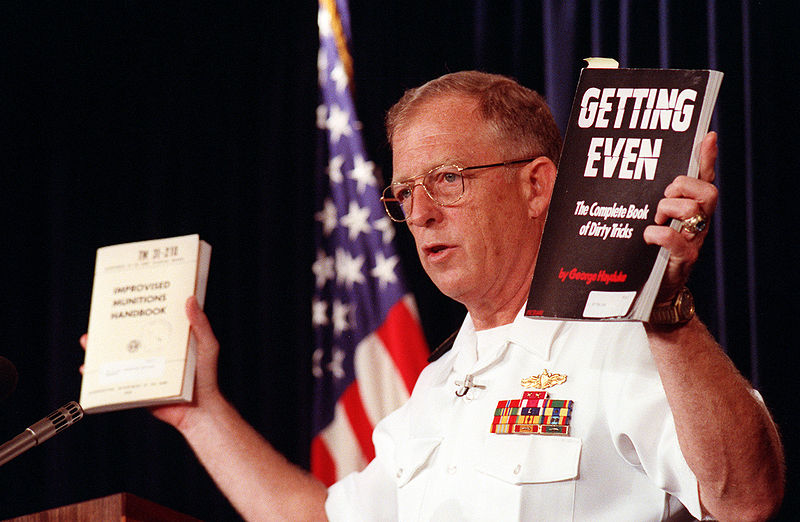

They quickly focused in on one of the sailors killed in the explosion, Gunners Mate Guns 2nd Class Clayton Hartwig. They alleged that Hartwig had been in a relationship with another sailor, Kendall Truitt, and when the relationship ended, had sabotaged the gun in a bizarre murder-suicide. This was supported by a life insurance policy Hartwig had taken out, with Truitt as the beneficiary. The investigators claimed to have detected the chemical signature of an igniter trapped under the driving band of the shell, and that interviews and psychological analysis supported the case against Hartwig.

Admiral Milligan shows books reportedly found in Hartwig's locker at a press conference

These claims produced outrage among the families of the crew, and the Senate Armed Services Committee demanded an independent investigation, run by the GAO and Sandia National Laboratory. This investigation came to quite different conclusions. The ‘chemical signature’ of the igniter was found on the shells that had been in the left and right guns, and the extent of the Navy’s misconduct in the first investigation was discovered. One sailor who had admitted to receiving advances from Hartwig had been interrogated for 8 hours and threatened with being charged as an accessory, stood a 9-hour watch, then been picked up and interrogated for another 6 hours before confessing. When he was asked to confirm his statement, he recanted, but the investigation ignored his retraction. This was only the most blatant of the numerous errors made by the Naval Investigation Service during the criminal portions of the investigation.

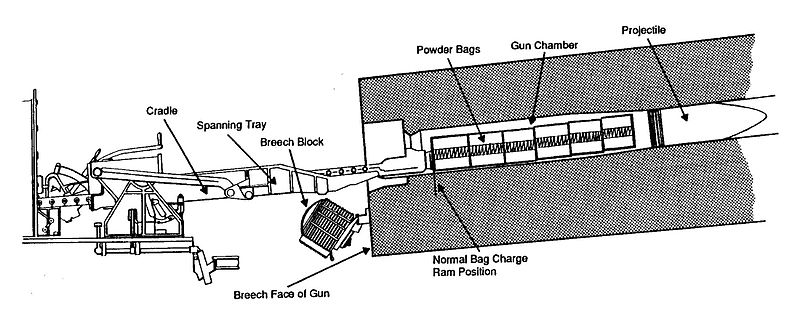

A diagram of the 16" gun loading process

The biggest problem with Sandia’s doubts was the lack of a plausible alternative ignition source. This arrived the day before a critical Senate hearing, when a drop test simulating an overram set off a stack of powder bags. The rammer had two modes, one at high speed for the shells and another at low speed for the powder. If it was operated in the high-speed mode, it might ram the powder bags against the base of the shell hard enough to fracture the propellant grains. The grains in the second bag could burn through and ignite the black-powder igniter patch at the back of the first bag, setting off the entire load of powder. A hasty cleanup had destroyed enough evidence that it was impossible to conclusively prove this theory, but it is in my opinion the most plausible one by far.2

The Navy launched a second investigation, but for some reason left Miceli in charge. He continued to support the initial sabotage theory, but was on increasingly shaky ground. In his book on the accident, Richard Schwoebel, the leader of the Sandia Investigation, portrays Miceli as honestly misguided, apparently unable to believe it was an ordnance failure instead of a human one. Eventually, the Navy punted and the official cause of the accident remains undetermined to this day.

The book A Glimpse Into Hell, by journalist Charles Thompson, claims that there were serious material and personnel problems aboard the Iowa. Crewmembers who were onboard at the time of the explosion do not think it is an accurate portrayal, and I personally find it hard to believe that a ship that had won the Battenberg Cup a mere four years earlier could have fallen so fast. There were some technical issues, including an unauthorized gunnery experiment being conducted at the time of the accident,4 but both investigations ruled it out as a contributing factor.

Iowa's crew fights the fire after the explosion

Turret II was never fully repaired, although most of the damaged equipment was reconditioned and stowed inside Turret II before the ship decommissioned. Turret II remains sealed, and will not be opened to the public. Every April 19th, a memorial service is held aboard Iowa, and there’s a museum of naval gunnery accidents belowdecks.5 One former crewman characterized the accident as a really bad day, which we shouldn't let overshadow the memory of all the good days.

Iowa off the coast of Lebanon in company with the cruiser Belknap, the carrier Coral Sea, and the amphibious ship Nassau

Despite the disaster, Iowa and her crew weren't allowed to rest. On June 7th, a European deployment began, taking Iowa to Kiel, Portsmouth, Rota, Casablanca, Gibraltar and Marseilles. In August, a crisis in Lebanon brought the ship into the Eastern Mediterranean, and she was briefly the Sixth Fleet Flagship. I don't have many details, but it could have become very exciting in a hurry. This crisis brought Iowa to Turkey, Israel, Egypt, Corsica and Italy before she returned home in late November. On the Atlantic crossing, she fired the last of 2,873 16" rounds since the reactivation.

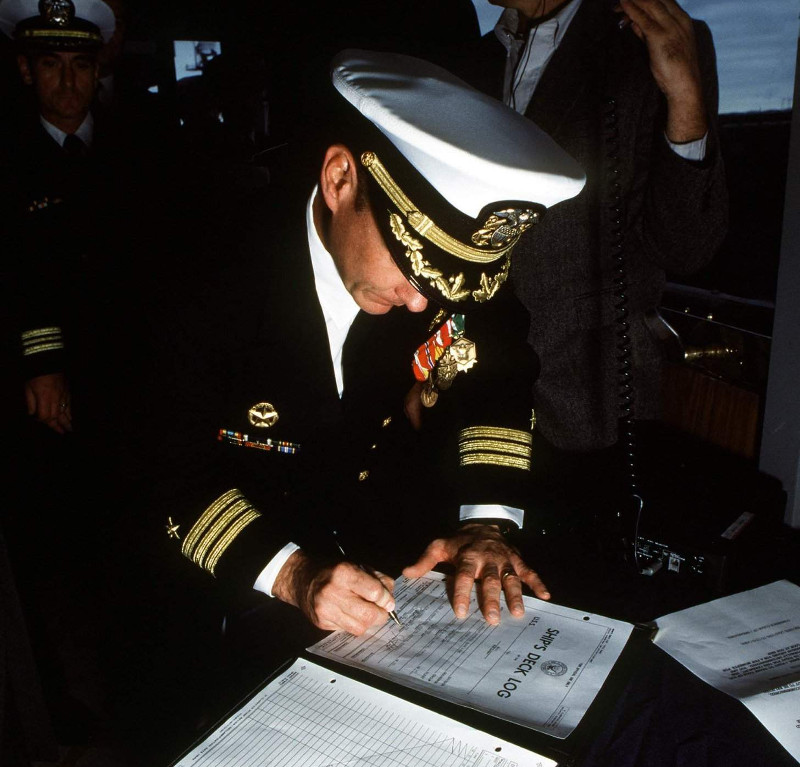

Commander John P. Moorse, Iowa's last Captain, signs the last entry in the ship's log during the decommission ceremony

At this point, the writing was on the wall for the battleships. Their role as cruise missile platforms had been rendered obsolete by the Vertical Launch Systems entering the fleet, and the demise of the Soviet Union had removed much of the need for extra capital ships. They were simply too expensive to keep around, particularly as they had been designed in an world where manpower was cheap, and that was no longer the case. Iowa only went to sea again briefly after returning home from the Med, and was formally decommissioned on October 26th, 1990. New Jersey followed her in February, while Missouri and Wisconsin saw action one last time, supporting the liberation of Kuwait. Missouri was kept in commission with a skeleton crew until early 1992, to allow her to be present at the 50th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attacks. Iowa's service with the fleet was over, but her story had one more chapter to run.

A flag hoist on Iowa's deck just after she decommissioned

I'll close this with a list of the casualties of the explosion:

- Tung Thanh Adams - Fire Controlman 3rd class (FC3) Alexandria, VA

- Robert Wallace Backherms - Gunner's Mate 3rd class (GM3)(FC3) Ravenna, OH

- Dwayne Collier Battle - Electrician's Mate, Fireman Apprentice (EMFA) Rocky Mount, NC

- Walter Scot Blakey - Gunner's Mate 3rd class (GM3) Eaton Rapids, MI

- Pete Edward Bopp - Gunner's Mate 3rd class (GM3) Levittown, NY

- Ramon Jarel Bradshaw - Seaman Recruit (SR) Tampa, FL

- Philip Edward Buch - Lieutenant, Junior Grade (LTjg) Las Cruces, NM

- Eric Ellis Casey - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Mt. Airy, NC

- John Peter Cramer - Gunners Mate 2nd class (GM2) Uniontown, PA

- Milton Francis Devaul Jr. - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Solvay, NY

- Leslie Allen Everhart Jr. - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Cary, NC

- Gary John Fisk - Boatswains Mate 2nd class (BM2) Oneida, NY

- Tyrone Dwayne Foley - Seaman (SN) Bullard, TX

- Robert James Gedeon III - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Lakewood, OH

- Brian Wayne Gendron - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Madera, CA

- John Leonard Goins - Seaman Recruit (SR) Columbus, OH

- David L. Hanson - Electricians Mate 3rd class (EM3) Perkins, SD

- Ernest Edward Hanyecz - Gunners Mate 1st class (GM1) Bordentown, NJ

- Clayton Michael Hartwig - Gunners Mate 2nd class (GM2) Cleveland, OH

- Michael William Helton - Legalman 1st class (LN1) Louisville, KY

- Scott Alan Holt - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Fort Meyers, FL

- Reginald L. Johnson Jr. - Seaman Recruit (SR) Warrensville Heights, OH

- Nathaniel Clifford Jones Jr. - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Buffalo, NY

- Brian Robert Jones - Seaman (SN) Kennesaw, GA

- Michael Shannon Justice - Seaman (SN) Matewan, WV

- Edward J. Kimble - Seaman (SN) Ft. Stockton, TX

- Richard E. Lawrence - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Springfield, OH

- Richard John Lewis - Fire Controlman, Seaman Apprentice (FCSA) Northville, MI

- Jose Luis Martinez Jr. - Seaman Apprentice (SA) Hidalgo, TX

- Todd Christopher McMullen - Boatswains Mate 3rd class (BM3) Manheim, PA

- Todd Edward Miller - Seaman Recruit (SR) Ligonier, PA

- Robert Kenneth Morrison - Legalman 1st class (LN1) Jacksonville, FL

- Otis Levance Moses - Seaman (SN) Bridgeport, CN

- Darin Andrew Ogden - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Shelbyville, IN

- Ricky Ronald Peterson - Seaman (SN) Houston, MN

- Mathew Ray Price - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Burnside, PA

- Harold Earl Romine Jr. - Seaman Recruit (SR) Brandenton, FL

- Geoffrey Scott Schelin - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GMG3) Costa Mesa, CA

- Heath Eugene Stillwagon - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Connellsville, PA

- Todd Thomas Tatham - Seaman Recruit (SR) Wolcott, NY

- Jack Ernest Thompson - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Greeneville, TN

- Stephen J. Welden - Gunners Mate 2nd class (GM2) Yukon, OK

- James Darrell White - Gunners Mate 3rd class (GM3) Norwalk, CA

- Rodney Maurice White - Seaman Recruit (SR) Louisville, KY

- Michael Robert Williams - Boatswains Mate 2nd class (BM2) South Shore, KY

- John Rodney Young - Seaman (SN) Rockhill, SC

- Reginald Owen Ziegler - Senior Chief Gunners Mate (GMCS) Port Gibson, NY

1 The powder flat is the powder storage area around the base of the turret, several decks down. More details on Iowa's turrets can be found here. ⇑

2 Some of Iowa’s staff have told me that they think there are serious problems with this theory. I’ve not been given any details, but any new information will result in a revision of this post. The most detailed rebuttal to this narrative I've heard is that Sandia's test crushed the powder more than it possibly could have during an actual overram, but I haven't seen numbers on this, and there's never been an alternative seriously proposed. ⇑

3 Bloomers are the black bags that serve as weather seals where the guns pass through the turret faceplate ⇑

4 The gun was loaded with five (instead of the normal six) bags of D846 propellant, which was intended for use with the 1900 lb shell. The experiments may have contributed to crew confusion, but they weren't directly causal. ⇑

5 I attended the ceremony in 2019, and it was very touching. ⇑

Comments

A question about the photographs of the disaster, and the battle photography in earlier posts: do Navy ships have permanently assigned photographers that just, you know, stand around during battles taking snaps for posterity? Even back in WW2? In the modern era I could imagine embedded journalists, but I would have thought the old school navy would see that as pointless...did they have a strong respect for documenting history, or want training data, or PR? Whence comes old school battle photography?

A good question, and one I don't know the answer to offhand. Modern ships do usually have media specialists whose job it is to stand around taking pictures, and I'd guess that's where the pictures I used here came from. A gun shoot is a fairly major event, and they'd presumably send the photographer over to take pictures. What I don't know is what their duties are in combat. They might be assigned to record things for posterity (which means 'the action report'), or they might be on damage control duty (or something of that nature). And I don't know about WWII, either. The relative paucity of combat photos could be that most of them are in archives and not online, but it more likely reflects that most just didn't get taken. For instance, there are about half a dozen of the main action at Suriago on history.navy.mil, all taken by Pennsylvania, and wikimedia doesn't have any more.

Hey bean, what is the bright green coating (fluid?) on Iowa's deck in the seventh picture? Fire retardant?

I think it's probably something of that nature. Either that, or hydraulic fluid leaking due to the damage in Turret II.

What are the biggest drivers of the cost of maintaining a battleship? Is there anything ship designers can do about reducing maintenance costs, and has anybody ever done much in that direction (beyond the common practice of mothballing ships for long periods of time when they aren't urgently needed)? I guess I'm wondering if this is something where they've done as much as they can, or alternately whether it might be something that's been neglected due to the unsexiness of practical and logistical concerns (or some combination, or whatever; at present I know absolutely nothing about this topic, and am looking to get to a point of knowing more than nothing).

It was mostly a matter of manpower. Iowa was originally designed with a crew of ~1900, but the 80s refits brought that down to 1500. Which was still like 5 destroyers worth. Manpower has gotten a lot more expensive since WWII, but the ships were designed when it was cheap. For instance, modern ships are set up so that they can be resupplied using a forklift and pallets. The Iowas didn't have those passages, and stores had to be struck down with long chains of men. Keeping cost down was actually a fairly serious consideration during the modernizations, so they couldn't tear out everything and bring them up to full 80s habitability/manning standards.

I see a couple of sailors with the rank of "Legalman 1st class" among the dead. Paralegals, presumably? Strange that they had anything to do with this.

A 16" turret requires a lot of manpower, and much of it doesn't need to be particularly skilled in the art of running heavy guns. (The guys who pass powder around, for instance.) So they would bring in sailors from other departments to fill those slots. After all, you don't need the legal department in the heat of battle.

Going into the turret was voluntary, and that anyone who volunteered was told that if something went wrong, the magazines could be flooded immediately, without giving anyone inside the chance to escape.

Some discussion on this recently came up on another board I am thanks to BHR's fire. A guy there had been a midshipman doing his cruise right after the accident; smoke pit gossip (believed by at least some of the JOs) was absolutely that FCCM and his experiments were involved somehow, but the CPO mess banded together to make sure there was nothing to really prove.

It's odd that the navy stressed that what they punished Skelley for wasn't related to the accident (according to an old WaPo article). But then they wouldn't want to undermine the official story.

(Btw, why do they abbreviate it as CM rather than MC?

As for why the higher CPO grades are "CS" and "CM" instead, it's probably to make various things easier - stenciling, sorting, all kinds of things that could get squirrely if FCC Jones became FCSC Jones instead of FCCS Jones. And then, since you already have "CS", might as well go with "CM" instead of pivoting to "MC" at that point.

That said, when you see "Senior Chief" or "Master Chief" abbreviated without the rating added, it'll be rendered as "SCPO" or "MCPO".

@Blackshoe

I'm a bit skeptical of that. I have a healthy regard for the capabilities of the Goat Locker, but I'm not sure how they could have hushed something like that up. Particularly on the physical evidence side. Also hard to see why they'd shield Skelley if he was responsible for 47 deaths, including one of their own.

(Also, I've heard lots of crazy stuff from people over the years, so tend to take that with a lot of salt.)

@bean: I don't 100% believe it, but I also don't 100% discount it, either. I can figure a lot of ways that the Chief's Mess could make a cover-up work if they really wanted to. Given how the USN's investigation did go, it would explain why that's the route they ended up going down.

The "green water" was the fluorescent dye marker leaking from the life jackets being "soaked in sea water" from all the fire hoses/water being spraying towards Turret II.

Ah. That makes sense, and now that you mention it, it does look like the dye markers I've seen elsewhere. Thanks.