While everyone has heard of Bismarck and Yamato, almost no one has heard of the battleships of Italy's navy, the Regia Marina. What makes this odd is that the Italian battlefleet might well have had a greater impact on the course of the war than the battleships of the other two Axis powers.

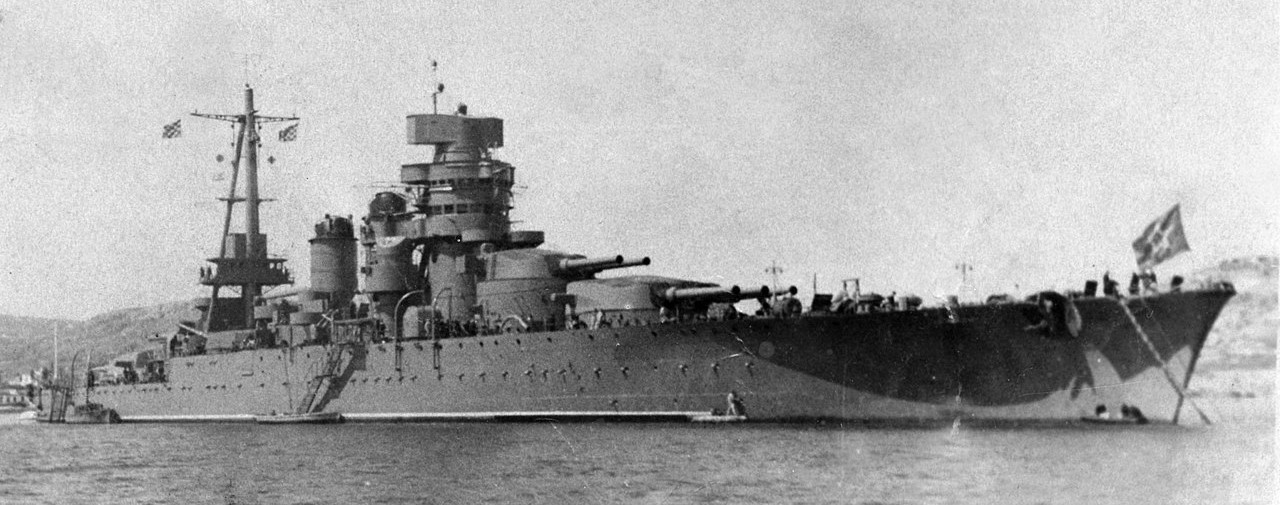

Conte di Cavour

Italy began the war with a mere six battleships, four of them leftovers from WWI. These ships, split between the Conte di Cavour and Andrea Doria classes, had been the beneficiaries of the most extensive reconstruction received by any battleship in the interwar era. Their speed had risen from 21 to 26 kts at the sacrifice of the triple turret previously carried amidships, while the remaining 10 guns were bored out from 12" to 12.6". The deck armor was increased and a Puligese torpedo defense system was installed. All told, only about 40% of the original structure remained unaltered after the reconstruction.

Vittorio Veneto of the Littorio class

The last two battleships were the first of the true treaty battleships, members of the Littorio class. They had been laid down in 1934, and were completed in 1940, just as Italy entered the war. Two more had been started in 1938, but only one of them, Roma, was completed before the Italian Armistice in 1943. The last, Impero, made it into the water but was seized by the Germans before she was completed, and ultimately sunk.

Caio Duilio of the Andrea Doria class

The very existence of these ships had profound consequences when Italy entered in the war in June 1940. The Mediterranean route to India and the Far East, a key lifeline of the British Empire, was cut, and the various British possessions around the Middle Sea were placed in peril. The situation was made worse by the collapse of France, which had previously provided the bulk of Allied naval forces in the Mediterranean. Now, the British found it necessary to commit everything they could spare from Home Fleet to the Med, in an attempt to win the battle for North Africa by cutting Axis supply lines.

Giulio Cesare firing at the British off Calabria

The first major encounter between the two sides came off Calabria, as both sides attempted to shepherd convoys across the sea. After an initial cruiser clash, Warspite traded fire with Giulio Cesare and Conte di Cavour, the British ship scoring one of the longest-range gunfire hits in history before both sides withdrew. Things were fairly quiet for the next few months, until the British launched an attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto using carrier-based Swordfish torpedo bombers. Of the six battleships present, Conte di Cavour was sunk and never returned to service, while Littorio and Caio Duilio were damaged but back in action by mid-1941. This attack, a spiritual successor to one planned on the High Seas Fleet in late 1918, probably inspired a similar effort by the Japanese a year later.

The damage to Littorio after the Taranto attack

After Taranto, the two operational battleships attempted to harass the British convoys, ending the year with another indecisive clash involving both sides' battleships off Cape Spartivento. The Italians, under orders to avoid action unless the odds were heavily in their favor, broke off after a few salvos.

Vittorio Veneto engages British cruisers at Cape Matapan

In April 1941, the British sent troops to Greece, covered by their Mediterranean Fleet. The Italians, lead by Vittorio Veneto, attempted to interfere, only to discover that the British had three battleships and a carrier available. They immediately turned for home, but Swordfish torpedo bombers from the carrier caught the battleship and managed to lame her. Unlike Bismarck, similarly damaged a month later, Vittorio Veneto managed to escape, while the British caught several cruisers and sank them in a night action.

Littorio

Late 1941 saw the balance of power change decisively against the British. The ships that were to have deterred Japanese adventurism were instead facing the Italians in the Med, and the Japanese used the opportunity to secure most of Southeast Asia. The handful of ships the British could spare were sunk in the opening days of the war, and more had to be dispatched to protect India, leaving the Med even more thinly-held. To make matters worse, two British battleships were disabled by commando attack, leaving the Italian fleet as the most powerful in the theater. It quickly gained control of the central Mediterranean, isolating Malta and ensuring a steady flow of supplies to the Axis armies in the desert. In some cases, British convoys turned back on the report of Italian battleships at sea, although on the few occasions where the Italian dreadnoughts did catch a convoy, the much lighter British escort drove them off.

Giulio Cesare, sister to Conte di Cavour

The balance finally shifted back to the Allies in late 1942. The invasion of Morocco and Algeria gave the Allies a second front in North Africa, and military successes there gave more airbases to cover the central Mediterranean. Fuel shortages immobilized the Italian battleships, and in September 1943, Italy capitulated. The Allies, fearful of the remaining ships falling into German hands, insisted they be handed over.

Roma exploding after the Fritz-X attack

The Italians complied, with six battleships sailing for Malta. The older battleships, sailing from southern Italian ports, arrived unmolested, but the three Littorios, based at La Spezia in northwestern Italy, were caught by German aircraft carrying a new weapon, the Fritz-X antiship guided bomb. Two of the bombs hit the just-completed Roma, setting off the forward magazine and sinking the ship in minutes, while Italia1 was damaged by a third. This action was one of the most important of the war, showing as it did that guided weapons could let even a small number of aircraft sink a battleship, a feat that had previously required dozens of planes.

Andrea Doria surrendering at Malta

Despite this setback, all of the remaining Italian vessels were soon interned, and on September 11th, 1943, Admiral Andrew Cunningham sent a message to London: "Be pleased to inform Their Lordships that the Italian Battlefleet now lies at anchor under the guns of the fortress of Malta."

Novorossiysk, formerly Giulio Cesare, in Soviet service

Postwar, Vittorio Venetio, Italia and Giulio Cesare were allocated among the Allies as war prizes. The two modern ships went to the British and Americans, who scrapped them, while Giulio Cesare became a training ship for the Soviet Black Sea Fleet under the name Novorossiysk until she was destroyed by an internal explosion in 1955. The two Andrea Dorias remained in Italian service, alternating roles as fleet flagship until 1953, when both were stricken and later scrapped.

Vittorio Veneto and Littorio

Despite their odd history and lack of any high-profile actions, the Italian battlefleet did what it was intended to, placing Italy in contention for control of the Mediterranean. This was more than either the German or Japanese fleets managed, and it also had a huge influence on the war in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, as the British were unable to deploy to meet the growing Japanese threat. Ultimately it was undermined by lack of fighting spirit and oil, but the effort made was greater than that of the other Axis powers.

Comments

The wiki link for the Raid on Alexandria is broken; it requires 1941 to be in parentheses.

Neat to read about some of the action in the Mediterranean; it's not something I've really been exposed to through cultural osmosis.

Fixed. That's one of the oddities of my links, and I usually remember to fix them before the post goes live.

The war in the Med is definitely an interesting one, and the only thing from WWII at sea with more importance and less exposure is the later half of the Solomons campaign.

It's hard to have high profile actions when there's never enough fuel to put to sea. It must have been extremely frustrating being an italian admiral in ww2.

Fuel was a reason there weren't more actions, but I listed several here that could have been high profile if the Italian admirals had been concerned with actually closing with and destroying the British. I suspect the most frustrated man in the Med was the German liaison officer.

@bean

Just looking over the wiki summaries, I can see where the Italians were reluctant to press the issue with the British destroyer fleets. They had been shown earlier their complete inability to fight the British at night due to lack of radar. I assume this extended to not wanting to have any of their battleships wounded such that they couldn't withdraw, which is the type of damage torpedoes seem to excel at. Sinking a few destroyers only to have a battleship lamed and then picked apart in the darkness was certainly a trade they weren't interested in making.

The British in turn seemed to be aware of this and just made it their goal to stall until sunset. It also seems to me like the Italian destroyers were outclassed, which would have made forcing the fight all the more difficult for the Italians if the British were intent on running out the clock.

But everyone was reluctant to press action against destroyer fleets. Half of British tactics during WWI were making sure that their battleships didn't get torpedoed. The Italians were unique in never pressing an action no matter what their advantage.

Somehow I never thought about the fact that if Italy hadn't at least somewhat held its own navally, there couldn't have been a North African Theater. Nor had I known that the British were denied transit of the Mediterranean. Definitely an overlooked part of the war!

I’d say the Littorio’s were deserving of at least some respect. The TDS was a failure, but the decapping system over the main belt was a neat design, and the main armament was quite potent, even if the QC on the ammunition was lacking.

I'm not trying to beat up on the Littorios, which I actually quite like. It's a survey post focusing on the operational side of things, and I chose not to say much about them one way or the other.