John Arbuthnot "Jackie" Fisher was perhaps the most important naval officer of the 20th century, despite never commanding a fleet in battle. His career began on the deck of a wooden sailing ship and ended with a fleet of dreadnoughts, destroyers, submarines and even the first steps towards aircraft carriers. Even more astonishingly, he was the man most responsible for many of these developments, some of which continue to shape naval warfare today.1

Jackie Fisher

A brilliant, energetic, innovative, and ambitious man, he was also stubborn and prone to obsession. At his best, he saw the shape of things to come better than any of his contemporaries, and even better than many today. At his worst, he assumed that the future had already arrived, and tried to build ships that were simply not possible yet. He was a constant proponent of reform, ranging from improving conditions for enlisted seamen to the development of Dreadnought, but was uncompromising in his dealings with those he saw as his enemies.

Fisher was born on 25 January 1841 in Ceylon2 to British parents, but due to his family's precarious financial situation, he was sent to England to live with his grandparents when he was six. In 1854, at age 13, he entered the Royal Navy as a naval cadet, aboard Nelson's flagship, HMS Victory.3 His first ship, HMS Calcutta, was built in 1831, and propelled entirely by sail. On Fisher's first day aboard, eight men were flogged. He was among the last officers of the Royal Navy trained entirely at sea in the traditional manner, instead of attending school ashore first. Calcutta was deployed to the Baltic during the Crimean War, and Fisher probably saw the bombardment of Bomarsund from there.

Fisher as a midshipman

Two years later, Fisher was promoted to midshipman and sent to join the sloop Highflyer, on the China Station. The Second Opium War had just broken out, and Fisher served with distinction in several actions, most notably the abortive attempt to seize the Tauk forts in 1859. In 1860, he was promoted to acting Lieutenant, returning to England a year later. Shortly after his arrival, he took his examinations for his permanent Lieutenancy, and received the highest grade ever recorded for navigation, as well as top marks in gunnery and seamanship. He was then sent to HMS Excellent,4 the Royal Navy's gunnery school and research facility. In 1863, he joined HMS Warrior as her Gunnery Lieutenant. After that tour, he returned to Excellent, where he became one of the first British advocates of the Whitehead torpedo.

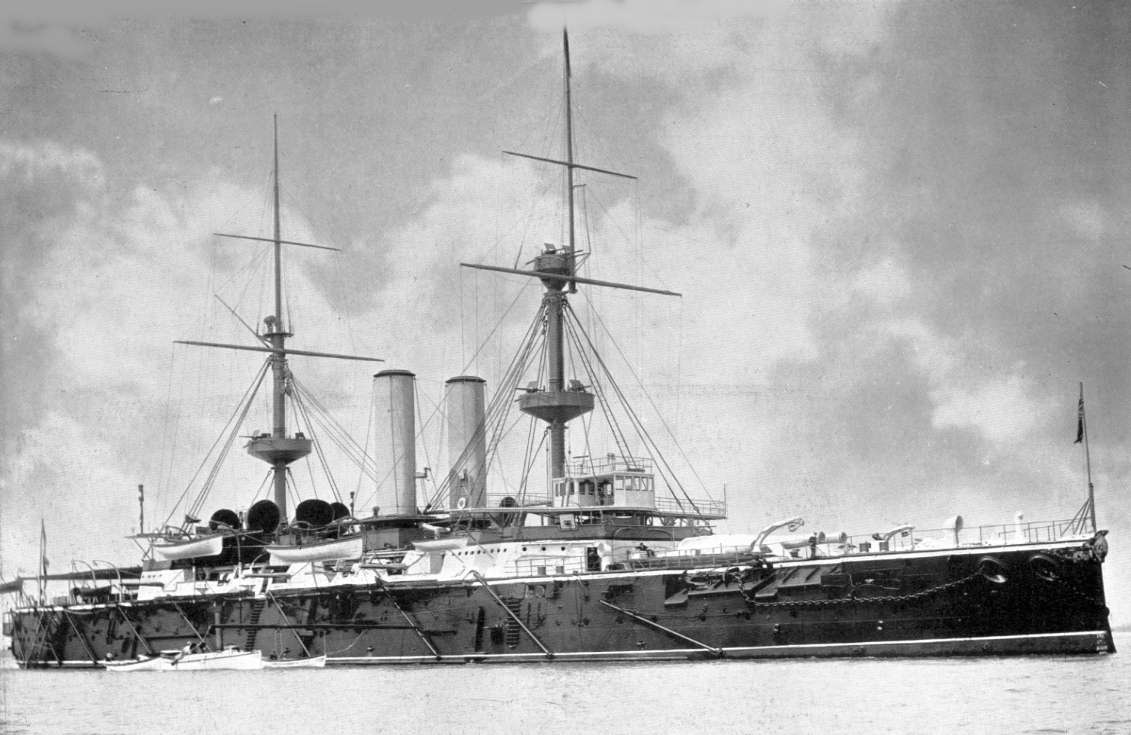

HMS Ocean

Fisher was promoted to Commander at the early age of 28, and posted as second-in-command of HMS Ocean, flagship of the China Station. He was sad at his separation from his wife, who he had married in 1866, and the interruption of his work on the torpedo. While there, he installed an electrical firing system, the first on any RN warship. After two and a half years there, Ocean returned to England and Fisher was assigned again to Excellent as head of the torpedo section, which was later split off as HMS Vernon.

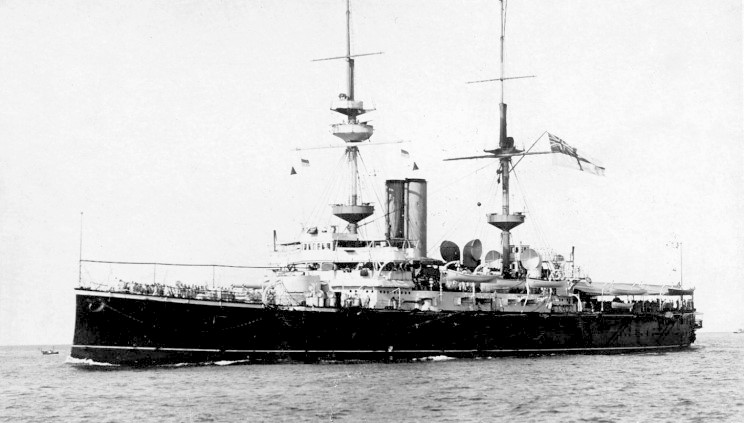

HMS Inflexible

Fisher was promoted to Captain in 1874, at age 33. Two years later, he returned to sea, as Flag Captain5 to Admiral Astley Cooper Key. Aboard his first command, HMS Bellerophon, he told the inexperienced crew "I intend to give you hell for three months, and if you have not come up to my standard in that time you'll have hell for another three months." He indeed gave them hell, but they reached his standards within the allotted three months. He passed through several other commands before being given HMS Inflexible in 1881. Inflexible was the most prestigious ship in the fleet, with the largest guns and thickest armor. While in command, he met Queen Victoria and became friends with the future Edward VII, as well as commanding during the bombardment of Alexandria. After the bombardment, he commanded a landing party, which brought him to public attention for the first time. He also contracted malaria, which caused the Admiral to order him home, stating "the Admiralty could build another Inflexible, but not another Fisher."

Fisher in 1883

Fisher recovered, and returned to Excellent once again, this time as commanding officer. While there, he assembled a group of young officers who shared his interest in improving the fleet, known as the "fishpond". The most prominent members were John Jellicoe, who later commanded at Jutland and Percy Scott, who was instrumental in the development of fire control. In 1886, he became Director of Naval Ordnance, responsible for naval weapons. While there, he fought for the development of the quick-firing (QF) gun, which in turn led to the rise of the pre-dreadnought.

HMS Royal Sovereign

In 1890, Fisher was promoted to Rear Admiral, and given command of Portsmouth Dockyard, where he managed to greatly increase productivity, and build the Royal Sovereign in record time. His next appointment was as Third Sea Lord, the officer responsible for procurement and upkeep of all ships and equipment. The torpedo boat was an increasing threat during this era, and Fisher conceived a ship to fight them, using the latest marine engineering technologies to reach the necessary speed and small QF guns. He christened the resulting ship the torpedo boat destroyer, subsequently shortened to destroyer.

HMS Havock, the first destroyer

After five years as Third Sea Lord, Fisher was sent to sea again, this time to the North America and West Indies Station. He was a success there, but more was to come. As a reward for his performance there, and for his work as a delegate at the Hague Convention, he was given command of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1899. At the time, this was the most important and prestigious seagoing posting in the Royal Navy, and Fisher made his mark quickly.

HMS Renown, Fisher's flagship in the Mediterranean

Before Fisher's arrival, the Mediterranean Fleet had been a rather calm, traditional command. He immediately began a program of intensive training, just as he had done throughout his career, and set up lectures and prizes for tactics, torpedoes, and gunnery. To deal with the combined threats of the French and Russian fleets, he also instituted new methods of gathering and using intelligence that would ultimately be the ancestor of modern command-and-control techniques.

Fisher while in command of the Mediterranean Fleet

In 1902, Fisher handed over the Mediterranean Fleet, and returned home as Second Sea Lord, in charge of naval personnel. He integrated the previously-separate engineering branch with the rest of the navy, and extended naval cadet training before he went to command the naval base at Portsmouth.

HMS Dreadnought

All of this made Fisher the perfect choice for First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy. In 1904, Britain faced a serious fiscal crisis. The burden of the Boer War and the cost of building armored cruisers for trade protection meant that the Exchequer was close to the breaking point. Fisher offered a set of radical changes to bring spending under control and increase military effectiveness. For trade protection, battlecruisers, directed from the Admiralty, would replace the armored cruisers, while the all-big-gun battleship would give more firepower than its predecessor for a given cost. Amid great public controversy, Fisher also discarded most of the long-obsolete reserve fleet. All of these measures worked, at least in the short term, although the later naval arms race with German ran British budgets up again.

Fisher as First Sea Lord

Fisher also introduced other reforms. He was an early proponent of the submarine, believing that in the long term, it would render the surface ship obsolete. He pushed for the introduction of oil fuel, although it was limited to destroyers during his tenure. And he continued his lifelong advocacy for tactical effectiveness and preparedness for war.

HMS Holland 1, the RN's first submarine

In 1909, he was made Baron Fisher, and adopted the motto "Fear God and dread nought". In 1911, on his 70th birthday, he retired, but was recalled to the job in 1914, when the occupant of the post, Prince Louis of Battenberg, was forced to resign due to his German background. He was an advocate of operations in the Baltic, which produced some unusual ships. In May of 1915, he resigned in protest over the failed attempt to secure the Dardanelles, which he had opposed as a distraction from the Baltic.

HMS Incomparable behind HMS Dreadnought

So what do we make of Jackie Fisher? On one hand, he was a genius, participating in every major development in naval warfare before 1915. On the other hand, he became increasingly eccentric towards the end of his life, insisting on the primacy of speed over armor, a trend most famously displayed in his design for "HMS Incomparable". I suspect that his faculties had begun to decay by the end of his service career, but that should not diminish his status as the architect of 20th-century naval warfare.

1 Even teenage girls owe him a debt, actually. He's also the inventor of the abbreviation OMG. ⇑

2 Now Sri Lanka. ⇑

3 This was entirely ceremonial. Victory was basically a hulk at this point, and his first assignment to a ship came less than two weeks later. ⇑

4 All RN shore facilities are technically considered warships, as the Naval Discipline Act only applies to officers and men carried on the books of a ship. ⇑

5 The captain in command of an Admiral's flagship, usually hand-picked by the Admiral for the job. ⇑

Comments

I was amazed at how much his personal correspondence comes off like the texting history of a bubbly modern teenage girl. Lot's of "OMG" and multiple exclamation points following things written in ALL CAPS!!!. All it's missing is the occasional emoticon (which I think he definitely would have used, had it been a thing).

I totally forgot to mention that he’s probably the inventor of OMG. I haven’t read much of his correspondence, but I definitely know what you mean. The man was just different. Also, why am I now picturing an anime about Fisher as a teenage girl?

Dear God, man, don't give them any ideas!

A friend pointed out that Jackie Fisher isn't an anime name, but it is the sort of name you might expect a teenage girl to have. He suggested a Disney Channel sitcom from the 90s/00s.