Of the major naval powers, Japan had placed the greatest emphasis on its battleships during the years leading up to WWII. The experience of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars had lead them to conclude that any war with the United States would ultimately be resolved through a Decisive Battle between the battle lines of the two powers. All Japanese war planning centered around this battle, and it is remarkable that they were willing to throw it away and attack Pearl Harbor instead. The idea reasserted itself after the outbreak of war, and even in 1945, after numerous previous "Decisive Battles" had ended in disaster, the Japanese believed that another one could turn the tide.

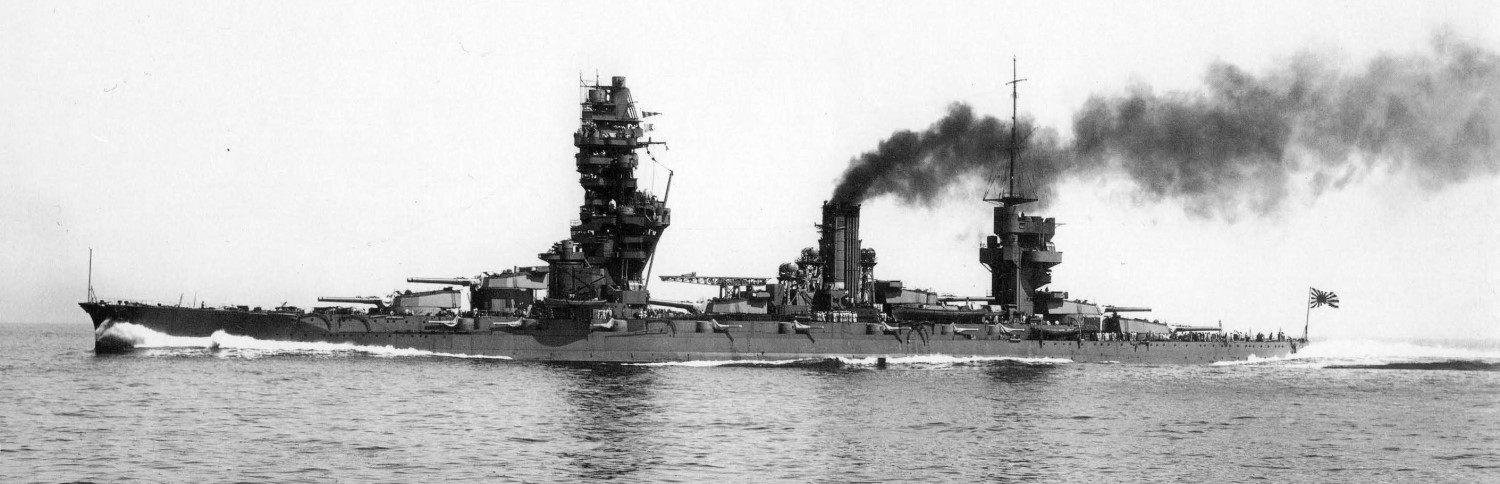

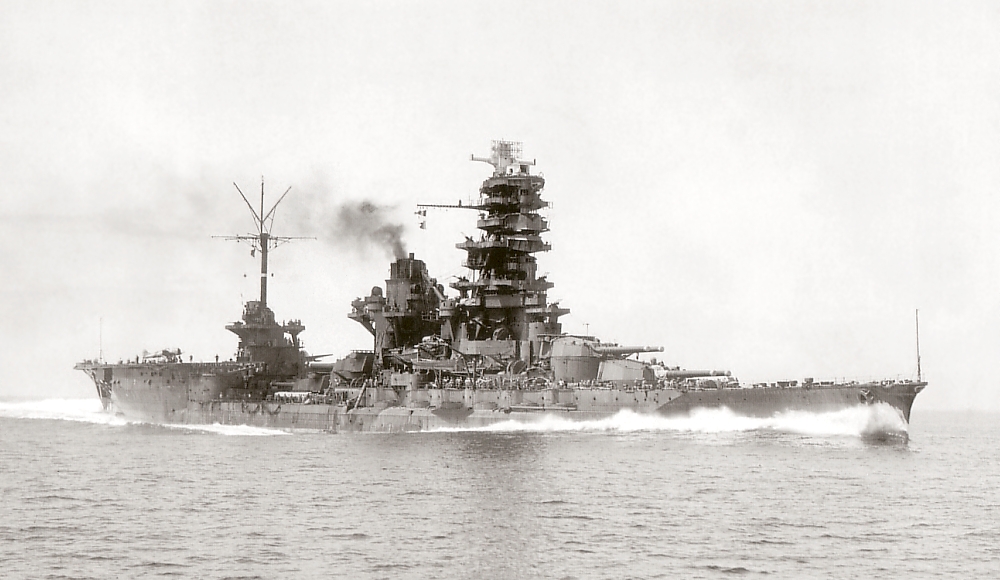

Yamato running sea trials

12 Japanese battleships fought in the war, spread across five classes. The oldest were the four units of the Kongo class. Originally built as battlecruisers before WWI, all four were thoroughly modernized during the 1930s, being reclassified as fast battleships. Capable of 30 kts and armed with 8 14" guns, they proved very useful ships.1

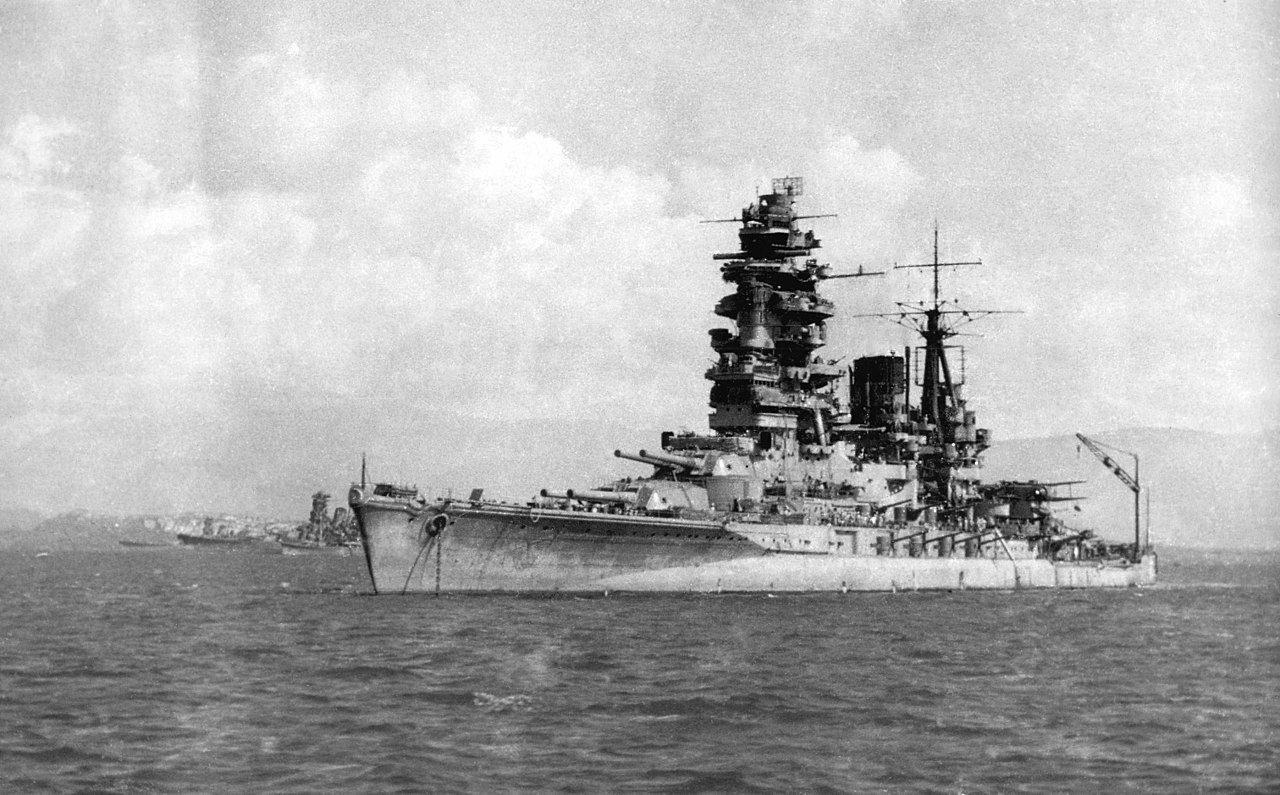

Kongo

The least useful of their battleships were the two Fuso class and two Ise class ships. These very similar ships were armed with 12 14" guns in twin turrets, producing a turret farm surpassed only by HMS Agincourt. Despite extensive upgrades in the 30s, both classes were obsolescent by the outbreak of the war. Significantly more powerful were the two units of the Nagato class. They had 8 16" guns, and their speed of 26.5 kts was significantly higher than any true battleship at the time of their completion, with the exception of Hood.

Fuso. I promise that the hideous pagoda mast is real and not photoshopped.

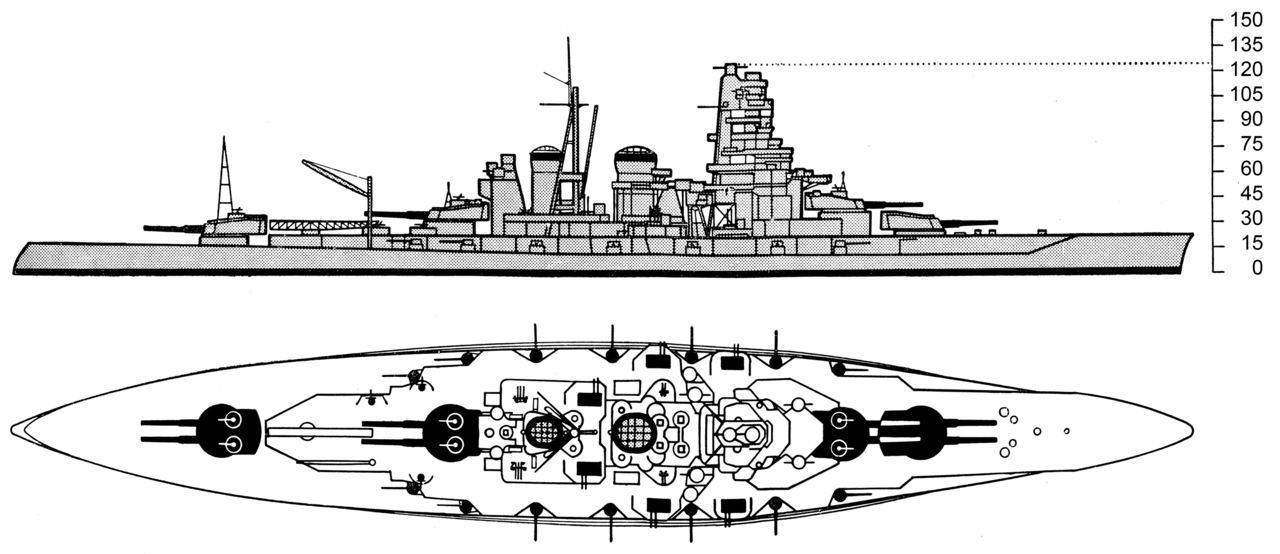

But by far the most famous of the Japanese battleships was Yamato. She and her sister Musashi were newly built, commissioning after the outbreak of the Pacific War.2 They were also the only battleships built to a truly post-treaty design, intended to overcome America's quantitative edge in the Decisive Battle through superior quality. These were the largest and most heavily armed battleships ever, displacing 72,000 tons3 and armed with 9 18.1" guns.

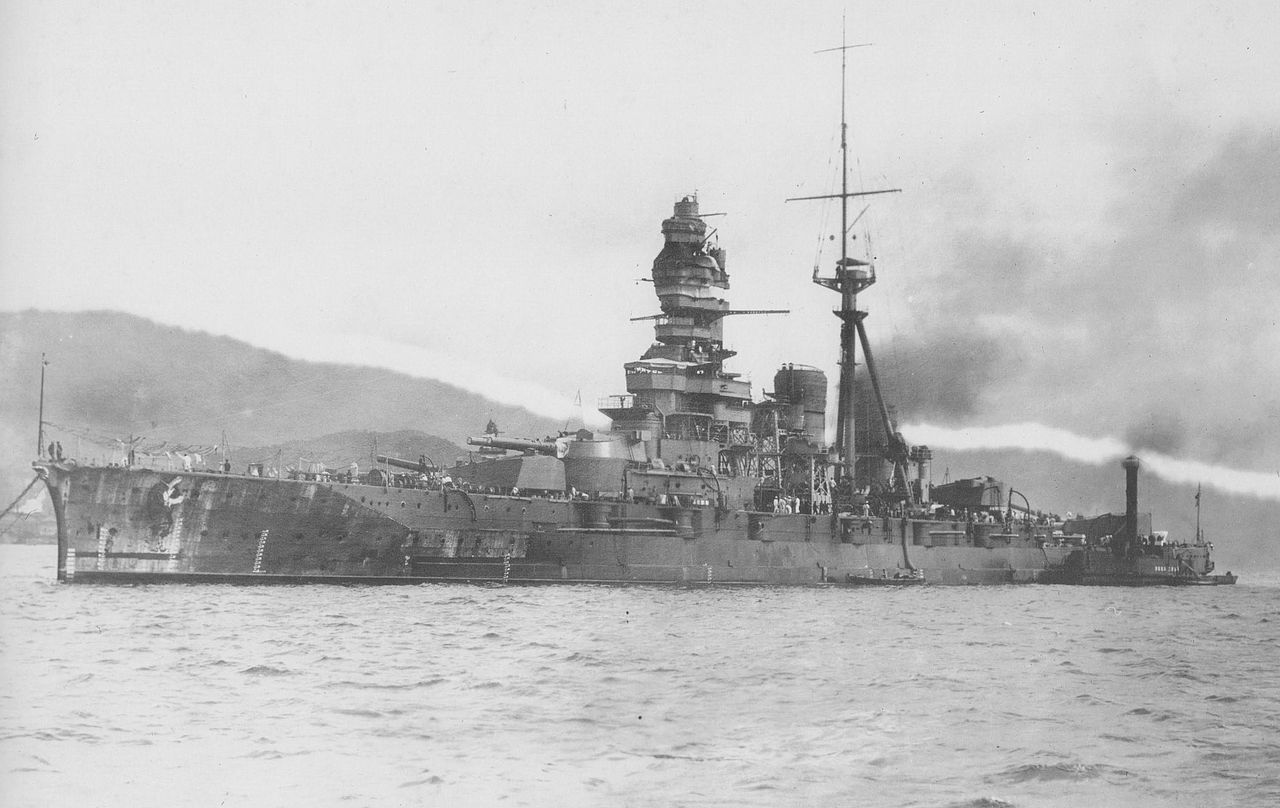

Nagato

Despite, or perhaps because of, their emphasis on battleships, the Japanese proved very reluctant to actually use their vessels.4 All of the classes except the Kongos spent most of the war sitting in port, broken by the occasional deployment as part of a distant covering force for some operation or another. In practice, this meant that they sailed around, hoping the Americans would decide to engage gun-to-gun, then went home without firing a shot.

Kirishima

The Kongos, fast enough to screen the carriers and old enough to be seen as somewhat expendable, had a more exciting life. Two guarded the carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor, while the other two covered the invasion of Malaya. All four fought in the Guadalcanal campaign, Haruna and Kongo bombarding Henderson Field in October. A repeat performance by Hiei and Kirishima was interrupted by the USN. On November 13th, they ran into an American cruiser task force, which they handled very roughly. However, Hiei was badly damaged, and aircraft from Guadalcanal sank her the next day. Kirishima and her consorts returned to finish the job two days later, but found the battleships Washington and South Dakota waiting for them. South Dakota suffered badly after a series of mistakes left her mostly powerless and silhouetted against a burning destroyer, but Washington used her superior radar to sneak up on the Japanese battleship and pump 9 16" shells into her, sending her to the bottom.

Ise after her conversion to a hybrid battleship-carrier

After the losses at Midway, the Japanese high command decided to convert two battleships into hybrid battleship-carriers. Ise and Hyuga5 lost their aft two turrets, and a flight deck with a hangar under it was installed on each ship. An air group of 22 aircraft was specified, half dive-bombers, half reconnaissance floatplanes,6 but the lack of trained pilots meant that neither ship carried this many. Both were part of the decoy force during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, surviving heavy air attack to spend the last year of the war running away from the American carrier groups until they were sunk in Japanese waters in July 1945.

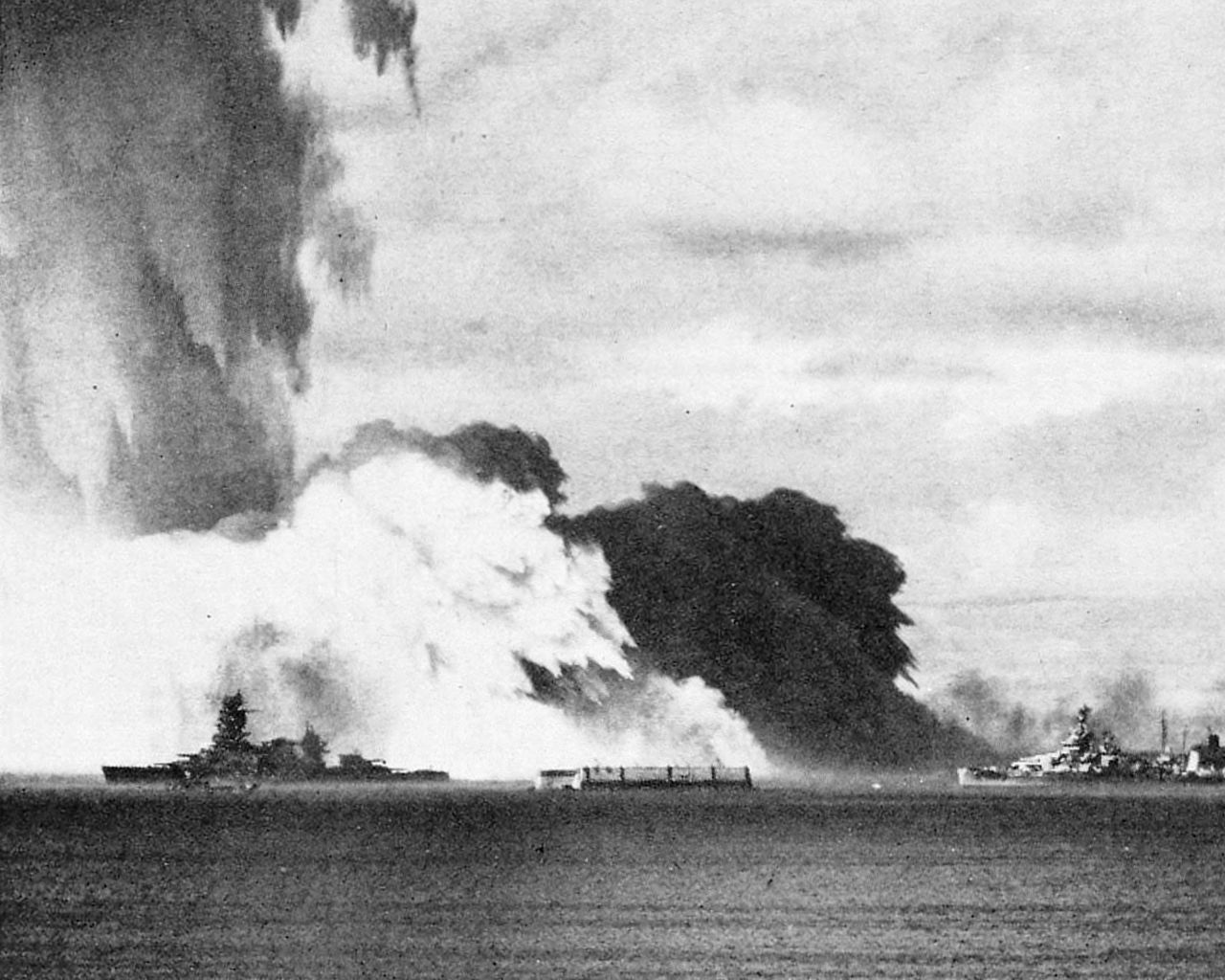

Yamato under air attack during the Battle off Samar

Leyte Gulf was the closest the Japanese came to their Decisive Battle, and all nine remaining battleships participated.7 The basic plan, to draw off the American carriers with the decoy force of Japanese carriers, worked well, but the follow-up, where Japanese battleships would sneak in and destroy the invasion fleet, came apart. The southern force, centered around the two ships of the Fuso class, was destroyed in Surigao Strait by survivors of Pearl Harbor in the last big-gun action in history. The center force, with both Yamatos, Nagato and the surviving Kongos, was detected on the way in and subjected to air strikes, sinking Musashi. The Americans thought they had turned back and focused their efforts on the other prongs of the Japanese attack. The appearance of four battleships on the horizon was a rude surprise to the men of escort carrier group Taffy 3, but they fought back magnificently, driving off the Japanese despite heavy casualties.

Yamato under heavy air attack during her fatal dash for Okinawa

Haruna, much like Ise and Hyuga, was sunk in harbor by American air attack. Kongo was sunk by a submarine, while Yamato was ordered to sortie in April 1945, in a desperate attempt to defeat the American invasion of Okinawa. The idea was to beach Yamato and her escorting destroyers, then use them as heavy artillery until they were destroyed, when their crews would join the defenders on land.8 The lack of air cover doomed the operation from the beginning, and Yamato succumbed to attack by over 400 aircraft. Even if she had survived the air attack, the six fast battleships that had been readied to receive her would have put her on the bottom.

Iowa's crew aboard Nagato at the end of the war

Only Nagato survived the war afloat, although she was an immobile anti-aircraft battery by the time the Japanese surrendered. A crew from the Iowa secured her before the surrender ceremony, and she was ultimately destroyed during the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tests in 1946. Her wreck remains there today.

Nagato is visible in the lower left of this picture, taken moments after the detonation of the Crossroads Baker device

Ultimately, the battleships of Japan were even less useful than their German counterparts. Unlike the Germans or the Italians, the Japanese were unable to leverage their inferior forces to cause their enemies to expend disproportionate efforts countering them, and the battleships spent most of their careers sitting in harbor far from the front lines. Even when they did fight, they did not do so effectively. Only Hiei and Kirishima turned in battle performances that are even vaguely creditable, and neither survived the battle. The most powerful surface force the Japanese ever put together was turned back by a group that together displaced less than Yamato alone did, and was even more massively outclassed in firepower. Ultimately, no part of the Japanese war plan makes much sense in retrospect, but their battleships are a particularly good example of how far behind the Allies the Japanese military was.

1 Interestingly, Hiei, one of the Kongo class, was demilitarized as a training ship under the Washington Treaty. However, unlike the training ships of the other powers, she was turned back into a fully combat-ready battleship after the Japanese withdrawal from the treaty structure. ⇑

2 A third ship, Shinano, was converted into an aircraft carrier while under construction. She was sunk by the submarine Archerfish before she was commissioned, the largest ship ever sunk by a submarine. ⇑

4 In fairness, the desperate Japanese fuel situation played a major part here. Even with access to the oil of the Dutch East Indies, the lack of tankers made it difficult to operate the largest and most-fuel hungry ships. ⇑

5 These ships were selected because during the modernizations, gun elevation had been increased by deepening the gun pits. The shafts had prevented this from being done to the aft two turrets. Hyuga had also suffered a turret explosion in X turret in May 1942. ⇑

6 I'm not sure if they had arresting gear fitted. Landing in the disturbed air aft of the superstructure would be very difficult, but I have no evidence that there was a float version of the dive-bomber. It's possible that the Japanese planned to return them to shore bases or land them on nearby carriers to replace losses. ⇑

7 Besides Hiei and Kirishima, Mutsu, sister to Nagato, had been lost in a freak magazine explosion in June 1943. Weirdly, the Japanese blamed a disgruntled crewman, although modern historians are unsure of the cause. ⇑

8 The whole operation is more than a little reminiscent of the plans of the High Seas Fleet at the end of World War I. ⇑

Comments

Magazine explosion ([i]Mutsu[/i]). Turret explosion ([i]Ise[/i]). One does suspect that there seems to be a something a little lacking in the Japanese approach to safety here. And the "disgruntled crewman" has shades of the US Navy's approach to the [i]Iowa[/i] Turret 2 explosion, no?

The disgruntled crewman is definitely reminiscent of the USN handling of the Iowa investigation. I can't say for certain about their safety practices relative to other powers. The US had at least one turret explosion during the war, and there was Mount Hood and the West Loch disaster, not to mention Port Chicago.

cough "Surigao" cough

Ack. I shall have to reprimand the proofreading staff.

Can you go into more detail in why Pearl Harbor meant Japan throwing away their plans? Thinning the enemy fleet doesn't seem incompatible with building up to a Decisive Battle.

That was based on some old internet conversations I read about their war plans, not a detailed study of Japanese strategy leading up to WWII. The original plan had been to use the Philippines to lure the US fleet out into the Mandates (Marianas and Gilberts, mostly) and sink it in the Decisive Battle there. Pearl Harbor was conceived as an alternative to that, not a supplement. And using all six of your carriers in an insane strike thousands of miles away from your fleet is kind of a departure from their traditional role. For that matter, it was weird to have the carriers as decisive instead of using them in support of the battleships.

Why weren't battleships part of the Pearl Harbor attack plan (either as part of the main plan or a near-term follow-up action - instead of just 2 escorting battleships)? No plan to mop up any ships (like the carriers) that escaped the main attack? With most of the ships and land based aviation at Pearl destroyed, would there have been any plausible resistance to the Japanese battle fleet steaming up to the harbor and shelling everything into unsalvageable scrap (and maybe luring the American fleet carriers back to their doom)? An actual invasion of Hawaii was obviously beyond Japan's capabilities, but a surface warship raid seems plausible.

Obviously the Japanese had plans against the Philippines as well, but it seems obvious, at least in retrospect, that the Decisive Battle would not happen there if Pearl were successfully attacked, because the US fleet would be too stunned and hurt to sail in support of the Philippines. So why not force the issue at Pearl and have the Decisive Battle there?

Was it really just the fuel situation and a lack of long range logistical support capability?

First, because this was the era when "a ship's a fool to fight a fort" was taken seriously. Second, because there were at least 14 battleship-caliber guns guarding Honolulu, and 17 near Pearl Harbor. They might have outgunned the fortifications, but not by enough to be comfortable with getting away with the raid. Also, it's worth pointing out that a battleship raid would have meant a lot more run-in, and they couldn't be sure how well the attack would go. Maybe they suddenly find themselves facing most of the battle line near the islands, and lose. Not to mention that the carriers were seen as mostly expendable, and the battleships weren't. (There was a serious plan to discard some of the carriers during the Pearl Harbor raid due to lack of fuel.)

The other thing about Yamamoto's plan was that it threw away Japanese grand strategy for the war, which was more or less "let's do Tsushima all over again" -- the idea was that the US fleet would sortie out, get attrited on the way, and finally be defeated in a Decisive Battle, thus shattering American will to resist.

But a fleet crippled at Pearl Harbor is not going to sortie out for the Decisive Battle, or any battle, so all Yamamoto really accomplished was making sure the Americans waited until they were all repaired AND the new navy in the shipyards had joined the fight. He postponed the Decisive Battle from 1942 when the Japanese might have had a chance, to 1944 when the Americans had more destroyers than the Japanese had planes.

The Japanese strategy always included a section marked "and then the US will lose the will to continue the fight", apparently on the example of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. Of course, the US is neither state, and at the time, probably wouldn't have the same public morale issues those states did. I think the plan behind the strategy they adopted was to shatter our morale so thoroughly that this would happen early on, instead of shattering it after the Decisive Battle. It's possible that the nature of the Pearl Harbor attack made this task much harder, and that a more conventional approach might have resulted in us accepting some sort of negotiated settlement, particularly if they'd managed to administer a major defeat.

Huh--I always thought Pearl Harbor seemed, ethics aside, pretty wildly successful militarily, and that it probably maximized Japan's slim-to-nil chances of winning that war.

But now that I think about it, one of Japan's most valuable assets was underestimatedness, and they must have burned an awful lot of it in that attack.

Also, thinking about the comparison to Germany... was there a viable way Japan could have taken a similar sea denial approach? Or did their oil needs basically commit them to sea control?

The Pearl Harbor Attack was a serious failure on two levels. First, it was guaranteed to make the US really, really mad, which means that we weren't going to just give up. If the Japanese had basically tricked us into declaring war on them (say, by attacking the Dutch and British), then it's at least possible that they could manage to translate a victory in the Decisive Battle a few months later into a diplomatic settlement. If they declare war on us, then the odds of pulling that off go down, but it's at least within the realm of possibility. With the plan they chose, the war was going to last until we crushed them.

Second, the ships were salvageable, in a way they wouldn't have been in a battle in the middle of the Pacific. They were out of commission for a few months to a couple years, but they came back. So they must have been betting on a quick settlement.

No, Japan's geography committed it to sea control. Islands always need sea control, particularly islands with essentially no natural resources.

At first glance it looks like the difference between the German and the Japanese approach was that the Germans looked at the numbers, concluded they were the (naval) underdogs, and set out to operate as such. The Japanese spent the whole war assuming that they had the more powerful force. OK, at this particular point they didn't have any fuel, and this battle was lost for this particular contingency, and that battle didn't go well because the USA got lucky, and the other incident was just poor judgement... but NEXT TIME it'll be a fair fight and Japan will show their true superiority.

In fairness, there was a lot bigger difference in terms of relative strength. The Japanese thought that their fighting spirit would let them overcome a fairly reasonable numerical disadvantage, maybe 20% or so under the treaty. The Germans realized that they had about two battleships, and the British had at least a dozen, and that maybe a head-to-head fight was a bad plan.

Well, what I was getting at is it's not really a fair comparison in another way: fighting like an underdog wasn't an option for Japan.

bit of derped formatting on this page. the Nagato link paragraph is messed up, and the "or the Italians" link is to the edit-me version of the page.

Really nice presentation of Japan's battleships. Thank you. I enjoyed it a lot.

"Washington used her superior radar to sneak up on the Japanese battleship and pump 9 16″ shells into her, sending her to the bottom"

BB56 did a lot more than pump 9 shells into her. In the night action of November 14-15, 1942 according to Hornfischer's "Neptune's Inferno", she landed at least 20 sixteen inch shells on the surprised Kirishima. Another great read on the battle is "Musicant's Battleship at War" where he describes the Washington firing 75 16" AP rounds and "scoring nine direct hits" which is what I think you were referring to. The serious damage though was likely caused by the near misses that Admiral Lee did not count as hits because they saw shell splashes. The shell splashes were the shells hitting the water just before driving into Kirishima below the water line. BB56 was the right tool at the right place, directed by the right people at a critical point in the war. If you ever visit Arlington, Captain Glenn and Admiral Lee's headstones are quite moving if you know the history. Two standard military stones over the bodies of two very capable, brave men.

Thanks again for the page. Great stuff!

I was probably working from Morison's The Struggle for Guadalcanal, which gives 9 hits as well. I'm skeptical that we can double the number of hits. 9/75 is excellent accuracy, and doesn't leave a huge amount of room to do better. Also worth pointing out that shell splashes are mostly when the burster detonates, not when the shell hits the water, so the vast majority of splashes are ineffective. (You could have shells go off close enough to do underwater damage, although that seems unlikely.)

Bean, thanks for the response. I've never seen anything printed about what constitutes a "good" hit ratio with 16" guns. Also never knew that the sighted splashes were actually burster detonations. Where is that information available? I love this stuff! Give Hornfischers book a read if you haven't already. He is very clear about the shells hitting the water with enough kinetic energy to continue on thru the hull beneath the waterline. Curious if that's just his ideas or if there's research that shows it.

What good shooting looks like is going to depend greatly on range. Above 10% is generally quite good, but 20/75 is pushing into territory that I find somewhat implausible. The number of 20 hits apparently comes from Kirishima's Damage Control officer, who reported 14 above-water and 6 below-water hits. Not sure where 9 hits comes from, probably Washington's action report. It's generally rare to underestimate the number of hits, and I'm not sure how much information the DC officer would have had in the chaos aboard Kirishima.

(Hornfisher's source on this is http://www.navweaps.com/index_lundgren/bbActionGuadalcanal.php)

Re splashes, I now realize that I'm not 100% sure on that, but given the physics involved it makes intuitive sense. On the other hand, that seems like something which might screw up spotting given that shells can travel a reasonable distance underwater. That's not a Hornfisher invention at all. POW had two shells pass under her belt during Denmark Strait, and landed an underwater hit on Bismarck that made about 1000 tons of fuel unusable.

I tried "Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors" about 5 years ago, and didn't like it. His style didn't work for me. And my reading list is quite long. Maybe someday.

Looked into this more, and neither Morison nor Musicant calls out their source for 9 hits. It doesn't seem to be Washington's action report, and the ONI combat narrative (official USN account of the battle, via history.navy.mil) says "about 8" 16" hits.

I did a bit more digging, and I think I was wrong about the splashes. Checking a few photos (thank you, past me, for getting decent photos of shell splashes) and they're notably asymmetrical. I had misremembered, and/or gotten them confused with torpedo waterspouts, which look quite similar.

I still don't think that explains the discrepancy, as only 6 of the 20 hits are below the waterline. But I'm also not going to spend a lot of time digging around in the primary source data on this.