Today marks the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Leyte Gulf,1 probably the pinnacle of the Pacific War and by some definitions the largest naval battle in history.2 More than that, it was uniquely complicated and multifaceted: it included every form of naval warfare yet devised, from amphibious operations to carrier duels to the last-ever engagement between battleships. And above it all, Samar, that astonishing moment when a tiny force of American ships stood up against the mightiest fleet Japan could assemble and turned them back.

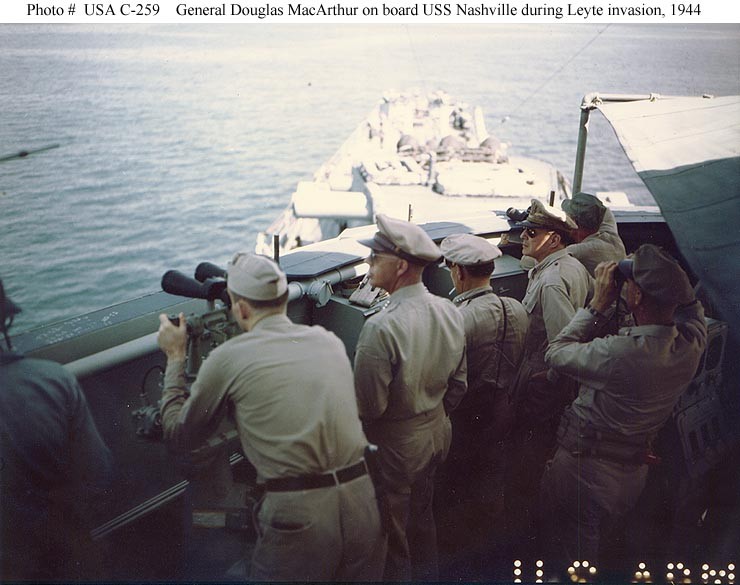

Douglas MacArthur and his staff observe the invasion of Leyte

Leyte Gulf was sparked by the American selection of the Philippines as the next stepping stone on the road to Tokyo, fulfilling Douglas MacArthur's promise to return and liberate it from the Japanese. The island of Leyte, in the center of the archipelago, was selected as the first target, giving the Americans a forward base from which they could spread out and liberate the rest of the Philippines. After extensive strikes from the carriers covering the operation, troops began going ashore on October 20th, initially in the face of only light opposition. The Japanese decided that the time was right to launch their fleet for the "Decisive Battle" they had been attempting to fight since the start of the war.

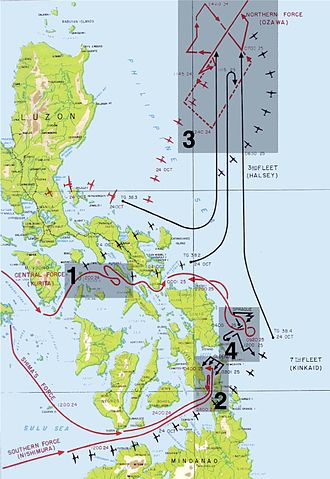

The action at Leyte Gulf

Their plan, as usual for the Japanese, was complicated. Their carriers, lacking air groups thanks to the casualties they'd taken in June at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, would approach from the north as a decoy to draw off the American carriers. With the covering force gone, two surface forces would approach from the west, passing through the Philippine archipelago and entering Leyte Gulf from the north and south and falling on the defenseless amphibious shipping there.

The Japanese Center Force under air attack

As usual, the plan fell apart pretty quickly. The center force, intended to enter Leyte Gulf from the north, was spotted by a pair of American submarines who managed to put two heavy cruisers on the bottom and damage a third enough that she had to turn for home. They then called the carriers, who sent in waves of planes that managed to sink the battleship Musashi. Unfortunately, they overestimated their effectiveness, and the rest of the force was essentially unharmed. Worse, it was reported that they were turning for home, and Admiral Halsey, commanding the fast carriers, decided to go after the Japanese carriers to the north. At the time, the only obvious problem was the loss of the light carrier Princeton to a Japanese bomb.

West Virginia firing during the battle of Surigao Strait

To counter the ships coming from the south, the battleships and cruisers that had been tasked with providing fire support for the landings were mustered in Suriago Strait. As the Japanese made their way north, they were attacked first by PT boats and then by destroyers. The PTs proved as ineffective as they usually did, but the destroyers sank the battleship Fuso and several destroyers while damaging battleship Yamashiro and heavy cruiser Mogami. Then it was the turn of the battleships, five of which had been at Pearl Harbor, and they took their revenge, annihilating the rest of the Japanese force.

Escort carrier Gambier Bay and two escorts make smoke at the start of the Battle off Samar

When Halsey headed north, he had issued a plan for his battleships (a group known as TF 34) to detach and cover the San Bernadino Strait, the path that the Japanese Center Force would have to take to reach Leyte Gulf. Unfortunately, this was only a plan, and it wasn't carried out, but unclear wording meant that Admiral Kinkaid, the commander of the amphibious force, thought that it had been. Secure in the knowledge that his back was covered, he had focused on the threat from the south. All of which meant that, at dawn on the 25th, nobody was expecting to see the Center Force from the decks of the escort carrier group known as Taffy 3.

Gambier Bay is straddled by shell splashes, with a Japanese cruiser barely visible on the horizon

Taffy 3 consisted of six escort carriers, screened by three destroyers and four destroyer escorts. They found four battleships and six heavy cruisers bearing down on them. The screen quickly made smoke and turned to engage a force that outgunned them by orders of magnitude, while the pilots flying from the carriers attacked with any weapon available. Thanks to the heroic resistance of the men of Taffy 3, Admiral Kurita, commander of the Japanese force, turned back and headed for home. Behind him, one carrier, two destroyers and a destroyer escort were sunk, and their crews had earned a place in the annals of naval history.

Japanese carrier Zuiho under air attack from Halsey's planes

During the night, Halsey had detached TF 34 and sent them ahead of his carriers, intending to follow up the dawn airstrike with a surface action. The airstrike itself was very successful, sinking three Japanese carriers, but before TF 34 could get within range, the messages from Kinkaid's beleaguered fleet reached Halsey. He promptly ordered his ships south, but it was too late. Kurita was already headed through the San Bernadino Strait and heading for home. The battle was essentially over, and the American Navy had managed to win complete control over the sea's surface.

St. Lo explodes after being hit by a kamikaze

Leyte was a pivotal battle, marking the final eclipse of Japan's attempts to control the sea. From then on, the only major sortie by their surface forces would be Yamato's suicide run on Okinawa. But the new threat that would bedevil the last 10 months of the war was already emerging. The first deliberate kamikaze attack was also made on October 25th, destroying the escort carrier St. Lo. Much worse was to come as the Allies battled through the Philippines and up the last stepping stones to Japan.

1 The battle took place over several days, but the climax was the 25th. ⇑

2 This is a surprisingly complicated question. Several ancient battles claim more ships and more personnel involved. I suspect that many of these numbers are exaggerated, although possibly not enough to salvage Leyte Gulf as the winner. It is uncontestably the largest in terms of displacement, and in terms of area fought over. ⇑

Comments

I think Leyte only wins the displacement cup if you count ships in the order of battle that weren't engaged. For a single battle with only engaged ships, Jutland might be a solid contender.

That probably depends on how we define "engaged". If we can count the carrier escorts, then Leyte Gulf shouldn't have any trouble winning. Keep in mind that ships got significantly bigger during the 1916-1944 period. The Queen Elizabeths, the largest ships at Jutland, were only about 75% of the displacement of the SoDaks, and a lot of the early dreadnoughts were smaller still, to the point that you're almost trading 2:1 against even the old battleships at Leyte Gulf.

Hmm, my definition of engaged is either firing/launching aircraft or being fired upon. Ozawa's tiny strike against Halsey was torn apart by the CAP before really getting to the fleet, so I think that many of Halsey's modern battleships and cruisers never even saw any Japanese units or fired their AA batteries.

Ozawa wasn't the only person on the Japanese side with airplanes. The plane that hit Princeton was from a land base, and clearly got close enough that they could shoot at her. There was at least one other land-based air raid, although I don't have details on how close it got to the task force.

MacArthur and his air chief Kenny were farsighted in their planning of bypassing those islands that they did not need to contest... but MacArthur had promised to return to the Phillipines and that he did.

The question is did he really need to? The Navy seemed to be doing quite a good job of destroying IJN capability and if the goal was solely to have a large staging area could not have Formosa been an option?

I realize that at first blush this seems like a rather odd question, but the Navy seemed to be doing rather well in exactly what they had planned at the outset of the war--sail across the Central Pacific and destroy the IJN and the merchant shipping that supplied the home islands.

Could the Philippines just been one more of those areas like China, Singapore, etc. that had significant Japanese garrisons at the cessation of hostilities?

In early 1944, Formosa was where Nimitz wanted to go, and the original plan was to bypass the Philippines in favor of it and the coast of China. This fell apart due to the major Japanese offensive in China, which pushed the KMT away from the coast. (There's a lot of discussion of this in Morison's book on Leyte.) Overall, it was probably the right move. The bigger gamble was moving from Mindanao in December to Leyte in October on five week's notice. But yes, it could have been, and at one point, Mindanao was the only piece scheduled for liberation to serve as a base for pounding down the rest.

I believe Borneo is usually held up as an invasion that wasn't contributing at all to the war and was done just for political reasons.

In retrospect of course, we know that with the Manhattan project succeeding that means the entire island hopping campaign was "not needed" and the Allies could have just held their ground at Hawaii and Darwin and waited until the nukes were ready. But that is only feasible with time-traveller levels of foresight so we don't need to go that far.

I think not, on two levels. First, the island-hopping campaign against Japan was necessary to provide the bases. The Marianas were taken in June 1944, and nothing the US had had remotely the range to reach Japan from bases held during 1942. (Except China, but staging the nukes through there is dubious for obvious reasons.) Second, it created the conditions for the surrender. The Japanese were almost crazy enough to not surrender IRL, and in an alternative world where they still controlled most of their conquests, they'd almost certainly chose to fight on.

I see a couple difficulties as well with the "just wait until the nukes were ready" scenario even if, as you mention Doctorpat, the crystal ball would have been clear enough to see that these were going to be viable weapons.

The first, as Bean points out, is that we still would have needed to have concurrently developed a delivery system (aircraft presumably) that had the range to strike. Gaining a close in base/bases would have still been necessary.

The second is that the allies destroyed the defences that allowed Tibbets and crew to fly in single ship. Japanese fights did engage B-29s. Their success might have indeed been sporadic, but if the Japanese had even more years to consolidate their gains and presumably strengthen home island air and sea defenses it would have been tricky.

We know that one of the Japanese weaknesses was home island air defense, but one would think that at some point they would have tried to cover that vulnerability. However...they really had believed for so long that no enemy could come close so who knows exactly when the light would have come on.

Obviously I could be completely wrong in my thinking, but that is what prompted my mulling over if re-taking the Philippines was a necessary step. Real estate was a necessary element of getting within striking distance of the home islands but as with all real estate questions it boils down to location, location, location.

In a similar vein to Neal's comment, if your plan is to win with nukes then it makes sense to use your fleet assets (which you don't need for victory) to distract and attrit your opponent's air capability. By keeping the Japanese engaged at sea you disguise your intentions, and encourage them to waste resources (particularly oil) on things besides homeland air defense.

Another big problem with "sit by until we win with nukes" is that it doesn't work from other standpoints. Either they say "we have a secret weapon that will win the war in a few years" (Japan pours lots of money into air defenses) or Roosevelt is swept from office in 1944 by Dewey on the grounds that he's an idiot who can't manage the war. Secret weapons work best when nobody suspects their existence, which means acting the way you would if they didn't exist. The US managed to win the war via conventional means before delivering the last shock with The Bomb.

On Formosa vs the PI, taking either one would have allowed the US to completely sever Japan's SLOC to Borneo, Malaya, and the DEI. Not much advantage to either choice on that score. There were some advantages to selecting the PI over Formosa, like useful proximity to US LBA in New Guinea (especially for the originally planned landings on Mindanao) and the presence of a friendly, helpful civilian population, which IMO justified that choice on purely military grounds - i.e. without reference to the idea of "salvaging America's (meaning MacArthur's) honor."

@Philistine

Points well made Philistine. I overlooked both the New Guinea factor as well as the helpful population of the Philippines.

New Guinea is easily the most overlooked campaign of the war (at least that the Americans fought in). It was a brilliant performance, but overshadowed by what was going on in the Central Pacific. I really should write about it more. (It featured in my amphibious warfare writeup.)

It appears that RV Petrel went straight from Midway to Leyte, as the team have just announced the discovery of the wreck of what they believe to be Johnston. This is excellent news.

@neal

the japanese air defenses hadn't really been destroyed. they made a conscious decision not to attack the bombers to preserve gas and aircraft for resisting the invasion. They were helped along in this fact by the fact that the ability of Japanese aircraft to engage B-29s was fairly limited.

I agree that sitting out till the nukes came wasn't in the cards, but the US probably could have gotten by spending half what it spent on the pacific war, poured the rest into invading Europe a lot sooner and left everyone a lot better off. Germany first was a commitment followed more in word than in deed.