One thing that I don't often talk about is what life was like aboard a battleship. This is because I prefer the technical side of naval history, but doesn't mean I should totally ignore the human aspect of these ships. So let's take a look at what life aboard Iowa looked like, mostly during WWII but also during the 80s commission.

A corridor aboard Iowa1

The first impression most people get when they come aboard is one of an endless maze of twisting passageways, all alike. The walls, known as bulkheads aboard a ship, are gray, the doors mostly have really high sills called knee-knockers,2 and the stairs are as close to being ladders as they can be and not actually be ladders. They're called ladders anyway, maybe because it's traditional, maybe just because the Navy prefers to confuse outsiders. The overheads are filled with pipes and cables, and the bulkheads are thin and made of metal. There's all sorts of equipment hanging on them, fire-fighting gear, breathing apparatus, water fountains, electrical distribution equipment, and so on. Things are exposed so they can be gotten to if they break.

One of Iowa's many steep ladders

If you’re over 6’ tall, you get very used to ducking, and even shorter people have to watch their heads at times. Moving through this environment quickly and without injury is an art form. The ship was clearly designed to fight, and not to be comfortable for the crew. Some compartments have random things running through them, tubes for 5” gun ammunition or director wiring. To help the crew navigate, there are painted signs known as ‘bullseyes’ that give the "address" of the compartment.

Berthing compartment used by the Massachusetts Living History Group3

However, Iowa was one of the nicer places to be assigned for an enlisted man. I started this post by looking at my 1940 Bluejacket’s manual, and it has large sections on sailors washing their own clothes and the use of hammocks. Neither of these were a problem on Iowa. There was a laundry, and each man had his own bunk, along with a locker for his gear. Some of these bunks were four and five levels high, which did not exactly leave a lot of personal space, and definitely gave no privacy to the occupant. The top bunk was prized, as it was by far the most pleasant in heavy weather. There was no chance of someone above being seasick.

Bunks aboard Iowa today

Even a ship as big as Iowa was cramped. She was designed for a crew of 117 officers and 1,804 enlisted men, but in 1945 she had a complement of 151 officers and 2,637 men. Some men had to bunk in their duty spaces (even inside the turrets), although the Iowas were relatively spacious compared to their predecessors of the South Dakota class. When I visited Alabama and Massachusetts, I was amazed at how cramped they were.

The mess line on Iowa

Food came from the mess deck, which looked remarkably like a traditional cafeteria on land. There were lines on each side of the ship where the cooks dispersed whatever was on the menu that day. Four meals were served, breakfast, lunch, dinner, and mid-rats. Mid-rats was a midnight meal for those on duty overnight. The men ate at long tables, which, unlike on other ships, did not have to be stowed to allow men to hang their hammocks. There were two ice-cream machines, which were, according to the Royal Navy (whose living conditions were considerably more spartan) the most important piece of equipment onboard any US Navy ship, as the ship didn’t go to sea if they weren’t working.

The enlisted mess aboard Iowa

The crew in WWII consumed 7 tons of food per day: 1.5 tons of fresh food, 2 tons of frozen food, and 3.5 tons of dry food. The total bill? $1,600 at the time, which is over $20,000 today. A total of 834 tons of food was stored aboard, a third of the weight of a typical destroyer, and the ship could stay at sea for 119 days before resupply. Iowa was designed in an era before modern material-handling practices, and even in the 80s, supplies had to be loaded aboard by hand, using chains of men to pass them hand-over-hand.4

Cigarettes being loaded aboard Missouri, 1944

The battleships are often described as “cities at sea” and this is not a bad description. They had tailors, cobblers, barbers, a printing shop, a library, a dentist and a full hospital onboard. But they were cities populated exclusively by men, and mostly young ones. US Navy ships were and are dry, although that didn’t stop some men from cooking up alcohol illegally. A 1980s crewman told me that they used to steal cases of apple juice, puncture the tops, let them ferment for a while, then put them in the freezer to distill. Another popular (though illegal) hobby was gambling, particularly as there was no real place to spend their money while at sea. Men caught doing these things would be sent to mast, where the Captain could impose a non-judicial sentence, usually extra duty, but occasionally confinement in the brig on bread and water and/or loss of rank.

A boxing match aboard Iowa, 1944

For legitimate recreation, popular methods included movies (the ship was assigned four different movies, and would often play all four in different locations every night), boxing, and writing letters home. Mail is vital to the morale of men in combat, particularly in the days before phone calls home became possible, and the Iowa has a post office on 2nd Deck.

The Post Office

In the 80s, some refits were carried out to improve habitability. New 3-high racks were installed, with storage under the mattresses where the decks were high enough. Each bunk has a curtain to finally give the crew some privacy, a reading light, and a small locker for an oxygen breathing apparatus. I’ve spent the night in one, and they’re pretty comfortable, although you do have to be careful not to hit your head if you’re in the top bunk, and getting in and out is difficult.

The berthing space for the GM Division5

A sailor’s day was defined by his watches. A watch is a period when a sailor is on duty. This usually means that he has an active job in running the ship. Depending on his job, he might be manning a lookout station, manning a gun, or deep in the ship, monitoring the boilers or turbines. How much of the time he spent on this has proved unexpectedly difficult to research, as the two Bluejacket’s Manuals I have from WW2 (1940 and 1943) seem to indicate that the usual schedule was to have two watches, port and starboard, and alternate them. This was indeed common in war zones, but it places a great strain on men, and I believe that large portions of the time, the watch rotation was less strenuous. Each watch was 4 hours, except for a pair of ‘dog watches’ that were two hours each, to rotate the watches and make sure that nobody got stuck with an unpleasant watch, like midnight to 4 AM, long-term.

Holystoning the deck of the New Jersey, 1943

Of course, it wasn’t simply a matter of standing watches. There was lots of other work to do, too. There was a great deal of work involved in keeping a ship running. Surfaces had to be painted, and machinery had to be maintained. The deck had to be holystoned to clean and whiten it, which involved taking a boiler brick, breaking it in half, then attaching a handle. The deck division6 would line up across the ship, 20 men across. Each board got 20 strokes with the holystone, and then the line would advance. This was done barefoot, which made any mistakes painful.

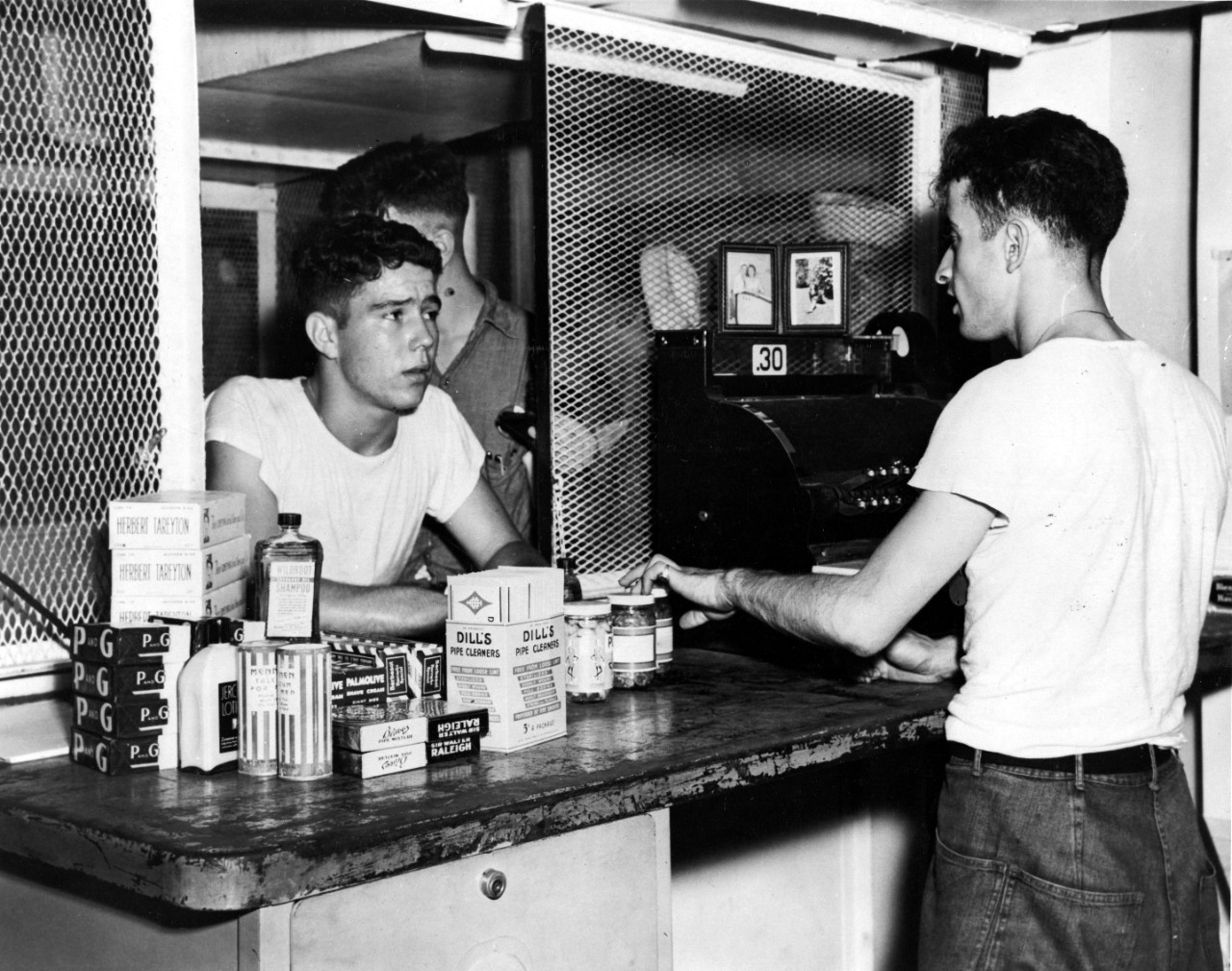

The store aboard Missouri, 19447

For men who did not have to stand watches, the day began at 0530, by sweeping down the ship. Breakfast was at 0730, and work resumed at 0815, running until dinner at 1800 with an hour for lunch. Some work might be done after dinner, although most of that time was for recreation.

Sailors man a Mk 51 director, 1944

When General Quarters was called, everyone, regardless of status or current task, would go racing to his battle station. Many had GQ stations related to their "day jobs", although cooks, clerks, and the like were expected to contribute. A battleship was an incredibly labor-intensive machine, and they would pass ammunition, talk over the sound-powered phone circuits, and provide manpower for damage control. In peacetime, GQ drills varied in frequency with the interest of the Captain in battle-readiness. In wartime, they happened frequently, as well as being done in deadly earnest when action threatened. The USS Washington, in four years in commission, most of them at war, counted over three thousand calls of General Quarters. Sometimes ships would stay at GQ for hours or days on end, although this was tremendously wearing on the crew.

A mass aboard Iowa, 1944

I haven't covered every detail of life aboard Iowa. That would take a full book, and it's not one I have or intend to write. I do intend to talk more about the men that turn hunks of steel into warships going forward, but probably in a somewhat broader way.

1 Thanks to BBgate for providing the photos to illustrate most of this article when my archives turned out not to have appropriate images. ⇑

2 There are two reasons for these. First, they impede the flow of water, which can get in in bad weather or due to damage. Second, smaller openings are better structurally, which is why you see them even high enough in the ship that water will only reach the area if the ship is actually sinking. ⇑

3 My photo from the Massachusetts. Their Living History Group was very impressive. ⇑

4 For the record, "men" is correct here. The USN did not send women to sea aboard warships until after Iowa was retired for the last time. The only cases I know of of women aboard long-term were the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders and one female trials engineer, who was given the captain's in-port cabin, where Roosevelt had stayed. I'm sure there were a few others, but none as an official part of the ship's crew. ⇑

5 GM Division was responsible for the new weapons, such as Tomahawk, Harpoon, and CIWS ⇑

6 The men responsible for operation and maintenance of the topsides of the ship, including the decks, ropes, and so on. ⇑

7 There are quite a few wonderful online photos of life aboard Missouri in 1944. I can't explain the bad taste of whoever sent the photographer or chose to put those pictures online over a similar set from Iowa. ⇑

Comments

The more things change, the more they stay the same. I was stationed aboard USS Ramage (DDG-61) for a time, and other than being slightly more cramped, most of the interior shots from Iowa could almost as easily have been from Ramage. Our bunks were, naturally, of the later variant (as on post-refit Iowa), and I'm glad of it: that's a huge increase in comfort relative to the old ones. Of course, the standard call for reveille still says "all hands heave out and trice up", even though you can't trice up those new-style racks, and most sailors don't even know what that term means anymore. (Only the very saltiest chiefs and warrant officers have ever served on a ship where you could trice up the racks, by now: even the comparatively hoary Ticonderoga CGs and the earliest CVNs have the new-style racks and always have.)

AIUI, the Iowas, even after the refit, were considered relatively uncomfortable by 80s standards, although I do remember that the Burkes saw habitation given a fairly low priority. I've only been on one Burke, and didn't get to spend a lot of time inside. There's a definite kinship among the interior of all reasonably modern warships. America was fairly familiar, although she was new and shiny and had big corridors for loaded Marines.