I’ve written quite a bit on the history of battleship design, but I haven’t spent much time on the use of the early battleships. This is a gap I intend to close, by looking at the (surprisingly few) clashes of ironclad and pre-dreadnought battleships.

The Battle of Lissa

The first of these was the Battle of Lissa in 1866, famous mostly for giving most of the world the impression that the ram was an effective weapon of war. It was part of the Third Italian War of Independence, which was fought in parallel with the Austro-Prussian War, in an attempt by the Italians to wrest Venice from the Austrians. The fleets met near the island of Lissa, now known as Vis, off of modern-day Croatia, where the Italians were attempting an amphibious landing.

Konteradmiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff

The Austrians, under Konteradmiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, were heavily outnumbered, with 7 broadside ironclads, 7 large wooden ships, and 12 gunboats. The Italians, commanded by Count Carlo di Persano, fielded 11 broadside ironclads, one ironclad turret ram, 10 large wooden ships, and 4 gunboats. Neither side’s ships were well-designed or well-built, and both suffered from large numbers of untrained men aboard their ships. Persano constantly complained and asked for more ships and guns, while Tegetthoff trained vigorously. An early encounter off the Italian base of Ancona was rather comic, as Tegetthoff tried to entice the numerically superior Italians out, and Persano vacillated until the Austrians got bored and went home.

Carlo Pellion di Persano

The Italians had finally gone to sea, appearing off Lissa and launching their attack on July 18th, although calling it an attack is being generous. Some of the Austrian batteries had been silenced by the 20th, when Tegetthoff appeared, but Admiral Albini, commanding the wooden ships, had done nothing at all, and one of the Italian ironclads had suffered over 50 wounded in a duel with Austrian guns, taking it out of the coming battle. Worse, Persano had allowed his ships to be scattered around Lissa and had failed to maintain a proper watch for the Austrians.

Tegetthoff split his fleet into three divisions, each a wedge pointing at the Italians. The ironclads were the lead division, followed by the wooden frigates and their single two-decker,1 Kaiser, of 2nd Division, and finally the gunboats in the rear. Persano ordered his ironclads to form a line abreast, facing the Austrians, backed by the wooden ships under Albini. Albini ignored the order and sat the battle out, going a long way to even the odds, already tilted by the fact that two of the Italian ironclads were at least two hours away. Persano then continued to shoot himself in the foot, ordering his fleet to switch to line ahead, the classic naval formation of the age of sail, and adding to everyone’s confusion.

A map of the situation at the beginning of the battle

Amazingly, that was not his biggest mistake. He then decided to switch his flagship from the broadside ironclad Re d’Italia to the turret ram Affondatore, in hopes of commanding from outside the line of battle, and presumably of using Affondatore as a mobile reserve. He then failed to notify everyone of this change of flagship, which meant that the rest of the fleet spent the battle watching Re d’Italia instead of Affondatore. As Re d’Italia slowed to launch boats, a gap opened in the Italian line, just as Tegetthoff reached battle range.

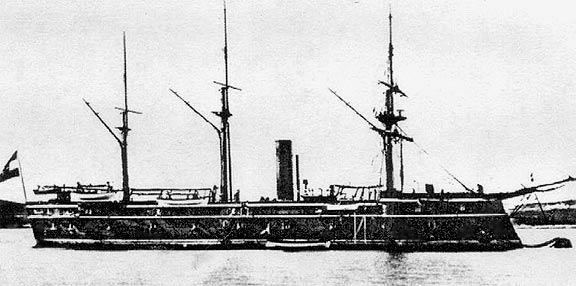

Italian flagship Affondatore

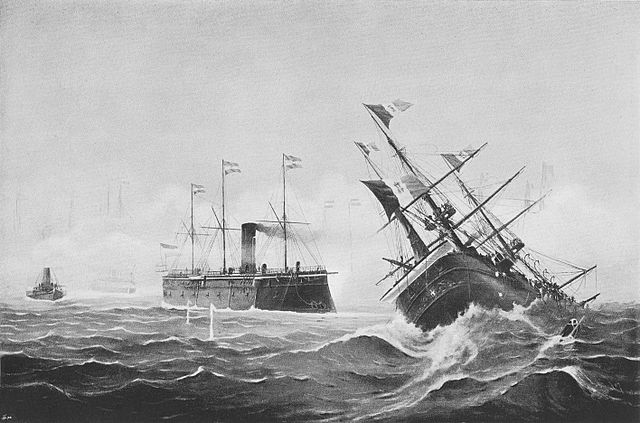

The Austrians passed through the gap, and the battle quickly became a farce, shrouded by the dense smoke produced by gunfire and steam engines. The only saving grace was that the Italian ships were light grey and the Austrian vessels black, making identification easy. The Austrian 2nd Division headed for Albini’s force, but was intercepted by three Italian ironclads. The Austrian 1st Division likewise faced a smaller group of three ironclads, while Affondatore and the rest of the Italian ironclads ran around in confusion.

Tegetthoff had decided, based apparently on American Civil War experience, that the ram was the most effective weapon he had, and had ordered his ships to ram the Italians. This was even less effective than his gunfire, with numerous attempts by the ironclads to ram the Re d’Italia failing, until one finally carried away her rudder. Tegetthoff’s flagship, Ferdinad Maximilian, then rammed the Italian vessel, helped by poor shiphandling on the part of the Italian captain.

Re d'Italia Sinking

Re d’Italia quickly sank, taking over two-thirds of her crew with her. Another Italian ironclad, Palestro, was badly damaged by ramming and driven off. On the other side of the formation, the battle between the Austrian 2nd Division and the Italians was confused. Persano had attempted to ram Kaiser, but missed, and Kaiser had then rammed the Re di Portogallo, leaving her figurehead in the side of the Italian vessel. The Italians attempted to rake her with fire, but either missed or failed to load shells.2 Affandatore reappeared, but again failed to ram Kaiser. Confusion among the Italians allowed Kaiser and the rest of 2nd Division to escape.

The Italians still outnumbered the Austrians, and their wooden ships were totally unengaged. However, low morale and dwindling supplies of coal and ammunition lead Persano to order a withdrawal. Palestro was burning badly, and blew up while under tow back to Italy. Tegetthoff entered the harbor of Lissa in triumph, despite the damage to Kaiser and the ironclads of his fleet.

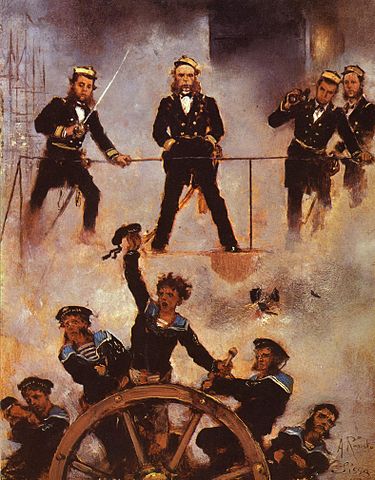

Tegetthoff and staff during the battle

Persano was tried by the Italian senate and stripped of his rank for incompetence. Albini was merely relieved of command. The war ended in defeat for Austria on land, but the battle had long-lasting effects on naval warfare.

Lissa fell into a brief period where the capability of armor plate to resist shot was significantly greater than the ability of guns to penetrate it. This would not last long, but due to ‘combat experience’ showing that ramming was effective, most warships for the next 40 years were fitted for ramming.3

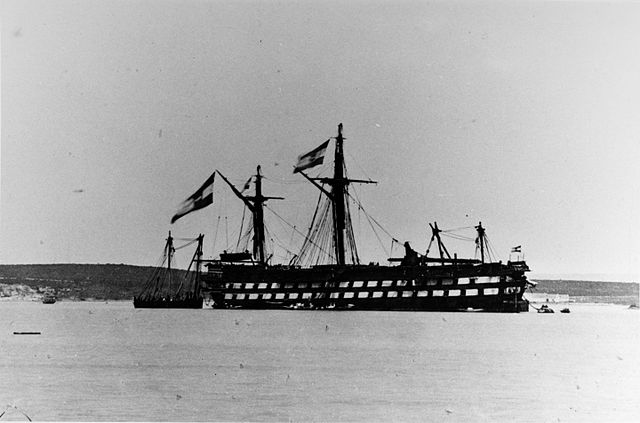

Austrian two-decker Kaiser under repair off Lissa after the battle

Despite Tegetthoff’s orders to ram, only one successful ramming was conducted, with two or three more attempts resulting in glancing blows. The Italians, despite having a ship explicitly designed for ramming, were totally unsuccessful, although Persano may be to blame for that, and Ferdinand Max was damaged by her attempts. Conventional wisdom says that ships under way were maneuverable enough to dodge most ram attempts, and that in the long run, rams were most effective in making collisions at sea worse, most notably the sinking of HMS Victoria after her collision with Camperdown. The concept also produced several rather unusual and useless ships, designed with the ram as their primary weapon, as late as the 1880s.

However, Stephen McLaughlin, in his Russian & Soviet Battleships, suggests that conventional wisdom is at least partially wrong. The poor visibility that was a repeated problem at Lissa would have been repeated at any naval battle through the 1880s, due to gunsmoke and coal-burning engines. Combine this with low gun ranges and slow-firing guns, and ramming becomes a possibility, particularly if both sides are trying to do it. The Russians actually conducted a full-scale trial of ramming in 1868 using two gunboats fitted with bumpers, and discovered that it was possible, although the blows were usually glancing ones.

The next use of ironclads in battle was off South America, in a series of naval actions virtually unknown to the wider world, but fascinating none the less.

1 This meant the guns were on two gun decks, one above the other, while frigates had a single deck of guns. There were three-deckers, but they tended to be flagships of major naval powers. ⇑

2 This was not an isolated occurrence. Crews failing to load shells happened more than once during the battle. ⇑

3 Strictly speaking, the period was already over. Guns capable of penetrating armor plate were becoming common, but the only ship at Lissa which carried them was Affandatore, whose gunnery problems masked this. Wars are often fought by obsolete ships, and Lissa is far from the only case where their irrelevant experience altered ships on the drawing board. ⇑

Comments

You've got the wrong photo of AFFONDATORE. That's how she looked after her (second) reconstruction in 1888-1889. She looked more like this at Lissa: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Affondatore.jpg/300px-Affondatore.jpg

Either side's armor was penetrable by modern (ie, large, heavy rifled guns or humongous smoothbores). There were ample examples of armor penetration in the American Civil War, and both the 8"/150pdr Parrot rifles and the XV-inch Dahlgren smoothbores would have done the job. So would the 7 and 8" rifled muzzle loaders the Royal Navy was beginning to arm their ships with.

Looking at the armaments of the two respective flagships, though (setting aside the silliness of switching flags before the battle, especially to a turret ship), both fleets are drastically under armed. ERZHERZOG FERDINAND MAX had nothing more than a 48pdr, and RE D'ITALIA had a mix of 6.5" rifles and 72pdr smoothbores. Only AFFONDATORE was carrying the necessary weapons (300pdr smoothbores) to punch through.

I've fixed the photo. Thanks for pointing that out.

Re armament, I'll more or less stand by my statement. As Norman Friedman said on the 8" gun after the Spanish-American War, “Throughout the history of modern warships, however, combat experience, no matter how objectively irrelevant, has had enormous impact.” The warships that actually fight wars are almost always the product of the previous generation of technology. There was a very brief period in which armor could decisively beat guns. The warships that fought at Lissa were all from that period, except for Affondatore (sort of).

@John Schilling "Isn’t there sort of a contradiction between fighting an “independence war” and already having a navy with eleven battleships? A quick check confirms that most of Italy had been independent since the Second Italian Independence War"

Consider that we also had a Fourth Independence War, from 1915 to 1918.

The Third and the Fourth should have probably called 'Unification' wars, but if the First and the Second worked so well, why change the name? :-D