The large-scale transport of passengers across the seas is a surprisingly recent phenomenon. Until the 19th century, there were no scheduled services, and while the horrors of the slave ships are reasonably well-known, conditions for free passengers were little better during the 18th century, with the maximum number crammed in belowdecks with poor food and minimal sanitary facilities during passages that could last weeks.

Packet New York of the Black Ball Line

The first major stride was the establishment of regular service across the Atlantic with the founding of the Black Ball Line in 1817. Black Ball promised to sail once a month on a scheduled day from New York and Liverpool, as opposed to the previous practice of waiting until a full load of cargo could be put together. While passage times for the sail-powered ships were still unpredictable, passenger accommodations were at least slightly better for voyages which averaged 25 days eastbound and 43 days westbound due to the prevailing winds, and Black Ball soon had a host of imitators to contend with.

Great Western battles heavy seas

Some of these companies were drawn to the steam engine, which offered the potential of not only faster transits, but also significantly more reliable schedules, a major boon to an increasingly competitive world. The first steamship to reach New York direct from Britain was the converted Irish Sea packet Sirius in April 1838, although she was only a day ahead of the Great Western, brainchild of famous engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, intended as a spinoff of his Great Western Railroad. Great Western had left four days behind Sirius, and came into New York with her bunkers half full, while Sirius had been forced to burn her spars to make the voyage. The next year, the British government issued the first transatlantic mail subsidy to a company run by Samuel Cunard, whose ships became famed for their reliability. An American attempt at competition, the Collins Line floundered on high operating costs and several disastrous shipwrecks, most notably that of the Arctic in 1854, the most famous liner disaster for half a century.

Mauretania in Dazzle Paint during WWI

During the second half of the 19th century, steam engines got more efficient, and passengers liners became common, not only on the North Atlantic run, but worldwide, as the Suez Canal and more efficient steam engines opened steamer trade between Europe, India and the Far East. The North Atlantic remained at the center of the liner world, though, as companies sought the coveted Blue Riband, the informal award for the fastest passage, while also competing to offer the most luxurious accommodations for their first-class passengers. Speeds rose from 10 kts in 1838 to 15 kts in 1873 and 20 kts in 1889, finally leveling off two decades later with the Cunard liner Mauretania's 26-kt run. Bigger and faster ships lead to an explosion in oceanic travel, and liners catered to all social classes, with palatial areas for first-class passengers and conditions in steerage only made better than those of sailing ships by legislation in 1839 mandating that the ship provide food and a specific amount of space to each passenger.

Queen Mary off New York

The second decade of the 20th century brought disaster to the massive ships that crossed the North Atlantic, first in the loss of a vessel on her maiden voyage to an iceburg and more importantly when Lusitania, sister to Mauretania, was sunk by a German U-boat in 1915, ultimately drawing the US into the war. Postwar, the liner competition lapsed for a decade, then came to life again amid intensifying national competition, represented by vessels such as the German Bremen, the Italian Rex and the French Normandie, the first vessel to take the Blue Riband at more than 30 kts. The British responded with Queen Mary, the final prewar holder of the riband, built despite the depression and a valuable vessel during WWII, when she carried hundreds of thousands of troops around the world, usually sailing unescorted thanks to her high speed.1 Normandie was to be converted for similar duties, but caught fire and sank pierside in 1942.

SS United States

Postwar, the days of the ocean liner were numbered. WWII had seen massive advances in aviation, and aircraft took an increasing fraction of passengers making long-distance voyages every year. The Blue Riband was taken in 1952 by the SS United States, at an incredible 35.59 kts. She was not the last vessel built for the North Atlantic, but she was the last to push naval architecture forward, thanks to a subsidy from the US government, who planned to turn her into a troopship in wartime. She still holds the Blue Riband today.2 In 1958, aircraft overtook liners in passengers carried across the North Atlantic, and the Boeing 707 entered passenger service, soon to consign the ocean liner to the pages of history, as it was cheaper, faster, and more convenient.3

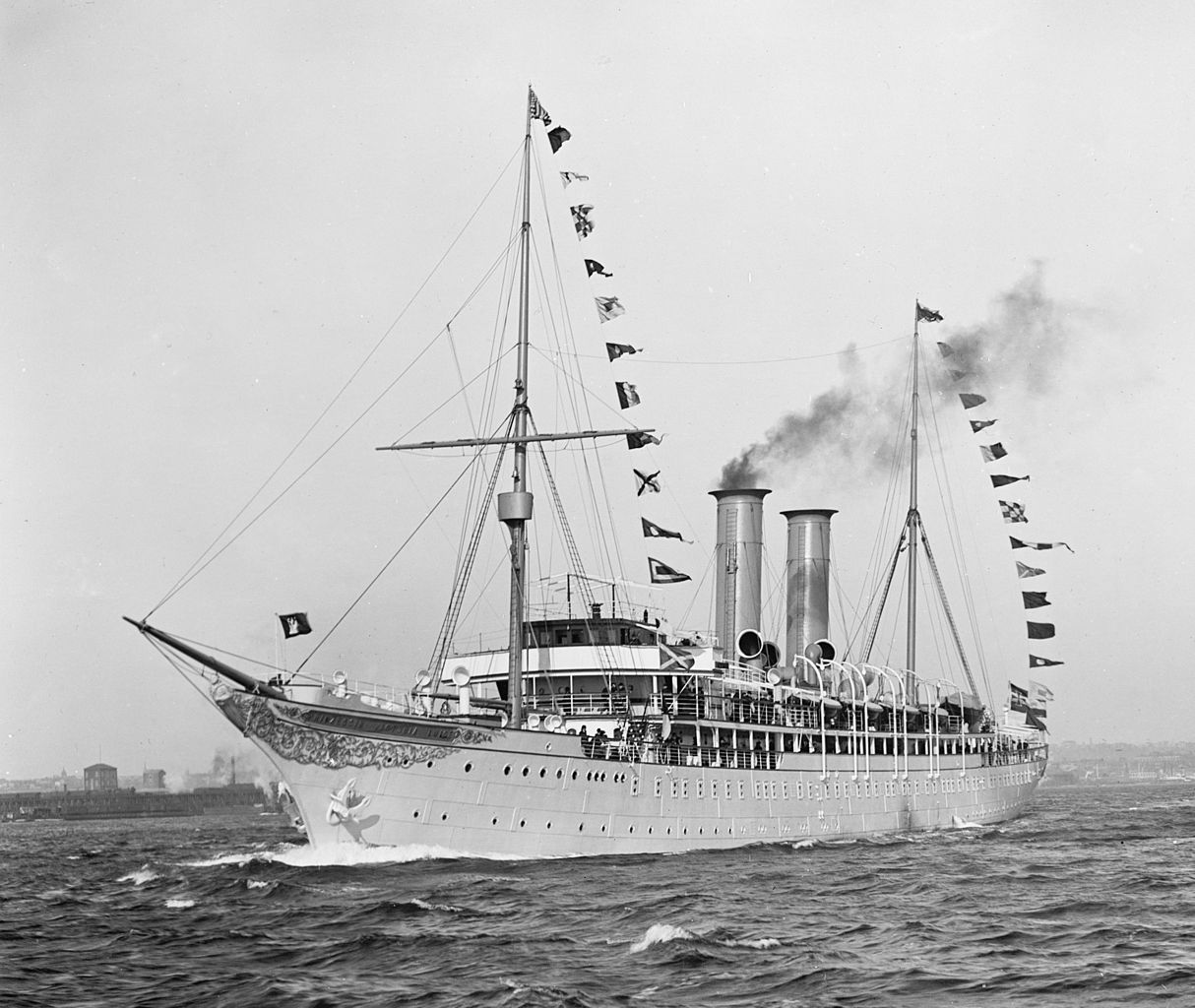

Prinzessin Victoria Luise

Humans have always been drawn to the water for recreation, and the idea of using a ship to see exotic sights is an old one, at least for the very rich and their private yachts. During the late 1800s, as passenger vessels improved, opportunities opened for less wealthy passengers, as European shipping lines began carrying passengers to the Mediterranean in the winter months and to the coast of Norway in the summer. These early cruises were carried out by conventional ocean liners, but the first dedicated cruise ship, Prinzessin Victoria Luise, was launched in 1901 with 120 first-class cabins to cater to the very wealthy, and soon proved a huge success. The development of cruising was disrupted by WWI, and later by the depression, although Prohibition saw "booze cruises" into international waters become popular in the US.

Liner-turned-cruise ship Canberra, which played a major part in the Falklands War

Cruising really began to take off after WWII, when owners of ocean liners rendered surplus by transoceanic air travel converted them to cruise ships. They found a ready market from those who wanted to visit new places, or just to go somewhere warm and sandy in comfort. By the late 60s, purpose-built cruise ships began to enter service, equipped with pools, broad decks, and air conditioning for the comfort of passengers in areas like the Mediterranean and Caribbean, the later of which quickly became the epicenter of the cruise industry. They were also slower than their ocean liner brethren, and at least initially smaller as well, although surging demand soon drove up sizes again. The industry as a whole has experienced incredible growth, with passenger count growing an average of 6.63% yearly since 1990,4 and at least 9 new ships coming into service every year since 2001. Today, the largest cruise ships, Royal Caribbean's Oasis class, carry approximately 5,400 passengers and provide amenities including 4 swimming pools, waterslides, 20 dining venues, a skating rink, and walls of hideous balconies on a ship the size of a Nimitz class carrier.

Oasis of the Seas

While the ocean liner has been supplanted by the airplane for long-distance travel, passenger travel on the seas, now for pleasure, remains an important sector of merchant shipping. On shorter routes, passenger ferries are common in some parts of the world, most notably in the waters around Europe and the Far East. But airplanes are not particularly good for hauling large amounts of cargo, so the vast majority of international trade in goods continues to go by sea. We'll take a look at that next time.

1 It was during this service that she set the record for the most people ever transported on a single voyage, at 16,683. Today, she's a hotel and mediocre museum ship in Long Beach, California. ⇑

2 This is disputed, as there have been faster transatlantic crossings by various vessels, but in my opinion, the Blue Riband belongs to ocean liners, not to ferries running the North Atlantic for purposes of a record. ⇑

3 The only remaining ocean liner is Cunard's Queen Mary 2. Although she often functions as a cruise ship, she was built to liner standards and still sees service on transatlantic voyages. ⇑

4 Figures as of February 2020, and yes, the cruise industry was particularly hard-hit by COVID-19. ⇑

Comments

I'm not sure any ship type in history can match the modern cruise ship for sheer ugliness.

I'd say it's not quite as hideous as some of the French pre-dreadnoughts, but they're definitely on the same level as Fuso. I always felt a bit bad for them when they sailed out of LA, because they had to go right past the most beautiful ship ever built.

Perhaps I denounce myself with this, but I actually rather like the steampunk-esque aesthetic of the French pre-dreads, and there's something oddly compelling in the ugliness of pagoda-masts.

I can sort of understand that. They're both ugly in interesting ways. But a cruise ship is just ugly for boring reasons, and it doesn't help that so many of the old ocean liners were beautiful vessels.

@Directrix Gazer & bean

the Juan Carlos class begs to disagree:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5c/08.05.11LasPalmas_001.JPG

Also Directrix, we still need to get together for lunch sometime, you should shoot me an email from an account you check.

@Cassander

0.0 I... I stand corrected.

While Juan Carlos isn't going to win any beauty contests, I don't think she's particularly ugly. She's just very plain, with a few bad angles.

She looks alright from some angles, but bow-on she's as hideous as anything that's ever floated, by my lights at least. It's the asymmetry combined with the block-of-cheese-carved-by-an-indifferent-elementary-schooler contours.

In general, I think asymmetric ski-jump bows are awful-looking. The Queen Elizabeth class are another good (bad) example.

I'll definitely agree that ski-jumps are ugly. The only ships with them that looked decent were the Invincibles, and they were retrofitted with the ramp. And yes, adding a ski-jump to a car carrier (which is what the hull reminds me of) isn't going to produce a good-looking ship, it's at least functional. Whereas most cruise ships have no good angles at all.

There are still a couple of elderly ex-ocean liners in service as cruise ships- Marco Polo, built in 1965 as Aleksandr Pushkin for the Soviet Baltic Shipping Company, last made a liner voyage in 1979 or 1980 between Leningrad and Montreal.

Astoria, built in 1948 (!) as Stockholm for the Swedish America Line, was involved in an infamous 1956 collision with the Italian Andrea Doria and seems to have last made a liner voyage in 1959, before spending the next 25 or so years as a cruise ship owned by an East German trade union...

@cassander

Madrid, 2003: "Hey you got the sketches for the ship ready to show?"

"What ship?"

"The new amphibious assault ship & aircraft carrier we're proposing"

"It's both? Like two ships, but together?"

"YES. C'mon, don't play around, the presentation is in like an hour, we need to get those visuals printed."

"Umm, yeah... Just give me a few minutes, I have to make some minor adjustments."

The grammar police found a typo.

"The industry as a whole as has".

I think that an aspect of the (extremely sad) decline of ocean liner is also the social conditions of the late 60s/early 70s, at least here in Italy.

The last two Italian liners ever built, Michelangelo and Raffaello (which stand more than a fighting chance in a competition for most beautiful thing to ever touch the seas, IMHO), where plagued by constant workers' unrest. The Società Italia had to have two full crews for each ship, so that the sailors could rotate every 2 weeks. That worked sort of well until they couldn't put more than 400 passengers on each trip, and started having trouble to make ends meet. The direction tried to negotiate to reduce the size of the reserve crew, and the unions went on strike, demanding pay raises. In the end they were saved by the government, which started subsidizing the two ships, scared of the consequences of the mass laydown of specialized workforce (the liners employed 3000 people directly, plus many more indirectly, in Genova, which was already an hotbed of political unrest and terrorist activities). They declared strikes with almost no warning for every perceived injustice, for example once a departure was delayed 48h because the crew were given tap water instead of the bottled mineral one of the passengers.

In the end they were still forced to sell them to Iran, which planned to use them as floating barracks (for extremely lucky soldiers, I guess), but instead ended up being abandoned after the revolution and firebombed by the Iraqis during the war.

I don't know about that. Container ships won't win any beauty contests either.

Car carriers are more ugly to me than cruise ships.

But then, I like to cruise.