Military pricing is famously arcane, even compared to the rest of military procurement. It's much more difficult than you might think to figure out how much an airplane or a ship actually costs, particularly as there are several different ways to measure it, each of which have their own uses. This gives interested parties endless scope for twisting figures to suit their ends, although some knowledge can at least let you ask the right questions about the numbers they give you.

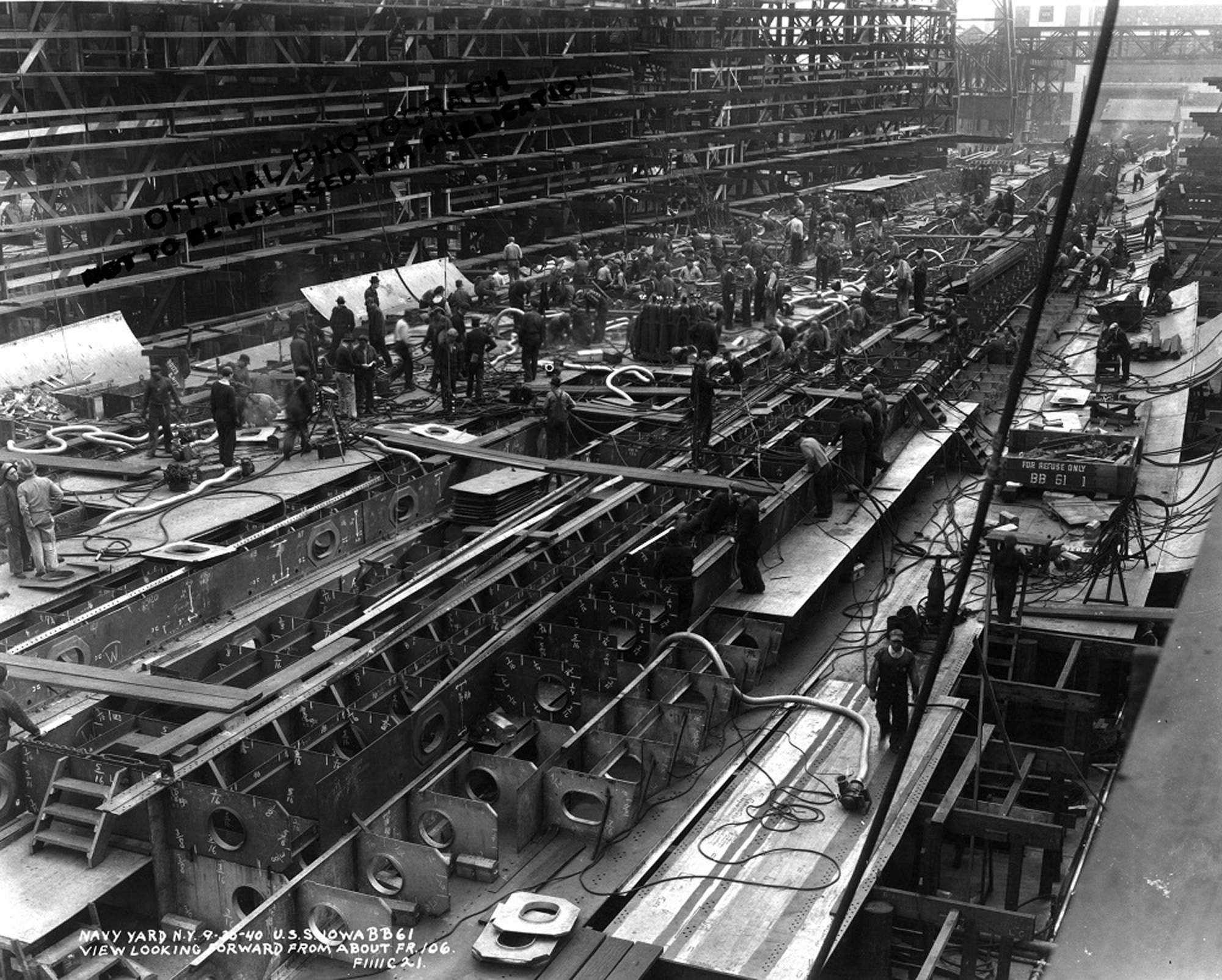

Iowa under construction

Figuring out how much a car costs is pretty straightforward. You look at the sticker price, or the price you paid for it. Major military hardware like tanks, planes and ships is different. It's produced in only limited quantities and involves a massive amount of research, development, and engineering before the first unit goes into service. Because of this, the companies that build it are rarely willing to do what auto makers do and take the risk of paying for the development themselves and recovering the cost from the units that they sell. What if they price it to recover the cost with 1,000 units and the customer suddenly decides to cut their buy in half? Now they're out a bunch of money, and the stockholders are unhappy. To avoid this problem, development is paid for by the customer separately from procurement of each item. Well, more or less. The actual answer varies with each particular system, accounting method, and time of the month. But in general, costs break down that way.

So why does this cause so much confusion? Well, it all has to do with what gets reported. Someone who is trying to make the case that some program is outrageously expensive and should be cancelled is going to lump together development and procurement, divide by the number of systems involved, and then publish the resulting number. But, particularly when we’re discussing the cost of a system about to enter production, that number can be very deceiving. To give a well-known example, the B-2 is generally reputed to have cost about $2 billion/plane in the early 90s. However, this is the total program cost divided by the 21 airframes. If we’d decided to buy 22 B-2s instead of the 21 we did buy, the extra plane would have cost only $700 million or so. Admittedly, the B-2 is a rather extreme case, and usually the share of R&D cost is less than the marginal procurement (flyaway) cost, but it’s illustrative of the power of this kind of framing.

F-35B landing on USS America

Of course, flyaway cost isn't fixed either. Military projects tend to have high overheads, because doing cutting-edge manufacturing is complex. This can mean that buying, say, 500 missiles a year instead of a thousand might drive the unit price up 50%, meaning that the total price in year 2 is about 75% of that of year one. There's also a considerable learning curve as the kinks are worked out in production. The per-unit cost, not including R&D, on the F-35A has fallen from somewhere in the neighborhood of $275 million for the original batch in 2008 to around $85 million for the FY2019 units. Some of this is due to volume growth (for a long time, the F-35C was as expensive as the more-complex F-35B due to low volume), but the rule of thumb for aircraft is that unit 2X will cost about 80% as much as unit X.

This is probably all making sense, but unfortunately we're not done, and it's just going to get more confusing. Another common pothole is government-furnished equipment, or GFE. This is stuff that is bought separately from the main contract, and not billed under the same line item. This can include anything from minor items up to engines, big guns, and electronics. In a few cases, these are procured at internal government facilities, but they're more often just bought under separate contracts, which can make figuring out true prices rather difficult. This is a particular problem on warships, to the point that I'm not sure of the true cost of the Iowa class.1 Sustainment costs can cause similar problems to financial analysis. Some of this is the everyday fuel, maintenance, and personnel, but a lot of it goes to making sure that the platform stays capable over several decades in the face of evolving threats. In a lot of cases, this can add up to more than the original build cost, and it's difficult to figure out how to assign it. Worse still, it's not unknown for critics to bundle sustainment in with R&D and basic procurement for the unit costs. This is perfectly reasonable when using it as a metric for analyzing different options to get the best bang for the buck (for instance, you might be able to pay more upfront to cut down on operating costs over time), but it's deceptive when presented as a current cost for a multi-decade program like the F-35, particularly when we are going to need some kind of fighter over that time anyway.

Type 45 HMS Daring

Finally, there's the downright bizarre, which usually means the British are involved. It's been said that the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) is excellent at creating situations where it's not even possible to tell if they made the right decision. A recent example is the Type 45 destroyer. Originally, 12 were planned, and the program was structured to make it so that no money would be saved by cutting units. (I have no idea how this was done, and most of me doesn't really want to find out.) Of course, after doing that, the buy was cut down to 6 ships anyway.

I've only scratched the surface of military pricing, but I hope I've been able to give a better understanding of why the numbers you see are definitely wrong in some way, and the ways in which these mistakes can lead to bad policy. Unlike consumer goods, military equipment involves substantial overheads in both R&D and production, making understanding true costs complicated. And there are sufficient degrees of freedom involved that motivated parties can easily come up with numbers to support their claims that are technically true but seriously misleading. This isn't limited to opponents of weapons systems, either, although it's somewhat harder to play the really big games to bring reported prices down.

1 Or the Burkes, which have their engines procured under a separate budget item from the rest of the ship. ⇑

Comments

"And then there are sustainment costs. Some of this is the everyday fuel, maintenance, and personnel, but a lot of it goes to making sure that the platform stays capable over several decades."

I wonder if this will become more common as semi commercial products move towards more service based models, rather than cash on the barrel at delivery. I know the airlines are doing that with their engines, essentially renting them from RR or GE for a fixed price per hour to cut down on maintenance uncertainty. For some stuff this doesn't seem practical, but for the P-8 or KC-46, I wonder if that's the future.

For a major war, it seems like having the military maintain organic MRO functions seems worthwhile (at least up to the depot level?), but under the current model maybe moving more of the maintenance to contractors or the original integrator would save money and reduce future uncertainty, or maybe it would just reduce accountability and increase costs.

My earlier comment was a little incomplete. What I was getting at is maybe we'll see more contacts where sustainment is bundled with procurement. So, instead of contacting for just X airframes delivered to Wright Patteraon, or Z LCS competed at Marinette, the DoD contacts for twenty five years and 50k hours of refueling airframe availability, or something like that.

That's an interesting idea. I'm aware of what's being done in that sphere on the commercial side, but I'm not sure it will translate well to military operations. One of the big problems with running the military by contract is that a military needs to have lots more slack in the support chain than a commercial operation can afford. Airlines are always flying their planes as hard as they can. The military flies their planes at maybe 10% of the rate of commercial, but they have to maintain the support structure for full-rate operations. Contractors aren't going to like that, and it's a lot harder to ship them off to the far side of the world. For the really heavy stuff, it may be contractors or civil servants doing the work, but I doubt it will go as far as it has on the commercial side.

Oh, yeah, sure, I really need a flat in Moscow...

Bugger off!

@Emilio: assuming that was directed at the spammers, they appear to have been stopped.