Britain decided to acquire nuclear weapons almost as soon as their existence became public, rightly seeing that they would be necessary to be seen as anything approaching a great power. Initially, the only possible deployment mechanism was the manned bomber, and the British developed three, collectively known as the V-bombers, in the early 50s to deliver their weapons to targets in the Soviet Union.1 But by the early 60s, this force was seen as increasingly inadequate and vulnerable thanks to developments in missile technology.

Vickers Valiant, one of the V-bombers

The V-bombers faced two separate problems. First, surface-to-air missiles had apparently rendered the high-altitude bomber obsolete, and while a shift to low level could preserve the viability of the deterrent in the short run, the future was seen as belonging to ballistic missiles. The British were working on a land-based missile known as Blue Streak that would replace the V-bombers, but it shared the second problem with the earlier force. Britain was simply too close to the Soviet Union, which meant that it would have only a few minutes warning of any attack. Bombers on ground alert wouldn't have enough time to get safely away, and Blue Streak would have to be on a hair trigger, opening the very real possibility of starting World War Three by mistake and going against all doctrine around nuclear weapons. Britain's geography posed another problem, in that the relatively small size of the country meant that any Soviet attack would do massive collateral damage, particularly if it was targeted at the hardened silos planned for Blue Streak. As a result, the missile was cancelled in 1960.

A B-52 carrying hypersonic weapons

The British had to choose between two alternative missiles, both of them American: the Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile and Polaris. Both had been under consideration for some time, and the initial decision was for Skybolt, which could be fitted to the existing V-bombers, giving them a thousand-mile standoff at a price presumed to be far lower than that of Polaris. It was also easier to get, as the US was trying to create a nuclear force for NATO, in an attempt to end the independent British and French deterrents, and giving the British unrestricted access to Polaris would undermine that. Skybolt was seen as merely an adjunct to the existing V-bombers, and the British were able to use the American desire for forward bases for Polaris as leverage to get the Skybolt sale approved in 1960, with Polaris agreed as a backup in case the program failed.2

An RAF Skybolt

This was a wise precaution. Skybolt was a tremendously ambitious program and testing, beginning in 1962, did not go smoothly. The Kennedy Administration had arrived the previous year, and the new Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, promised to subject all programs to "rational analysis".3 In practice, some of his cancellations were more about exerting power over the services, and Skybolt was one of the less regrettable casualties of his purge. However, this left the British in an awkward spot, made worse by the Kennedy Administration's rather strange beliefs about nuclear warfighting and consequent opposition to independent deterrents.4 Many wanted to deny them any replacement, forcing them to instead participate in the proposed Multi-Lateral Force, a NATO deterrent based around using Polaris from surface ships. These ships would be manned by personnel drawn from various nations and NATO governments would have some degree of control over the weapons. German involvement tended to make the rest of NATO nervous, and the plan was eventually scrapped.

The standoff was eventually resolved at a summit in Nassau just before Christmas 1962 between Kennedy and British Prime Minister Harold Macmillian. In the end, Macmillian essentially won, with the US agreeing to supply Britain with Polaris missiles, to be mated to a British-designed nuclear warhead. As a face-saving compromise, the submarines would officially be assigned to NATO, although the British could withdraw them in a "supreme crisis" for purely national ends. In practice, they would be British-manned and British-controlled, frustrating Kennedy's aim of ending the independent British deterrent.

John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillian at Nassau

This left the question of what sort of submarines would carry the missiles. The Admiralty considered several options besides the obvious 16-missile boat like the Americans used. Because the British Polaris force was going to be much smaller than its American counterpart, many wanted to make the submarines smaller, allowing them to use numbers to frustrate the enemy's ASW efforts. Others, wary of dedicating so much money to what were essentially single-purpose vessels, asked if it would be possible to build hybrid SSN/SSBNs, each carrying 8 missiles. Both of these plans failed, as an 8-missile submarine was only slightly cheaper than a 16-missile submarine to build and operate, and the idea of putting extremely valuable Polaris missiles on a submarine that would go around attacking things was dubious at best. But even once the decision for a proper 16-missile SSBN was made, there were still questions of how best to get them to sea quickly. One proposal was to build boats to American plans, scrapped because the components were dependent on the American industrial base and producing them in Britain would have required massive retooling. Another was to do what had been done for George Washington and slice Valiant, Britain's first domestic SSN and still under construction, in half on the ways and put a missile compartment in the middle. This was not done to avoid major disruptions to the SSN program, and they settled on cutting the plans for Valiant in half and putting in the missile compartment from the James Madison class,5 as well as an extension for the crew and machinery required to support it.

HMS Resolution on trials

The resulting Resolution class was significantly more sophisticated than the first American SSBNs, as Valiant was the first nuclear submarine to use rafting to silence its machinery. The British were ahead of the Americans in this critical area, and the new boats had a maximum quiet speed of 15.75 kts, with a top speed around 22 kts. For even quieter running, bypassing the noisy gearbox, an electric motor could turn the screw, either using the ship's turbines (7 kts) or the batteries (4.5 kts). One area where it surrendered an advantage to her American contemporaries was test depth, as Valiant was built of lower-strength steel, and redesigning for the high-strength steel would have destroyed the already-tight schedule.

A cutaway model of Resolution

The big question was how many boats to buy. The initial plan was for five boats, which would allow one to remain on station at all times, and raised the possibility of deploying one to the Pacific or Indian Ocean if needed to support British allies in times of crisis. China's recent detonation of its first nuclear weapon had made this a real possibility, but in 1964 a Labor government came to power under Harold Wilson, who was pretty far to the left and opposed to nuclear weapons. The first four boats had been ordered, but the fifth was suspended, and ultimately cancelled. There was also talk of cancelling one of the existing four, but this was shot down when it was pointed out that it would compromise the ability to keep at least one boat on station at all times, and wouldn't save all that much money, particularly given the overheads of the SSBN force.6 To keep availability high, the British used the same dual-crew system the Americans adopted, with crews designated Port and Starboard.

A Polaris A3 belonging to the Royal Air Force

When the initial agreement was signed, the British had planned to use the Polaris A2 missile, but they soon learned of the new Polaris A3, and the Americans proved willing to sell them that instead. However, the British chose not to participate in the next upgrade, the Poseidon missile with its MIRV warheads. Harold Wilson's government publicly rejected the option in 1967, and it was eventually closed off by the START treaty. But the rejection of Poseidon left the British with a problem. Soviet missile defenses were improving, and they were less and less sure that Polaris A3 would be adequate to hold Moscow at risk, the basic goal of the British deterrent. They could either reverse course and adopt Poseidon after all (the option favored by the RN) or try to improve the penetration capability of the Polaris A3. Steps in this direction had already been taken by the USN, which had developed a system known as Antelope which replaced one of the warheads on an A3 with a package of decoys. It had never been deployed, as the Americans had decided that the best way to deal with missile defenses was to throw more warheads, but the British adopted the concept as the basis for their improved missile, which they called first Super Antelope and then Chevaline, after a South African antelope species. Ultimately, it was selected because it was seen as cheaper and would produce jobs in Britain instead of in America.

The missile compartment of a Resolution class submarine

Development of Chevaline began in 1970, and continued for the next decade in extreme secrecy.7 The basic plan was fairly simple. One of the two warheads would be mounted about the Penetration Aid Carrier (PAC) along with a bevy of decoys, while the other would be ejected directly from the missile as in a normal Polaris A3. The PAC would move around, ejecting decoys as it went, before finally separating the second warhead. A total of 27 decoys were carried, which in theory should have raised the number of total targets enough that the Soviets couldn't shoot down all of the British warheads before some reached Moscow. The Soviets were prevented from solving the problem through brute force by the 1972 ABM treaty, which limited them to only 100 interceptors around Moscow and required them to leave other cities uncovered.

Chevaline's deployment sequence

None of this was as easy as it seemed for the British. The biggest problem with decoys is that they only work so long as they are indistinguishable from actual warheads.8 In space, this is relatively easy, as a balloon of the same shape as a warhead will generally look the same on radar. The problem comes when it hits the atmosphere, as the much lighter balloon will slow down more quickly, giving the defender an easy way to tell them apart. There were two ways to solve this. The first, chosen by Poseidon, was to make decoys the same size and weight as the actual RVs, and then fit them with nuclear warheads of their own. The second was to build more sophisticated decoys equipped with rocket motors to keep them from slowing down and hopefully preserve the illusion for longer. This was a tremendous technical challenge, and it was far from the only one faced by Chevaline. The PAC in particular was a headache for its engineers, with the cost of the program spiraling out of control. Initially estimated at £85 million in 1970, by the time it was revealed to Parliament in 1980, the cost had reached £1 billion, although with inflation taken into account, the actual overrun was approximately threefold. For much of the 70s, the program teetered on the edge of cancellation, as the British worried about cost, safety, and the credibility of their deterrent.

Chevaline

Chevaline finally entered service in 1982, and in theory gave the Polaris system another dozen or so years of service life, at which point the Resolutions would be reaching the end of their lives anyway. This was made more difficult by the age of the missiles, and even with the USN's remaining stockpile of spare parts, the British had to replace many components to keep the missiles safe and reliable. The biggest issue was the missile's motors, which had begun to degrade during storage, and replacements had to be ordered from the US at great expense. This managed to keep Polaris in service until Repulse was finally retired in 1996. It was replaced in the deterrent role by Trident, also bought from the US. We'll take a look at that program next time.

1 We've previously taken a look at some of the later exploits of these planes. ⇑

2 One other advantage of this was that it avoided a really nasty interservice fight over the deterrent, as relations between the RN and RAF were not particularly good in this era. Amusingly, at one point two complete Polaris boats were considered as the price of the base at Holy Loch, but this plan was never formally proposed. ⇑

3 Now is not the time or the place to go into detail about McNamara's tenure at the DoD, but what happened was neither rational nor actual analysis. ⇑

4 The short version is that they believed the world constantly teetered on the brink of nuclear war, and that situations had to be carefully managed to avoid Armageddon. Independent deterrents (Britain and France) were wild cards that risked destabilizing the whole thing. None of this was really true, and in their obsession with signalling and avoiding nuclear war they forgot about actually winning, most notably in Vietnam. ⇑

5 Some British sources say George Washington class, but this is unlikely for reasons of timing, and because the ships were reportedly able to support Poseidon. ⇑

6 DK Brown suggests that these overheads were driven up by the small force, suggesting that cancelling the fifth boat may not have saved that much in the long run, either. ⇑

7 At least some of this was because the British anti-nuclear movement was always much stronger than that in the US. There was a serious proposal at the start of Harold Wilson's second government to get rid of Polaris and turn the SSBNs into SSNs. Unlike Soviet and American SSBN to SSN conversions, this would involve taking out the missile compartment entirely. The biggest problem would be aligning the two halves before they were reattached. ⇑

8 I should probably mention that I am very unsure of the actual effectiveness of decoys against ABM systems. There are a lot of people who act like they'll be very effective, but there are also people who act like they won't, and it's sometimes the same people. I suspect that modern sensors are quite good at telling them apart, but that's going to rely on throwing lots of computer power at the problem, which means that Chevaline might have been effective at the time. ⇑

Comments

I can't wait for your McNamara post

You'll have to wait a while on that one. That's one where there's a fair bit of controversy, so if I'm to wade in, I'll need a lot of sourcing, and that takes time and effort.

In retaliation for the “The MLF Lullaby”, I offer the following cuica solo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhOUnWv2X8A

McNamara still has supporters? I read his auto-biography. Even McNamara doesn't support McNamara's decisions.

It's not so much that he has supporters as that a lot of the claims are more outrageous and harder to source. Also, his mistakes also make Kennedy and Johnson look bad, and they do have supporters.

You make a very good point about the Kennedy angle. I hadn't considered it.

bean:

Weren't the British working on it before they were public knowledge?

bean:

The US use Blue and Gold The French use Red and Blue

Why can't the British just call them Red and Green?

bean:

You call those decoys?

bean:

In fairness it probably wasn't obvious he'd screw up so badly when JFK appointed him.

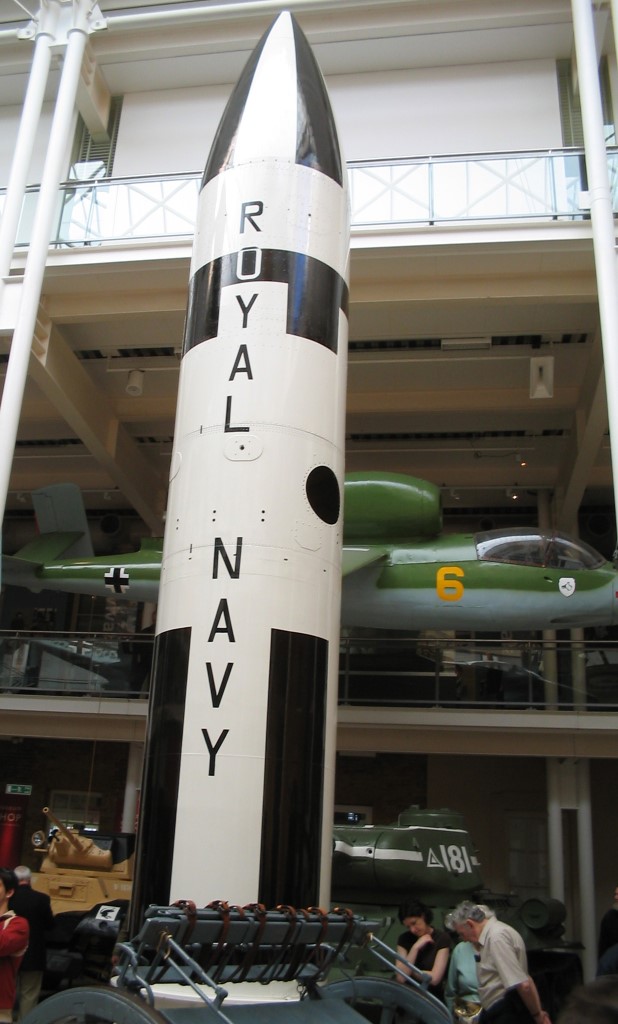

How did the RAF come to have Polaris Missiles? And why did they mark them 'ROYAL NAVY'? That looks like a photo from the Imperial War Museum.

Anonymous's point about British development of nuclear weapons is a good one. They start off investigating them before the Americans, then hand the research over. What happened then? Did they just stop, trusting that their allies were dealing with it, and they had other things to focus on during the war? Then suddenly it's over, the US have the bomb, and aren't keen to share?

The US anti-ballistic missile Sprint had incredible performance to enable it to hit the reentry bodies after the decoys had slowed down. If the Soviets didn't have a comparable missile, but could shoot down warheads before they began (or at the beginning of) their terminal phase, the decoys might have been the better choice, especially if all your missiles are to be used against the one target in the country that has ABM defences. It seems silly not to have just gone with Antelope though.

@Anonymous

There was stuff like the MAUD committee, but the whole thing got handed over to the US, and Britain's contribution was mostly just to send scientists and help supply some materials, IIRC. There was a separate decision to actually procure the weapons made in 1945.

That was essentially the framing used by the original Poseidon planners. "If the best decoy is a nuclear warhead, then we'll just make more of those."

Nor was it so obvious that JFK would screw up so badly when the American people appointed him. (No, not just by appointing McNamara. Longer version of that is in Norman Friedman's The Fifty Year War.)

@Alexander

It was a joke.

Your proposed summary of British nuclear weapons development is more or less accurate. We shared a bunch with the British during the war, but immediately postwar, Congress had one of its isolationist fits and cut that off.

As for ABM, the Soviets didn't really have anything like Sprint, which did drive some of the decisions made for Chevaline.

No argument here. Well, I'd say it was silly not to go with Poseidon when they were offered it, but that's a different matter.

Tube Alloys was the codename of the British program to investigate the feasibility of a nuclear weapon. An early war paper by the scientists Peieris and Frisch led to the formation of the MAUD Committee.

The Tube Alloys program was folded into the Manhattan Project under the Quebec Agreement. This cooperation ran until around 1946 when the British re-launched their own nuclear weapons efforts.

By the way, one of the scientists sent by the British was one Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs...someone who would have been best kept out of things.

@neal

To be fair, I'm not sure that there was anyone in the UK who went to Oxford or Cambridge that wasn't a communist spy...

If Poseidon has 10+ warheads, and Polaris with Chevaline 2 and 27 decoys, Poseidon sounds like the better option in most cases, particularly if it comes over a decade earlier. There would still have been the option to replace a warhead or two with decoys and get the best of both, perhaps sharing development costs with the Americans. Perhaps it was another one of those decisions where the primary goal was to channel money to UK industry, and actual procurement was a lesser priority.

The way the US swings from isolationism to interventionism is hard to understand, and probably the result of different groups gaining the upper hand in an internal debate at different times. From the outside though, you have a country that has just fought in the biggest war in history, and is going to station troops in Europe to the present day, but somehow the relationship with its strongest potential ally in Europe isn't worth maintaining.

@cassander

"To be fair, I’m not sure that there was anyone in the UK who went to Oxford or Cambridge that wasn’t a communist spy..."

You do have a point there. At one time it seemed as if Oxbridge had an assembly line set up.

Obviously Fuchs came in from a bit of a different angle, but he certainly had no trouble finding waters in which to swim.

For those not familiar with the story: Klaus Fuchs was a German physicist who came to the UK as a refugee, gained British citizenship after the outbreak of WWII, worked on the Manhattan project ... and spied for the Soviet Union, supplying information that helped the Soviet nuclear-weapons program to proceed as quickly as it did.

Did you ever get to read ThinPinstripedLine's take on the happenings at Whitehall during the Chevaline procurement process?

https://thinpinstripedline.blogspot.com/2021/11/making-mess-of-moscow-criterion-british.html?m=1

It's a fascinating story.

@Alexander: If we simplistically assume that Moscow is protected by 100 perfect ABMs, matched against Chevaline's 27 perfect decoys, then it takes 4 Polaris-Chevaline missiles to put an expected 200 kilotons onto the Kremlin, whereas 10 Poseidons will have no effect. The eleventh Poseidon delivers 10 x 50 kT against Moscow, but it's not unreasonable to assume that most of the deterrence value comes from the first thermonuclear airburst over the Kremlin.

If that's not the case, a dozen more Polaris-Chevalines give 8.2 equivalent megatons over twelve target areas in Russia, whereas the five remaining Poseidon missiles from the UK's hypothetical at-sea Poseidon boat would only give 6.7 equivalent megatons over five target areas.

And it's not clear that replacing a couple of Poseidon warheads with decoys buys you that much, because the Poseidon bus doesn't have the performance to deliver a broad and confusing decoy pattern. Remember, at this point we're talking about ABMs with more thermonuclear kaboom than most ICBMs; just tossing your decoys over the side doesn't accomplish much.

Polaris/Chevaline looks pretty good for the mission of, A: make absolutely certain that Britain's one at-sea deterrence boat can vaporize the Kremlin, and B: retain as much flexibility as possible for doing other stuff once A has been guaranteed.

@Chris

I had missed that, but it was very interesting, and I'll definitely have to link it from here. Thanks.

@John

OK, but what happens if we assume that neither the decoys nor the ABMs are perfect? I know that not all of the Chevaline decoys were the same. Details are obviously classified, but the extremely sophisticated ones were pretty heavy, and only a few were carried. A significant fraction were only for early phase work, and were quickly stripped off by the atmosphere. Drops in both ABM effectiveness and decoy effectiveness both work in favor of Poseidon, and both are likely to be less than 100% in the real world.

If going from 3 ReBs to two allows Polaris to scatter decoys over a 150 mile 'Threat-tube', why couldn't a reduction in the number of warheads allow Poseidon to do the same? Would you pretty much have to reduce the number of bombs all the way down to two to allow it?

It's hard to work out the importance of actual performance for a weapon intended entirely as a deterrent. To some extent allowing uncertainty over the effectiveness of the decoys could be acceptable, if the Soviets are assumed to be cautious. The ABMs are more of an issue, as NATO presumably knows less about them than their designers, and if the Soviets did believe (accurately or not) that they work perfectly, you need to be able to credibility threaten to overwhelm them with too many targets, even with just one boat's worth of missiles.

I don't suppose we now know what the Kremlin was thinking about the threat at the time?

Alexander:

All weapons are primarily deterrents with winning a fight being a failure mode (because if they scared the enemy properly they'd give in without a fight) and there isn't a weapon that isn't intended to be able to win even if it fails as a deterrent.

Fair point. Is there a sense in which nuclear weapons are different, as they are so rarely (practically never) used, or would you say no more than, say, F-14s were never really tested against a Soviet Naval Aviation raid, instead successfully (contributing to) deterring it?

I would say that nuclear weapons are very different in that they are explicitly designed for their effects on deterrence, which nothing else is. I've never seen anything else analyzed through the lens of "will this be seen to work by our enemies". Everything else just uses "will this work". Sure, we hope our net military strength deters conflicts, but no conventional system is as important as a nuclear system, and there's a good chance that any conventional system will have to be used. There's a lot of this in the Thin Pinstripped Line post Chris linked.

Well Posideon was a nuclear deterrent against the Americans not using a nuclear deterrant to deter a soviet invasion of Europe.

@Alexander: It's not the elimination of one warhead that gives Chevaline its edge, but the addition of the highly capable Penetration Aid Carrier. You can incorporate that sort of capability into a MIRV bus if you want, but Poseidon didn't really try - it optimized for largest number of warheads possible, dispersed just broadly enough to avoid easy multiple kills by a thermonuclear ABM (and to target multiple aimpoints in the same large urban area or equivalent).

Roughly speaking, with Poseidon you can deploy ten things widely enough that an ABM can only kill one of them, and it doesn't much matter what the things weigh because the bus weighs quite a bit on its own. So they might as well be warheads. With Chevaline, you get broader distribution so long as 27/28ths of the things are lightweight, because you're ditching most of the total mass before you start the fancy maneuvering.

And, yes, the math gets much more complicated if neither the ABMs nor the decoys are perfect. But from a deterrence perspective, the British are going to conservatively assume that Soviet ABMs are very effective and the Soviets are going to similarly assume that British decoys are highly effective.

bean:

They also run full up tests on everything else, have any currently in service nuclear weapons ever had a full up test?

@John What if one of the ten things deployed by the Poseidon bus was Chevaline (or equivalent)? You replace two of the warheads with a Chevaline style PAC with one warhead and a bunch of decoys. The PAC creates the threat tube around the remaining 8 warheads, which are deployed as normal by the bus. Would that work? Or would the Soviet radar operators just see the first eight objects appear, mark them as priority targets, and only the one warhead on the PAC gets any protection from the decoys? Or perhaps a separate bus and PAC is a bad way of going about it. As you said "You can incorporate that sort of capability into a MIRV bus if you want, but Poseidon didn’t really try". Rather than mucking around with both, you would be better off redesigning the bus altogether? Or, I suppose, giving up on decoys as more trouble than they're worth (presumably the actual US decision) Ü

Having read the The Thin Pinstriped Line post, my understanding is that the British ambivalence towards nuclear weapons at the time lead them to commit to not aquiring more. Without questioning the wisdom of that decision, once you have made that choice, it pretty much rules out Poseidon as an option. From John's point about making conservative assumptions around nuclear war, and 'Seven days to the river Rhine' I think that the British could reasonably say that Polaris was adequate from a deterrence perspective, even if it would have been inferior in an actual nuclear war.

With regard to Anonymous's point about how conventional weapons are also designed to deter, and nuclear weapons deter because of their utility in a war, I was reminded by Cassandar's comments about how Taiwan/RoC should focus on deterring invasion rather than mirroring US decisions. I definitely see a difference in degree to which deterrence is the priority with nuclear weapons - that was what lead me to make the comment that Anonymous corrected. Now though, I also see strong parallels between NATO strategy during the cold war (deter the communists from invading by aquiring weapons that make an invasion too costly) and Cassandar's proposed strategy for Taiwan (essentially the same).

Was humming the Lehrer song before noticing the link. Still absolute gold all these decades later.

Could the UK nuclear establishment have been against Poseidon because they couldn't design a small enough primary to have "their own" version of the warheads? It looks like they had to directly copy Trident's W-76 from US plans, which might just be a polite way of saying they bought and assembled a kit.