While the Americans were the first ever to operate manned lighter-than-air devices from ships, they abandoned the idea after the end of the Civil War, and didn't return to the LTA arena until quite late. Their first naval blimp, DN-1, was ordered in 1915 and took two years to build. It's first flight failed completely, with the craft sinking into the water, and it was only after extensive work to lighten it that it was able to get into the air. Even then, it was less than successful, and it was quietly retired after the Navy accepted delivery.

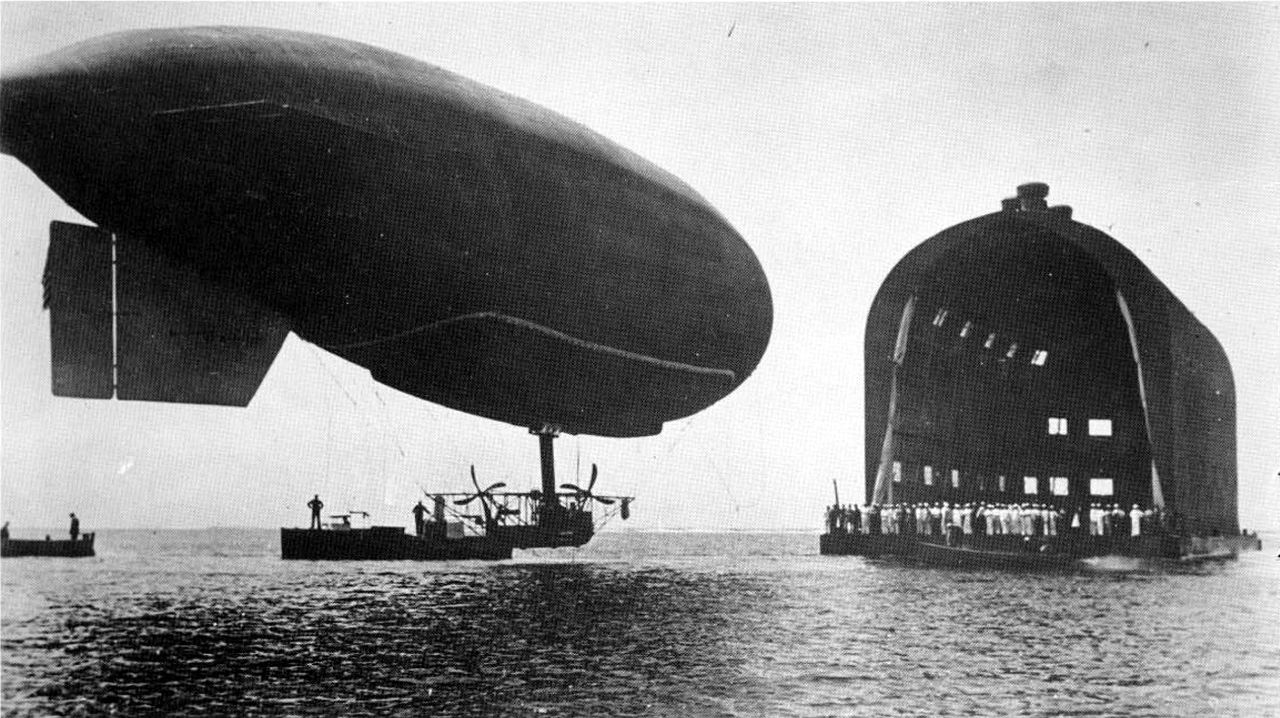

DN-1 is maneuvered into its floating hangar

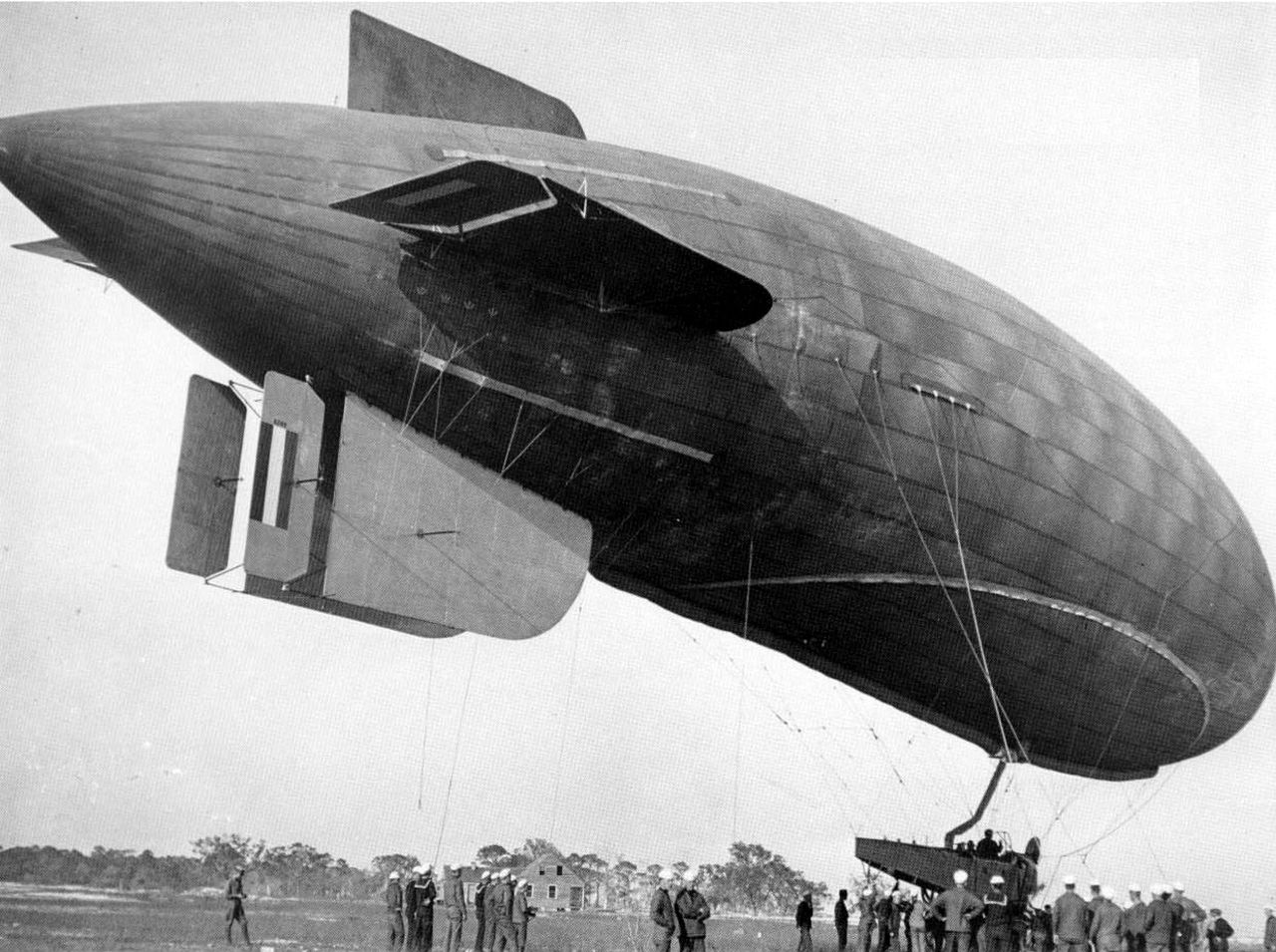

However, another class was already on order, and the so-called B-class, very similar to the British SS class, proved quite successful. 9 of the 16 envelopes were built by Goodyear, who would remain at the forefront of lighter-than-air aviation in America to the present. The B-class patrolled the American coast and gave valuable service as trainers for the burgeoning American naval airship arm. Kite balloons were also developed in the US, with trials on the battleships Oklahoma and Nevada souring the US on the concept of using them with the fleet. Most likely, the British method of simply servicing the balloons ashore was seen as unworkable for the USN, who expected to fight much further from its bases. The kite balloons and early blimps gave good service after the outbreak of war, countering the German U-boat offensive in the western Atlantic.

A kite balloon flies over an American battleship

When the US entered the war, the underdeveloped state of its aviation industry meant that American aviation units sent to Europe were equipped with British and French aircraft. The airship force was no exception, and American personnel were dispatched to both countries to participate in the ASW campaign. A total of six French blimps were used to patrol the Bay of Biscay from early 1918 until a month after the Armistice, when a pair escorted President Wilson's arrival in Europe. The US also purchased several British blimps, although only a few patrols were flown. The USN focused instead on kite balloons, with a number of patrols operated out of Berehaven. US battleships operating with the Grand Fleet also made use of British kite balloons, an experience that didn't leave the Americans with positive feelings towards the type.

AT-13, a French Astra-Torres airship, in USN service

The USN wasn't content to just use foreign airships, and in early 1918, ordered 30 of the new C class blimps, which had more lift for a larger payload of depth charges, two engines, and better endurance. Only a few were completed before the Armistice, and the buy was eventually cut to 10. The C class were responsible for a number of firsts for American airships, including a number of endurance records and the first transcontinental flight by an airship. A plan was made to fly C-5 across the Atlantic for another first, but after a test flight from Long Island to the eastern tip of Newfoundland, it was lost when a gust ripped it from the hands of the ground crew and blown out to sea, fortunately with nobody onboard. In 1921, C-7 achieved another first, becoming the first airship ever inflated with a new lifting gas, helium.

A B-class blimp

Up until this point, hydrogen had been the lifting gas of choice for all airships, and while it was relatively easy to manufacture by a process involving iron and steam, it had one major drawback. It was extremely flammable, and accidental fires destroyed a number of airships. Helium, which is not flammable, was a theoretical alternative, but it was far too expensive to use in 1917. Only three flasks existed, in the labs of the University of Kansas, with a value of $25,000 per cubic foot in 1917 dollars.1 They were in Kansas because it had recently been discovered that the natural gas fields under the Great Plains contained a significant amount of helium, and when war broke out, the USN embarked on a crash program to produce and purify helium for use as a lifting gas. Three plants were set up, and the Armistice caught 750 cylinders of helium on the New Orleans docks. This was only sufficient for a single inflation, but the program continued, and after the mid-20s, all US airships have used helium as a lifting gas. Its scarcity led to the establishment of the National Helium Reserve in 1925, with the explicit mission of ensuring that there was enough of the gas for the military's airships. Because it was an important strategic resource, export of the gas to other countries was banned, ultimately leading to the Hindenburg tragedy.

C-7, the first airship inflated with helium

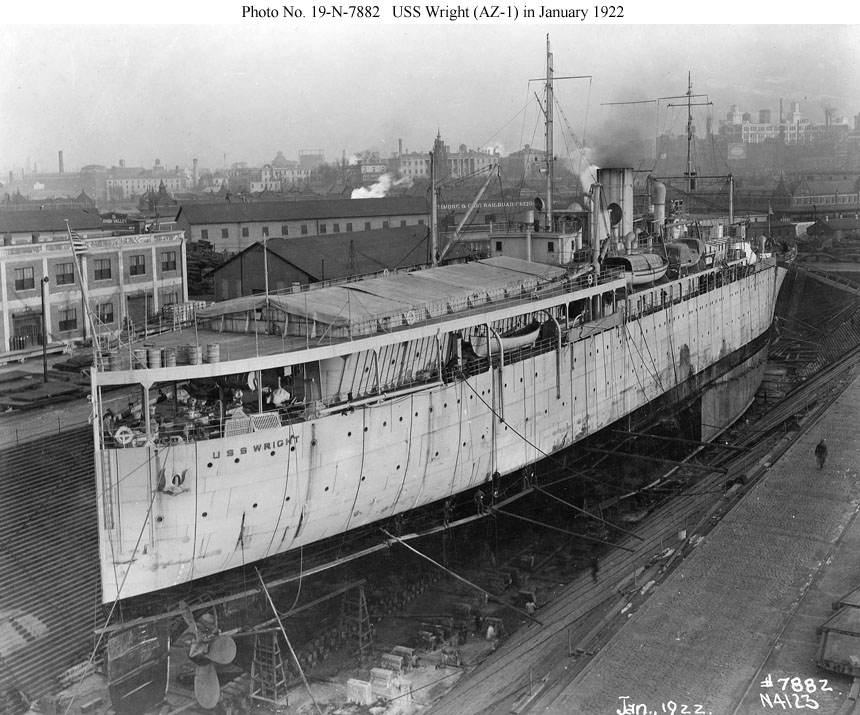

WWI was definitely the golden age of military lighter-than-air aviation. Postwar, most non-rigid airship programs petered out, with the USN surrendering the mission to the US Army, which had been given primary responsibility for the type in the ongoing interservice flap about aviation. In the UK, the new RAF was turning its back on naval missions in favor of a focus on using air power alone to win wars. The manned kite balloon was another casualty of the end of the war. Ship-based planes were considered more effective at gunfire spotting, while ASW was not on the minds of naval officers and developments in radio reduced the advantage of a wired telephone connection. The USN's sole ship dedicated to kite balloons, USS Wright, carried her balloons for only seven months before being converted to a seaplane tender. Unmanned kite balloons did reappear during WWII in the form of barrage balloons, which trailed heavy steel cables intended to snag low-flying aircraft. While few aircraft were actually destroyed this way, barrage balloons proved reasonably successful at forcing up attacking aircraft to altitudes where it was harder for them to hit their targets and easier for AA guns to shoot them down.2 These were most famously deployed to protect London during the Blitz, but were also used extensively by amphibious forces in the European theater.

USS Wright, showing her balloon well aft

But while the kite balloon disappeared and the naval blimp went into eclipse, one part of the lighter-than-air sector remained strong. Several navies maintained their interest in rigid airships, as they offered the potential for more effective scouting in an era of very limited budgets. We'll take a look at these efforts next time.

1 This is over half a million dollars per cubic foot in 2020 dollars. ⇑

2 An interesting footnote to the barrage balloon story is Operation Outward, which deployed crude hydrogen balloons trailing electrical cables to disrupt the German power grid, apparently quite successfully. ⇑

Comments

Never heard of operation outward before.

It's so interesting that I'm confused as to why I haven't heard of it.

Because it was operated by women?

I hadn't heard of it before I did some reading on kite balloons for this post. Not sure why it hasn't gotten more attention, because it seems tailor-made for the sort of "weird weapons of WWII" lists you see circulating. It may have been too successful for that, actually.

"Balloons could also carry incendiaries. Large areas of pine forest and heathland in Germany made the countryside vulnerable to random incendiary attack and it was hoped that the Germans would be forced to assign large numbers of people to the task of fire watching, possibly diverting them from more productive war-work. "

This is an idea I hadn't expected to see expressed in WWII in particular, that by forcing an enemy to honor a threat, the resources expended are not available on the front lines. I thought that was a later concept. (Though this is a generalization of the "fleet in being" concept, I suppose)

It's especially weird that this is so obscure given that the Japanese fire balloons are much better known. You'd expect that every article on the Japanese project would finish with a pointer to the much larger and more successful British example.

@Ian, I would have thought that so much of the "partisans" and "resistance" support in places from Russia to France were based on the same theory. They weren't able to actually do huge amounts of damage, but the resources needed to suppress them were resources not on the front line.

Ah, but you see, the British didn't kill any Americans with their effort (probably), so why would anybody care?

Sarcasm aside, I think the fact that it was the only enemy thing that killed people in CONUS is why the Japanese effort is so well-known. That aside, it's one of a thousand weird schemes that didn't really work.

Helium has twice the molecular weight of hydrogen if I'm not mistaken. So why didn't helium airships require twice the airbag volume?

Or perhaps they did - one-and-a-quarter times the linear dimensions might not be all that noticeable to the ignorant & unobservant, such as me.

@AlanL: The important thing for lifting power is the difference in density between the gas in the airbag and the atmosphere. It's easier to see the principle with buoyancy of stuff in water, where the lifting power is the weight of water displaced, minus the weight of the ship as a whole.

Average molecular weight of air is 29, which gives hydrogen a lifting power of 27 (29 - 2) and helium a lifting power of 25 (29 - 4). That's basically a 10% difference in volume needed for the same weight supported.

To add to what David said, helium airships did have a slight performance deficit to hydrogen for a given size. This was a problem for Shenendoah, which was designed for hydrogen, and then switched to helium. It's not hard to compensate for in design, but it is a potential issue.

I don't know how effective the incendiary component of Outward was, but I'm inclined to be sceptical based on the damp squib that was Operation Razzle.

Yes, let's have all our night bombers carry hundreds of little bits of phosphorus wrapped in damp cotton wool and sandwiched between sheets of celluloid, and chuck them out when flying over forests or cornfields on the way to their targets.

Leaving aside the awkwardness caused when "razzles" decided to ignite while still in the aircraft, and the stores-separation problems when they found their way back in after being dropped... it turned out that it's harder than we thought to burn down the Black Forest.

On the other hand, it did have one unforeseen effect. When a load of razzles got dropped by mistake on Bremen, the citizens mistook them for propaganda leaflets and, knowing the eyes of the Gestapo were everywhere, stealthily slipped them into their trouser pockets to take home and read. The results must have been embarrassing.

(Sadly, the only source I have for the Bremen story is Gibson's Enemy Coast Ahead, so it's probably apocryphal.)

@Ian, I think "forcing an enemy to hono[u]r a threat" was half the justification for the RAF's Area Bombing offensive. Keeps all those 88s away from the Eastern Front, don'cha know.

ec429:

Did it even do anything other than that?

"Did it even do anything other than that?"

Isn't that enough? It kept A LOT of guns (and associated resources - ammunition, crews, etc.) from going to the front, in whichever direction.

But yes, there was more. It also kept a lot of fighters (& etc.) from going to the front, in whichever direction. It also forced the Germans to spend scarce resources participating in an expensive technological race. And it also did put some pressure on German war production, though not as much as its architects had hoped for.

Going from vague, probably wrong, memory there was some ridiculous number like a million men devoted to air defence in Germany. That's including all the airforce, all the anti-aircraft gunners, radar operators etc.

Plus, an even more vague memory, some significant fraction of all German artillery. 1/3 or something? It was all pointing up in the sky and not pounding Russian tank positions.

Here we go https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defenceofthe_Reich

1.1 million men in ground based personnel alone.

Don't forget all the effort by the Germans to camouflage, harden and decentralize their industrial base. A factory built to produce jets or V-2s that has to built under a mountain is significantly harder to erect and service than one built on a plain.

For all you tank fans, don't forget that 95% of the Henschel plant assigned to build Tiger IIs was obliterated, with the corresponding loss of 650 Tiger II tanks in various stages of completion, which was substantially more than the number of Tiger IIs that were actually put into service.

@Chris Bradshaw,

Though a cynic might argue that the addition of 650 Tiger IIs would mostly serve to use up the last scraps of German fuel even faster.

Another part of my head canon that the untold story of WWII is how German engineers undertook a decade long deliberate campaign to sabotage the war effort by throwing away all the resources on impracticable, fantasy projects that would never be as militarily effective as just increased production of much more basic tech.

The Germans realized by mid-war that even if 100% of their resources were devoted to boring but mature systems like STuGs, Kar-98 rifles, and Bf-109 fighters, they would still be vastly outproduced by the combined industrial bases of the US, USSR, and British Empire. They had to strive for a high-variance strategy and pursue qualitative overmatch at all costs to have a chance. Fortunately, they were never able to achieve that desired level of performance due to the inherent difficulties of trying to jump a generation of technology in only a few years.