In the aftermath of WWI, navies worldwide looked to the rigid airship to augment the light cruisers traditionally used for scouting. Despite the failures of the German airship force in the North Sea, the allure of a fast, long-range scout with a great view was strong, particularly in the United States. Some of this was the American fascination with new technology, but it probably owed much to the chronic USN shortage of light cruisers due to a decade of Congressional preference for buying battleships and destroyers.

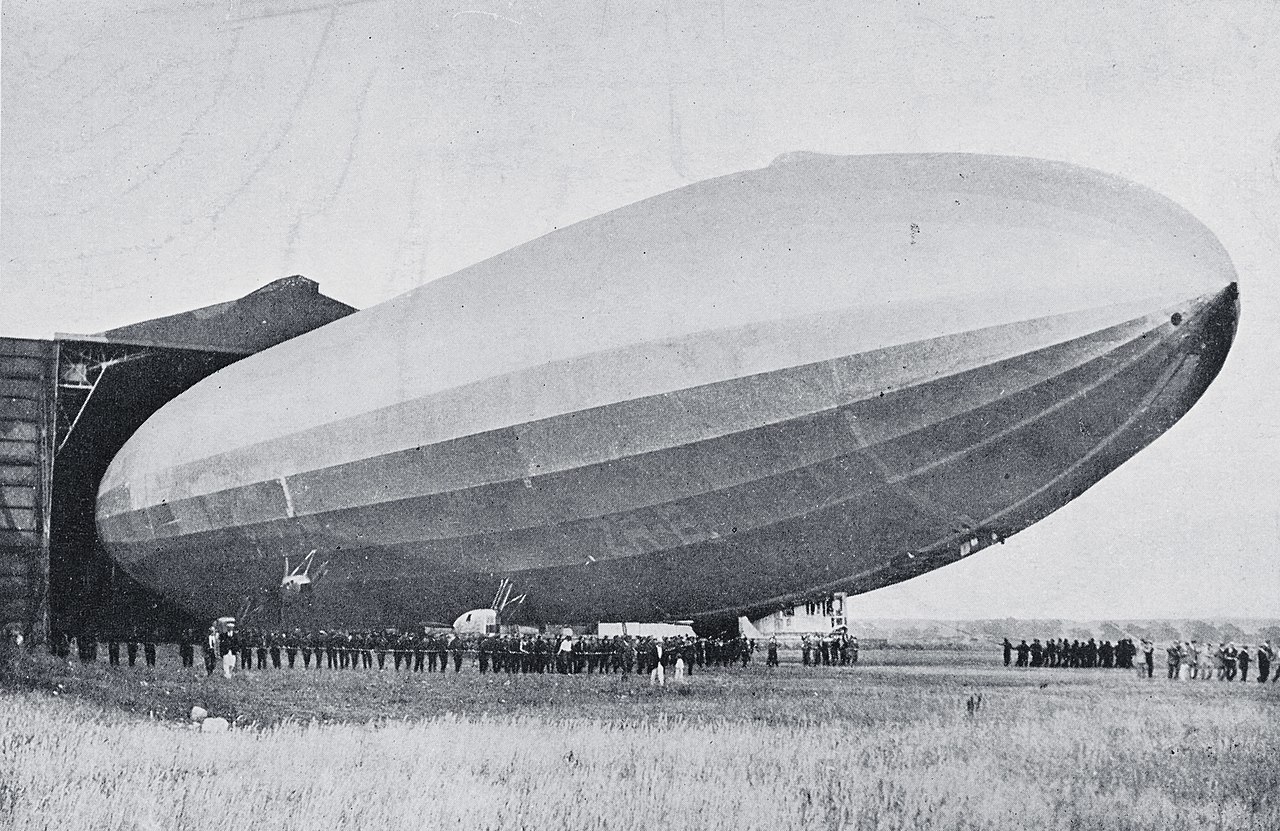

R34 lands on Long Island

Initially, the plan was to build the force around a pair of German Zeppelins that the US was slated to receive as war reparations, with later units built in the US. However, the German crews, in the finest traditions of their navy, chose instead to sabotage them. To replace those as its nucleus, the USN turned to the British. The Air Ministry had decided to shut down the British military airship program due to the financial crisis facing Britain and repurpose the existing airships for commercial use. Despite the successes of the commercial program, most notably the first round-trip crossing of the Atlantic by air in July 1919 with R34, the existing airships under construction were to be scrapped, at least until the USN agreed to buy R38 from them.

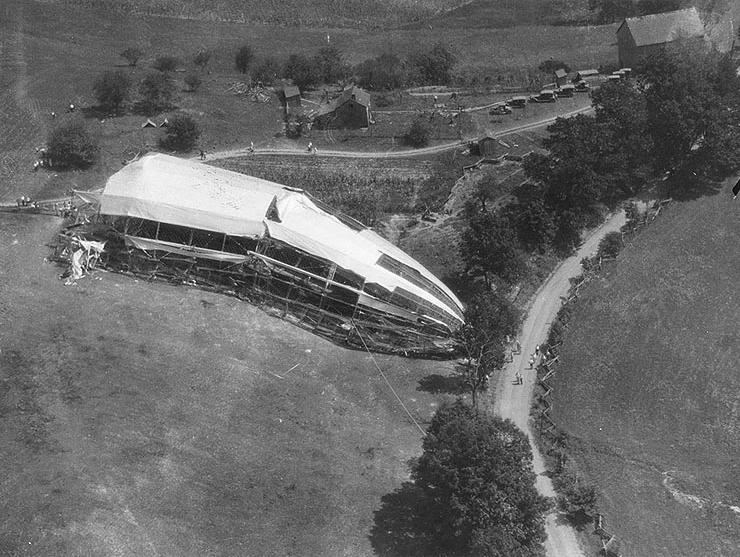

R38 is moved out of her hangar

R38 had been designed by the Admiralty as the ultimate patrol airship for use over the North Sea, with six days of endurance and over a ton of bombs. Construction hadn't started until early 1919, and she was finally completed in 1921. The plan was to run trials under a British crew with Americans working alongside them to learn how to operate the ship that the USN dubbed ZR-2.1 The Americans would then fly the ship themselves for a while before undertaking the transatlantic crossing.

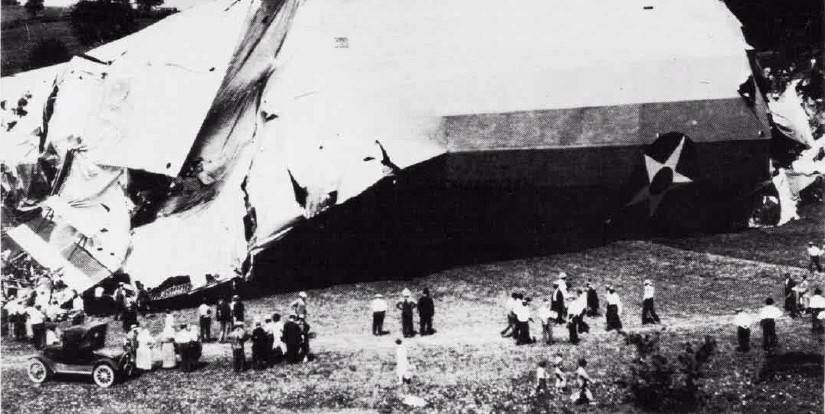

Rescuers move through the wreckage of R38

Unfortunately, the basic design, copied from a crashed Zeppelin, proved to be weak, with several failures taking place on early trials. These warning signs were ignored, and on August 24th, 1921, R38 broke up while maneuvering at low altitude. She was near the city of Hull, and hundreds saw the airship crack in half before the wreckage ignited as it plunged into the Humber. 44 of the 49 aboard died with R38, the cream of both the American and British airship establishments. The RN and RAF were immediately at loggerheads, with both groups blaming the other for the disaster. The Americans, meanwhile, were able to salvage something from the disaster. Germany remained liable for the Zeppelins that had been sabotaged in 1919, and had been offered the option of either paying in gold or building replacements for civil use. The Americans favored the later option, but the other Allied powers, most notably the British, objected, wanting the Zeppelin company dead. The stalemate lasted until the R38 disaster, when British embarrassment and American determination to get the best possible airship finally cleared the way for the airship that became ZR-3.

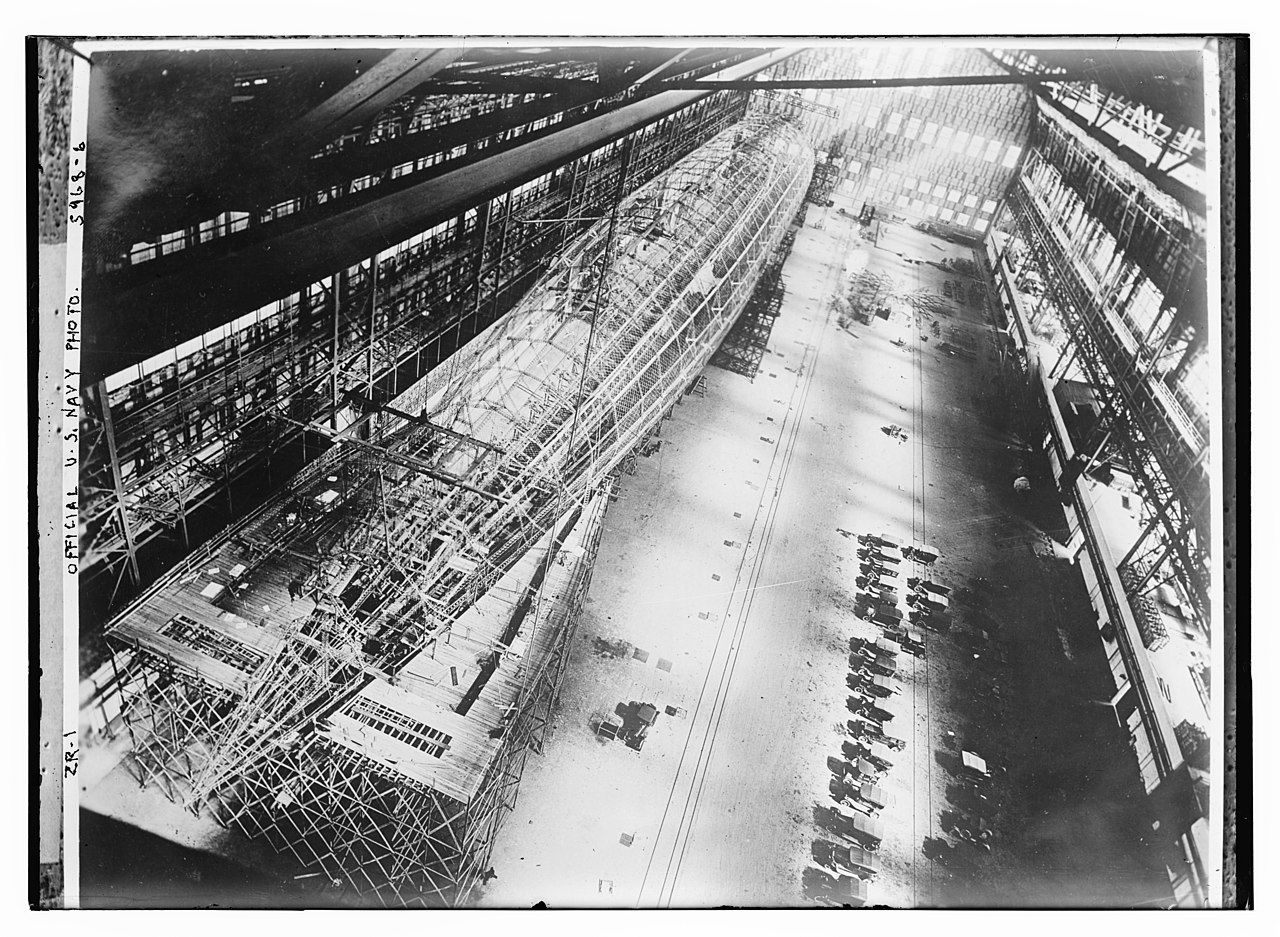

ZR-1 under construction

But the disaster did mean that the USN's rigid airship force would begin with a domestic design, ZR-1. Work had begun in 1919, but it took two years for the plans to be finalized, and the result was far from the state of the art in Europe, despite collaboration with the Zeppelin company. However, she did break new ground, particularly in the use of aluminum alloys in aircraft construction, experience later applied to heavier-than-air aircraft. ZR-1 was to be assembled at the Navy's new airship base, NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, a process which took most of 1922 and 1923. Upon completion it was commissioned as USS Shenandoah, just as if it were a ship. Besides being the first American rigid airship, Shenandoah was also the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium, as a result of safety concerns stemming from the R38 disaster and the loss of the Army semi-rigid airship Roma in 1922. Unfortunately, helium only provided 92% of the lift of hydrogen, which Shenandoah had been designed to use, and the decreased lift meant that fuel would have to be reduced, cutting range by 40%. Also, inflating Shenandoah took the vast majority of the world's helium supply at the time, and careful measures had to be taken to preserve the strategic gas.

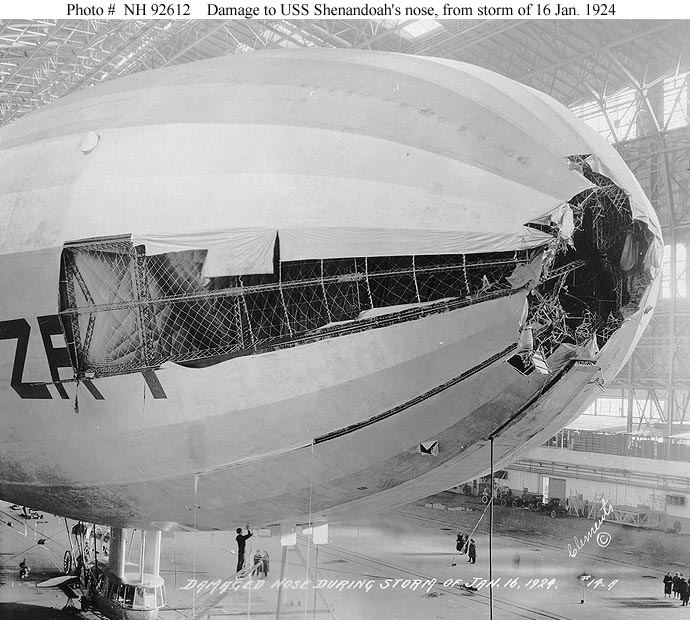

Shenandoah in hangar

Despite these problems, Shenandoah was an immediate success, captivating the public's imagination. William Moffett, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, was quick to appreciate the PR value of the airship, and Shenandoah spent much of her time on the county fair circuit,2 instead of doing development work with the fleet. To gain further publicity, as well as some operational experience, Moffett planned to send the airship to explore the arctic. This would involve supporting it at long distance from its base, made possible through the use of a new technology, the mooring mast. This was a tall tower that the airship's nose would be attached to, allowing it to weathervane as the wind shifted. In January 1924, Shenandoah was at the mast at Lakehurst when a storm blew up. It was decided to leave her there to gain experience in bad weather, with a partial crew aboard. Unfortunately, the storm was more violent than anticipated, and the airship was torn loose, leaving a section of her nose behind.

Damage to the noise of Shenandoah after the storm

The airship was now in serious peril. Not only was she loose in a storm with 60 mph winds, but the two forward gas cells had been ripped, and Shenandoah's nose barely cleared the trees on the edge of the field. Ballast was dropped and the engines started, and the crew eventually gained the upper hand, turning the airship's nose into the storm over Newark. The radio had been disassembled, and the radiomen worked frantically to reassemble it, finally making contact with the ground. As the storm abated, the crew were able to nurse the crippled airship home, arriving back at Lakehurst nine hours after breaking loose. The drama captivated the nation, and the crew were hailed as heroes. An overhaul had been planned before the Arctic trip, and it was now combined with the necessary repairs.3 Modifications were also made to the mooring mast hardware to ensure that the coupling would let go cleanly before it did any damage to the airship. In the aftermath of the accident, the command structure was also reshuffled, and Shenandoah was placed under the command of Zachary Lansdowne, probably the most experienced airship officer in the Navy.

Shenandoah docks with Patoka

In the summer of 1924, Lansdowne took Shenandoah out to operate with the fleet for the first time, with the highlight being the first use of the airship tender Patoka. Patoka had been built as an oiler, and then modified with a mooring mast (making her the tallest ship in the Navy at 177' above the waterline), helium and fuel storage, and quarters for the airship crew. The trials were successful, and attention then turned to another first, a transcontinental flight that would be the first extended operation away from Lakehurst. Only three masts were available, at Fort Worth, San Diego, and Fort Lewis, Washington. The initial leg to Forth Worth went well, but crossing the Continental Divide posed a problem. The gas cells were filled to be about 85% full at sea level, but as the airship gained altitude they would expand, and at a certain point, the automatic vents would release helium to prevent the cells from rupturing. The helium shortage meant that this was avoided if at all possible, and to keep losses to a minimum, Shenandoah was piloted through a pass in the mountains instead of flying over them. She reached San Diego safely four days after setting out, and spent 11 days operating on the Pacific coast, including a trip to Seattle.

Shenandoah flies over Long Beach during her trip to the Pacific

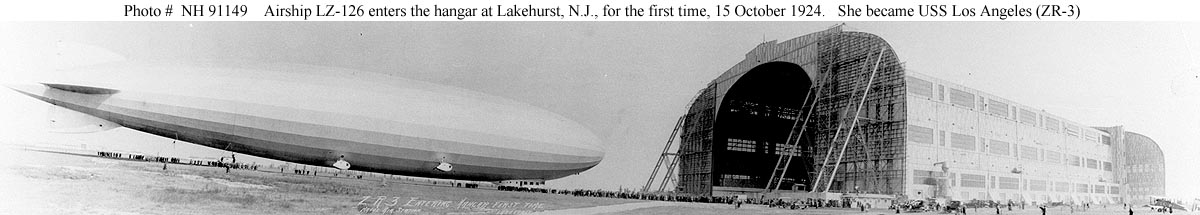

The return trip to Fort Worth was even more difficult, as the airship had to be fully fueled for the journey, and the mountains were nearby. To avoid dropping ballast, which would in turn require helium to be vented when landing, Lansdowne chose to fly his ship as much as 13° nose-up, producing considerable aerodynamic lift, but imposing unknown and unanticipated strains on the structure. Despite this, the transcontinental trip was a success, and Shenandoah was greeted on her return by ZR-3, which had arrived directly from Germany. As the German airship was officially intended for civilian use, her passengers were distinctly more comfortable than the crew of Shenandoah, who subsisted on sandwiches and soup. But the helium shortage still bedeviled operations, and Shenandoah was ordered to be deflated and her gas transferred to the new airship, christened Los Angeles.4

ZR-3 arrives at Lakehurst

While Los Angeles was bigger and more advanced than Shenandoah, she was still a bit too small for proper oceanic operations, and there were legal concerns about using her for military purposes. As a result, her early operations were primarily to train personnel and test the possibility of airships in commercial service, including several nonstop flights to Bermuda and Puerto Rico and back. Other problems reared their heads. Her gas cells, made from goldbeater's skin (cow intestine membrane) were getting old and leaking the vital helium, while supplies of spare parts were hard to come for the cash-strapped lighter-than-air program. As a result, by June 1925, the decision was made to overhaul Los Angeles and put Shenandoah back into service.

While she had been out of action, Lansdowne had made a number of modifications to lighten the ship and reduce the loss of helium. Many of the automatic valves were removed, putting the cells at risk of rupture if she rose too quickly. A planned publicity trip to the Midwest was delayed from June to September due to the risks of hot weather and summer storms, and Shenandoah spent July and August operating with the fleet, including the first tests of strategic scouting, refueling at sea, and even using her as a tug for anti-aircraft targets. But on September 2nd, Shenandoah cast off on her 57th flight, bound for St. Louis, Minneapolis and Detroit. While over Ohio, she ran into a thunderstorm, which tried to hurl her high into the air, despite the use of full power by her engines. Substantial amounts of helium had to be valved off before the airship ran into a downdraft. Even dumping several tons of water wasn't enough to arrest her descent, and at 3000', she was again hurled upward by an ascending air current. The stress on her structure proved too much, and she snapped in half, throwing several of the riggers who had been working in her keel into the sky. The control car broke away, killing Lansdowne, and aft section fell nearby. The men in the buoyant forward section were able to bring it gently to earth an hour later by carefully valving off helium.

Thanks to that inert gas, only 14 of the 43 men aboard died, but the fact that the Navy's showpiece airship was scattered across a large part of Ohio would have wide repercussions.5 Surprisingly, the Navy's lighter-than-air program would survive the negative publicity, and even go on to receive two more airships. We'll take a look at that next time.

1 Z was the letter the USN used for all lighter-than-air programs, probably coming from Zeppelin. ZR was for rigid airships. ZR-1 was Shenandoah, discussed later. ⇑

2 Most of these publicity trips were in the Midwest, probably at least in part because it is regrettably difficult to bring warships into these parts for public display. ⇑

3 One interesting device installed during this overhaul was a water-recovery system. As fuel burns off, airships get lighter, which would normally mean they'd need to vent gas. To reduce this requirement, the water-recovery system would condense water out of the engine exhaust and store it aboard. ⇑

4 While designed from the start for use with helium, ZR-3 was tested in Germany and delivered across the Atlantic using hydrogen. Also, the Arctic trip was cancelled at some point around this time. ⇑

5 One notable result was Billy Mitchell shooting his mouth off and getting court-martialed for it. ⇑

Comments

When you read about men parachuting out of airships so he can teach the ground crew to get it landed safely, you start to realize why so many things spontaneous exploded back then:

They were just so much cooler.

It's all sort of like the current SpaceX ships. Marvelous wonders of modern engineering, but every time it lands without exploding you cheer.

Certainly NOT what you want for service in a military environment. Or a civilian passenger service either.

Starship blows up every time because it's still in an extremely early developmental stage, but Falcon 9 has definitely reached a level of reliability that makes it acceptable for national security payloads and civilian astronauts.