After WWI, the US Navy was by far the world leader in naval lighter-than-air aviation. It first attempted to buy airships from Europe, but these plans fell through, and its first rigid airship was the American-built Shenandoah, the first airship to fly from coast to coast. She was joined by the German-built Los Angeles, but broke up in a storm over Ohio in October 1925.

Los Angeles over Manhattan

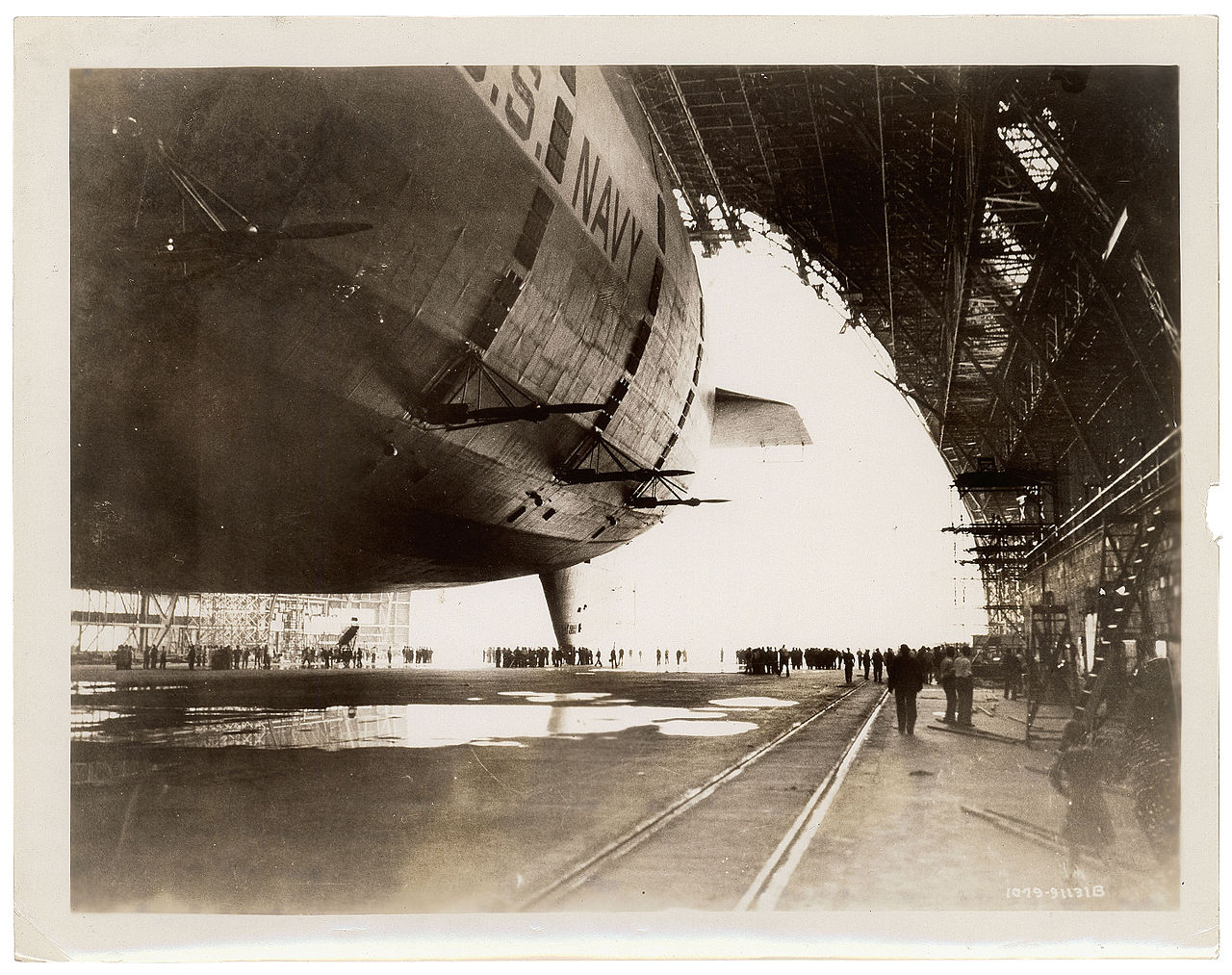

Despite the disaster, the Navy's lighter-than-air program survived, although it remained on a fiscal shoestring for the rest of its life. Because Shenandoah's loss resulted in most of the program's helium escaping, Los Angeles was grounded until March 1926. But her return to flight, under the command of Charles Rosendahl, the senior survivor of the Shenandoah crash, allowed the USN to begin the practical work of learning how to operate rigid airships. Rosendahl, an aggressive and charismatic officer with a boundless faith in the possibilities of lighter-than-air flight, was the perfect choice for the job. In the early days, the techniques for handling the ship on the ground had been limited to the use of hundreds of men to walk the airships in and out of hangar. Occasionally, things would go wrong, and the airship would lift too early, carrying some of the ground crew with it. They were under strict orders not to let go if this happened, as it would make the problem worse. Later, a rail-mounted stub mast was developed, which would hold the airship at the nose and tail. It would be pulled out of the hangar to a "mooring-out circle", where the nose would be pointed into the wind, and the tail released, allowing it to take to the air gracefully.

Macon being moved out of the hangar at Lakehurst

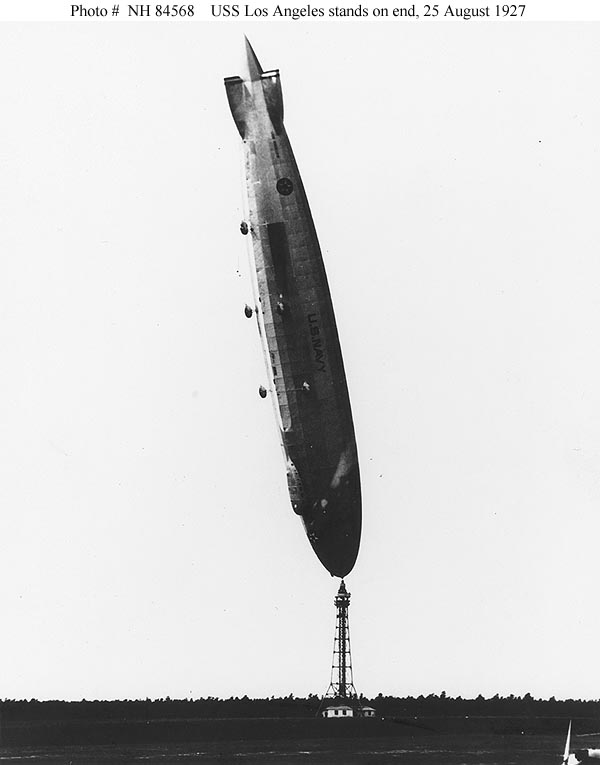

Another innovation was the use of stub masts in place of the high masts that had been developed by the British. The downside of the high mast was that the airship was, for all practical purposes, still flying, and had to be operated as such. This was dramatically demonstrated on August 25th, 1927, when Los Angeles was at the high mast at her base at Lakehurst, New Jersey. A sudden shift in the wind let a burst of cold, dense air get in under her tail, pushing it up. The officer of the watch ordered men aft, but before they could respond, the wind under the now-tilting airship combined with the extra buoyancy from the air to lift the entire airship close to the vertical, the crew hanging on for dear life as equipment rained down past them. The airship rapidly cooled, and within seven or eight minutes was back on an even keel. The airship had taken some minor damage, but was surprisingly unharmed. To avoid this kind of problem, the high mast was supplemented with a stub mast. The stub mast was short enough that the airship's rear fin could rest on the ground, with a bit of weight to keep it there. A tire under the fin allowed it to weathervane around, much as it did on the high mast.

Los Angeles near vertical

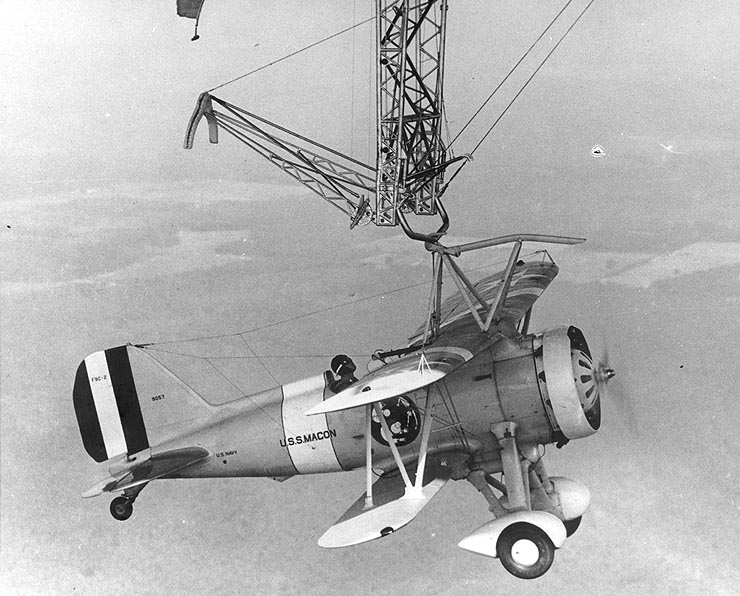

But the trials run with Los Angeles went far beyond just ground handling. In addition to a series of long-range missions to test broader operations, she served as a testbed for the use of airships as carriers for heavier-than-air planes. The idea was to combine the speed of fixed-wing planes with the range and endurance of the airship, and initial trials, using a trapeze hung below the airship and a hook on the plane, went fairly well. After the technique was perfected, pilots reported that it was easier than landing a plane on a runway, much less on a carrier deck.

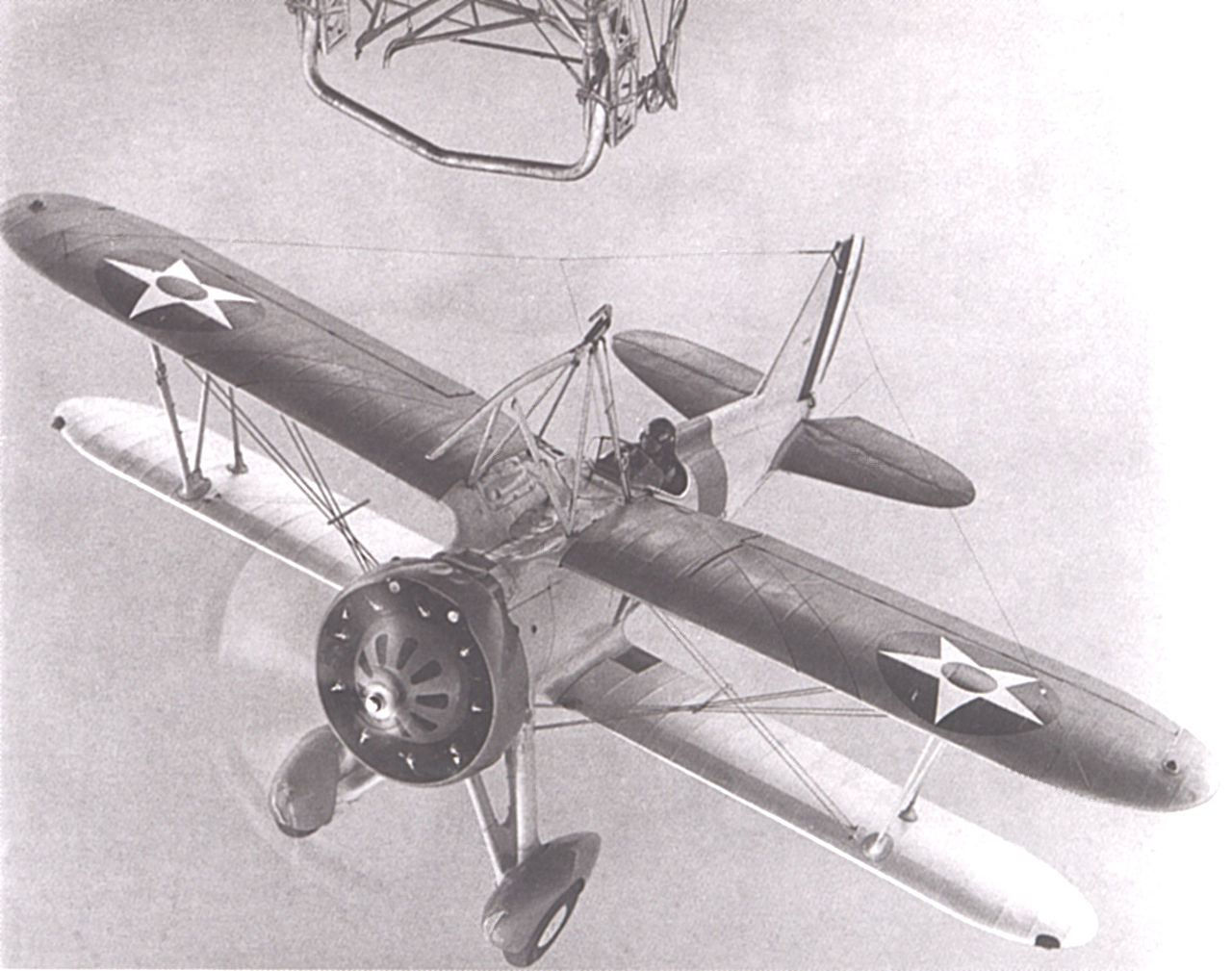

An airplane on the trapeze below Los Angeles

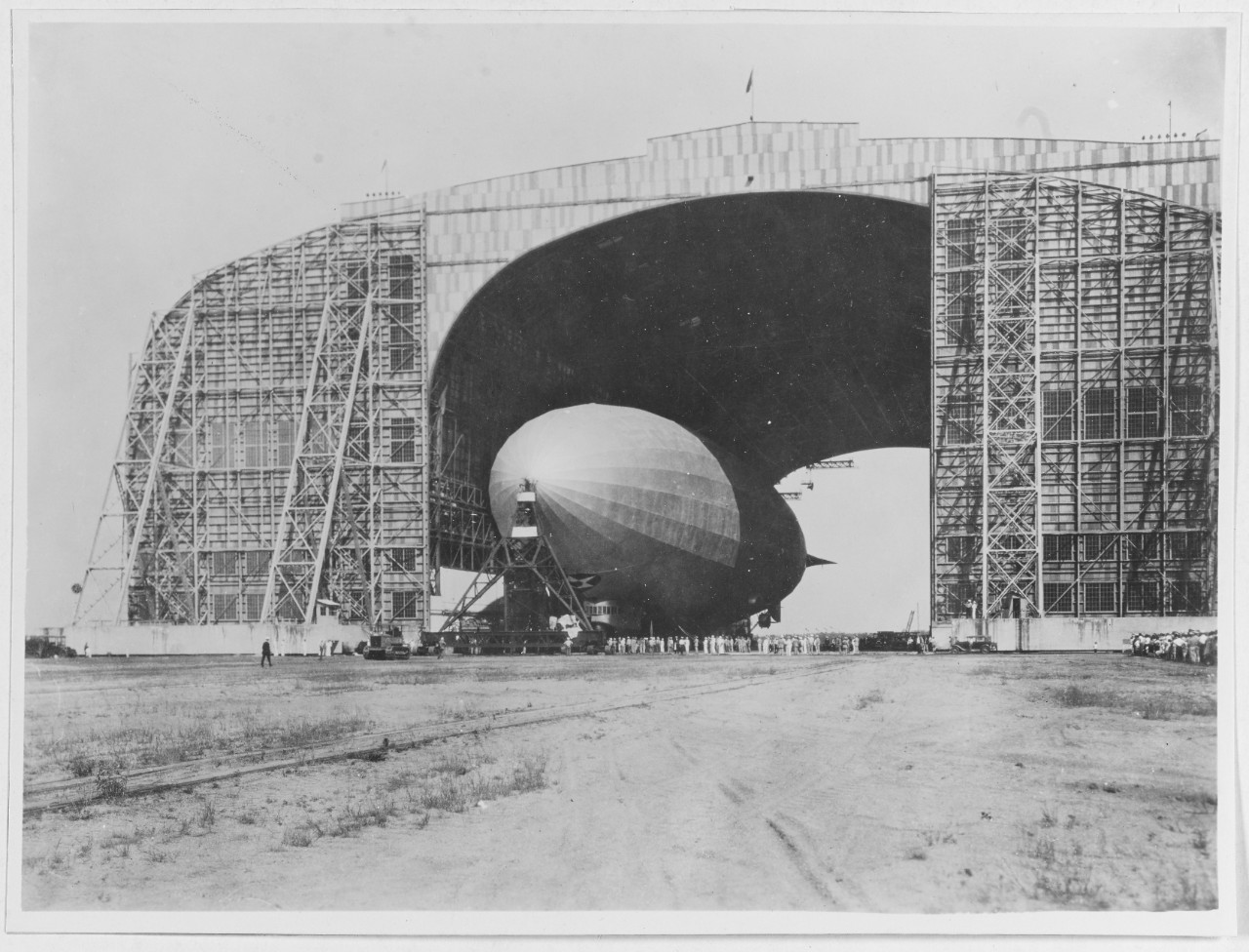

In 1927, Congress finally authorized more airships. Two vessels of a new design would be built by a partnership between Goodyear and the Zeppelin Company, and assembled in a giant hangar in Akron, Ohio.1 These would be twice the size of Los Angeles, fully suitable for strategic scouting, and fitted with an internal hangar for five airplanes each, the only airships ever built to carry airplanes. The use of helium also allowed them to have their engines mounted inside the airship envelope. This improved aerodynamics and gave the mechanics much better working conditions, but the biggest advantage was that the propellers could be pivoted to point downward instead of backward. This, combined with the ability of the Maybach engines to reverse, gave the captain the option to use thrust when taking off heavy or landing light. Another innovation was the fitting of condensers not just to the engines but on the side of the envelope, allowing the ships to gain weight while in flight and thus reduce valving of helium.

Los Angeles during her attempted mooring with Saratoga

Even as the new airships, Akron (ZRS-4)2 and Macon (ZRS-5) were being built, Los Angeles continued development work. The restrictions on Los Angeles to civilian use were finally lifted, allowing her to participate in Fleet Problem XII in 1931, the first time an airship had operated with the fleet since 1925. She was successful in finding the enemy, but was "shot down" by planes from the defending fleet. The only major failure in this period was a 1928 attempt to refuel from the new carrier Saratoga, which was aborted after a few minutes due to turbulence.

ZMC-2 in flight

Nor were Akron and Macon the only new airships to arrive at Lakehurst in this era. The Navy also bought ZMC-2,3 the world's only metal-skinned airship. It had a skin of 0.080" alclad aluminum, held together with 3 million tiny rivets. It was likely largely supported by internal pressure, although sources are not clear on how important this was.4 Buoyancy control was provided by a pair of ballonets, which could be pressurized with outside air to increase the density of the craft, or emptied to increase lift. ZMC-2 proved reasonably successful on its first flight in 1929, although its builder, the Detroit Aircraft Corporation, didn't survive the Great Depression and it was mostly used as part of the extensive training program going on at Lakehurst to support the Navy's burgeoning lighter-than-air program. Students learned first in free balloons and then in a handful of blimps before being assigned to one of the rigid airships for operational service. ZMC-2 itself remained in service for a decade, and was broken up in 1941.

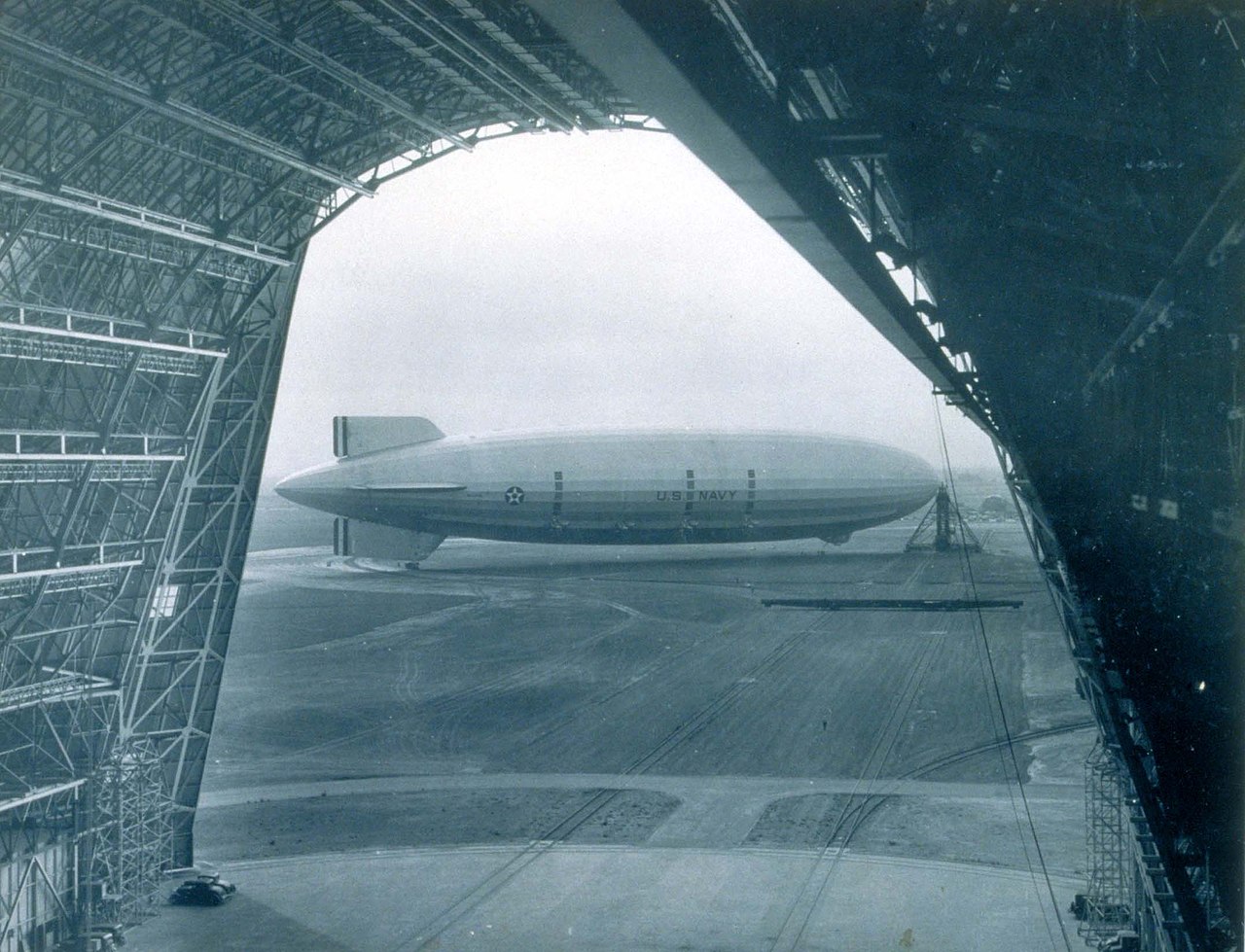

Akron in the Goodyear-Zeppelin Airdock

When Akron was commissioned on Navy Day 1931, the USN had, for the first time, two operational rigid airships, and they flew together over New York. But fiscal constraints still dogged the program, particularly in view of the Depression, and Los Angeles was taken out of service in June 1932. She was the only one of the Navy's rigid airships to be decommissioned, and she was carefully preserved in case they decided to reactivate her later. Akron was dispatched to test strategic scouting with the fleet. Her trapeze had yet to be installed during the first exercise in January 1932, and while she did find the destroyers she was looking for, it took two days, despite passing within 15 miles of the ships on the first day. A follow-up exercise on the West Coast was cancelled when her tail broke loose while being moved on the ground and required two months to repair.

An F9C hooks onto a trapeze

That summer, the trapeze was finally installed, and operations began with her intended F9C Sparrowhawk fighters. The F9C had originally been designed as a small carrier-based fighter, but proved unsuitable in that role. It was, however, small enough to fit into the hangar on the airships, and as the only suitable aircraft available, it was selected for the job. The purpose of the Sparrowhawks was not entirely clear to the participants. The pilots of the fighters believed that their main mission was to extend the scouting range of the airship, allowing the vulnerable zeppelin to stay well away from the enemy. The airship proponents focused primarily on the defensive role of the fighters, refusing to accept their demotion to a simple carrier. The error of this view should have been obvious after Akron made it to the West Coast and was repeatedly shot down by the floatplanes of the fleet when attempting to do direct scouting, but the Sparrowhawks weren't available yet, and Rosendahl, now captain of Akron, claimed they could have protected his command. Others did not consider her participation nearly as successful.

William Moffett

Akron returned to the East Coast, and after a set of flights to scout winter operating bases in Florida, Cuba and Panama, returned to Lakehurst. On April 3rd, 1933, she departed on her 74th flight, a routine training mission. Aboard were 76 officers and men, including Admiral Moffett, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics and a strong proponent of the airship. The weather report looked clear, but a surprise cold front appeared, bringing with it a severe thunderstorm. The airship was thrown around violently, and eventually the rear fin hit the water. The sea began to flood in, dragging the airship further down, and only three of the men aboard survived, rescued by the German merchant ship Phoebus. Moffett was not among them, and it was the beginning of the end for the rigid airship in the US Navy.

Macon operates Sparrowhawks. The black stripes are a water recovery system intended to minimize venting of helium

Macon's first flight came less than three weeks after Akron went down, and when she left Lakehurst six months later, it was the last time a naval rigid airship ever operated there.5 Macon was bound instead for the new naval airship station at Sunnyvale, California, soon rechristened Moffett Field in honor of the deceased Admiral. The hangar built to accommodate the airship was one of the largest buildings in the world without interior supports, and it remains a major landmark in Silicon Valley today. Macon was nearly identical to Akron, although detail improvements meant she was 8,000 lbs lighter and 3 kts faster than her sister.

Macon seen from inside Hangar 1 at Moffett Field

Macon spent the end of 1933 and the first months of 1934 busy supporting fleet activities, including a trip to the Caribbean in the spring. During the transcontinental voyage, she suffered structural damage, and repairs had to be made at the expeditionary mast in Florida. During these exercises, Macon was usually attached to one of the fleets and used as a tactical scout, a role that didn't particularly play to the airship's strengths. In mid-1934, Lt. Cmdr Herbert Wiley took command, and began intense development work with the F9Cs, which had previously been limited to operating within visual range of Macon. That July, she intercepted the cruiser Houston, bearing President Roosevelt from Panama to Hawaii, 1,500 miles out at sea. The sight of a pair of planes appearing so far from land startled those aboard the cruiser, as did the dropping of mail, and even the winching down of newspapers as the airship matched speed with the surface vessel. This operation was also notable for Wiley's decision to remove the landing gear from the Sparrowhawks. There was no way they could make it to shore if they had problems, and it significantly increased speed and range, as well as making ditching safer.

An F9C approached the trapeze aboard Macon

On February 11th, 1935, Macon was dispatched to search for units of the fleet that were heading from the Long Beach area to San Francisco, a task she performed successfully. The next day, while operating off Point Sur, she was struck by a gust of wind that tore the structure near her upper fin, an area that had been identified as needing reinforcement after the trip to Florida, but the work had yet to be carried out. The broken frame punctured the two aft gas cells and threw the airship out of control. Despite the crew's best efforts, they were unable to control Macon's nose-up attitude, and Wiley made the decision to ditch. The landing was rather gentle, with plenty of time for the crew to don lifejackets and throw rafts overboard. Only two of the 83 men onboard were lost, but it was the end for the naval rigid airship.

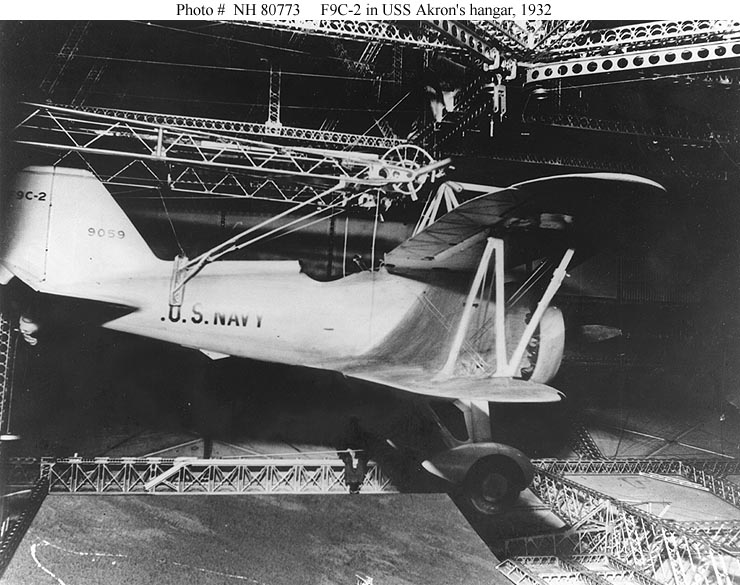

An F9C in the hangar aboard Akron

Various proposals had been made to replace Akron, but none had come to fruition. Los Angeles was put back in limited service for tests and ground handling training, but while she was close to being flyable, no serious effort was ever made to actually put her back on flight status. Instead, she was finally broken up in 1939. With Macon's loss, the whole program was dead for good. And while it's an interesting what-if, this was probably for the best. Airships had proven themselves hideously vulnerable to bad weather, particularly as their slow speed made it much harder to run for home if a storm blew up. And while the idea looked promising in the 1920s, by the mid-30s fixed-wing aircraft were getting to the point where they could perform the strategic scouting mission on their own, and a PBY Catalina was vastly cheaper and less vulnerable than a rigid airship.6 Ultimately, it was an interesting idea, but one that was rightly abandoned by history.

Los Angeles emerges from the hangar at Lakehurst

But Macon settling into the Pacific didn't mark the end for the USN's entire lighter-than-air program. Instead, it would endure for another two decades, but with a rather different focus, as a handful of rigid airships gave way to the numerous blimps that would patrol American coasts during the coming war.

1 The president of Goodyear was a big believer in the airship, and the company had been involved in American airship efforts during WWI. The Goodyear Blimp originated as a training program for crews for a projected commercial airship. ⇑

2 The S apparently stood for Scouting. Also planned were ZRN (training) and ZRP (patrol) airships. ⇑

3 The 2 in the designation referred to the 200,000 cubic foot capacity. There was no ZMC-1. ⇑

4 I'm pretty sure it was significantly more durable than the balloon tanks used on the Atlas rocket, which would collapse if they weren't kept pressurized at all times. ⇑

5 Lakehurst did serve as the American terminal for transatlantic passenger flights by Graf Zeppelin and, memorably, Hindenberg. ⇑

6 Another aspect in the strategic scouting picture was the USN's heavy investment in radio direction-finding, which wasn't vulnerable to bad weather and could watch the entire Pacific at once. ⇑

Comments

Always wondered if all of these guys were volunteers, or if some of the crewmen were just told "hey yeah, you're on guaranteed deathtrap duty".

As far as I know, they were all volunteers. And no, there's not a word missing that I can tell.

Speaking of blimp hangars, I once visited Tillamook Air Museum, housed inside a former blimp hangar, which saucily notes that it is "the largest clear-span wooden structure in the world" (IIRC they also say it's the largest wooden building in the world as measured by volume, which feels like cheating). The airplane collection isn't anything terribly interesting (although it's all pretty random stuff, and thanks to competing interests between two collections, notably free of the standard group of WW2 warbirds), but Hangar B in and of itself is pretty impressive and worth the look.

The Fatherly One has been there, too. I haven't, sadly, but Tillamook is coming in a later part (don't know which one yet, because I haven't written it yet).

I'm guessing the missing word is

radio direction-finding, which wasn’t vulnerable to bad weather and could watch the entire Pacific at once.

Ah. I sort of assumed it was obvious, but that's just because I've been doing this too long. Will fix.

echo:

I doubt they realized it was deathtrap duty at the time.

It wasn't guaranteed deathtrap duty. Through 1940, the USN trained 157 LTA officers, and only 27 of them had been killed on airship duty. A man was just as likely to retire safely as to be killed in an airship! (The majority were still on active duty.)

@Blackshoe

How else would you sort very large buildings? : )

In all seriousness, being the biggest wooden building mostly just requires them having a very good fire-control system.

A link to [one]]https://www.navalgazing.net/Information-Communication-and-Naval-Warfare-Part-1) of these might also help.

@ike

In the Navy, Firecontrolmen are the people who aim the guns, and Firemen are engineering department unrateds (probably called that because they used to shovel coal into the boilers). Specialist firefighters are probably Damage Controlmen.

(Not a criticism (and you're not the first), mostly me being amused that the (US) Navy has two job titles that sound vaguely like a firefighter and neither of them actually are.)

I frequently had to start off my description of my job as "Fire Control Officer" by noting "No, I don't do what it sounds like I do."

I had the confusion over what "fire control" meant a lot when I was tour guiding. Including from my mother.

Ah, that makes sense. I didn't even think about radio direction-finding for finding enemy fleets, but ofc there were a few decades there where nobody had invented emissions control, weren't there?

there were a few decades there where nobody had invented emissions control

Well we had those stories about the British fleet at Jutland not communicating with each other because they were trying to maintain radio silence. But the result was that they couldn't communicate.

Not really. The British invented it before WWI (and took it rather too far, actually), and most everyone figured it out reasonably quickly thereafter. (Except the Germans, but that's a different story.) The Japanese used it when they hit Pearl Harbor, for instance.

bean:

That still looks like a really high fatality rate, even for that era and it was doing something that doesn't really look all that dangerous (peacetime and not a line of work where training being more dangerous than war is a point of pride).

I was being facetious there. The fatality rate definitely seems high to me, although in fairness, I don't have figures for regular pilots in that era. I think it had fallen off by then, but I wouldn't be astonished if it was in the same ballpark as LTA.

Around 25 USN airplane deaths/year, but I don't know how many that's out of. (Pilots aren't quite the right category since Navy planes aren't all single-seat.)

Or if we're comparing to the Navy as a whole, around 300 accidental deaths/year, but again I don't know how many that's out of.

Source, also includes brief descriptions of some accidents (which they note were selected partly by whether information was conveniently available).

I see in one photo of the Macon at Sunnyvale it only has 3 condensers installed. Eventually it had 4 per side as did the Akron. Do we know why and when this took place?

Thank you

I actually think it was initially installed when she was initially built, then removed. The book Sky Ships has pictures of her with four through October 1933, when she moved to Sunnyvale, then the next photo, dated May 1934 (during a deployment to Opa-Locka, FL) has her with only three. Unfortunately, it's the last of the outside of the ship in the book. The most obvious candidate explanation is that they found they could get sufficient performance out of three condensors and so removed the fourth.