The maritime world uses a very different set of measurements than those used on land every day. Where did they come from and what do they mean?

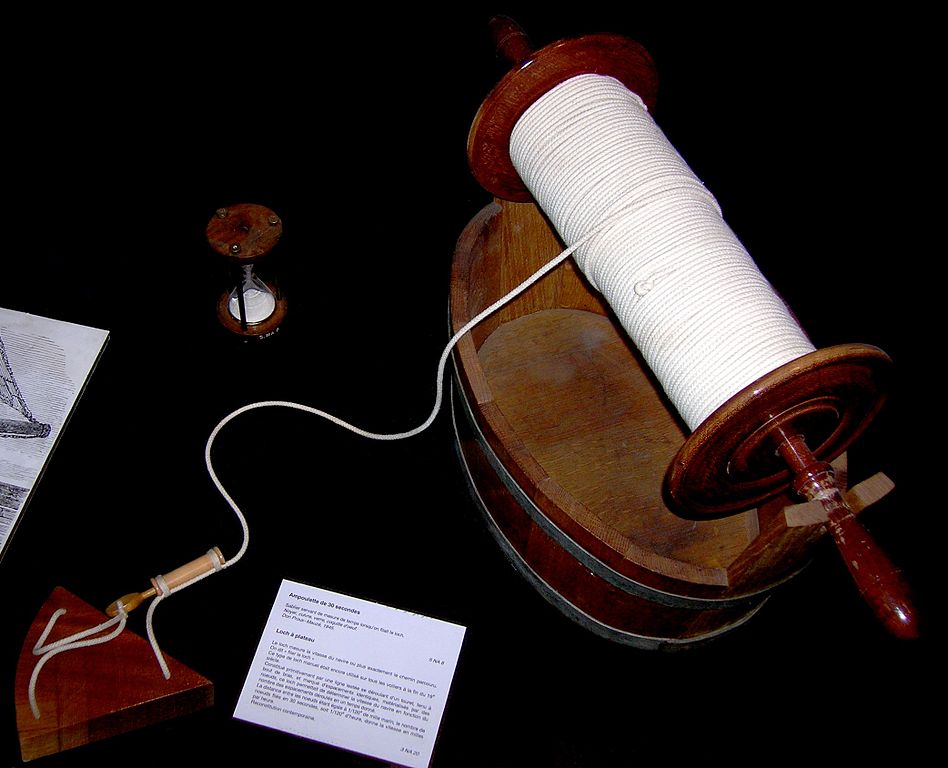

A Chip Log

Distance is measured in nautical miles, which can be seen as a spiritual predecessor to the meter, both units initially being defined as some fraction of the distance from the equator to the pole.1 Specifically, the nautical mile was long defined as equal to one minute (1/60th of a degree) of latitude. Today, it's defined as 1,852 m, or 6,076 ft. It's used by both the nautical and aviation2 communities as a world standard.

The knot, the standard unit of speed, is simply 1 nautical mile per hour, but its name comes from the method of measuring speed used up through the 19th century. A device called a chip log was thrown over the side, attached to a rope with knots in it. The chip log was designed to stop in the water, and it would pull the rope off a reel. When it was thrown, a 28-second sandglass was turned, and the number of knots that were pulled out was counted.3 Nautical miles per hour is rare, and knots per hour is a unit of acceleration, although it was common to use it interchangeably with knots until about 1900, after which it fortunately died out. Other measurements for ship speed are very rare. Even in reference books that are otherwise completely in metric units, speed is always given in knots.

Now we come to tonnage. This is a horribly confusing unit, particularly as one starts to look at civilian shipping, as it can mean totally different things in different contexts.

The easiest tonnage to understand is displacement tonnage. This is the actual weight of the ship, called displacement because the weight of the ship is equal to the amount of water it displaces, per Archimedes' principle. Of course, the displacement of a ship can change greatly depending on what's aboard, so several different displacements are often used. A good reference will usually give three values: light, normal, and full. Light is basically an empty ship. There are some technical details, but in essence it's what the ship weighs if we take all the people, fuel, cargo, ammunition, and supplies out of it. Full displacement is exactly what you'd expect from the name. The ship is as heavy as it's ever going to be, with full fuel, ammo, and cargo. Normal is essentially a ship with full cargo and crew, but two-thirds fuel and ammunition. On warships, it's common for light displacement to be 75% or so of full displacement, so it's obvious that a poor choice of reference numbers can cause confusion about the actual sizes of the ships in question. Displacement tonnage in non-metric references is always given in long tons of 2,240 lb each. This is to allow easy conversion, as a long ton of salt water has a volume of almost exactly 35 cubic feet. I'm not sure what metric references do.

The only other displacement value used for warships is standard displacement, a creation of the Washington Naval Treaty. Intended to provide a baseline for limiting the size of warships, it was defined as displacement “complete, fully manned, engined, and equipped ready for sea, including all armament and ammunition, equipment, outfit, provisions and fresh water for crew, miscellaneous stores, and implements of every description that are intended to be carried in war, but without fuel or reserve boiler feed water on board.” The lack of fuel, excluded because the US argued that it was unfair to penalize their ships, which had to fight in the Pacific, over those who didn't have the same range requirements, means that treaty standard displacement bears only a vague resemblance to other displacement numbers. Usually, the actual loaded displacement was about 25% above treaty displacement. For instance, Iowa was designed to be around 45,000 tons standard, but displaced 57,000 tons when she was fully loaded. Comparing standard and real displacements is a fairly common mistake, and ships built after WWII don't have a standard displacement at all.4

Displacement tonnage is the only tonnage value commonly used for warships, while merchant ships instead use a completely different set of tonnages, usually deadweight tons, gross tons, and net tons. Deadweight tonnage is at least an actual measure of weight, and specifies how much cargo the ship is able to carry, excluding the weight of the ship itself. Gross tonnage and net tonnage are both basically volumetric measures, specified using complicated formulas.5 Gross tonnage is based on the total volume of all enclosed spaces of the ship, while net tonnage is based only on the volume of the spaces that carry cargo or passengers. These values are used to calculate things like port duties and what regulations apply to the ship. They replaced gross and net register tons, which were also volumetric, of 100 cubic feet to the ton.6 These were based on a phenomenally complicated set of rules to determine what spaces were and weren't counted, with shipowners trying to game the system and drive down their tonnage. Worse, different countries had different regulations on what counted under each value, so in 1969, register tonnages were abolished and replaced with the current system.

While distance, speed, and "tonnage" measurements are the most prominent nautical idiosyncracies, there are a few other values that bear mentioning. The maximum width of a ship is the beam, apparently from the beams that used to run across ships during the days of sail. Draft (or draught) is how deep the hull is below the waterline. This is a very important number to make sure the ship doesn't run aground, but it varies continually with the amount of stuff on the ship. Air draft is the term used for the height of the top of the ship above the water, important for clearing bridges and the like. Length, much like tonnage, comes in several values. The obvious one is length over all, LOA, which is exactly what it sounds like, measured from the furthest forward to the furthest aft point on the ship. This is obviously useful, but for hydrodynamic purposes another value, waterline length (LWL), is what the designer cares about.7 The last value is length between perpendiculars (LBP), measured between the vertical stem (bow) post and the vertical stern post. This is another value that was developed for civilian use. Some ships of a given LOA have a great deal of overhang at bow and stern, making them much smaller than other ships with the same nominal LOA. Using LWL is not a good solution, as it varies with draft. LBP solves both of these problems, but isn't of great importance to warships.

Nautical terminology is often confusing and even contradictory. It's also the result of centuries of development, mostly independently of the activities of the terrestrial world. I hope I've not only helped clear up confusion about what these terms mean (except for tonnage, which is just hopeless), but also given a glimpse of the world centered around the sea.

1 The meter was supposed to be one ten-millionth of this distance, but the Earth isn't perfectly spherical, and there were some calculation errors, too. ⇑

2 For reasons I'm not quite sure of offhand, aviation adapted a lot of practices from the nautical world. ⇑

3 Each knot was 47'3" apart, which is equal to the distance of the nautical mile multiplied by the ratio of the 28-second glass to the 3600-second hour. ⇑

4 And all of this ignores both the rather amusing games played with treaty tonnage by designers trying to get their ships under the required weight, and the fact that certain navies (most notably Japan) took a rather more relaxed view of their treaty obligations than others. ⇑

5 There's some vague sense to this, because both values derive from the same source, the tun, a very large cask that held around 2,000 lb of water or wine. The weight of water carried became a weight ton, while the volumetric tonnage was intended to approximate how many tuns could be carried. There's also BOM tonnage, which is a simple volumetric formula that went away in the mid-19th century. ⇑

6 Note that each volumetric ton, if filled with seawater, would weigh almost three weight tons. ⇑

7 To a first approximation, the water doesn't care about anything that isn't touching it. ⇑

Comments

@bean

Navigation is my guess. Older small civil planes (Cessnas, Pipers, etc) often had instrumentation in statute mph, as did WWII aircraft, I think.

If you look at this P-51 cockpit, the ASI is denominated in mph, not kts. https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?id=NASM-NASM2015-06200

However, navigation was always done in nautical miles, and eventually they standardized on knots. (Apparently some of the pre-WWII airliners carried an mph ASI for flying, and a kts ASI for navigating, which seems excessively complicated, but I suppose human factors analysis wasn't what it is today.)

That makes a lot of sense. Nautical miles are really helpful for navigation. I actually end up having to use the fact that they're easy to convert to DMS quite a bit at work, for back of the envelope "how big of a deal is this?" questions.

Yeah, knots/nm in aviation is strictly a navigation thing. And the field finally purged itself of statute miles in the early 1980s, IIRC, which is about the time navigational technology reached the point where no one would ever have to do spherical trigonometry by hand calculation again. But, since we've finally got one consistent set of units, we're not going back (and there's little pressure to go forward to SI).

bean:

A nautical mile is only an arc-minute if you're referring to lines of latitude, the equator or a great circle, if you want to work out the distance between 10° longitude at constant latitude not on the equator it doesn't make it mental calculations any easier.

John Schilling:

Maybe not now but in the long term it's going to happen, at the very least using different units for aviation and sea navigation increases the learning curve (slightly admittedly) needed before being able to do it compared to using metres and kilometres which are familiar measurements, at least if you're outside the US and UK.

I'm well aware of that. My usual use is something like "Right, these two systems disagree by .001 minutes. That's about 6 feet, and in this application, we don't need to worry about that." The fact that it could be less than 6 feet is immaterial, because it's a worst-case scenario anyway.

I'm with John on SI units. At sea, everything is in knots/nautical miles, and the fact that a nautical mile is very close to 6,000' means that it's fairly easy to interconvert in practice.

Didn't the US military have to go metric back in the seventies? I guess that would be helpful when working with allies.

bean:

That assumes you're one of the few people still using feet.

It also assumes that there's no need to operate with other environments, e.g. land where km and km/h are the units of measure for most of the world.

Johan Larson:

Only partly, just like the rest of the US.

Some US allies decided they had to go metric because the US announced that they were going to switch, something about it being very expensive to be last to switch.

Great article Bean as always.

The 1/60th aspect happenes to also be useful in other areas of aviation. We have the 60 to 1 rule and it helps when flying an arc from a navigational aid. Or perhaps I should say that it was useful in my military flying days whereas now the "glass cockpit" (the displays) have sadly pushed those NM distance rules of thumb into the background a bit.

As far as the use of feet we still use it for altitude almost the world over. China and some others are still metric for all altitudes and I find it a pain for a number of good reasons. Visibility and everything else is fine in meters, but altidudes work very well in feet.

For what I do, the unit doesn't matter. It's usually a case of how much we need to sweat over a disagreement between two numbers, and when you're working on a jet, it doesn't matter if my back-of-the-envelope works out to 2m, 6', or 10'. In all cases, they're well within the noise of various systems recalculating things.

Again, for what I personally do, this isn't a concern. In an ideal world, everyone would use a single unit, but we're stuck with the world we have, and in the air and at sea, knots are standardized enough that we don't care.

Totally unrelated to this post, but some months ago you made a request for contributors, and I offered to write up a museum review for HMS Victory and HMS Warrior due to a then-planned vacation. I've now been, and as a bonus I went to see HMS Belfast in the middle of London as well. (My wife was very patient with me this trip)

So, bean, how would I go about actually getting these posts up? Is there an email address I should poke you at? Thanks.

@Alex

My email is battleshipbean at gmail. What happened when DismalPseudoscience did his review of Mikasa was that he wrote up his review in the style I use for mine, then sent it to me in a google doc. I loaded it into the blog and handed him an account so he could look at it. It worked pretty well, although if you want to do it differently, I'm not demanding this method be used.

Silly question, but why a 28-second sandglass?

Not sure. I think it was originally supposed to be 30 seconds, but it ended up as traditionally set at 28.

On units of speed: Inland waterways (including the Great Lakes) use miles per hour- I know someone who has put an automotive GPS on his cabin cruiser, which was built as a seagoing vessel but is kept on the Norfolk Broads, because its own instruments read in knots and the speed limits are in mph.

There is also the possibly-apocryphal story of the clipper-ship sailor who reported the ship's speed to the officer of the watch as "sixteen knots and a Chinaman"- the chip log had not only run the line out to its full extent, but then pulled the (Chinese) sailor who was holding it overboard!

On LOA vs. LWL- this became important in the design of 1930s racing yachts. Class rules limited LWL (measured when stationary and vertical), so the yachts were built with very long bow and stern overhangs, then sailed with enough heel that they had one rail in the water, dramatically increasing their waterline length and therefore speed.

This kind of thing is why I'm suspicious of fresh water. It does weird things to people, like making them use the wrong units.

Racing always produces interesting stuff like that, where people are pushing the regulations to try to win. My favorite is the 1988 America's Cup, where the challenger insisted on a Deed of Gift match, in accordance with the rules under which the Cup challenge was set up, instead of negotiating the rules, as was traditional. They already had a yacht built to those rules. The defender realized that the deed didn't say they needed to use a monohull, and proceeded to resoundingly beat the challenger with a catamaran.

If I read about how many "tons of shipping" a commerce raiding campaign sank, which tons are those? (Assuming this is consistent...)

Most likely, it's gross register tons. Finding displacement tons for merchant ships is usually nearly impossible, actually.