In the 1930s, the USN began to set new standards for habitability aboard its ships, including in the area of food. The traditional mess system, where men ate in the same place they slept, was abolished, replaced with so-called cafeteria messing, first tested on the carrier Ranger. Men would simply come to the mess decks from their berthing compartments (which could be fitted with fixed bunks instead of hammocks), stand in line to fill their trays, then eat at permanent tables. There wasn't enough space for everyone at once, but men dealt with this by spreading out service. Meals were normally served at 0730 (breakfast), 1200 (dinner) and 1800 (supper), times which corresponded to when the watch was changed, allowing those about to go on duty and those about to come off duty to eat.1 When not in use for eating, the mess decks were a place for men not on watch to socialize and pass the time. The cooks would usually put out leftovers or sandwiches around midnight for those who had the midnight watches. This was known as "midrats", derived from midnight/midwatch rations, although it was an informal affair.

Cooks aboard Missouri prepare lemon pies for the crew

The new ships also had vastly improved kitchens. Even small ships like destroyer escorts had ice dispensers for the men, diswashers, potato peelers, and ice cream machines. The result was quite a good diet for the men of the US Navy. For breakfast, a sailor could in theory expect fruit, cereal, bread and a hot dish, changed daily. It might be pancakes and bacon, or eggs and ham, or baked beans and biscuits. To wash it down, milk and coffee were available. A typical dinner menu might be roast lamb with mint sauce, scalloped potatoes, fried carrots, grapefruit and green pepper salad, vanilla ice cream, whole wheat bread, butter, and coffee. For supper, he'd be offered cream of chicken soup, baked luncheon meat, sliced cheese, cardinal salad, chocolate cake, a roll, and tea. The exact ingredients obviously varied, but the overall picture of a meat dish, starch dish, fruit/vegetable dish, bread and dessert was pretty consistent, with a soup at one meal or the other.2

Sailors on New Jersey line up abovedecks to get into the mess

The most important part of the menu was the coffee, which the US Navy drank in vast amounts. As Samuel Eliot Morison said when discussing the need to protect the trade lanes to Brazil, "These commodities [from Brazil], with the possible exception of coffee, are essential to a nation engaging in modern warfare; and, although the United States Navy might win a war without coffee, it hopes never to be forced to make the experiment." A single aircraft carrier's 2,500 men could polish off a quarter-ton of the stuff on a single strike day.3 If brewed to the strength given in the 1945 USN cookbook, where coffee is the first item listed, that would be a thousand gallons, or 3.2 cups per man, about twice the normal consumption of the beverage. Other options sometimes available included tea, hot cocoa, and "bug juice", the term for various artificial fruit-flavored drinks made from powder. Besides producing something that is at least arguably a beverage, the powder is also quite effective as a cleaning agent.

A WWII-era mess in use aboard USS Fargo

And it wasn't just coffee that was consumed in massive quantities. A good illustration comes from Washington in 1941. Some of the supplies the battleship took aboard after about a week at sea with a crew of 1,500 were 2,400 lb lemons, 1,700 lb cucumber, 2,400 lb lettuce, 1,800 lb each of sweet potatoes, tomatoes and asparagus, 1,200 lb celery, 3,000 lb carrots, 3,800 lb oranges, 1,513 lb smoked hams, 19,971 lb of frozen beef, 4,070 lb veal sides, 507 lb head cheese, 1,040 lb flounder and 1,010 lb rhubarb. Of course, each of these had to be loaded aboard by a "bucket brigade" of sailors, and it wasn't uncommon for particular delicacies to be the subject of "midnight requisitions" by hungry crew. At one point, the problem grew so bad that Washington's captain had Marines posted to protect the food.

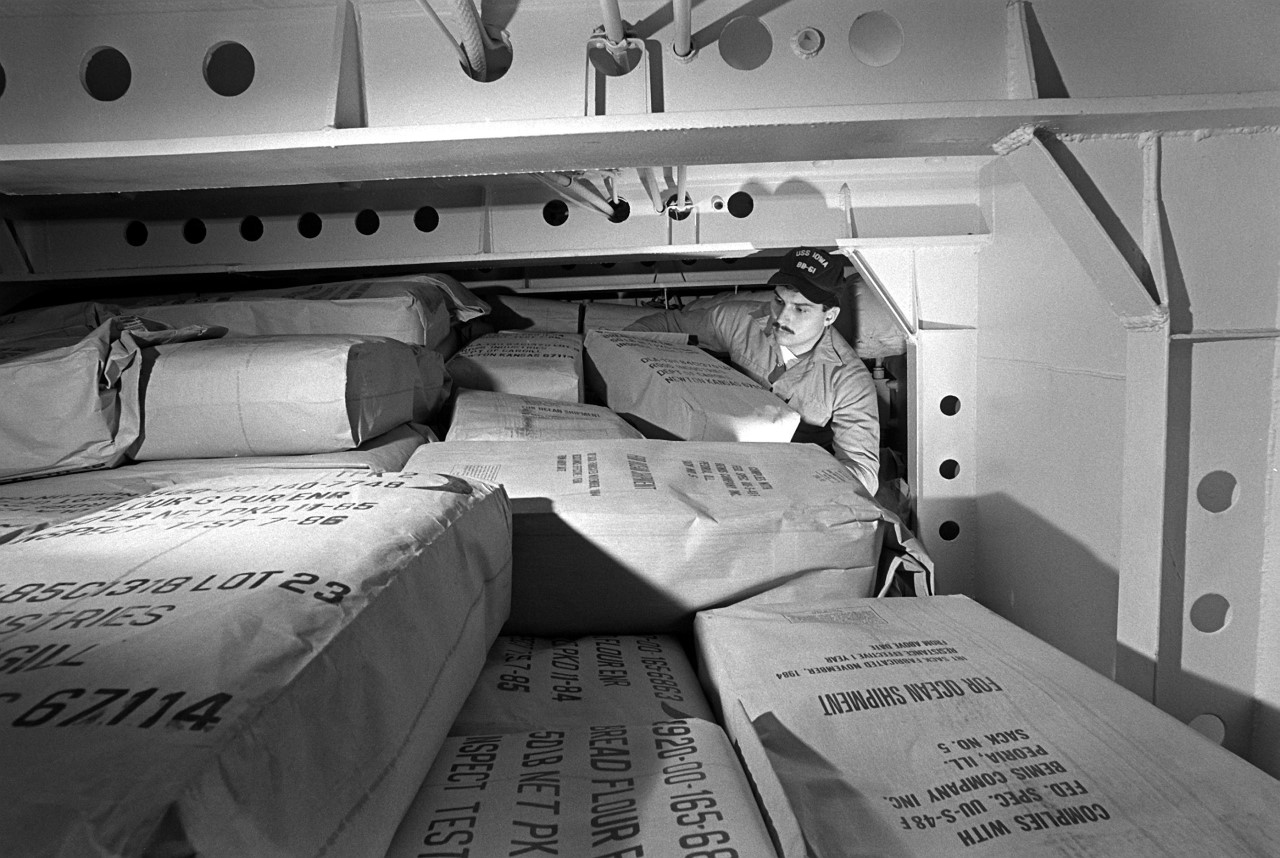

A cook checks Iowa's supplies in the 1980s

Iowa's crew in 1945, approximately 2,800 officers and men, consumed about 7 tons of food per day, at a cost of $1,600 in 1945 dollars, about $23,000 in 2020. 1.5 tons were fresh, 2 tons frozen, and 3.5 tons dry. The ship's storerooms could carry 100 tons of fruit and vegetables, 84 tons of frozen meat, and 650 tons of dry stores. In theory, this was enough to stay at sea for 119 days, and underway replenishment could extend this indefinitely. Another luxury was ice cream, with the soda fountain producing 9,600 gallons each month. The crew ate most of this, but some was transferred to other ships during underway replenishment, along with other supplies. In October 1944, Iowa passed out 45 tons of provisions, including 400 gallons of ice cream, and the ship's report noted that at no point did the ship turn down any request for fresh food.

Sailors line up for a meal aboard Iowa

Special events were honored with celebratory meals. Iowa's July 4th meal for 1945 cost $1.05 per man ($15 in 2020). The menu was quite impressive: "Cream of tomato soup; 240 gallons, Saltines; 240 lbs., Roast Young Tom Turkey; 2,849 lbs., Cranberry Sauce; 18 lbs., (dehydrated), Sage Dressing; 6 lbs., Cream whipped potatoes; 1,500 lbs., Buttered peas; 480 lbs., Hot Parker House Rolls; 4,500, Ripe Olives; 20 gallons, Sweet Pickles; 20 gallons, Cherry Pie; 1,200 lbs. of cherries / 2,800 pieces, Cigarettes; 2,800 packages, Mixed Candy; 2,800 packages, Ice Cream; 200 gallons, and Iced Lemonade; 640 gallons."4

Onions are loaded aboard Missouri

But while all of this was very nice in theory, it didn't always work so well in practice. The war in the Pacific strained the Navy's resources to the breaking point, and even with the help of Australia and New Zealand, it wasn't always possible to get fresh meat or produce to ships at the front. The submariners were always fed well, and the carrier groups generally were next on the priority list, but after that, it was often a monotonous diet of canned beans, spam, and other food that didn't require precious reefers to move forward. The situation improved later in the war, and by the time of Okinawa, the USN beat its targets for supplying fresh food so thoroughly that a number of dry stores ships spent months waiting to be unloaded, landing the Navy in trouble with the War Shipping Administration.

British sailors in the mess of a corvette

Not every navy was so lucky. The British believed that their sailors were tough, and that creature comforts would merely dull their edge. Some took this so far as to suggest removing equipment from lend-lease ships, although fortunately this didn't happen. Some British-built ships were better than others. Particularly bad were the Flower class corvettes, which had the mess decks all the way forward and the galley aft. Even if the riveted seams weren't leaking (a depressingly common occurrence), there was no way to get food forward without crossing the open deck, putting it at risk of being soaked in salt water or spilled. Later ships had a catwalk installed to keep the cooks out of the worst of the spray, but habitability onboard the Atlantic escorts was never very good.

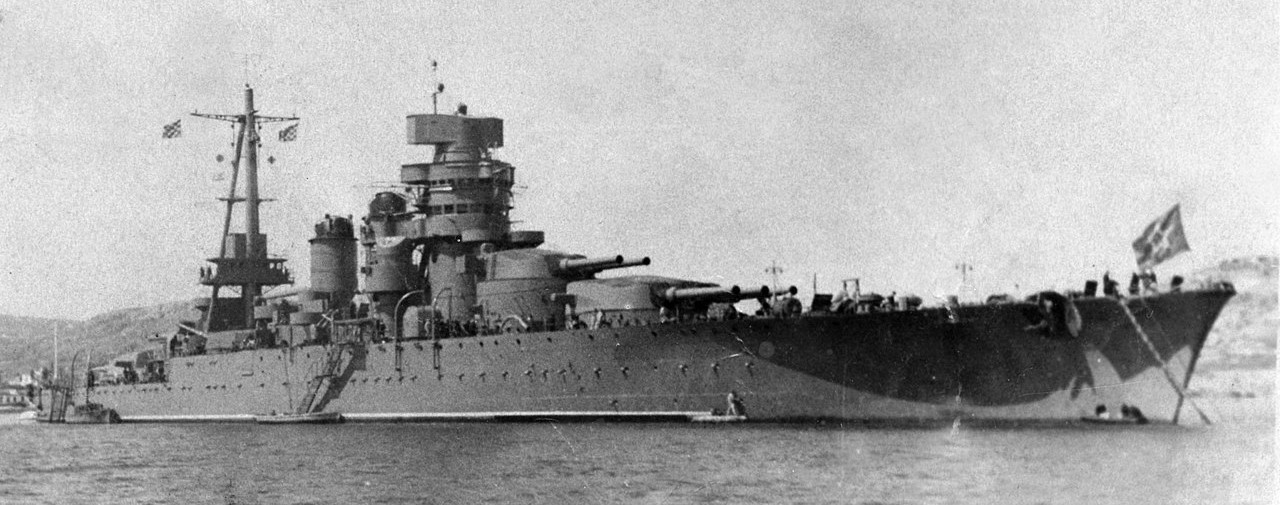

Novorossiysk, formerly Gulio Cesare

No other major navy followed the Americans in adopting cafetria messing, and all served versions of their national cuisine. Japanese sailors ate a diet based around rice and fish, with the rice available for off-duty sailors even when it wasn't mealtime. The Italian Regia Marina placed great emphasis on food quality, and its meals were prepared under the supervision of a dozen civilians recruited from restaurants ashore.5

British sailors on the battleship Rodney during WWII, the only picture I could find of sailors actually eating aboard a battleship

In the aftermath of WWII, cafeteria messing became universal worldwide. Food service continued to improve, particularly with the increased use of food prepared ashore, which reduces preparation work and improves the variety of food available at sea. Today, the USN uses the Navy Standard Core Menu, prepared by Natick Labs. This is a 21 or 28-day cycle of breakfast, lunch and dinner, with two entree options for each meal, as well as starch and vegetable options. Today's sailors demand better food than their forebearers, and the with retention an increasing problem, navies have generally been happy to oblige them.

1 This is an issue I am confused by. The traditional watch schedule was every 4 hours, so I'd expect the times to be 0730, 1130 and 1730. And I'm well aware that supper was 6 hours after dinner. The explanation is that it was in the middle of the dog watch. The 1600 to 2000 watch, known as the dog watch for reasons lost to the mists of history (and I'll flog anyone who makes that terrible pun), was split in half to give an odd number of watch cycles in a day and ensure that nobody got stuck with an undesirable watch long-term. ⇑

3 Morison Vol 7 page li, at least in my recent USNI edition. ⇑

4 Thanks to Dave Way for getting me the information on this, and for other helpful suggestions on this post. ⇑

5 This is hard to square with the tales (which I had heard but couldn't source when I went looking for this post) that the Soviets had trouble with the galleys on Gulio Cesare, which entered their service as Novorossiysk, because they were intended only for pasta on short voyages. I'd guess that the grain of truth there is the Soviets had trouble with the galley equipment, like so much else on Novorossiysk, but not because of inadequate facilities. It's remotely possible that there was a major doctrinal change from Cesare to the Littorio class, which I have most of my information on. The Littorios also had two months worth of food storage and onboard ovens, further evidence against it, for them at least. I recently got a book on the Cesare and her sisters, and it didn't even mention galley problems in Soviet service. ⇑

Comments

Minor correction, Para 4. "Bucked Brigade" should probably be "Bucket Brigade"

I forgot to send this one in for proofreading, and have found at least three typos since it went up. That was one of them, and it's already fixed.

That must have been an incredible jump in standards. It seems like the US followed the British but quickly overtook them, similar to everything else?

I'd have assumed thier motivation was retention back then too, but could they really have faced a recruiting shortage during the great depression?

Was surprised at the dishwashers and potato peelers, since that seems like perfect work to keep sailors busy. But since you still have to peel potatoes during combat ops (unlike holystoning the decks), it makes sense to automate.

Have you seen the fruit and veg storerooms on Iowa? Are they a sort of walk-in crisper drawer, like a Costco fruit room?

Keeping two months of fresh food stored in the Pacific must have been a huge challenge.

It's interesting that American submarines were fed well in World War 2, because I'd have expected submarines to be around the level of destroyers in the pecking order for food. Was it because submarines were too small to have decent galley space, and therefore were never that from a tender that had decent supplies?

Also, does this apply to other nations' submarines? Did the German U-boat crews eat well too?

Regarding your first footnote, I wouldn't be surprised if it was related to this: "There wasn’t enough space for everyone at once, but men dealt with this by spreading out service." Nominally dinner was at 1200 but does that mean food is available from 1200-200, or 1100-1300, or something even wider?

@echo

I'm not really sure what the motive was. Retention/recruitment probably played a part, as I'm sure did a belief that a happy, well-fed sailor was an effective sailor.

Re dishwashers and such, I'd guess that it was also a matter of space. The scullery on Iowa is maybe 15 feet on a side. Which is plenty for a couple of guys to work with the dishwasher. But if you have to wash dishes by hand, you're going to need more space for all the guys doing the job. Same for potato peelers. There's also the question of what your short pole is in terms of crew size. Is it set by combat, or by peacetime ops? I don't really know which it was on a typical warship design. And if it is combat, there's still the issue that keeping a sailor peeling potatoes means he isn't learning new skills or maintaining the ship.

I've been in one of the chilled store rooms, although it may have been a meat locker (it was only a few months after I started, so no pictures). It was basically a metal box, pretty unremarkable.

@quanticle

It was a morale thing. The attitude of USN leadership was that if you were going to agree to crawl into a metal can for a couple months (USN subs often took patrols from Hawaii to Japan) they were going to do what they could for morale, and good food doesn't take up much more room than bad food. Can't say exactly what other nations did, but I wouldn't be surprised if it was similar. Obviously there were challenges, as most subs went to sea with a layer of cans on the floor of most passages, and the fresh/frozen stuff ran out before the cans did. But on the whole, the submarine force ate pretty well.

@David W

That came from the 1943 Bluejacket's Manual. Those times were pretty clearly marked as the start of the meal. I think the mealtime usually lasted an hour or an hour and a half.

Interesting in how the picture (2nd from top) of the sailors above decks on the NJ how the guy 4th from the left looks as if he is checking his cell phone. One of those time portal events.

Hmm, I found a possible answer by google "If a MIC will miss a meal due to watchstanding, they should be temporarily relieved by a supernumerary to attend chow" from https://www.usna.edu/NAPS/_files/documents/NAPS-Instructions/NAPSINST%201601%20-%20Watchstanding%20Instruction%20.pdf It's a modern reference, but it makes sense. If you're on watch, you're not allowed to leave without a substitute - but that's not the same as being chained to your station. Presumably there were similar allowances for hitting the head or grabbing some water.

Quite possible that was the general approach. Maybe just a matter of expectations - if you're on watch, grab your food and bolt it down and get back to your station so that the next guy can be relieved. If you're off watch, take your time and enjoy yourself.

Re. quant & bean

Am I misremembering, or did the German u-boat-tender-u-boats also have a bakery? If so, it's a sign of the value they placed on decent food. I know they at least delivered fruit and veg.

(Now I'm curious if our modern nuclear subs have them too. They certainly have enough power for it!)

@David W

That specific instruction is for midshipman candidates at the Naval Academy Preparatory School. The watchstanders there are basically sentry/security, and they're definitely not running a ship. Typical practice in cases like that is to have one or two guys per unit (platoon/company) on watch, and it's obviously a lot easier to find a replacement in that case than it is when you're dealing with a full watch on a ship at sea. I don't understand why the USN schedule doesn't start dinner and supper 30 minutes earlier and give the guys about to go on watch a chance to eat.

@echo

They have ovens, yes. I think US boats did during WWII, and HNSA has a submarine cookbook which should be able to confirm. (I don't feel like sorting through photos right now.) There are several articles you can find easily online about submarine cooking today.

This actually is in fact how it's done today; Early Chow for Watch Reliefs is held 30 min before the start of the normal meal. Theoretically, someone is supposed to check to make sure that the guys in the mess line are actually going on watch, but I don't think I've ever seen it done that way in practice.

I never understood how dogging the watch was actually supposed to work, either; it was an artifact of before my time, and seemed mysterious.

Interesting. But I couldn't find any trace of such practices in my WWII Bluejacket's manual, and I didn't feel like buying a bunch of books to try to run this down.

There's no mystery about how it's supposed to work. If you just went with straight 4-hour watches, you'd end up with the same people on midwatch for long periods. That's unpleasant, so you split one watch in half to give an odd number each day. The mystery is why it's called the dog watch.

Also, they don't do it any more? I find that weird.

@echo

According to this article from the L.A. Times, submarine food is still pretty good. They mention fresh baked donuts and cakes, so I assume that it's still standard practice to have baking facilities aboard subs.

Since we've established that submarines have the best food, I wonder which ships (in the current USN) have the worst food?

My guess is going to something like a LHD. I have a friend who served a tour of duty aboard one, and he noted when the full complement of sailors and Marines were aboard, the galley had to feed nearly 3000 people. In that situation quantity over quality is emphasized.

It'd make sense to bake on a sub, where space is at a premium.

Otherwise you're carrying around a load of air inside your leavened foods for no reason.

I suppose the respiration rate of yeast isn't high enough to overwhelm the scrubbers or anything.

Bonus photo: baking subs on a sub

https://nara.getarchive.net/media/mess-specialist-third-class-raymond-shields-brushes-butter-on-to-freshly-baked-3109af

@quanticle

Cyclone-class PCs. IIRC, the galley is a hotplate and maybe a microwave.

Re LHDs, I've actually eaten aboard one, and the food was pretty good. Yes, there was just the ship's crew and a few Marines onboard at the time, but it's not like a full load of Marines isn't something the designers knew was coming. All you have to do is stock some extra cooks and extra space. I actually got to talk to the warrant officer in charge of food service a few days later. He definitely seemed competent, but he'd also been a Navy cook for ages.

Also, note that these days everyone gets the same meal plans with the same ingredients. I'd guess food quality varies more with the skill of the kitchen staff than anything else these days.

"Small shift that follows the big real shifts around" would be my guess. Another term with what I believe have a similar etymology is "sun dogs", which is an atmospheric phenomenon where two smaller suns appear to follow the real one around the sky.

Has fresh fish ever played into naval rations in a significant way? Quick searching finds plenty of fishing in the modern navy, but it sounds like mostly recreational (not that they don't eat the catch).

Then again, baking means you're carrying around an oven and all auxiliaries, and someone has to bake bread regularly instead of doing something else. I'd guess it's simply a matter of making life as good as possible for those sailors who actually volunteer to get sunk.

Couldn't "dog watch", like many English maritime- and sailing-related words, be borrowed from Dutch dag, meaning day? As in, it's the end-of-day watch, or it's split in half, which only happens once a day, or..?

How then do they solve the stand-the-same-watch-for-6-months problem?

Hot cocoa, I hope, not hot coca! But, especially purified, that would have led to the most exciting day of operations ever....

@ADA

No. Catching fish simply isn't reliable enough to play a major part in anyone's rations, and never has been.

@Alex

Might be from Dutch. There's apparently debate in etymological circles (those that care, anyway) about this.

As for bread, ovens aren't that big, and it's a major quality of life improvement. And I'm not sure how much extra manpower it actually needs relative to other tasks.

@Goose of Doom

My bad. Fixed.

Nobody can agree where the word 'sundog' came from either. 'Dog' is a mystery too.

Can confirm you can make bread in a small oven. (source: only the top oven/grill of my double oven works) I'd guesstimate the breakeven point to be well under 30 half-kilo loaves. I.e. 15kg flour + an oven takes up less space than 30 loaves. Baking also scales up well, since you can use things like automatic mixers.

@bean

Is this a series of posts you just happen to be getting around to or is this your equivalent of reading interior design magazines and pinterest moodboards, now that you own a house? Putting hammocks in a dining room would certainly free up a lot of space for bookshelves.

Hmm. I must speak to Lord Nelson about that.

More seriously, these have been in work for a while. A check of the history shows that this post was first created on May 30th, which was before we put a contract on the house. It just took a while to gel, as they fairly often do.

@Lambert

Please don't tempt him. It would give his wife just cause to murder us.

..In 1988 I had the pleasure of having lunch aboard NORFOLK (SSN-714). Two things still stand out - the food was, of course, amazing but apparently it's good only as long as it holds out, then "It's three bean salad twice a day." The other thing was the coffee; before or since the best I've ever had. I said so and the response was, "Of course it is - nuclear powered coffeemaker."

HNSA has a book on submarine cuisine here, which is good enough that it's likely to get its own post. I thought it was just a WWII cookbook, but it's considerably more than that. As for why I didn't check it earlier, I wasn't really writing about submarine food. But it's good enough that I suspect Naval Rations - Submarines will make an appearance at some point.

ADA, Bean probably could have added fishing, sea-bird-trapping, and rat-baiting to the first post in the series, but the hardtack and weevils were bad enough.

It's not fishing, but I seem to remember naval vessels used to buy directly from fishing trawlers when they had the chance?

Also re. baking, I don't know what they put into modern bread to stop it going hard, but after about four days my loaves need a bit of rehydrating and toasting to be any good.

So it was probably more of a freshness thing than space-saving.

Buying from trawlers was pretty common, particularly during the age of sail. In fact, the British used to buy catches from French trawlers, which was also a good way to pick up rumors. But I don't think that's happened much in the last century or so.

My father made it to CWO4 in the USNR. He only went to sea once, on an Italian destroyer (NATO exercise, I assume. He was doing his 2 weeks in Sigonella). He brought back from that trip a sea story about how the captain bought the entire catch off a trawler for dinner one night.

(Early eighties)

I think I may have asked you this in person but what promoted the change from hammocks to bunks?

FWIW, OED thinks that "dog watch" etymologically was a transference from Dutch hondenwacht (hound watch) or German Hundewache, and both were "probably so called because on land this was the period when the household slept and only the dog kept guard."