On April 9th, 1940, Hitler unleashed his military machine on Norway, breaking that country's neutrality and overwhelming the unprepared defenders at cities including Oslo, Kristiansand, Stavangar, Bergen and Trondheim using troops carried aboard warships. The British had their fleet in the North Sea, and Renown had fought Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off the mouth of the fjord leading into Narvik, but they had been unable to intervene and prevent the Germans from running 10 destroyers into that strategic town and securing it with minimal struggle.

German destroyers anchored in Narvik

The scale of all this was unclear to the British offshore, even as a force under Admiral William Whitworth assembled off Narvik during the 9th. While most of Home Fleet was well to the south, he had not only Renown, but also her sister Repulse, cruiser Penelope and a number of destroyers. Among them was 2nd Destroyer Flotilla under Bernard Warburton-Lee, who at noon received orders from the Admiralty indicating that the Germans had sent a ship to Narvik, and ordering him to take his ships in and see what was going on. If possible, he was to retake Narvik, or at the very least capture the mythical batteries protecting the city. Warburton-Lee complied, bringing with him destroyers Hardy, Hotspur, Hunter, Hostile and Havock, although more ships were available and probably would have been dispatched if the Admiralty had contacted Whitworth instead of going directly to Warburton-Lee. The casual tone of the order was baffling given the ongoing German invasion, and it left the men on the spot with the impression that the Admiralty knew far more than they did. This was often the case, but here it would prove tragically wrong.

Bernard Warburton-Lee

Warburton-Lee's destroyers reached the pilot station at Tranoy at 1600 on the afternoon of the 9th, and sent a party ashore asking for information on any German ships that had passed. They were told that six destroyers had passed, but dismissed this information, and Warburton-Lee decided to follow his orders and attack with the force he had at dawn the next day. His ships headed up the fjord towards Narvik in a driving snowstorm, barely able to make out the ships ahead of them. Somehow, the navigators found their way through, and the bad weather hid them from the U-boats standing sentry. Warburton-Lee dispatched Hotspur and Hostile to deal with the coastal batteries, and took his other three destroyers into Narvik harbor at 0430, only 10 minutes or so after German destroyer Roeder had left her picket station without being replaced. It is not clear exactly how this was allowed to happen, but it meant that the Germans had no inkling of the British presence until Hardy opened fire. She had already fired her torpedoes, and while most of them missed, one struck the German flagship, Heidkamp, blowing off most of her stern and killing Kommodore Friedrich Bonte, the German commander. The ship was only saved from sinking by lashing her to a nearby cargo ship, and she would capsize the next day. The Germans raced to return fire while Hunter and Havock entered the fray, each firing their torpedoes into the mass of shipping deep in the harbor. Several merchant ships were hit, and Schmitt took two torpedo hits, breaking in half and sinking almost immediately. The shock from the second hit also seized the engines on the nearby Kunne, which had been refueling from a tanker when the British arrived. The disabled destroyer drifted onto the wreck of Schmitt, taking her out of the fight. Ludemann, which had also been refueling, took several hits from Havock, one of which severed steering control and forced the magazines to be flooded.

Ships burn in Narvik harbor after the British attack

Roeder, which had anchored only moments before, tried to fight back, launching a full spread of torpedoes blind towards the harbor entrance. Some passed underneath the British destroyers, which drew less water than their German counterparts, but none hit. In the face of intensifying fire, the three British destroyers pulled back, while Hotspur and Hostile, having found no batteries, entered the fray. Hostile quickly engaged Roeder, pumping at least 5 4.7" shells into her and leaving her a burning wreck, limping to the pier dragging the anchor she no longer had power to raise. Warburton-Lee withdrew to consult with his staff. They believed that they faced six destroyers, and thought they had accounted for at least three. In reality, they had badly damaged all five in Narvik harbor, but five more waited outside in two different groups, alerted by a message from Ludemann to the presence of the British ships.

The first group of three ships was quite close in and arrived shortly, prompting Warburton-Lee to withdraw down the fjord, laying a smokescreen to cover his retreat. The Germans, extremely low on fuel and uncertain of the survival of their tanker given the holocaust in the harbor, didn't pursue very far. But the second pair, further down the fjord, found themselves directly across the bow of the British force, in the perfect position to spring a trap. Warburton-Lee, not realizing that the other group had broken off thanks to his own smokescreens, turned to bring his aft guns to bear before Thiele began to pump shells into Hardy. At least a dozen found the mark, smashing the superstructure, putting the boilers out of action and mortally wounding Warburton-Lee, who would later be awarded the Victoria Cross. The surviving officers ran the dying destroyer aground, and the crew abandoned ship ashore.

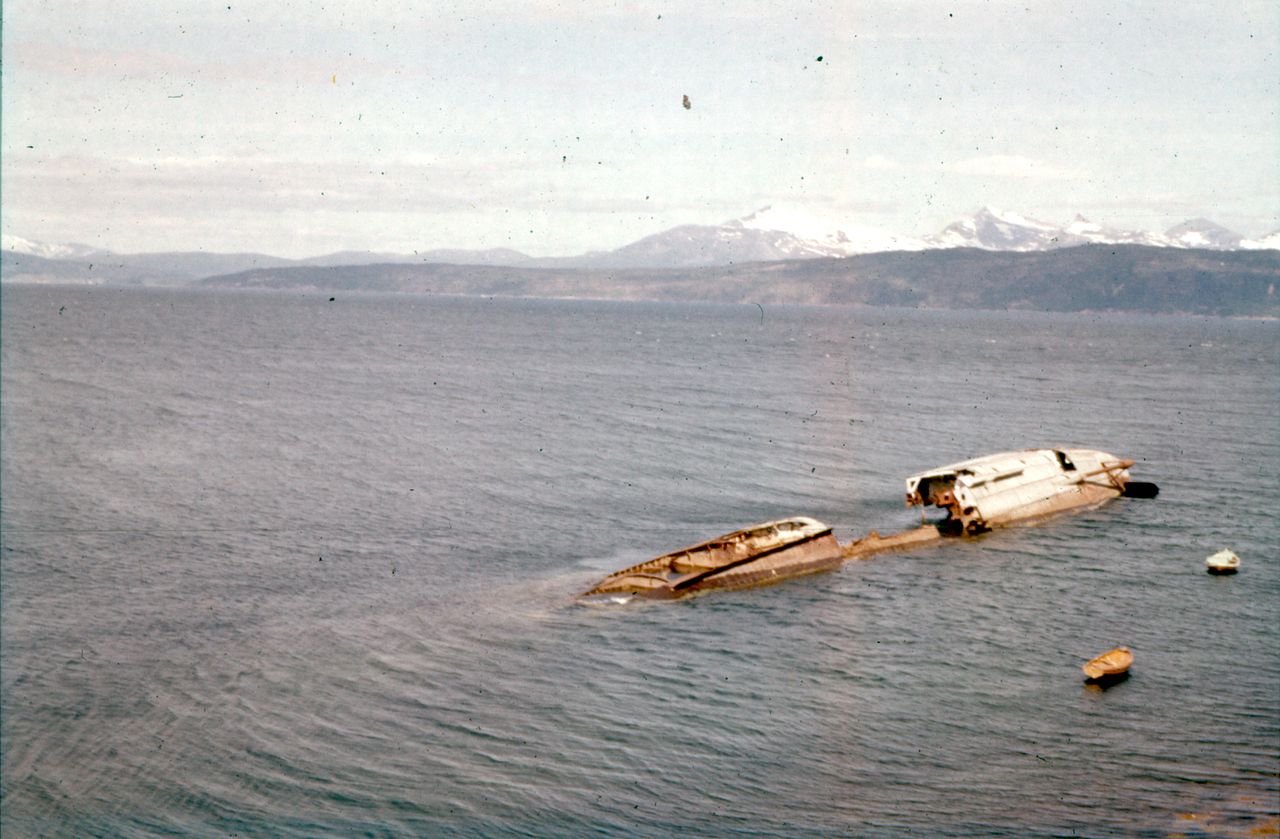

The wreck of Hardy postwar

Havock, now the lead ship, took several hits and broke out of line in the confusion, although her injuries were far less serious than those of Hardy. That left Hunter in front, and she began to score hits on Thiele, but soon became an inferno under fire from the two German ships. Her engines failed, and Hotspur, out of control after a pair of hits, rammed her from behind. The two ships remained locked together under fire from the Germans for long minutes as Hostile and Havock headed down the fjord. Hotspur's Captain eventually managed to restore control and free his ship, while the crew held the Germans at range with their operational guns. Hunter capsized as Hostile and Havock returned, laying smokescreens as the damaged Hotspur withdrew. The Germans let them go, a particular relief to the badly-damaged Thiele. As they cleared the mouth of the Ofotfjorden, they encountered the German supply ship Rauenfels, carrying cargo bound for Narvik. Her crew ran her aground, and two shells from Havock set off the ammunition onboard, destroying the German vessel utterly.

Narvik harbor after the British visit

On paper, the battle was a draw, with both sides down two destroyers. In practice, a a significant portion of the German destroyer fleet was stuck in Narvik harbor, low on fuel and ammo and with most of the ships having some degree of damage. An attempt by the healthy ships to join Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on their return to Germany on the evening of the 10th was thwarted by the blockade the British had slapped over Narvik. Meanwhile, the RN's losses were fairly minor relative to their total destroyer force, and Hotspur was dispatched to nearby Skjelfjord, where a temporary repair and supply base was established using a captured German freighter, soon supplemented by a Norwegian salvage ship and a number of local fishermen, used to repairing their craft with whatever came to hand. A plan to attack Narvik again on the 12th had to be abandoned when cruiser Penelope ran aground on the 11th and had to be towed off with several of her engineering spaces flooded. Instead, the British launched an air attack using Swordfish from Furious, eight of which bombed the Germans that afternoon. Unfortunately, the weather was not great, and none of their bombs hit, while two of the planes were shot down by AA fire, their crews rescued by the British. But that was only a taste of what was to come, for on the 13th the RN would return to the Ofotfjorden. We'll pick up the story there next time.

Comments

Possibly the most successful deception operation of WWII? So far it has deceived both the Germans and the British, and given what we know of the Norwegian government at the time I wouldn't be surprised to find that Nygaardsvold believed in them.

After reading so much about battleship combat, it's almost surreal to hear about ships being destroyed by a handful of sub-5" shells. (Did anyone ever try to design a fastish ship armored against secondaries, for attacks like this or pushing against destroyer screens?)

That sounds a lot like a cruiser.

@Bernd: Destroyers getting tougher (though possibly due to increased size rather than any explicit protection) was at least plausibly why secondary guns got bigger over time.

@Rolf

Yes, although I'm not sure who would have carried it out.

@Bernd

As ike says, that's not a bad description of some light cruisers, particularly in the years around WWI.

I guess even for a rare coastal attack scenario like this, armor couldn't be expected to do much. It wouldn't help against torpedoes, you couldn't armor the upper works enough to prevent a mission-kill, or have enough tonnage for redundancy in soft components. And armoring against 5" still leaves you just as vulnerable as an unarmored ship to a cruiser's 6-8" guns.

So the only stable equilibrium is a basically unarmored ship with good damage control and a bit of anti-frag over your machinery spaces and magazines, like the Fletchers, so there's more chance to save the ship or at least get everyone off. Or scaling up to a cruiser that you wouldn't want to throw into this kind of knife fight anyway.

Man, being a destroyer man was a rough job.

@Bernd: When Bean gets around to writing Part 12, it will be revealed that throwing a large armored warship into this sort of knife fight is sometimes a pretty good move. And in the general case, the ideal ship for killing destroyers is I think a light cruiser. But they're quite a bit more expensive, and not as good at ASW and other screening/escort duties.

From my memory of a book I read last year, so take with a grain of salt, it was a combined effort by the many short-lived Norwegian governments of the early nineteen twenties; there are five governments formed between 1920 and 1924 inclusive. One of them, drawing on the experience of needing to be a heavily armed neutral during the Great War, created an ambitious coastal defense plan with extensive engineering drawings for those forts; the others universally shoved the funding ahead to "next year" and then "next decade". But the plans remained right there on the books in Oslo, much more accessible to Great Power spies than the actual un-improved mountains in distant Arctic backwater Narvik.

Equal losses is a strategic victory for the British, who have a lot more ships to lose than the Germans.

Wow what a battle! Love reading about this whole campaign - one I wasn't aware of - and looking forward to the next part!