April of 1940 began with the war in Europe at a stalemate, as both sides stared at each other across the Franco-German border. The first action of the war in the West was the German invasion of Norway, in the hopes of securing iron ore supplies and opening a new flank on the war at sea, outside the British blockade. The Norwegians largely expected their neutrality to hold, and while the forces available generally fought back, they were confused and aimless, leading to a number of German victories across the southern half of the country.

A gun at Kvarven Fortress

One of the German targets was Bergen, the second-largest city in the country.1 It was the headquarters of Admiral Carsten Tank-Nielsen, who was responsible for the section of coast stretching from Stavanger to Trondheim, and who, unusually among Norwegian senior officers, took the threat of attack seriously. On April 8th, he ordered his ships to full readiness, although this wasn't communicated clearly to the coastal defenses that guarded Bergen. As was the case elsewhere in Norway, these dated back to the turn of the century, and hadn't really been modernized. The main defense of the city rested with Kvarven Fort, armed with a trio each of 21 cm guns and 24 cm howitzers. A second fort at Hellen had another three 21 cm guns, and various outer forts had lighter guns, although they were considered useless without their protective minefields, which couldn't be laid without authorization from Oslo. Another heavy battery was completely unmanned, and a torpedo battery similar to the one that guarded the entrance to Oslo was inexplicably overlooked in the preparations.

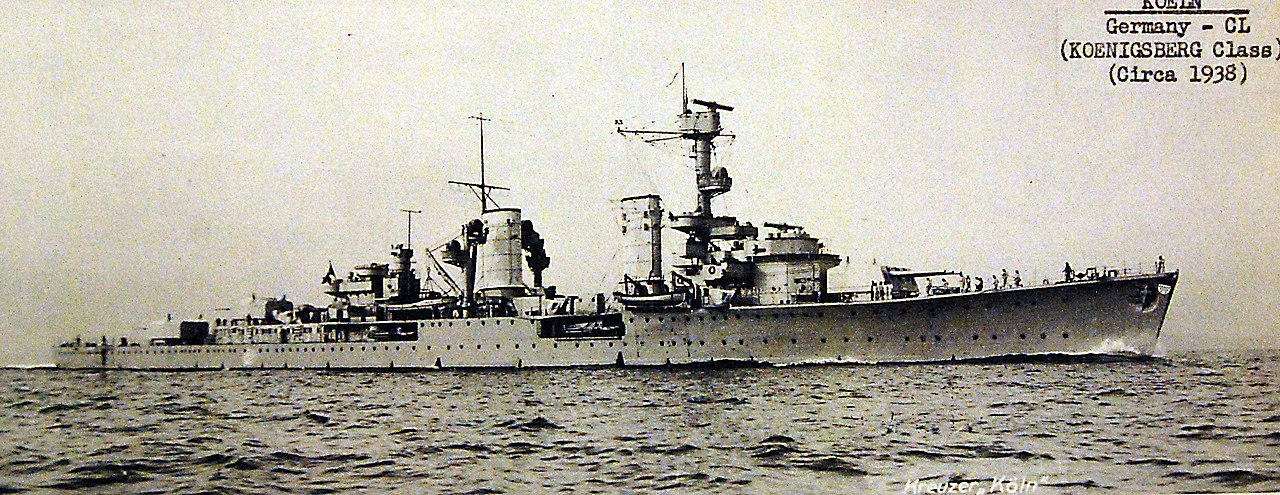

The German force approaching Bergen was led by light cruisers Konigsberg and Koln, who had orders to identify themselves as HMS Calcutta and HMS Cairo if challenged. They were joined by escort Bremse, torpedo boats Leopard and Wolf, tender Carl Peters, a flotilla of S-boats and a pair of trawlers. They were first detected just after 0100 by one of the small ships patrolling the entrances to Bergen, who sent up flares and challenged the ships. Koln replied claiming to be British, but the Norwegians misread the reply as the German for "Remain calm", and reported them as German vessels. Tank-Nielsen, who was receiving no help from Oslo despite the presence of German vessels in the Oslofjord, gave orders for his forces to attack the intruders. Unfortunately, as part of the preparations, the public electrical grid was shut down to enforce a blackout, which also cut power to Kvarven and Hellen, forcing them to load their guns manually and denying them searchlight support.

Torpedo boat Sael

The first action in defense of Bergen was undertaken by the antique torpedo boat Storm, of a similar age to the fortresses around her, around 0220. She fired a single torpedo, probably at Carl Peters, and missed, although two of the S-boats saw the launch and gave chase as Storm hastily withdrew into the shadows of the fjord. Thanks to extreme measures, such as the chief engineer sitting on the safety valve, the Norwegian vessel managed to get away, but she was out of the fight. Farther up the channel, minelayer Tyr had begun her work, but only seven mines were in the water before the German warships were on top of her and forced her to withdraw. Even the mines that had been laid were useless, as their safety devices took a while to dissolve in seawater. The nearby fort opened fire with its 6.5 cm guns, but the Germans interpreted its fire as warning shots and kept going. Another torpedo boat, Sael, blundered into the midst of the Germans, and her crew was too busy avoiding a collision to shoot, while the invaders were still trying to avoid a fight.

At 0340, the German force had reached the point where they were to turn east for the run into Bergen, exposing themselves to the fire of the forts at Kvarven and Hellen. Konigsberg was detached with three of the S-boats to transfer troops, while the other ships proceeded ahead. They rounded the headland into view of Kvarven around 0400, and the battery opened fire almost immediately. It was located about 150 m up a cliff, giving it a commanding field of fire, but that field was only 3.5 km deep, giving maybe 10 minutes to shoot before the ships were past. Haze meant the gunners had trouble finding their targets, and while shells fell around the Germans, the batteries scored no hits on the first three ships through, Wolf, Leopard and Koln. The Germans thought that the fire was merely to save their honor, and reported that they felt every shot should have hit. They then shifted fire to Bremse, putting a 21 cm shell through her bow, although the fuze failed to function. Carl Peters turned back at the sight of the shells falling around Bremse.

The (daytime) view down the fjord from Kvarven. The bridge was built 50 years after the action described here.

Hellen was next up, with a better field of fire, although the long range and mist meant that the fire from that fort was ineffective, and two of the three guns suffered technical problems. They were also concerned about a torpedo boat reported operating nearby, but this boat, the Brand, passed up a chance to attack a few minutes later, claiming it was too light to do so safely. A few minutes later, the Germans entered Bergen harbor, and Koln, Leopard and Wolf began to unload their troops, quickly securing the eastern side of the harbor.

By this point, Konigsburg had finished transferring troops, and turned to follow the other ships towards Bergen. She came into view from Kvarven around 0440, and the fort opened fire, taking advantage of the improved visibility to land the first salvo from the 21 cm guns close aboard. The second managed to land two hits on the German cruiser, although both shells appears to have broken up instead of detonating. One hit amidships, throwing fragments into a boiler room and severing steam lines and electrical cables. The second was further forward, destroying a 37 mm AA gun and doing damage throughout the bow. Konigsburg returned fire, disabling one of the guns, while the other two were taken out of action by technical problems. The 24 cm guns never fired, despite orders to do so, and the damaged cruiser managed to reach Bergen harbor.

Koln

Confusion kept Hellen silent until 0600, when orders finally came to resume fire, and shells began falling close around the anchored Koln. Both German cruisers returned fire, but their shells were low, and the battery was silenced by air attacks from six He111 bombers that had been overhead for the previous hour. At about the same time, Kvarven fell to Germans landed from the S-boats. The gunners had held them off for an hour or so, but promised infantry reinforcements from the alert battalion nearby never arrived, and a three-pronged infantry assault, bolstered by gunfire support and bombing, left them in a hopeless position. Hellen surrendered to advancing infantry at 0735, leaving the Germans in complete control of Bergen. The Norwegians had lost two prisoners killed by friendly fire at Kvarven and six dead at Hellen, while the Germans suffered only four killed in the taking of Kvarven, along with various wounded on both sides.

The British became aware of the situation in Bergen almost immediately thanks to various liaisons in the city, many of whom managed to escape capture and aid in the ongoing fight. Two air raids were launched by Wellington and Hampden bombers, although none of them scored any hits on the German ships. Koln, Wolf and Leopard tried to escape back to sea that evening, but the air raids and reports of British ships off the coast led them to take shelter in the fjords south of Bergen and wait for the next day. Early on the 10th, a Norwegian floatplane on patrol saw them and mistook them for some of his own Navy's ship, landing nearby to talk to them. He realized his error just in time, and took off again pursued by 20 mm fire from the Germans. That night, the ships departed, reaching Wilhelmshaven unmolested on the 11th.

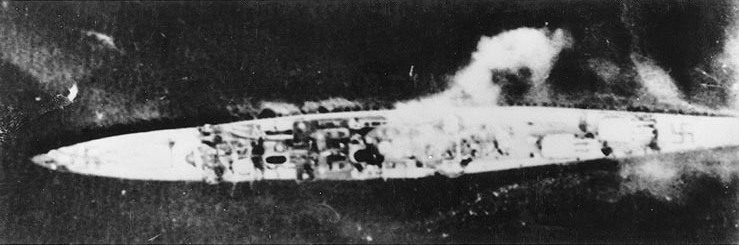

Konigsberg under air attack

Konigsburg wasn't so lucky. She had been left behind due to the damage she had taken, and after a recon flight confirmed the ineffectiveness of the early bombing raids, she was to be the target of a raid by the Fleet Air Arm. The Blackburn Skuas of 800 and 803 Squadrons were based in the Orkneys to provide fighter cover to Scapa Flow, but they had been built as multirole fighters/dive bombers, and they just barely had the range to reach Bergen. In the early hours of the 10th, 16 Skuas took off, each carrying a 500 lb semi-armor piercing bomb. All of the aircraft reached Bergen, and while they found only one of the two cruisers they expected, only a few guns could bear on them, and no fighters molested their dives. One Skua went down shortly after clearing the Bergen area, and two others limped back to Orkney with damage, but they had done their work well. Six bombs had either hit or fallen close enough to do damage, leaving the cruiser a powerless, burning wreck, taking on water in all four boiler rooms. Two and a half hours after the attack, she capsized pierside, the first major warship ever sunk by air attack.

Nor was Bergen the only place the British were active. Before we look at the next German object, Trondheim, it's time to examine what was going on out at sea.

1 Or the largest, if we use Rolf Andreassen's description of Oslo as "five or six suburbs in a trenchcoat". ⇑

Comments

I have to say, stories like this really, really demonstrate the importance of surprise in warfare. The German plan was insanely reckless in a lot of ways, but it worked, because of surprise.

This sounds like the kind of mistake that would be very easy to make if you knew they were lying and didn't want to report "true but inaccurate" information up the chain of command...

No, it was a genuine mistake. She was identifying herself as HMS Cairo, but for some reason it was read as "Sei Ruhig" ("remain calm" in German). The Norwegians in general were bad at ship recognition (witness the French flag mishap at Kristiansand).

This entire invasion reads as though it was scripted by Groucho Marx.

It provides a good background as to why the Germans assumed they'd be able to roll over the Russians in a couple of months. If your experience up till now has been that your enemies are mostly sitting around with confused looks on their faces while you waltz in and take what you want, then you're going to be overconfident.

The German force approaching Bergen was led by light cruisers Konigsberg and Koln, who had orders to identify themselves as HMS Calcutta and HMS Cairo if challenged.

I am under the impression that doing this in ground combat is grounds for being shot as a spy. Is this

a) Not the case at sea. You can fake your ID all you want? b) Is the case in 1940, because Ooops, we forgot to tell the navy boys about the changes in the rules over the past few centuries. But it's been updated now. c) Absolutely was a war crime but the Germans didn't care?

This is actually one of the major reasons I started writing this series. Not as a background to Russia, but as a background to Sea Lion.

Re false identification, at least in the Age of Sail, it was legal to fly false colors, so long as you had the correct ones up by the time the shooting started. I'd assume this was an extension of that, but my book on maritime law doesn't say.

I vaguely recall similar shenanigans being used to good effect in modern naval exercises. So, I think it lives on, at least in part.

My home town. If you stand next to the gun in the first image and face away from the bridge in the second, you can see my parents' house.

Ah yes, but Germany and Norway weren't technically at war, the Germans were there to protect Norwegian independence... No, seriously, I think it comes under the "false flag ok until you start shooting" bit.

I read somewhere or other that they held out for roughly as long as they had ammunition for their one machine gun. This is another one of the many facepalm moments of the invasion; I've hiked up to the gun emplacements many times (my friends and I used to play in the bunkers under the guns, now open to the air) and seen the fighting positions carved into the bedrock. It should not be possible to take that place by infantry assault. I suppose it would have surrendered eventually to air bombardment, as happened at Kristiansand; there's no overhead protection to speak of. But never mind a battalion; a single company, reasonably supplied with ammunition, would have held against any infantry assault you like, three-pronged or not.

@bean

Regarding ***-**** I think the natural antecedents are found in the Schleswig wars. The allies were able to pull off amphibious landings against the Danes despite crushing naval inferiority. Replace 'field artillery' with 'aircraft' and you basically have the plan for ***-****.

Interesting. Obviously, something like that doesn't just have one antecedent, and it's very possible that both the Schleswig War and Norway were part of a pattern where Germany systematically underestimated the difficulty of amphibious warfare. I definitely don't think lessons from almost a century earlier would alone lead them do things that anyone familiar with WWII amphibious operations immediately sees as lunacy.

Well, if you were at the war collage in the'20s, teaching amphibious warfare, what case studies would you use? Probably Schleswig, some WWI stuff in the Baltic, and a lot of river crossings, if you didn't want to lean too heavily of foreign sources.

Actually, thinking of amphibious warfare as a slightly bigger river crossing explains a lot.

As I understand it (mostly from the histories I have read concerning the Battle of the Bulge), wearing the "wrong uniform" is a "legitimate" ruse de guerre as long as you don't actually engage in combat in the wrong uniform. This was an important legal point for the prosecution after the war of some of the German officers who participated in the infiltration teams that were used in the BotB.

As a practical matter, if you were caught in the wrong uniform, you'd likely be shot out of hand regardless of the legality.

Well, if you were at the war collage in the'20s, teaching amphibious warfare, what case studies would you use?

Gallipoli springs to mind.

On the subject of naval perfidy: you're definitely not supposed to do it, it's definitely illegal, and the penalty is uh...unspecified and as always with war crimes, up to your discretion if you win. So win and you're good!

In today's world, there's a diminishing return in doing obvious stuff to fool visual identification like flying a false flag for fairly reasons ("Hey, that DDG-51 class ship is flying a Russian flag, I guess it must be a Russkie"). Deceptive lighting is something that is practiced and still a tool that gets talked about a lot; I always thought it was kind of dumb in a world where every EO/IR technology has become incredibly cheap and widespread (like, uh, you think those People's Maritime Militia fishing boats aren't going to have pretty decent NVGs onboard, guys?).

Somewhat interestingly, very clearly not illegal is things to fool electronic identification (eg transmitting false AIS signals, restricting what radars you transmit to those only used on civilian vessels). I'm not sure why those are legal and not frowned upon, because there are certainly downsides and real-world costs to doing so (as an example, I'm fairly certain MH17 got shot down because the Ukrainians had been lousing troop transports into the airport at Mariupol or wherever, and the rebels/Russians didn't bother with target deconfliction). But no one really talks about it.