How destructive are nuclear weapons really? This is a question that seems to be asked far less often than it should be, and is rarely discussed in a non-alarmist way. In fact, nuclear weapons are not a threat to humankind, and we can expect a vast majority of people to live through a nuclear war. None of this is to say that nuclear war wouldn't be a big deal, or a terrible humanitarian catastrophe, but it wouldn't be enough to wipe out civilization, much less the human race or all life on Earth.

We should probably start with a look at the state of the global stockpile, because it's fallen dramatically in the last 30 years. After peaking at around 70,000 warheads in the mid-80s, it's fallen to only 12,700 according to the Federation of American Scientists. The majority of these are in the reserve stockpiles of the United States and Russia, which are there in case the current arms-control regime fails, and would take time to deploy. Denying the other side this time is undoubtedly a major objective of both nation's nuclear forces, so in practice, we should instead look at deployed warheads. Arms-control treaties limit both nations to 1,550 deployed warheads, although FAS estimates 1,588 for Russia and 1,644 for the US, probably due to slight differences in definitions. Worth adding to this are the Chinese (380 warheads), the French (280) and British (120), for a global total that we can round to 4,000 warheads for simplicity.1 Some of these won't work, or will get shot down, but we can assume that other nations and the surviving stockpile weapons will bring the total back up. Note that this is a worst-case all-out nuclear war, and there are potential off-ramps short of it even if there was, say, a tactical nuclear exchange in Eastern Europe, although they aren't certain.

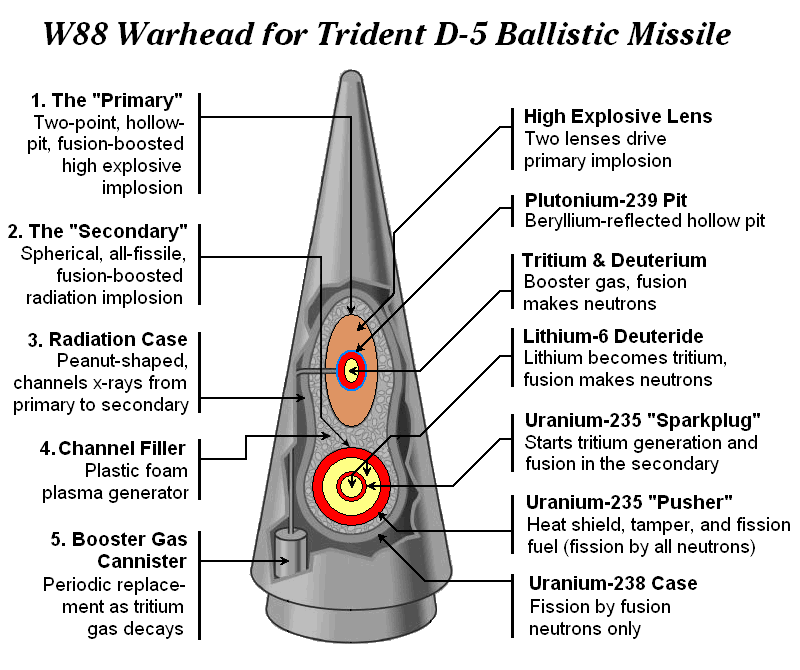

The obvious next question is what each of those bombs can do, which in turn requires us to remember that not all nukes are the same. The biggest-ever American nuclear test, Castle Bravo, was a thousand times more powerful than Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. To put it in other terms, the ratio between these two is approximately the same as the ratio between Little Boy and MOAB, the most powerful conventional bomb in the American arsenal today. Or between MOAB and an 8" artillery shell. Many of the scarier numbers come from unreasonably large bombs, the vast majority of which have been retired. In practice, most strategic nuclear warheads today are in the 300-500 kT range, with tactical weapons being smaller. If we take the American W88 (455 kT) as representative of this range, if slightly on the larger end, my handy nuclear bomb slide rule2 gives severe damage to typical buildings (5 psi overpressure) out to about 3.3 miles and light damage like broken windows (1 psi) out to about 10 miles. Even 1st-degree burns are unlikely past 8.5 miles or so, and to get slightly sick from radiation would require being within 1.7 miles. For a civilian target, the most important number here is the 5 psi radius, which we can approximate as "destroyed", and all but the smallest cities are more than 7 miles across. If you want to see how this would look in your city (or somewhere you don't like very much), Nukemap is an excellent tool, although it defaults to shooting at the center of cities, which is flashy, but not how targeting actually works (see below).

To put this another way, each bomb can destroy an area of 34.2 square miles, and the maximum total area destroyed by our nuclear apocalypse is about 137,000 square miles, approximately the size of Montana, Bangladesh or Greece.

But of course the bombs won't be spread out evenly in a manner calculated to maximize the total area covered by a 5 psi radius, which brings us to the matter of targeting. Obviously, the actual plans are highly classified, but there's enough in the public domain to let us make some informed guesses. Broadly speaking, we can expect nuclear weapons to be aimed at one of three types of targets: strategic (nuclear) targets, conventional military forces, and industrial/infrastructure targets. Notably absent is a direct interest in killing the opposing population, although people tend to live near infrastructure, so it is going to happen. Obviously, the highest priority is to try to take out the enemy's nuclear weapons and command and control systems, just in case you catch them napping and can avoid getting nuked yourself. But most of these targets are in remote areas, so a lot of warheads are going to fall where there aren't many people. ICBM silos are of particular note here, with the US having 400 and the Russians about 170.3 Each might well get two warheads, given that they're high-priority and well-hardened. That in turn will meant that these are ground bursts, which changes the damage profile (much worse to be right at ground zero, but 5 psi radius falls to 2.1 miles with the W88), but also causes vastly more fallout. But I'm going to be conservative and estimate that a quarter of the global stockpile is going towards such targets.

That leaves 3,000 warheads for the global military-industrial complex, which is a surprisingly small number when you consider the scale of the problem. Possible targets include bases for armies, air forces and navies, factories, oil refineries, ports, railroad marshaling yards, communications hubs, airfields, power plants, and even major bridges. To put this into perspective, there are currently about 1,200 international airports and 732 oil refineries worldwide. Allocating a single warhead to each of these would leave only a thousand or so for every single other target on the planet. Some targets are quite difficult to destroy, which will mean they will need surface bursts, and possibly more than one given the limited radius over which said bursts are effective against hardened targets. Railway marshaling yards are a notorious example of this. Even a major city is unlikely to get more than a handful of warheads, which will be carefully placed to do maximum damage to as many targets as possible, but as these targets don't actually include the local population, the majority will survive. For instance, priority targets in New York City are likely to include Bayonne/Port Elizabeth and Red Hook in Brooklyn instead of Manhattan, as Moscow cares more about New York as a place where armies can sail for Europe than as a place where investment bankers live.

Which brings us to what happens after the war. Even though most of the population, even in quite large urban areas, is still alive, won't they all be killed by fallout and nuclear winter? Fortunately for mankind, this is an area where the public perception bears no resemblance to reality. Fallout is the term for various radioactive particles that return to the surface after a blast, and can be divided into two types. Early fallout comes within 24 hours and is downwind of the blast, while late fallout is worldwide and very dispersed. Airbursts produce only late fallout, and in practical terms, this will have surprisingly little effect. The total yield of our 4,000 weapon war is going to be on the order of 1,800 MT, only 4.25 times the yield of atmospheric nuclear testing worldwide, which even at peak seems to have produced doses of maybe half of natural background radiation. Even if we assume that our war will produce 10 times as much late fallout as the tests (due to shorter timescale and the fact that operational warheads may be dirtier than test ones), the peak exposures are approximately the same as those for aircrew today.

Early fallout is a much bigger concern, particularly if you live downwind from a missile silo. But even here, the risk is often oversold. Calculations here are horrendously complex, but looking through Effects of Nuclear Weapons, it appears that you'd probably be sick but survive 140 miles downrange of our W88 surface burst, provided you took no protective measures at all.4 Even simple protective measures (staying indoors, preferably in a basement or interior room) and evacuation after a few days would be enough to minimize ill effects as little as 70 miles downwind.

Kuwait's oil fields burn

Which brings us to nuclear winter, and in no area is there more disconnect between public perception and reality. The basic idea, that fires resulting from a nuclear war would loft huge amounts of soot into the stratosphere, cooling the planet by 20°C or more and killing crops, came from some extremely simplified models in the 1980s. It was quickly seized by a group of anti-nuclear scientists, most prominently Carl Sagan, who continued to push it even as better models showed that soot production would be lower and the effects of the soot had been overestimated. The real test came in 1991, when Sagan predicted that Saddam setting fire to Kuwait's oil wells could seriously alter global climate, on par with the eruption of Krakatoa. Instead, the soot didn't reach the stratosphere, and was scavenged by rain in a few days. Some have attempted to salvage the theory, but none seem to have really dealt with the problem since. In reality, even a nuclear war 30 years ago would have produced at most a nuclear autumn, and that was with an order of magnitude more weapons than we have today.

The basic conclusion of all of this is simple. Nuclear war is definitely not an existential threat to humanity, much less to all life on the planet. Most people even in major urban areas would survive the initial attack, along with a surprising amount of infrastructure. This isn't to minimize the effects, as it would be a humanitarian catastrophe unprecedented in human history, as the global economy breaks down and regions are pushed back on their own resources. This would likely kill more people than the war itself, particularly in densely-populated areas, but I would expect things to stabilize at a technology level of maybe the late 19th/early 20th century and start back up.

Again, nuclear war is bad, and we should be very careful not to have one, but it is not as bad as it is often made out to be. Some of this is because the threat has routinely been exaggerated by anti-nuclear groups, and some of it is the result of arms control efforts over the past half-century, which have significantly reduced the potential human toll of a nuclear war.5

1 Note that these numbers were as of March 2022. In February 2023, Russia suspended its participation in New START, the current arms-control regime, although it claims that it will continue to abide by the numerical limits of the treaty. China has also commenced a significant buildup, with the DoD estimating they'll have 1,000 by 2030, while FAS estimates 500 in March 2024. ⇑

2 Yes, I have an original version from 1977 which I used for these calculations, so results from other sources may vary slightly. All numbers are for airburst, which is the most effective option if you want to damage a city. ⇑

3 Most Russian ICBMs are road-mobile. ⇑

4 Dose of about 250 rem from 9 hrs to infinity. This is worked out of Chapter 9, mostly using Table 9.93 and Figure 9.20. The unit dose rate of 100 rad/hr is for 1 hr after the explosion, and has decayed significantly in the 9 hours it took to reach the analysis point. ⇑

5 Thanks to John Schilling for his commentary on this post, including several examples. ⇑

Comments

Which suggests maybe they're not as good a target? Why spend relatively precious warheads on a bunch of tracks, rather than bridges or similar? It seems like the same issue with a lot of missions targeting runways rather than hangars or fuel storage - you can fix a runway or a flat yard with a bunch of track relatively quickly (assuming you have earth moving equipment, etc, on hand), but replacing a major bridge is months to years long undertaking.

OTOH, a lot of that stuff has gotten so specialized that you could probably kill the cranes and it wouldn't matter if they could somehow get the rest of it fixed. (Less so for rail intermodal, since you could probably jury rig things with trucks and mobile cranes, but for ship loading it would be a huge constraint).

From the standpoint of prolonged conventional war (i.e. using nukes to support conventional forces in the field by destroying supporting domestic infrastructure) this makes sense, but I wonder to what extent that's actually the best strategy? War is of course the confrontation of forces, but it's also a fundamentally political undertaking, and "we will kill 10M of your people" is perhaps more of a lever to get the other side to sue for peace than "we will nuke Leonardo Pier and parts of Guam". (Or it backfires and makes the opponent more resolved than ever)

I think this is the real risk. The deeply interconnected system of modern supply chains makes them reasonably fragile, and that has knock on effects down the road (i.e. if farmers can't repair their tractors, they can't plant as much, which means less food, etc.), and I suspect but can't prove that there are a lot of "for want of a nail" kinds of dependencies in the economy.

All of this sort of raises the question "What is strategic bombing worth anyway?" Surely, denying the enemy the ability to make war on you from the other side of the world with his home areas perfectly safe is worth something.

I do expect that bridges would be the main target if you're going after railways, and based on Figure 5.140, it looks like big ones would be vulnerable to our W88 out to 10,000' or so.

I'm planning to do a follow-up on strategy and targeting at some point. I do suspect that North Korea at least is basically counting on the "we'll blow up some of your cities" effect, because they don't have the weapons to seriously attack the US economy.

From a deterrence perspective, the other side needn't know whether you've gone for counterforce targeting or countervalue.

Something I've been meaning to ask of you guys: what's the deal with the reduced yield W76-2? Is it a strategic decision, or are they simply not able to keep them working as designed?

Does the US just not have enough tritium to fuel even just their deployed warheads?

If that's the case it seems like the stockpile weapons can be disregarded entirely.

@Lambert

Assuming you have a sufficient quantity of credible weapons in terms of accuracy and so on, I agree there isn't any trade-off between the two. Indeed, you can switch between the two as fast as you can reprogram the guidance. For deterrence that seems sufficient.

But if that deterrence fails, at some point you have to choose what you launch at, particularly if the exchange is protracted rather than launching everything immediately. I suspect that the high value counterforce targets get first priority (silos plus SSBN bases), but after that do you pursue straight counterforce, countervalue, or some mix of the two? Does that change if they start with a tactical nuke?

(Or for that matter how do you game out first use?)

@redRover

I know that if I was planning a retaliatory strike, I wouldn't be aiming for SSBN bases, nuclear C&C or silos - because those have already launched their shot, and hitting them won't reduce the number of warheads incoming.

But then, I'm also the sort of person that thinks the game-theoretic optimal response to seeing Russia launch everything might just be to hit the population centers of not just Russia, and not just Russia+China, but both of those plus every single other major or hostile nation. Including "allies" like Saudi Arabia, and perhaps even the UK and France.

The idea would just be to make sure no one gets creative with false flag attacks. Getting Enemy A to nuke Enemy B and B to retaliate against A is probably the wet dream of a few people in C, D, E and F after all - and knowing that the retaliation will be indiscriminate might discourage such things.

bean:

Even then temporary bridges exist and can be deployed pretty quickly.

To really knock out a railway you'd have to collapse tunnels, or just go after the oil refineries so they won't have the diesel to fuel the locomotives, power plants so they won't have electricity in their wires and industry so they won't have anything to put on their trains even if they can somehow power their locomotives.

DuskStar:

No one has enough nukes for every enemy target they'd like to destroy and I doubt they did even at the height of the cold war.

If the dispute has an ideological component you probably want other countries with similar ideology to survive, even if your country is destroyed so have a really strong incentive not to target your allies (unless you think they'll switch sides without you to coerce them).

@Echo

The Trump years saw some weird stuff going on with the nuclear arsenal, with a lot of discussion of low-yield nuclear warheads. I think the theory was that it would give us a small nuclear option if we needed one for some reason. The problem, of course, was that it was a stupid plan. If we need to just nuke one thing, use a bomber. Ballistic missiles tend to make people a bit nervous.

@redRover

The problem with ICBMs is that they pretty much have to launch immediately, because otherwise the risk of being destroyed in their silos is too great. You might have some option to wait with SLBMs and bombers, but even then, those are wasting assets and you'll want to launch pretty quickly.

@DuskStar

Don't aim nuclear weapons at your allies. It's a bad look, particularly if the plan gets out. I'm sure that the Soviets had a plan to take out most of the Warsaw Pact if NATO didn't, but that's because they were only allies thanks to the Red Army, and I'm sure the Poles would be delighted by a chance to oppress Russia in the aftermath of a nuclear war.

@anon

For road vehicles or short rail bridges, sure, temporary bridges can work. But I think that's less feasible for things like crossing the Mississippi or other major rivers, where you not only have the river itself to bridge, but also a significant elevation delta to overcome between the built up approaches and a water level temporary bridge.

Also, I wonder how much emergency bridging material is actually on hand or reasonably available. As we've seen with Ukraine, Libya, and other operations, there often isn't that much in the warehouse.

@bean

Yeah, one single strike seems like the best way to avoid losing capacity to counterstrike. But if the exchange starts out with a single tactical nuke I'm not sure if they would go immediately to full "launch everything" in retaliation.

Tangentially, this is also why "Duck and Cover" doesn't really deserve the mockery it gets. Sure, if you're just a few blocks away from ground zero, there's not much you can do but put your head between your legs and kiss your ass goodbye. But as you point out, lots of people live and work in areas that are near primary targets but not so near as to be doomed no matter what.

If you're 1-3 miles away from ground zero, the main immediate dangers are going to be burns from the thermal flash and getting crushed by falling debris. Huddling underneath a sturdy piece of furniture and shielding your head with your arms helps quite a bit on both fronts: you break line of sight for the thermal flash, the desk or whatever will give you some protection against debris, and if that's insufficient then better your arms get hit than your head.

Admittedly the case against civil defense was somewhat stronger at the height of the Cold War, when the deployed nuclear arsenals we're considerably larger, strategic warheads were substantially bigger (to compensate for shortcomings of missile guidance at the time), missile defense was much more primitive as well as being sharply limited in deployment by treaty, and living patterns were more urbanized so more people lived or worked in close proximity to industrial and infrastructure targets. Even then, though, good civil defense probably had the potential to save millions of lives in the event of an all-out nuclear war.

@Echo:

It's a strategic decision. The (highly controversial) rationale is that the US needs low-yield nukes in order to respond in a proportionate manner if Russia uses their low-yield nukes. Even if you accept this argument, it's unclear why the B61 mod 12 with adjustable yield from 0.3 to 50 kt wouldn't be sufficient.

FAS had a nice explanation of the W76-2 program: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2020/01/w76-2deployed/

@Eric

I've always detested the smug belittling of "Duck and Cover" for exactly the reasons you lay out. I'd add that in the post-attack environment "minor" injuries are anything but, and surviving medical resources would be stretched far beyond their breaking point.

@Anonymous

While you might not have enough nukes for every enemy target, you also don't have to prioritize enemy military assets to nearly the same extent as you would in the situation where you are the attacker. You're not trying to hit all of their nukes to prevent retaliation, you're trying to inflict maximum damage to their civilian populations, governmental bodies and religious institutions to discourage being struck in the first place, which should be a rather different target list.

10 warheads per city is still 150 cities.

If you can count on your allies to actually follow the same ideology after the fact, maybe. Can you say that for the Saudis?

What's the chance of some Islamic terrorist pulling the plot from The Sum of All Fears (where a homemade nuke is detonated at the super bowl, killing the president, at the same time as false flag attacks are launched against the US, with the intent of sparking a nuclear exchange between the US and USSR) instead of the ending of Debt of Honor (747 suicide into the US capitol)? Does that chance go down if it is known that pulling it off means Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem are on the canned sunshine delivery list?

And if there's nukes flying at you, but none at the French, perhaps someone cut a deal - or forced a confrontation that would bump them from 5th place to 1st.

@Bean

Agreed that it's a rather remarkably terrible look. But so's eating your babies in times of hunger, and plenty of species do that.

The optimal decision tree might not be anywhere close to morally acceptable, but when playing the game of megadeaths some people will throw those considerations out the window.

DuskStar:

No, but you've still got all their industry to destroy.

DuskStar:

DuskStar:

You'd need more than 10 warheads for a large city (such as say, Moscow) and with some cities having ABM defenses and the fact that some of the warheads will be duds and some of the missiles will just blow up on the way (from what I've heard a ~50% failure rate without enemy intervention was expected).

Also not everything that needs nuking is even near a city, even if you restrict yourself to civilian targets.

DuskStar:

Not for the Saudis, but without anyone buying oil from them they're basically irrelevant.

NATO and many notable non-NATO allies of the US could be counted on to continue democratic capitalism and assuming the US doesn't nuke them can be counted on to help out whatever is left of the US.

Kind of amusing that Posadists thought a nuke fight would be a good thing because it would cause the whole world to become communist.

DuskStar:

But in this case it turns out that the immoral act you propose would actually be terrible strategy, at least for the US and any country like it.

“from what I’ve heard a ~50% failure rate without enemy intervention was expected”

I’ve seen that number at, for example, the Titan Missile Museum. It probably made sense for planning purposes with early generation liquid ICBMs like Titan, and when you had an order of magnitude more nukes you could afford to be conservative in your reliability estimate.

But I suspect modernized Minuteman/Trident to have a much higher success rate. Well tested all-solid rockets with solid state electronics stored in air conditioned silos are very likely to work. No idea about the actual nuclear detonation reliability, but the delivery system reliability is probably closer to 90% or more?

I've seen reference to 90% assumed reliability for ours and 70% for Soviet missiles in some declassified analyses.

That was for late-generation silo-based ICBMs, I should add.59

I recall during a few exercises I participated in at one of the War Colleges there were two retired O-6s (one Army and one Navy) who were always talking about EMP and the outside effect it would on our population centers... well actually anywhere for that matter.

I was too busy to sit and chat with them, but they were apparently quite loquacious in describing apocalyptic scenes should such a weapon detonate in the mid altitudes.

I recall some time later trying to Google what they were talking about but I never came across what appeared to be a rational discussion.

Any merit to their fears that this would be measurably worse than any other type of high yield weapon directed at the targets you all describe above?

@Neal

My understanding (John has looked into this more than I have) is that EMP is rather overrated as a threat. Yes, it can destroy stuff hundreds or thousands of miles away from the blast, but it usually doesn't. The vast majority of stuff, and basically all military stuff, will still work. Starfish Prime (IIRC) did knock out electricity to a street or two in Hawaii, but there are lots of streets in Hawaii.

Gbdub:

Directrix Gazer:

But none of the currently used systems ever had an all-up test.

bean:

Also more than a thousand kilometers away and it affected equipment inherently less susceptible to EMP than modern unhardened stuff.

There are branches of engineering that are set up to deal with problems like this. Is there some remaining uncertainty? Yes. But it's not enough to imperil the whole deterrent. I would be in favor of resuming underground nuclear tests, at least on a small scale, but the 70-90% range seems entirely reasonable.

Not exactly. EMP is really complicated, but the basic issue is that even kilotons worth of energy just isn't that much when you spread it out over the entire United States. So it's only likely to affect large objects, because small ones won't pick up enough to matter. The stuff about microchips being more susceptible is true, but I think matters only for the close-in EMP. Which I didn't discuss here because it's going to be fairly far down your list of concerns if a nuke drops close by. EONW Chapter 11 has as much detail as is publicly known on this.

Also on the effects of Starfish Prime, the only damage to civilian electronics was blown fuzes and popped breakers. Neither the burglar alarms nor the streetlamps were actually damaged. The most likely damage for a high-altitude EMP is knocking out systems briefly and forcing reboots, not killing all electronics over the US.

IMO the real question is "how correlated are the failures". Say, in 95% of possible universes matching our observations 95% of warheads launched detonate in the expected area, and in 5% every single one fails due to some unforeseen design issue during reentry.

DuskStar:

As much as you can determine individual component reliability without an all-up test you can't truly rule out the possibility of an interaction between components.

The best way to deal with it if all-up tests are illegal is to have many different designs, that way if one has an issue that causes all of them (or even just a significant percentage) to be duds the others should at least work.

Agreed..

Speaking as someone who has spent a fair amount of time around climate models/science, the Nuclear Winter scenario does not feel right - by a simple comparison, the Krakatoa eruption was of a similar magnitude to a full nuclear exchange, but probably putting more particulates into the stratosphere because it was all in one place, and that did not cause such a winter. Effects for a few years, yes, but not a global apocalypse.

I also can't see why, for example, China would join in to a NATO-Russia nuclear war. Presumably the US would keep a couple of SLBM submarines available to hit China 'just in case', but China gains nothing from joining in and benefits hugely from getting through unscathed. Likewise India, and I doubt that South America or Africa would be on anyone's target list.

The biggest killer would almost certainly be the collapse of agricultural supply chains. Ironically, this is where you want to keep your enemy population alive - suddenly, feeding them becomes a huge burden.

(Of course, I live in the UK, which is small in area, has a high density of targets and is dependent on food imports. Plus I need some fairly hi-tech medication to stay alive. Don't think I'd be on the survivor list..)

Andrew Dodds:

China may be the one neutral country that it would be worth nuking in a real life game of global thermonuclear war even if they didn't start it for exactly that reason.

@Andrew Dodds: "I also can’t see why, for example, China would join in to a NATO-Russia nuclear war."

First, because they couldn't be certain that no warheads would be headed for them. The flight paths, and thus targets, of ballistic missiles are easy enough to predict once you detect them, but bombers are another matter. And their proximity to Russia means the Chinese leadership would have to make their decision to launch or not very, very quickly.

Second, and closely related, because AIUI the Soviet plan was to not let the PRC (or India, or some of the larger/more prosperous places in Africa and South America) sit out of a nuclear war. And if the current regime in Moscow has moved on significantly from the old Soviet playbook that's not at all clear to me.

It's not really up to China whether to join or not. From Russia's perspective, the choice is between getting hit by the US arsenal + 10-15%, with most of those extra warheads bouncing rubble created by the Americans, or getting hit by just the US warheads, plus the Chinese Army invading soon. And I suspect they're paranoid enough to fling a couple warheads at lots of other people, just to slow down their recovery and keep their armies at bay long-term.

Every warhead sent to China or someone else is a warhead that isn't going to the US/Russia and as I said before, there are more targets than warheads.

bean:

More a short-term thing, long-term it'll just piss people off and you'll have spread your nukes too thin to prevent recovery.

I can't see it making any sense for anyone not on your border or for a neutral but probably hostile country that could end up hegemon.

The more interesting question is whether a US-China nuclear war will involve Russia. Both sides have a fairly large incentive not to poke the half-Gigaton bear, and Russia has an incentive not to do anything that will attract too much of a second strike.

I'm not sure China's incentive is actually to keep Russia out. It's extremely cold-blooded, but there's going to be a lot of overlap between the Russian and American targeting plans, and there's also the risk of the Russian army showing up a few years after the war. Also, if they can trigger a Russian-American nuclear war, that's going to do a lot more damage to America (and Russia) than they can on their own.

Also, isn't China still on the budget MCD doctrine?

Pretty much. They have enough to make it painful, but not enough for "assured destruction".

I just realized that there was a major mistake in this, and nobody caught it. I got the number of Minutemen in a Wing (150) confused with total Minuteman inventory (450) when talking about land-based ICBMs. Or, more accurately, I thought we were down to a single Minuteman base for some reason. Can't think why, and in practice that should soak up a lot more of Russia's warheads. But I'm going to change as little as possible in fixing it.

This clinical assessment is disturbing to say the least. The extent of the horror, suffering, and human debasement of nuclear war is beyond description even if as the author notes, it won’t bring an end to humankind. I fear this kind of assessment makes nuclear war more likely.

Exaggeration of the danger also poses serious danger itself.

Many of our preconceptions of nuclear war come from the 1960s where a combination of Neville Shute's On The Beach and Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove gave us the idea of the massive radiation cloud that encloses the planet and kills every living thing.

In both of these scenarios the nuclear weapons were "seeded" with cobalt, which theoretically would induce toxic radiation with a hundred-year half-life.

This idea came from none other than Douglas MacArthur, who wanted Curtis LeMay to bomb the length of the Yalu with just this type of nuclear ordnance in order to create a "corridor of death" that would prevent the Chinese from swarming down into North Korea (which they were currently doing).

Dugout Doug came within a few days of doing this before Truman relieved him for insubordination, and LeMay had to content himself by using the conventional method perfected over Japan: B-29s flying at low altitude dropping M-69 napalm bombs.

Over the next three years he did just that, destroying almost every single structure in the entire country of North Korea before turning his attention to bombing their hydroelectric dams.

Did this weaken the resolve of the population to fight the Americans? Not in the least, any more than it did in Japan (counter to what you read in history, the firebombing and atomic attacks did nothing to weaken the Yamata Dashii of the Japanese people; instead it was the threat of the Red Army invading Hokkaido and sweeping across the island while the Americans pushed north from Honshu).

The only result of killing civilians is long-term hatred, especially evident in NK.

I am glad people are terrified of nuclear war in the way they are because the moment they learn differently we're back to the horror of it. It's like regular war, but people die way faster.

@Anonymous

The same is true of regular war.

J Hardy Carroll:

It was Leó Szilárd who came up with the idea of the Cobalt bomb.

Also fighting in the Korean war paused mid 1953 while the first practical thermonuclear bomb the US tested was exploded in 1954 so the US did not actually have the technology to make salted bombs while the Korean war was being fought.

J Henry Carroll:

⁶⁰Co has a 5.27 year half life.

J Hardy Carroll:

You do realize that nuclear weapons use in the US requires Presidential approval?

Meaning that a general can not order the use on his own initiative, merely argue that they should be used.

J Hardy Carroll:

The Japanese population was never given a say in the matter.

J Hardy Carroll:

Japanese leadership was willing to suffer millions of deaths in that process so it is most likely that had the US not nuked them that the war would have ended by invasion (and I suppose you're also going to say that both the US and Japan were wrong about how many would die).

J Hardy Carroll:

An oppressive dictatorship where the population is indoctrinated to hate the US.

Did you ever consider that maybe it might be the indoctrination that causes the hate? Or even just fear that anyone not publicly hating the US would be sent to a death camp (which North Korea totally has)?

J Hardy Carroll:

There are things even worse than nuclear war.

Besides, had you actually read the OP you would know that nuclear war is still going to be a bad thing, just not as bad as you imagine it to be.

Anonymous:

I could ask you the same question.

Anonymous:

Some of us are pretty far away from targets so would be likely to survive.

I should probably state the obvious here. Saying this stuff did not make nuclear war more likely. Everything here came from sources freely available to anyone with an internet connection. And it's generally safe to assume that anything I can figure out can also be figured out by the advisors of the people who actually control nuclear weapons. They're going to know better than I do what the actual consequences would be. You could argue it would be better if those people were deluded, but if they're deluded about this, they're probably deluded about other things, and that seems likely to be much worse on net.

Also, drive-by Anon calling me stupid? You forget that I have a ban button, and will not hesitate to use it if I get annoyed. I'm kind of annoyed over this. That said, if this continues, I may lock down comments on this.

@J Hardy Carroll

I think you overestimate both MacArthrur's ability to execute a nuclear attack on his own right, and the effectiveness of the bombing campaign against North Korea. They got really good at repairing their infrastructure.

More accurately, only evident in North Korea. 8 years separates us stopping bombing Japan and stopping bombing North Korea. Heck, we bombed Vietnam 20 years more recently. And yet we're more popular in Vietnam than in North Korea (and yes, I'm aware the campaigns were different) and we were way more popular in Japan 8 years ago (or 40 years ago) than we are in North Korea today.

Also, any comments accusing me of being part of a death cult or the like will be summarily deleted. If you think I'm wrong on the object, feel free to challenge me, but I don't see any reason I (or anyone else) should have to put up with abuse.

Here's Luisa Rodriguez's very detailed analysis of how bad a nuclear winter would be. She was paid by one of the Effective Altruism orgs (I think Rethink Priorities) to study this: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/pMsnCieusmYqGW26W/how-bad-would-nuclear-winter-caused-by-a-us-russia-nuclear

I don't follow how the reasoning whereby everybody dies in a famine after a few degrees of cooling works. You could cool the Congo down by 10°C and it'd still never go below freezing. For the tropics (home to several billion people), I'd expect a fall in the carrying capacity of the land rather than farming becoming altogether impossible. And even a 99% drop in the tropical population leaves a world with a lot more people than just a few million Kiwis and Aussies.

@bean:

A really uncomfortable would also discuss "racism" as why the Norks don't like Americans (or anyone else!). Can recommend The Cleanest Race by B. R. Myers for further about this if anyone is interested (sneak peek of some of the book here).

There are some additional points to consider. While there may be only poor models available to predict the affects of a nuclear winter, the affects of radiation are quite good and have been qualified for quite some time.... The fact that the discussion addresses ground burst events with only a minimized and passing reference to fallout from a ground burst is ... unfortunate. The maximum dosage of radiation is specified as 5 rem per year...... A ground burst of a W80 (I juiced up the yield a little) yields a 1 rem per hour radio active area of nearly 14000 square km (can be logically extrapolated into a much larger area). A mere 100 warhead of this size (Trident delivered) would render nearly 20% of the lower 48 states in the US (1400000 square km of a estimated ) an immediate dead zone (Wellerstein). This alone undercuts the argument associated with the topic at hand.

I think the point was that (most) humans can take shelter for a few days and effectively dodge fallout, which doesn't persist in time, if I understand the concept correctly. Unless your source refers to actual, significant, sterilization - which sounds unlikely.

Typo?

5 rad/year is the result of some very cautious analysis. In reality, you can survive a lot more than that with an elevated risk of cancer.

The fallout analysis is the area I'm least confident on my math, but I don't think I'm wrong. Maximum fallout intensity decays fairly rapidly due to the fact that it's mostly from short half-life stuff. My "probably be sick but survive" is within the area he gives as having 1 rad/hr, and by 3 days post-attack, the radiation in that area should be down to only .1 rad/hr. More than that, someone who stayed in the area and didn't take shelter would have gotten about 40% of the radiation they'd get if they stayed in the area forever. I'm not going to do detailed math because it's a pain to do by hand, but the vast majority of that area is going to be in the "increased cancer risk in a decade+" rather than "prompt fatality" category within a few years.

LOL, well if you don't think that consuming 5 times the yearly rate of radiation in one day isn't much of a problem, then there is a large gulf in what we believe is problematic. Also remember that this is at the "periphery of the fallout area. The fallout becomes much more intense closer to the ground burst. Additionlly, The fallout area of one explosion is large enough that it would be problematic to evacuate without exposing a large numbers. t

I am less sure of this. If you're within maybe 50 miles downwind, there might not be time to evacuate and sheltering in place may not be practical for the time needed. Beyond that, you could probably get out, and even if you can't, you should be able to shelter for a few days until it gets low enough to safely evacuate.

Sigh. It's a problem. A general nuclear war would be, by a substantial margin, the worst thing that ever happened in human history. If it occurs within the next twenty years, so it's within about 100 years of WWII, I'd posit there's a good chance popular history books 300 years from now will have that conflict as a footnote to the far more horrific destruction that occurred during this hypothetical nuclear exchange, as things get compressed in pop history retellings.

But the point is: there's going to be a popular history written, because while it's a problem, it's not an "EVERYBODY ON EARTH IS GOING TO DIE!!1!" problem.

This distinction matters. Because right now, many people seem to think that nuclear weapons are magical. If they're in an area where the bomb will affect them, they're just going to die instantly as they get vaporized or every single building gets blown flat. That is very much not true: most people outside of a small zone around the bomb will survive, but not if they do stupid things. But the hell of it is, if they do stupid things that get them killed, it's likely it won't get them killed instantly. It'll get them killed in horrific ways where it takes them hours or days to die, and it will hurt for the entire time.

Your sneering about a 5x of the standard yearly limit dose is an example. It is very much true that this represents an increased cancer risk and not immediate death, and it's deeply weird that you feel threatened when this is pointed out. Because if you get people who cling to the false belief that this is worse than it is, they're likely to not bother to take any sorts of precautions in the aftermath of a nuclear detonation because "it's not like it matters." So instead of maybe dying from cancer in 10 or 20 years, they wander around outside in the immediate aftermath of the blast and get a lethal dose from fallout and die of acute radiation sickness. Which is absolutely horrific itself, probably giving cancer a run for its money.

Even assuming that ARS is less painful than cancer, this still isn't better: I'm willing to bet that if you were told 100% that you're going to get cancer and die from it in 10 years, your first reaction will not be to walk out of the doctor's office and jump off the roof. Because an extra decade is a fair bit of extra life and you're probably going to take advantage of it!

Feeding people doomy crap that basically makes them commit suicide in the aftermath of a nuclear attack--whether through neglecting to be careful or just making them think that actually committing suicide if they happen to survive is a reasonable course of action--is not doing them a kindness. If you're unfortunate enough for this to happen to you, work to survive, and take basic precautions to avoid things that might kill you. You always have the option to kill yourself later if you do decide life isn't worth living--and probably in a way that's going to be less painful than the prompt effects of a weapon--so don't forgo that option out of ignorance, nor take it away from others with lies.

where did you get the information that the average nuke yield is between 300 to 500 KT?

Anywhere that has a list of nuclear weapons. For instance, those for Russia and the US. I used the W88 as a plausible high end, and the actual average is probably lower, brought down by the lots of 100 kT warheads on Russian missiles.

thanks, do you perhaps have a list for china's arsenal

Estimates from the same source are here.

I came to this blog for the battleships, but here I am reading about nuclear war. I didn't expect to have my thoughts provoked. Fascinating conversation, and I'm writing the 57th comment? Impressive.

I agree with J. Hardy Carroll that our opinions about nuclear war have been formed largely by movies and literature. Carroll cites two examples, but everyone reading this blog could come up with many more. The 1983 TV film The Day After did a lot to foster the idea of such a war as a world-ending disaster; it has its own Wiki page. It's worth reading.

Joanna Russ once remarked that what's missing from after-the-bomb stories is the preexisting condition. If the day before they drop the bomb, you need dialysis, insulin, blood pressure or anti-depressant meds, or even glasses, then the day after they drop the bomb you will be in big trouble. But that would get in the way of the story. The only such instance I can think of is the Twilight Zone episode where the myopic Burgess Meredith survives a nuclear blast only to lose his glasses.

eading this post and the R56 preceding comments made me want to revisit John Hersey's Hiroshima and Robert Trumbull's Nine Who Survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hersey and Trumbull don't try to hide the horror. But in both books, there is reason to hope. Humans try to survive and do better in the future.

Much enjoyed the discussion, except when things got heated. Come on, boys, I liked you better when you were arguing whether Guam and Alaska were or were not battlecruisers. (Of course they were.) (I wrote that to piss off half of you. Just kidding.) (Or am I?)

Mini rant below

Note: I'm assuming many of your readers will be familiar with part or all of the facts below, but I'm dropping this here for less-informed visitors following a web search or algorithmic link.

My personal opinion is that the uncontrolled journey of a nuclear war escalation ladder/vortex/escalator likely would end with counter-value attacks on the populations of all combatants. A buffet meal of canned instant sunshine makes for a very bad day.

The author of the OPEN-RISOP project ( https://github.com/davidteter/OPEN-RISOP ) worked as an US DOD war planner - an engineer for planning the destruction of the Russian infrastructure and population - and he has ZERO optimism about surviving a nuclear conflict.

OPEN-RISOP project README file:

A part of his background:

An example of his dismissal of optimistic survivalist "prepping" for nuclear warfare: ( https://old.reddit.com/r/war/comments/trkfe7/threehypotheticalscenariosfora_russian/i2n638h/ )

Given that he is a professional expert on selecting the types of targets, and on the predictable effects of hitting those targets, it seems foolish to assume most of us would still be around for long after a "general war" counter-value nuclear exchange.

In addition to buried bunkers and missile silos, some reinforced concrete structures (e.g. dams) and some steel transportation structures (e.g. railyards) would have been targeted with ground bursts to ensure that the space formerly occupied by that structure would be replaced by a crater and the vaporized remnants of the target.

The people killed by downwind radiation fallout was a collateral damage "bonus" in counterforce attacks (destroy weapons and infrastructure), and part of the intent in countervalue attacks (kill the population).

Note: many more warheads are needed for counterforce then for countervalue.

The majority of people in urbanized environments will need something that will no longer be available - or will be caught in the effects

Most people rely upon the functioning and existence of the products of global supply chains, and will die from starvation, disease, or lack of medical facilities after a nuclear exchange has smashed crucial parts of those supply chain inter-dependencies into bouncing piles of flaming debris.

And those effects are The Point of Assured Destruction

https://archive.org/stream/DTICAD0750721/DTICAD0750721_djvu.txt

It's a pretty grim scenario, and I don't really like thinking about how bad this would become, but I also don't want denial / false hopes to get in the way of understanding the realistic effects of a nuclear conflict.

Note: a friend served on a USN submarine as noted that if he was at sea when orders arrived to launch their second strike weapons -- his family, friends, and the alternate crew probably were already dead, or very soon would be dead.

I had run across OPEN-RISOP a few years ago, and remember being pretty unimpressed, although I can't recall the exact details of my disagreements. Based on what you posted, I would lean towards "no, you're still catastrophizing".

I don't think that's a good assumption. Reading between the lines on the posted bio, he wasn't actually doing nuclear targeting. The one claimed accomplishment was in helping plan B-2 missions, which is a thing you do after you've selected targets, and the weapons involved aren't always nuclear, as we have just seen.

That's not what countervalue is. Countervalue is going against infrastructure. I've never seen a serious plan by a major power where "kill as many people as possible" is the objective. (This is sort of how North Korea is doing things, but they have a lot fewer bombs to play with.) You don't need it. Anything that can be accomplished by killing a lot of people can be accomplished if you shoot them at industrial targets.

And yes, that would be very, extremely bad. I can absolutely buy above 50% dead within a year, and 75% isn't outside the realm of possibility. But we are in a world with relatively small arsenals, so the actual damage from the strike is smaller than you'd think. There would still be intact hospitals. Not saying they'd be well-supplied, but it's not like all medical care would go away instantly. There would still be a lot of ag infrastructure, and while diets would be bad and monotonous, not everyone would starve.

Also, quoting Robert McNamara is not a particularly good way to convince me of anything, given that I view his strategic theories as one of the worst things to happen to the US government in the 20th century.

First, thanks for your blog posts, I've found them informative and entertaining.

Well, I did start by labeling my comment a rant ;)

Having never been cleared to see any war plans, I'm limited to commenting based on reported of public statements and other open source information.

Such as these brutal gems related to France's deterrent: from the wikipedia article on the French nuclear deterrent

As to David Teter, his bio lists the 2000s SIOP replacement projects "OPLAN 8044 and OPLAN 8010 are both successor plans to the Single Integrated Operational Plan, the general plan for nuclear war from 1961 to 2003"

I am curious what issues you found in his OPEN-RISOP project.

Despite whatever issues one might have with McNamara, he was the Secretary of Defense when stating that Assured Destruction goal -- which was a reduction in the "bouncing the rubble" overkill carnage from the plan he inherited.

A nuclear war would be catastrophic for those in targeted areas, and for those downstream dependents of the vital services and supply chain outputs that were converted to debris.

Focusing solely on infrastructure destruction as the goal of countervalue seems like a comforting euphemism, used where a clear and blunt description of the predictable effects on the population could be more informative.

People tend to cluster inconveniently close to infrastructure. So destroying the Infrastructure targeted in a countervalue plan implicitly will kill both those who were too close to the targets, along with those whose survival depended upon those infrastructure systems.

If someone survived the blast / heat / radiation effects -- but succumbs days (or weeks) later to hunger, thirst, disease, or lack of treatment from dead/overloaded paramedics and hospitals -- they're still just as dead.

National populations also tend to cluster more closely than expected. See image web search results to query string "3D population density maps visualizations" for examples of the relatively small portions of a given region containing large percentages of the residents.

Note: when I lived and worked a couple miles from the "Blue Cube" in Sunnyvale, it was oddly comforting to know that if the Cold War had turned hot in the 80s, the warheads dropped on that NORAD facility probably would have ended the conflict very quickly for me.

Thankfully, the peak stockpiles of 20,000+ warheads each for USSR and NATO were trimmed down.

These recent comments are playing fast and loose with the date.

I have no trouble believing the 1984 Soviet arsenal would be apocalyptic. But the 2025 Russian arsenal? Around 1600 strategic warheads with delivery vehicles capable of reaching the U.S.? Even assuming there is zero interdiction and the Russians move first, you have to figure half of them will fail in operation. That gets us down under a thousand warheads, and that’s just not enough to go around. That’s barely enough to address the Minuteman system.

Don’t get me wrong, it would really suck to have to ride that out, but most of the country would live and most cities would see exactly zero weapons impact nearby.

I'd hesitate to assume Russian nuclear forces are as incompetent as the rest of their military.

Similarly to how their submarine force is leagues better than their surface navy, the Russians are able to maintain first-rate capabilities in their most important units.

To the contrary, I assume the Russian nuclear forces are competent but poor. The American stockpile stewardship program is expansive and expensive. Can the Russians afford something similar? For that to be true, you have to assume that they are unusually well funded, when, by all appearances, everything strategic in Russia has fallen by the wayside in pursuit of more tanks for Ukraine. Even the submarine forces, which are well regarded for quality, exist in much smaller quantity than they once did. How many boomers do they have at sea?

I make the point of unreliability because (1) it's likely correct, (2) the Russians need to worry that it's correct and plan targets accordingly, and (3) it makes it obvious the numbers are too small for the job. But even 1600 warheads assuming no interdiction (Really, no interdiction? Is that at all plausible?), and assuming they all work, is still a small number if you plan to attack military targets.

And this is where competence comes in. There's no way the Russians are targeting Manchester, NH and Clarksville, TN ahead of the Minuteman silos and Kings Bays, Georgia and Washington, DC and Whiteman AFB, and other military targets that are going to eat up a lot of warheads. In grad school I had an assignment planning a strike targeting the greater Boston area. If I remember correctly we used around 15 warheads. Hanscom AFB got four just to crater the runways. Today, I'd be surprised if Boston rates one warhead in the primary Russian strategic plan. Probably it gets one in some "we've already lost" revenge-oriented backup plan. If you can spend 15 warheads on Boston, you may very well get pessimistic's outcome.

Don't get me wrong, I'm not trying to say this would be fine in any respect. What I'm trying to say is that there are degrees of bad, and this is not nearly as bad as things were in living memory. We're at the brink of a major disaster, but we're not at the brink of a civilization-ending calamity. The bad guys just don't have that capability anymore. It's important to think clearly about this because we should value the difference between 2025 and 1984 and do whatever we can to prevent the 1984 situation from arising again.

pessimistic:

Yes, but even at the peak there would still be survivors and plenty of places that weren't glassed that could help out what was left of the US be rebuilt (while preventing the Duchy of Moskva from being a threat ever again).

Coffeebean2017:

True, but the rest of their military sets a pretty low standard.

@pessimistic

You are quite welcome.

Yes, I know. That doesn't mean he picked targets or even saw the target list. His specifics list work on B-2 routing software, which is absolutely the sort of thing that feeds into SIOP, but can be developed on fake target data.

Unfortunately, I don't recall, because this was several years ago, and one of the downsides of blogging about a lot of stuff is that I often remember little more than what ends up in the finished product.

That's a complicated issue, and I've seen an argument that a lot of the rubble-bouncing was really an attempt by SAC to build in safety margin in case things went wrong.

I am very well aware of this. But it's not so tightly that "limited blast radius" doesn't also apply. I did a serious attempt at a targeting workup on St. Louis once, and I think I ended up with 10% dead and 30% injured with 6 warheads.

@anon

Pretty sure it rates more than one. Hanscom is still a major hub for Air Force logistical stuff, and Raytheon has a couple facilities that you'd want to get rid of, if nothing else. Also not sure why you'd need four to crater runways at Hanscom. A single crater plus fallout seems like enough to me.

Disagree on this point. If the Russians don't have enough warheads to plausibly neutralize the Minuteman threat, and aren't stupid, then they aren't going to waste any of their warheads on Minuteman silos. Destroying only half the Minuteman silos doesn't save Russia from annihilation. Convincing the United States that war with Russia means that all of America's cities will burn, might. And if it doesn't, it's going to feel a whole lot better than making craters in Montana.

You might as well argue that the United States has little to fear from North Korea's nuclear arsenal, because they'd just use it to blow up King's Bay, Whiteman, and four Minuteman silos.

High-leverage military targets like King's Bay and Whiteman are probably on Russia's list. But by the time they get to a hundred aimpoints, it's almost certainly going to be dominated by "how can we make the Americans suffer most with the next warhead?". And that doesn't mean Minuteman silos, or a fourth crater at Hanscom.

If you look at a map of Hanscom, you'll see why. The idea was to break each runway into segments short enough that they couldn't be used by heavy aircraft. The longer runway at Hanscom is quite long.

We also wouldn't rely on fallout to keep it from being used as a bomber divert base in a protracted conflict. Imagine a nuclear exchange playing out over a month or two. One bad hour was not the only thing looked at.

This depends entirely on what kind of attack you're looking at. If it's a second strike targeting cities, it almost certainly will consist of a lot less than the original 1600 warheads. If it's a first strike with the full set, it's likely to be almost entirely allocated to counterforce (with the proviso that some cities, like DC, are going to be swept up in a counterforce attack).

This also depends on a degree of guesswork as to what someone else's priorities are.

It's only 7000', which is pretty short by the standards of bombers. A single groundburst near the middle of the X is going to leave you with the longest runway being 4000', minus the crater itself, which should have a radius of at least 750'. You can fly some planes from a 3000' runway, but nothing very big, and there are enough 3000' runways in the country that if you start chasing every one with nukes, you're going to run out really quickly.

Fair enough. We had rules we had to apply, a budget of the kind of warheads we could allocate, and an attack context. But the presumption was that large airfields were going to get systematically attacked like that. Logan got a similar treatment. Heck, if I recall correctly, the Kennedy School got a warhead, although that may have been because it was roughly in the middle of a bunch of soft targets rather than it being a high priority target per se.

A 750 foot crater requires a fairly large warhead, maybe not the kind that would get allocated to Hanscom. It's been a while, but the constraint may have included that we were getting an allocation from one or two SLBMs. We had effects calculations to make as part of the process, IIRC.

750' was what the slide rule gave me for 300 kT. Maybe it's a bit big, but I'd have a hard time buying it taking more than one for any effects you'd want on Hanscom's runways with any warhead you might describe as "strategic".

What is it that you imagine Russia would be imagining it could accomplish with a first strike of ~1600 dubiously-reliable warheads?

This seems off to me. Sure, if you're trying to win the war and come out as a functional society that can pick up the pieces, you destroy the enemy's military capability. But if you know you're going to lose, wouldn't you go for the population centers and industrial capacity, and make sure the enemy knows it, for deterrence? There's no point in destroying one-third of the enemy's military if the remaining two-thirds can glass you twice over; it seems useless to start counterforce targeting until the marginal missile destroyed actually saves you something in the aftermath.