Naval strategists on both sides of the Iron Curtain quickly saw the potential of the submarine as a platform for delivery of nuclear weapons. Unlike any other means of delivery, it offered the opportunity to get in close to the enemy's coast, even in the face of enemy forces, and emerging cruise missiles gave it a weapon capable of striking targets far inland.

A Shaddock missile

The Americans were the first to get a system to sea with Regulus, but the Soviets were close behind. Like the Americans, their program began with captured V-1s, but they soon developed new designs of their own. Several missiles were prototyped, but in 1957, the decision was made to concentrate on a single model. This missile, the P-5, known to NATO as the SS-N-3 Shaddock, had several advantages over other missiles. It was supersonic, with a speed of Mach 1.2, and had a range of 300 nautical miles, but most importantly, its wings extended after launch, allowing it to be fired directly from its canister. This capability, which Regulus and most other contemporary cruise missiles lacked, allowed it to be launched much more quickly, and without sending personnel topside. The first could be launched after about 5 minutes on the surface, with others following at 10-second intervals.

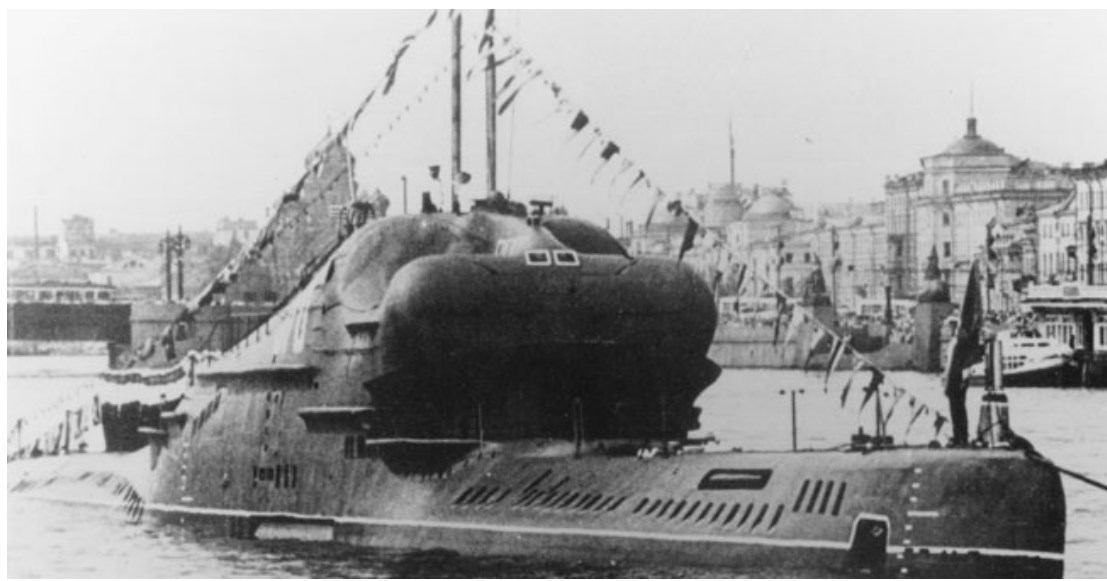

A Whiskey Long Bin submarine

The P-5 first went to sea in 1960 aboard a quartet of modified Whiskey class diesel attack submarines, each fitted with a pair of canisters aft of the sail. These boats, known to NATO as Whiskey Twin Cylinder, were followed over the next few years by six new-build Whiskeys, known as Long Bins, stretched and fitted with four fixed tubes in an enlarged sail. Unlike the American diesel boats, these didn't undertake long-range patrols. They were followed by purpose-built nuclear-powered missile submarines, known to NATO as the Echo I class. However, P-5's days were numbered. The Soviets, always paranoid about revolt, were never particularly happy with forward deployment of strategic nuclear weapons. By the time it entered service, ICBMs, which were far easier to control, were becoming operational, and the Soviets chose to prioritize those instead. The investment in missile submarines was salvaged by the P-6, a Shaddock with a different guidance system for the anti-shipping role. Some of these were fitted with nuclear warheads, but a more detailed examination will have to wait for a look at nuclear anti-ship weapons. The P-6 required new guidance electronics, which were fitted to several surface ships, as well as Echo II and diesel-powered Juliett class submarines. The Echo Is were never refitted, and spent most of their careers as attack submarines, while it's unclear what happened with the Shaddock Whiskeys.

Regulus II aboard Grayback

The arrival of ballistic missiles also killed off American programs for Regulus successors. The first plan for a follow-on missile had been the supersonic Rigel, but problems with its ramjet led to cancellation in 1953. Instead, work began on Regulus II, which would offer a range of 1,200 miles, a speed of Mach 2, and an improved guidance system that allowed it to operate autonomously. This obviously meant a larger missile, but Grayback and Growler were both designed to carry two of them, while Halibut could handle four, as could a planned class of SSGNs, which would house each missile in an individual hangar to reduce the risk of flooding. Plans were also made to fit Regulus II to a number of cruisers, and the possibility of air launch from a P6M Seamaster was also discussed. The testing program went reasonably well, with Grayback carrying out a launch in 1958, but that December, the program was axed. By this point, the Polaris program was well underway, and the new ballistic missile seemed to fill the same niche as Regulus, but at a lower cost. A year earlier, the third-generation Triton had also been killed. It had been planned to make as much as Mach 3, with 50% more range than Regulus II, but no hardware had been built before the whole thing was called off.

A Tomahawk, launched from one of its early platforms

But ballistic missiles wouldn't kill off seaborne cruise missiles forever. The Soviets retained secondary land-attack modes in their anti-ship cruise missiles, and the concept returned in the 1970s, when the US realized that a loophole in the SALT treaty allowed for ship-launched cruise missiles. Advances in technology meant that the resulting weapon could be launched while the submarine remained submerged, navigate with impressive accuracy purely on its own, and be fired from a standard 21" torpedo tube. It was known as Tomahawk, and a surface-launched version quickly followed, frustrating the Soviet attempts to track US nuclear strike platforms, and spawning a conventionally-armed variant that has become a mainstay of the USN's arsenal.

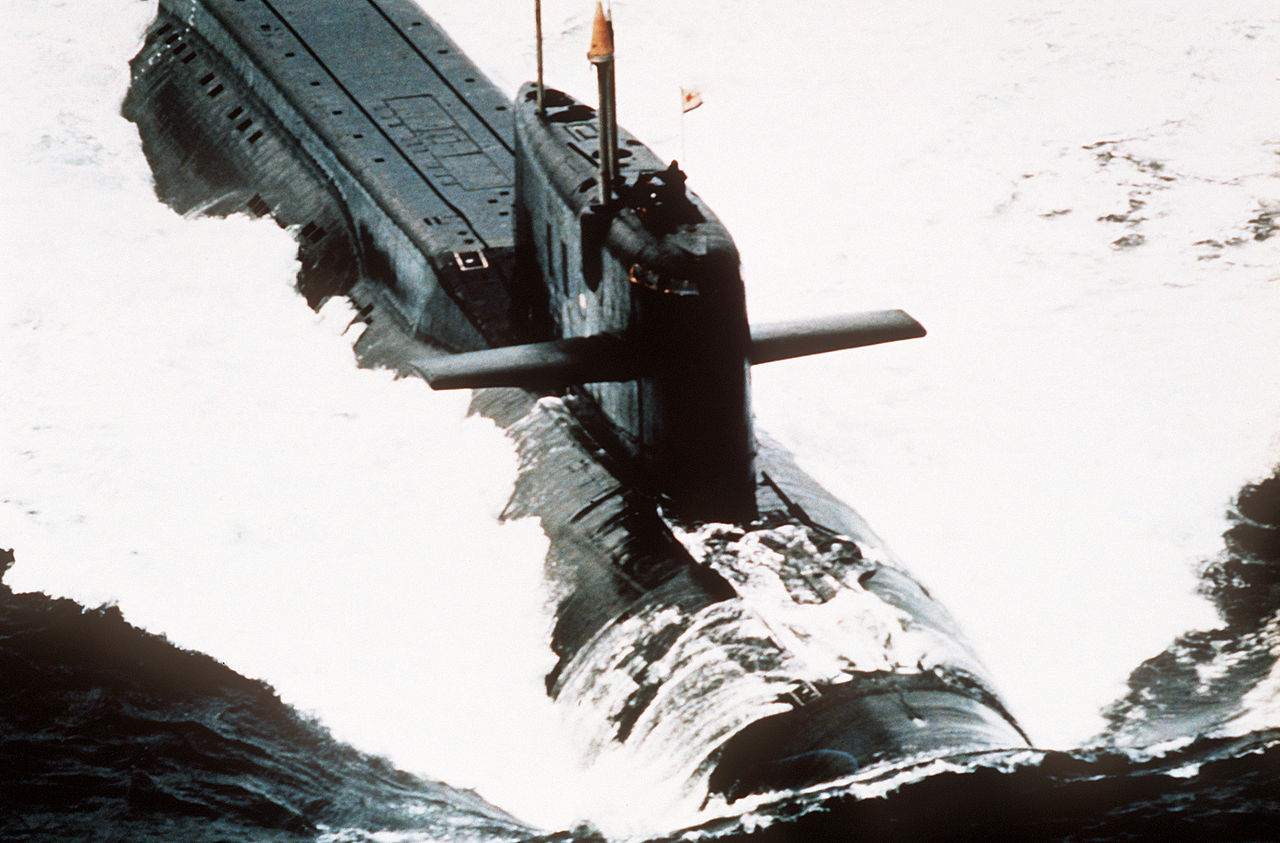

The Yankee Notch submarine on the surface

The Soviets also realized that this was a good idea, and quickly moved to copy it, producing the RK-55, NATO reporting name Sampson, and also known as "Tomahawkski" for its resemblance to that weapon. In addition to fitting the new missile to their attack submarines, the Soviets rebuilt an old Yankee class ballistic missile submarine to "Yankee Notch" configuration, replacing the missile compartment with a new section that had 12 tubes for RK-55s and storage for up to 40 of the missiles. A land-based version was also developed, again paralleling Tomahawk, but it wasn't deployed due to the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty. At least not until 2014, when the Russians finally put it into service.

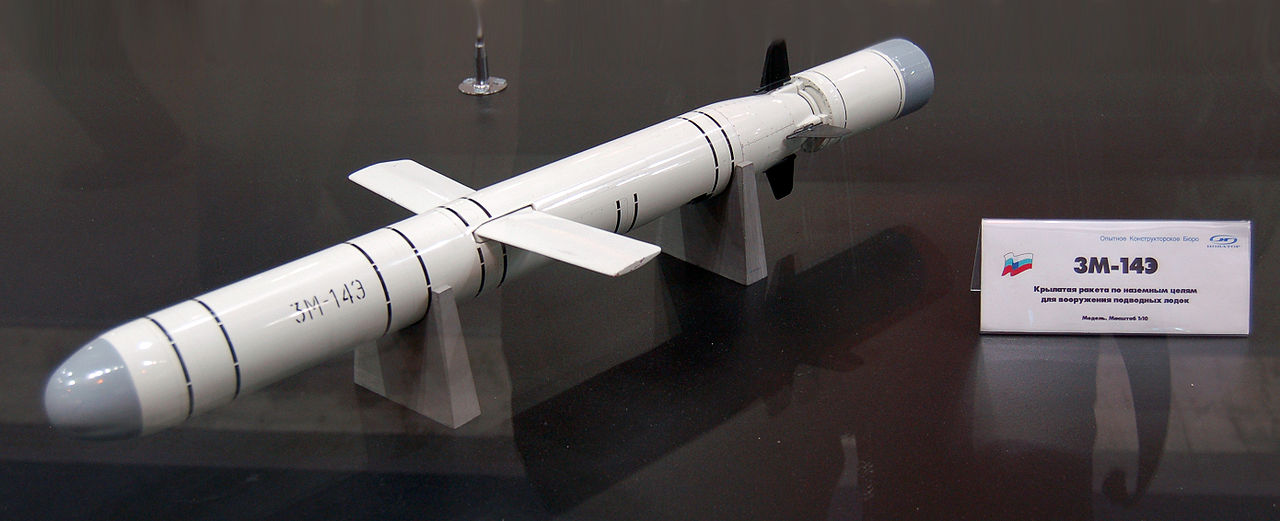

Kalibr missile

The RK-55 was followed into service by the 3M-54 Kalibr, which includes versions for both anti-ship and land attack missions. The Kalibr family attempts to combine the benefits of subsonic (size and weight) and supersonic (penetration) flight, by using a rocket booster to take it from its subsonic cruise to around Mach 3 as it nears the target. It's not clear how many of the land-attack versions have this capability, but it's definitely an interesting weapon. The Russians also developed a properly supersonic cruise missile, the Kh-80, and converted another Yankee into a test platform. However, it was cancelled in 1991, when an agreement was reached to remove all nuclear-tipped cruise missiles from forces afloat. The US finally scrapped the TLAM-Ns during the Obama Administration, but noises have been made about them coming back. The Russians probably still have theirs in their stockpiles, although it's impossible to know for sure.

An Echo II fires a Shaddock

But despite their resurgence, cruise missiles ultimately remain a sideshow, and the bulk of seaborne nuclear power since the 60s has been provided by ballistic missile submarines. We'll pick up their story next time.

Comments

You forgot the Whiskey Single Cylinder.

I did not. Whiskey Single Cylinder was just the test platform, not an operational one, and as such, I deliberately left it out.

Wow. That Whiskey Long Bin is one u-ugly submarine.

The profile view of the Whiskey Long Bin doesn't look that bad. It looks like a large World War 2 style submarine hull with the sort of streamlined sail you'd find on later boats.

It definitely looks better from some angles than from others, and yes, I did deliberately choose a picture that was not from a flattering angle. I've actually seen one or two that were even worse, but they weren't ones I could use here.