In my journey through my pictures from Iowa, I've previously looked at the quarters of the officers, and those of the enlisted men. But I haven't taken a careful look at the mess facilities, an omission I intend to rectify. This includes food prep, serving and eating, which I will deal with in turn. I've taken a closer look at the food itself elsewhere.

First, food prep facilities. Feeding a crew of 1,500, as were assigned in the 80s, took a lot of work,2 and Iowa had 65 full-time mess management specialists, reinforced by 77 men from other departments on a rotating basis. Unfortunately, while I've been to the refrigerated storage lockers, it was long before this blog began, so I don't have pictures.3

A smaller kitchen on the port side, which I believe supported the fast food mess line.

A special room is set aside for the preparation of fruits, vegetables, and meat. The crew consumed 230 lbs of fresh fruit daily.

The bakery was tasked with preparing the almost 14,000 slices of bread and 7,000 rolls the crew consumed daily

Slicers to cut up the loaves

And the bread cooling room, which is definitely a thing

The main kitchen has a number of facilities for feeding the crew

The kitchen prepared the lion's share of the 1,500 lbs of meat, 1,900 pounds of potatoes, 4,320 eggs, and 400 lbs of vegetables that were served aboard each day.4

Tools included a deep fryer...

and several giant steam kettles, also useful if we need to boil oil to pour on boarders.

Sailors looking for food were faced with a choice. They could go down the starboard mess line, which served traditional fare, or down the fast food line to port, which always had food like hamburgers. The two lines wrapped around the barbette for Turret 3, and joined up on the mess deck proper. Four meals were served daily: breakfast, lunch, dinner, and mid-rats, a meal for those who had overnight watches.

The starboard mess line

The port mess line

Looking from behind the port mess line.

The milk machine. 250 gallons were consumed daily.

The ice machine. No idea how much was used every day.

Then it's to the mess decks to eat. Originally, these were fairly standard tables, but in the 80s, they were replaced with table-and-chair combs that wouldn't look out of place in a fast-food restaurant. One specific fast food restaurant, actually, although I'm pretty sure that neither the Navy nor the Pacific Battleship Center stole the tables from them. There were originally two mess decks, although the aft one has been converted into the museum and gift shop.

The forward mess deck

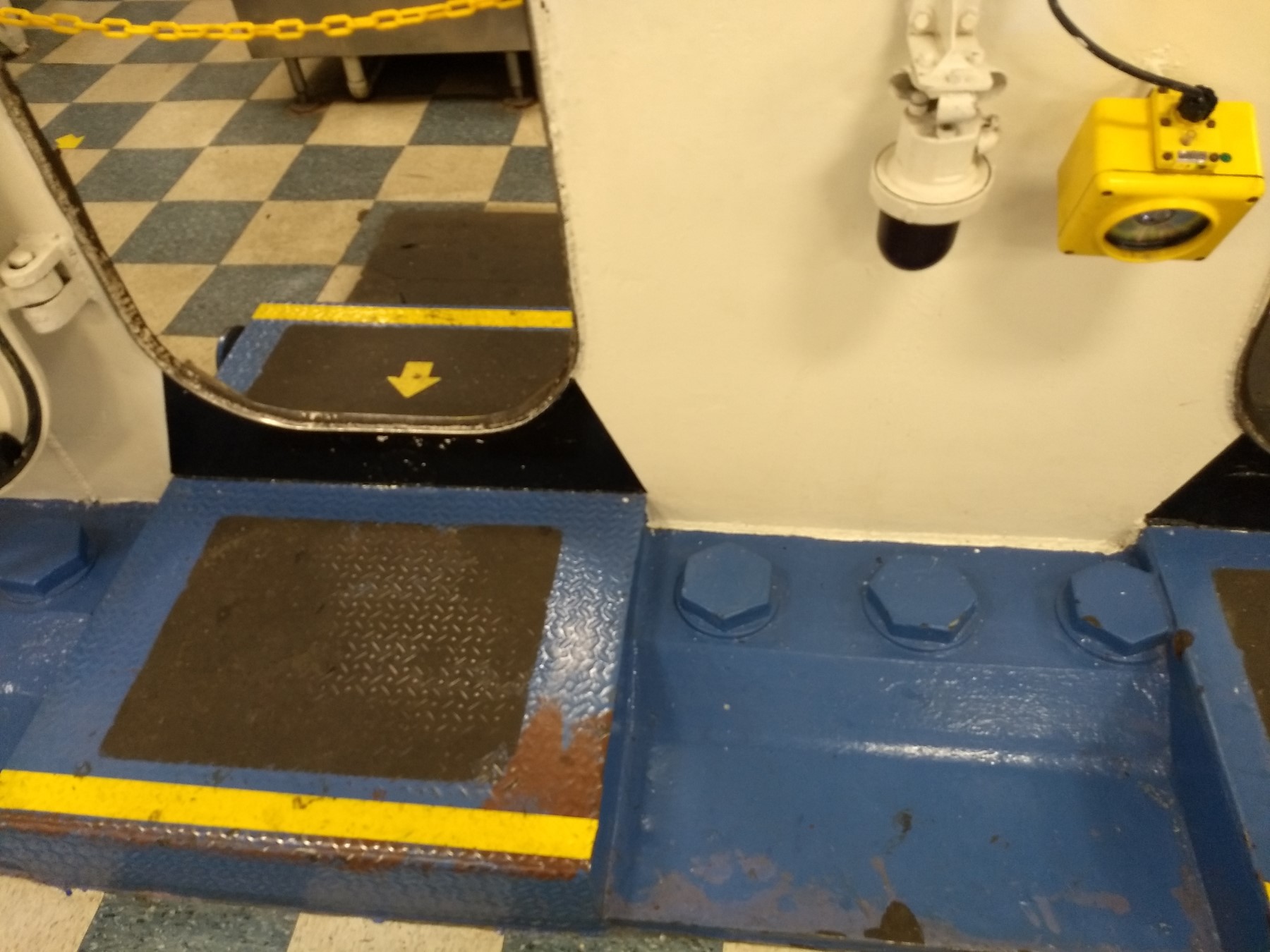

The mess decks are the first compartment aft of the aft end of the citadel, and you can see the very impressive bolts that secure the armored deck.

Once a sailor was done eating, he'd take his dishes back to the scullery. This still survives, tucked away into a corner of the gift shop.

The scullery

Dirty dishes go in one end of the machine

And clean dishes come out the other

One of the ship's two stores was also near the mess decks. Known as the "gedunk", it sold various snacks when the mess lines were closed. Today, it's part of the gift shop.

An enlisted man's life wasn't limited to just the mess decks and his berthing comparments. He also had a number of amenities to make his life better, and we'll take a look at these, mostly located on the third deck aft, next time.

1 The exhibit had been upgraded with manikins and better display food since most of the photos shown here were taken in 2018. All photos from my collection except where otherwise noted. ⇑

2 It was even more work in WWII, when there were a thousand extra men aboard. In that era, they consumed 7 tons of food per day costing $1,600, ($20,452 in 2012 dollars). Of the seven tons, 1 ½ tons were fresh foods, 2 tons were frozen and 3 ½ tons dry. In addition, the soda fountain produced 9,600 gallons of ice cream each month. ⇑

3 These could hold 100 tons of fresh fruit and vegetables and 84 tons of frozen meat. Iowa could also carry 650 tons of dry stores, which gave her 119 days worth of food with her WWII crew. ⇑

4 Some food was prepared in the officer's pantry, or for the Chiefs in the Goat Locker. ⇑

Comments

Speaking of gedunks...

On the USS New Jersey in WW2, a couple of new ensigns decided that 'rank hath its privileges' and decided to cut ahead in the LONG line of sailors waiting to get ice cream. There was a lot of quiet grumbling by the enlisted but want can you do? These were officers.

Well a loud, gravely voice was soon heard telling the ensigns to "Get your ass back in line!" along with a few other choice insults. The ensigns turned to reprimand that insolent enlisted man and found they were were face to face with Admiral Halsey! Who was waiting patiently in line with the rest of the crew.

The ensigns went back to the end of the line and the story spread like wildfire on the ship then the fleet.

re. footnote 4, was most of the officers' food from the main kitchens, with their pantry for sprucing up wardroom meals on special occasions? Or did they have better food generally?

Were men sent to meals in shifts, or was it a free-for-all for everyone off duty at the time?

I wonder what the backup plans were for dealing with battle damage; it looks like a single unlucky hit could make it hard to keep everyone fed on the rush back to Hawaii.

@MT echos

Interesting. I hadn't heard that story.

@echo

AIUI, the officers ate primarily out of their own pantry. They did have better food, but they also had to pay for it out of their own pockets. Old naval tradition, dating back to the age of sail.

Again, AIUI (and this is really not my area of expertise) it was pretty much a free-for-all. The meals were scheduled so that they straddled the change of the watch, so everybody had a chance to eat.

As for the backup plan, there were at least two other food prep spaces, and if worst comes to worst, everyone eats sandwiches until they get back. It was pretty common for other ships to send over hot food in cases like that.

This is great, but the pictures are all (duh!) in the 80s config, and I'm guessing the food (both prep techniques and choices) were pretty different in WW2; do you have much if any info about it?

I have a little bit in my library, but it's rather scattered and low on details. I do know there are lots of slice-of-life pictures of Missouri on her shakedown cruise floating around. Navsource and wikimedia should both have them.

Meals are served as a free-for-all timed across watches (and with temporary chow reliefs for nonstandard watches that span mealtimes) on ships today, for what that's worth, though it somewhat depends on the ship. Carriers and LHDs, for example, have very extended chow hours to accommodate their large crews, but even on a destroyer, the CSes would keep the lines open longer if needed.

Steam kettles? So the kettles, and maybe the rest of the facilities were heated by piped steam and not little gas burners or electrics?

Were these fed from the propulsion boiler systems?

Yes, they were heated by steam. Definitely not gas (really dangerous on a warship for obvious reasons) and I guess steam was easier and better-proved than electricity, which they use today. As for where the steam came from, it's auxiliary steam. 600 psi steam is really dangerous stuff, and for stuff like cooking and heating, ships would use auxiliary steam at 150 psi. They'd take off 600 lb steam before it went through the superheater, and most of that would go to things like the turbogenerators (I think) and other auxiliaries. Some was reduced to 150 psi for heating (and the whistle).

Is that saturated dry steam (i.e. ~180°C) or superheated?

I'm not certain. It appears that it's 600 psi saturated auxiliary steam, dried and passed through a reduction valve to 150 psi. I suspect (though I'm not sure) that this will give it some degree of superheat, but I have a book at home that will likely have the answer.

I think you've addressed this before, but how evenly loaded are the watches in terms of staffing? For some things, like engineering or navigation, I imagine it was pretty evenly loaded, as the ship was operating 24x7, but for non-redundant/24x7 roles (i.e. I think each gun only had a single crew), were they mostly staffed to daylight watches, or was that somehow evened out as well?

I'm not really sure how that worked. Things like the guns aren't going to be fully manned except when they're specifically needed. They definitely don't send all the gun crews to their stations to just sit for a couple of hours as a routine practice, although in hostile waters, some stations may be manned 24/7 to keep response time down. (For instance, Iowa might have manned 4 of the 5" turrets constantly so they could engage any aircraft that took them by surprise.)

But as for what a gunner's mate's life looked like during peacetime, I'm really not sure. It's quite possible that they were "on watch", but basically used the time for maintenance and training. Unfortunately, my contacts are heavily on the snipe side of things, but I'll have a look around my books when I get home.