The Yangtze River is one of the world's great riverine highways. Even without modern navigational improvements, it was navigable from its mouth at Shanghai up through Hankow, 600 miles inland, even by smaller ocean-going ships of 5,000 or 6,000 tons. Above Hankow, the river narrowed and shifting sand-banks made navigation difficult, but there were no serious obstacles below Ichang, 1000 miles inland. Above Ichang were the gorges of the Yangtze, a treacherous area with many rapids that were usually overcome by the sheer muscle power of hundreds or thousands of coolies hauling junks and steamers through them. Foreign steamers rarely reached beyond Chungking in Sichuan Province, 300 miles above Ichang. The great fluctuations in the river level, up to 100' between winter low water and spring flood in places, made navigation even more difficult.

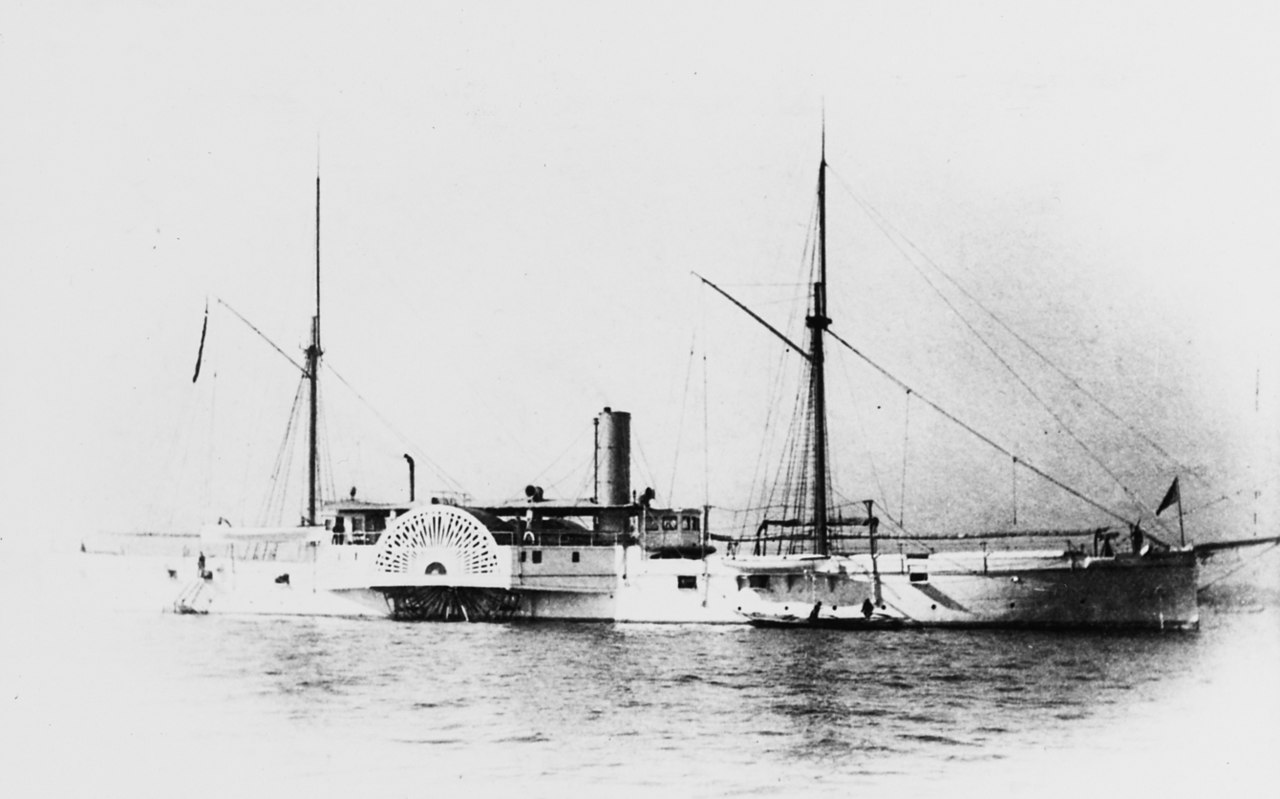

USS Ashuelot, an early Yangtze gunboat

In the 1860s, this great artery was opened to foreign traders, who quickly established settlements in the major cities. The unequal treaties that had opened China gave the Western powers the right to police their own citizens, as well as exemption from most taxes. But even if the Qing government had wanted to enforce said treaties, it was too weak to do so effectively in the vast interior of China. Bandits and warlords ran rampant. To make matters worse, the Qing didn't really want to enforce the treaties, and would much prefer to be able to tax the fan-kui,1 or at least see them suffer. The fan-kui weren't particularly popular with the general population either, and the local authorities were often sluggish in dealing with mobs that threatened missionary or merchant property. Obviously, the major powers would have to see to their own protection.

The solution to this problem was gunboats. With the exception of missionaries, who tended to have rather mixed feelings about other outsiders, Westerners rarely ventured far from the Yangtze and its immediate tributaries. A gunboat was naval power in a small package, capable of seeking out trouble spots and providing power both overt and discreet afloat and ashore.2

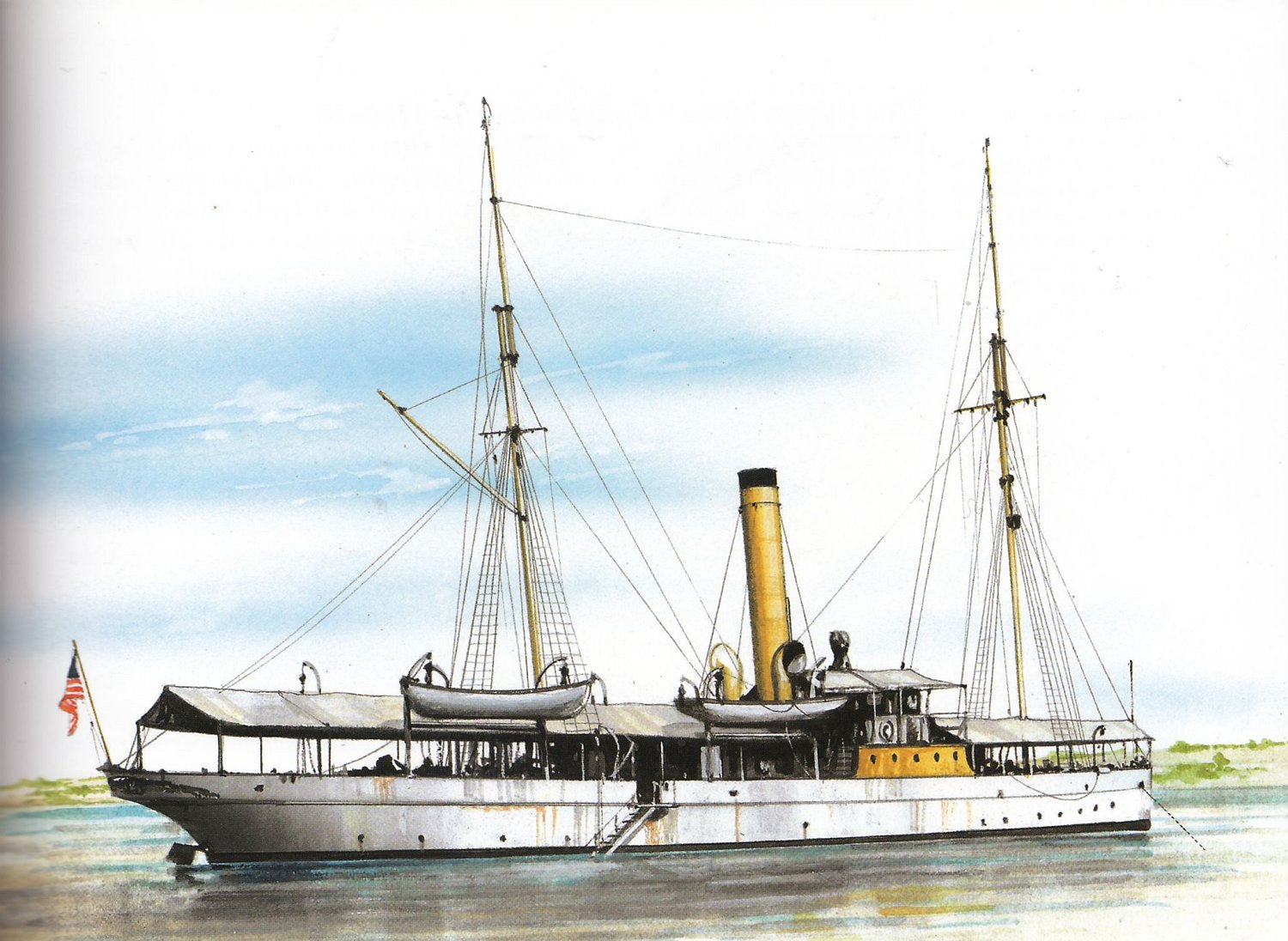

Villalobos, one of the gunboats captured from the Spanish

Initially, these boats a were ragtag bunch of castoffs, most originally intended for other tasks.3 But they did sterling work in late Imperial China, carrying out missions ranging from discouraging bandits who tried to set up "toll booths" on the river to retaking ships captured by pirates to sending ashore landing parties when mobs threatened Western settlements. When things were calm, they would show and protect the flag, making sure that the Chinese didn't get ideas about how much control they had in what was nominally their country. The fall of the Qing government in 1911 didn't change much, except to end any fiction of the central government's control in the hinterlands. Pirates and bandits became more frequent, as did clashes between them and the gunboat crews. Fortunately, most bandits were armed only with rifles, which they shot very poorly, and machine-gun fire plus a few shells from heavier guns were enough to disperse them.

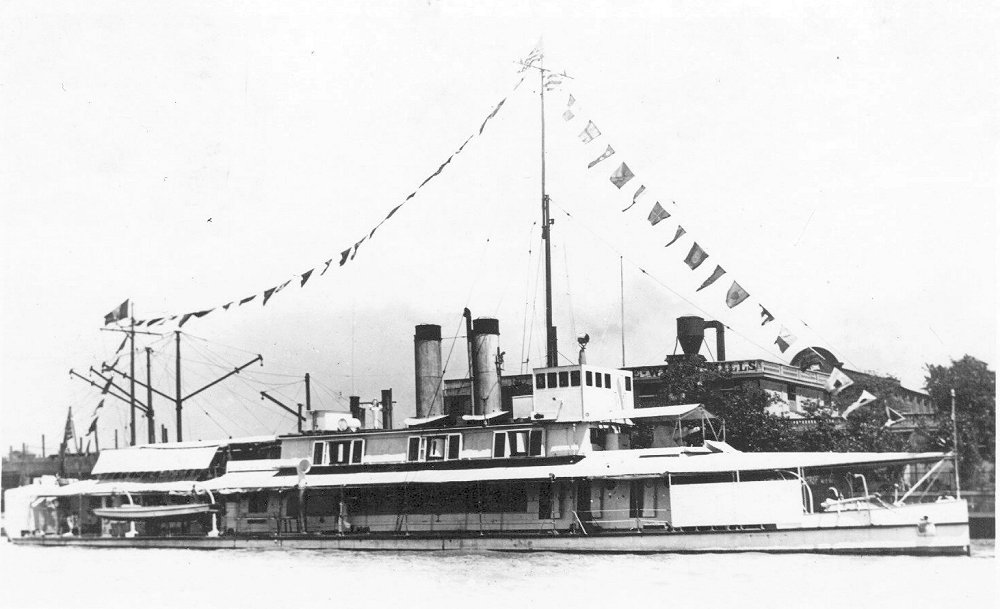

USS Monocacy

WWI brought most operations on the Yangtze to a temporary halt, as the Chinese remained neutral until after the Americans joined the war, and they insisted that the gunboats of hostile powers cease operations. The 1920s brought more upheaval in China, as the warlords continued to fight for control of the country. Gunboats often had to intervene to make sure that their armies didn't threaten the interests of their merchants. During one battle, an officer from an American gunboat went ashore to make sure that an artillery battery didn't fire too close to Standard Oil's local compound. Banditry continued to grow worse, and merchant steamers often had to be provided with armed guards. By the mid-20s, nationalism had become a serious force in China, merging with the traditional hatred of the fan-kui to make things seriously difficult for the foreign merchants and the gunboats that protected them.

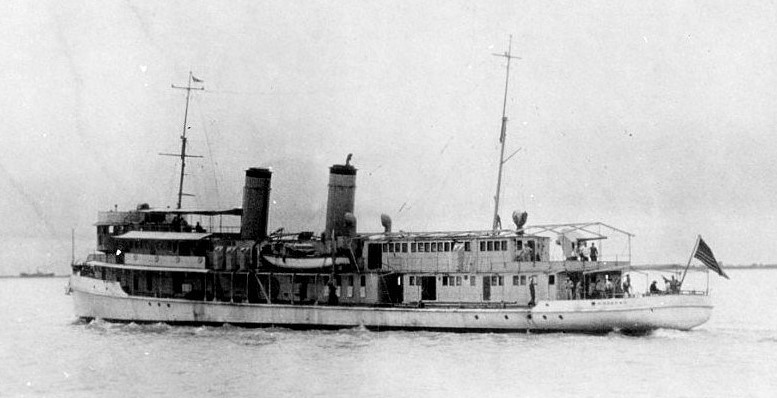

Gunboat HMS Bee, sister of Cockchafer

The first major incident took place in 1926, when one of the warlords attempted to commandeer the British-owned steamer Wanhsien, but were dissuaded by the captain of the gunboat HMS Cockchafer.4 A second attempt at commandeering steamers resulted in the capsize of sampans and the apparent loss of the Army's payroll, leading to Wanhsien and her sister Wantung being captured by the warlord's troops. Negotiations proved fruitless, and the British decided to rescue the ships and their crews, still trapped aboard,5 by force. A great deal of force was needed, and when the dust cleared, the crews had been rescued, but the steamers were still in Chinese hands, seven RN personnel were dead along with dozens of Chinese, and a significant part of the city of Wanhsien had been destroyed.

HMS Vindictive

Things went from bad to worse when Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists launched their Northern Expedition, quickly spreading from Canton to reunify the country. They were fervently anti-Western, and when they approached Nanking, a major port on the lower Yangtze, many of the local Westerners were evacuated. However, Nanking was the center of the American missionary effort in China, and a number of them remained behind, along with the British and American consuls. When the Nationalist Army finally took Nanking, they quickly began to loot the city and kill a number of foreigners. A landing party was sent ashore, and a force of foreign warships, led by the British heavy cruiser Vindictive and including a number of American destroyers, covered the evacuation with their guns.

USS Mindanao

Over the next month, the nationalists raced down the Yangtze, closing on Shanghai, the heart of the international community in China. The foreign powers poured troops into the city, while gunboats and larger ships stood by to provide firepower. Communists and union organizers teemed in Shanghai, but before the war broke out, Chiang ordered a purge of communists from within the Nationalists, kicking off the war that would define China for the next two decades, and dominate the rest of the Yangtze Patrol's life. We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 Usually translated "foreign devils", which pretty much sums up the Chinese attitude towards the Western powers. ⇑

2 While this part and the next one will focus on the Yangtze, this shouldn't be taken to mean there weren't gunboats elsewhere in China, most notably on the Pearl River (Hong Kong/Canton) and its tributaries. However, I have little information on these ships, and have chosen to ignore them for now. ⇑

3 The backbone of the American Yangtze Patrol until the late 20s was a motley flotilla of ex-Spanish gunboats captured or bought after Manila Bay. ⇑

4 Yes, this was an actual gunboat, named after a rather bizarre-looking beetle. ⇑

5 At this point, banditry was so common on the Yangtze that steamers had steel armor around the areas occupied by the Western crew. ⇑

Comments

Wow, this sheds a surprising amount of light on modern China's military posture

Read or watch The Sand Pebbles for a fictional view of gunboats in China in this time period. Plus, Steve McQueen!