The Yangtze is one of the world's great riverine highways, and when western powers began to intervene in China during the 19th century, it was a vital avenue for their commerce as well. However, China was not particularly cooperative in defending western rights under the "unequal treaties", and so the western powers had to find some means of doing it themselves. Gunboats were the obvious answer: self-supporting, mobile, and able to bring a great deal of firepower to bear. The Yangtze Patrol fought bandits, protected westerners from mobs, and generally made itself useful from the late 1800s onward. Things began to heat up with the rise of the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek in the 20s, and the beginning of the Civil War between his forces and the Communists in 1927.

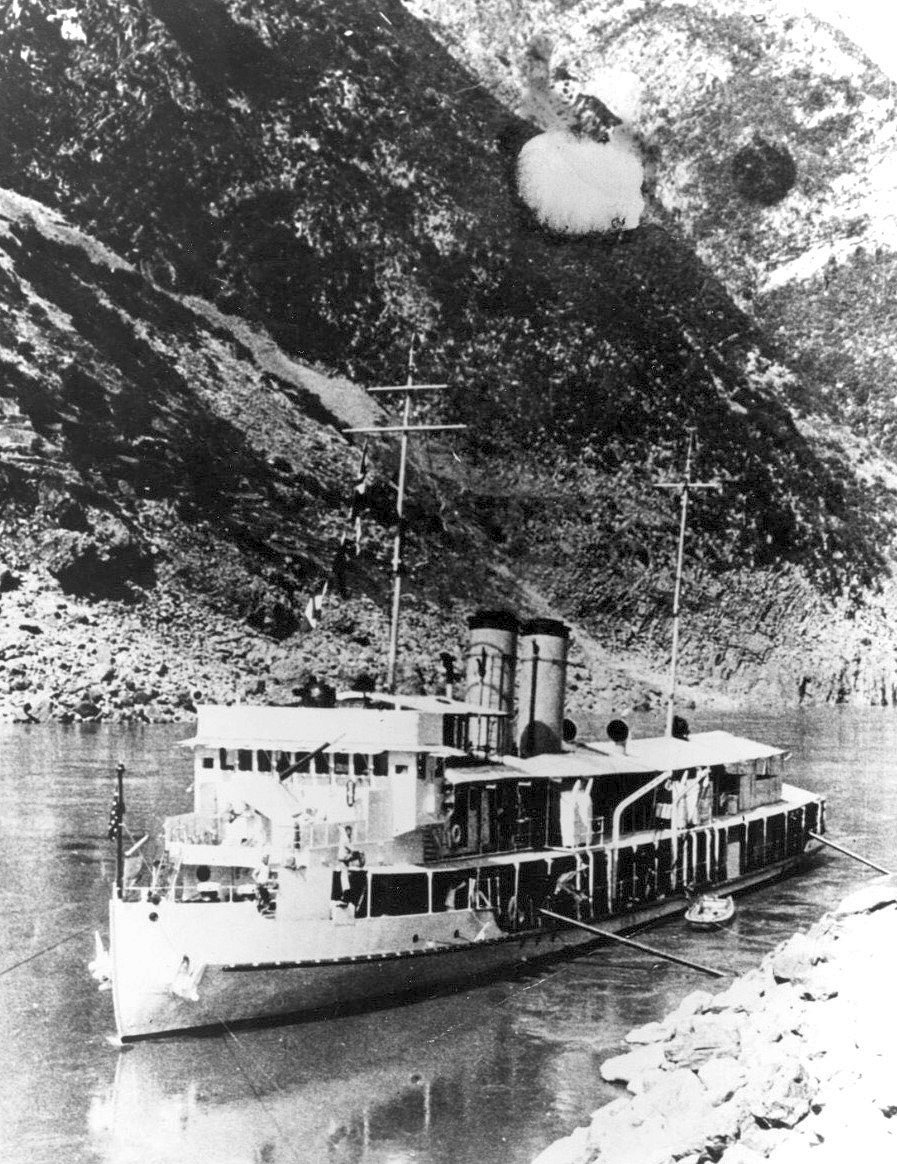

Gunboat Oahu on the Yangtze

The Yangtze was a unique duty station for the men assigned there. They served on tiny ships, often ill-supported and isolated in a strange country. Some gunboats were so crowded that a portion of the crew had to sleep on deck in all conditions. But there were also advantages. Except at the height of the depression, the exchange rate greatly favored the gunboat sailors. Onboard ship, chores were done by hired Chinese boatmen, while ashore in Shanghai, a sailor's pay could buy him excellent entertainment in the form of alcohol and companionship, usually provided by one of the white Russian exiles that teemed in the city. Officers could participate in the social life of the western communities up and down the river: clubs, hunting, horse racing and generally having a good time.

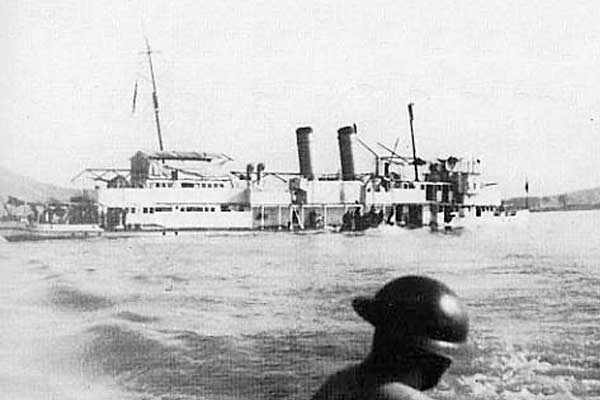

Sailors from Oahu armed for guard duty

The activities required of the gunboats on-duty were no more regular. A day on the Yangtze could involve anything from the regular clashes with bandits to keeping looters away from a stranded steamer while she was salvaged to providing muscle for an attempt to ransom a kidnapped westerner. Improvisation was the order of the day. One captain developed a novel technique when faced with exceptionally shallow water. A member of his crew was given red underwear and told to wade ahead of the gunboat. So long as the underwear was not visible, the gunboat went ahead slowly, and if it emerged from the water, a crash stop was made. Gunboat crews also found ways to employ their guns against the local wildlife, filling them with birdshot and black powder to turn them into giant shotguns. This did tend to damage the barrel, and one British gunboat crew, facing an inspection, came up with a brilliant workaround. The inspecting officer was shown the unmarred aft gun, then taken to the wardroom for a very long and entertaining lunch. When he finally got around to looking at the forward gun, he found it in equally good condition, as the crew had switched the guns while he was eating. On another occasion, an American gunboat had to convene a court-martial, and found that all three of their officers had duties as officers of the court, leaving nobody to serve as defense counsel. An officer from a British gunboat volunteered, and his services were accepted after a thorough check of the manuals showed no prohibition against such a procedure. This caused more than a little heartburn in Washington when word got back to them, along with a swift change in the relevant directives to prevent a recurrence.

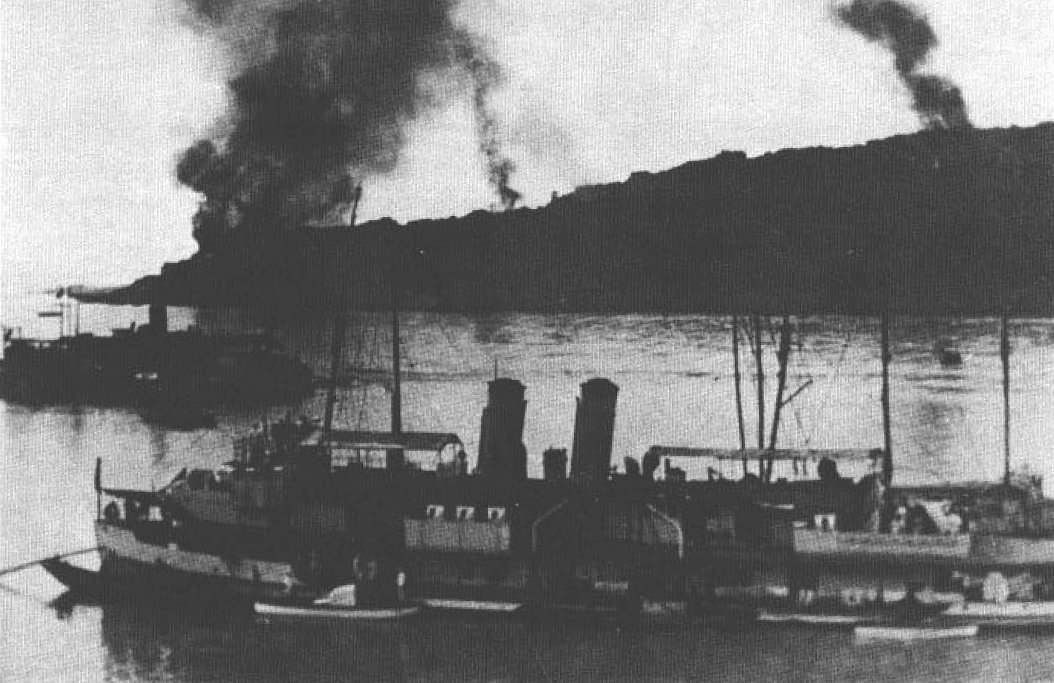

Luzon aground somewhere on the Yangtze. She was refloated successfully.

In the 1930s, Japanese avarice towards China, quiescent since the Sino-Japanese War, began to stir. In 1932, the Japanese attacked Shanghai, sparking a battle that ended with a ceasefire prohibiting the Chinese from stationing troops in their own city. Five years later, the Japanese finally began their invasion of China, starting again with Shanghai. The fighting was fierce, and the men of the Asiatic squadrons often found shells landing nearby and bombs falling around them. The last was often the result of Chinese pilots, who were not very good at identifying ships, attempting to attack Japanese vessels who were supporting their troops ashore. Finally, the Chinese were forced back, and the Japanese began to advance up the Yangtze on Nanking, the capital of the Nationalist Regime.

Panay sinking

As they closed in, the remaining Americans in Nanking began a recreation of their evacuation a decade earlier, in several ships escorted by the gunboat Panay. Previously, river traffic had been spared attack for fear of hitting neutrals, but a Japanese naval squadron operating nearby received "confirmed reports" of a group of Chinese troopships heading upriver. They found Panay and her consorts anchored above Nanking, and immediately attacked, ignoring the American flags painted on her awnings.1 The first bombs struck the ship, wounding the Captain and many of the crew and cutting an oil line to the boilers. Panay's crew fought back with machine guns, but the ship was clearly doomed, and the order to evacuate was given by one of the officers, who wrote it down because of a wound to his throat. Ultimately, 3 men were killed, the first American dead of WWII. 43 more were wounded by either bombs or strafing, and they and the other survivors spent a harrowing few days in the countryside, afraid that the Japanese would hunt them down to finish the job, before the British evacuated them. Two newsreel cameramen were aboard the ship at the time of the attack, and their footage did a great deal to turn American opinion against Japan.

The next Japanese target was Wuhan, further up the Yangtze, the second-largest city in China and the new capital of the Nationalist regime. Their initial plan was to attack from the north, but the Chinese thwarted this with a bit of riverine warfare more literal than most, breaching the dykes of the Yellow River. Chiang's plan to "use water as a substitute for soldiers" thwarted the Japanese, but also killed half a million of his people and rendered several million homeless. The Japanese turned their attention to an advance up the Yangtze, supported by forces afloat. More important than the firepower their ships could bring to bear was the logistical artery provided by the river. The Japanese normally had horrible logistics, but the Yangtze allowed them to reach bare adequacy during the campaign against Wuhan. Despite this, the Chinese proved tenacious, and were only driven out after several months and extensive use of chemical weapons.

The next four years were a tense time for the Yangtze Patrol. Several gunboats, including the American Tutuila, retreated to Chungking, above the militarily-impassible Yangtze gorges, with the Nationalist government. There, she was stranded amidst heavy air raids, and forced to rely on a local tug for steam, as oil was unavailable. This produced some difficulty with the auditors, who couldn't understand why an oil-burning ship needed to buy coal, particularly in such small lots. After the outbreak of war, Tutuila was handed over to the Nationalists and her crew evacuated. She would serve Chiang's government until 1949, when she was scuttled as the Chinese Civil War wound down.

Tutuila in Chungking during a Japanese air raid

In November 1941, increasing tensions with Japan lead the Americans to withdraw most of their forces in China to the Philippines. Gunboats Luzon and Oahu departed Shanghai for Manila in late November, their first time in salt water during a 13-year career. Despite a massive typhoon, their officers and men made it to the relative safety of the Philippines, and on December 5th, the Yangtze Patrol was formally dissolved. Both ships provided inshore patrol for the defense of the Philippines over the next few months. Oahu was sunk by Japanese gunfire, while Luzon was scuttled. Left behind was Wake, intended to provide communications services to the American Consul. The Japanese managed to surprise the crew and forced them to surrender the ship intact, the only American vessel to do so during WWII. Luzon was also salvaged, a common practice for riverine vessels which were usually sunk in shallow water, and taken into Japanese service. Luzon was converted into a submarine chaser, and later torpedoed by the submarine Narwhal. The damage was too extensive to repair, and she was scuttled near Manila to block a channel. Wake's wartime career was undistinguished, but she survived to be recaptured by the US, handed over to the Chinese Nationalists, and then captured by the Communists, who kept her in service for at least another decade.2

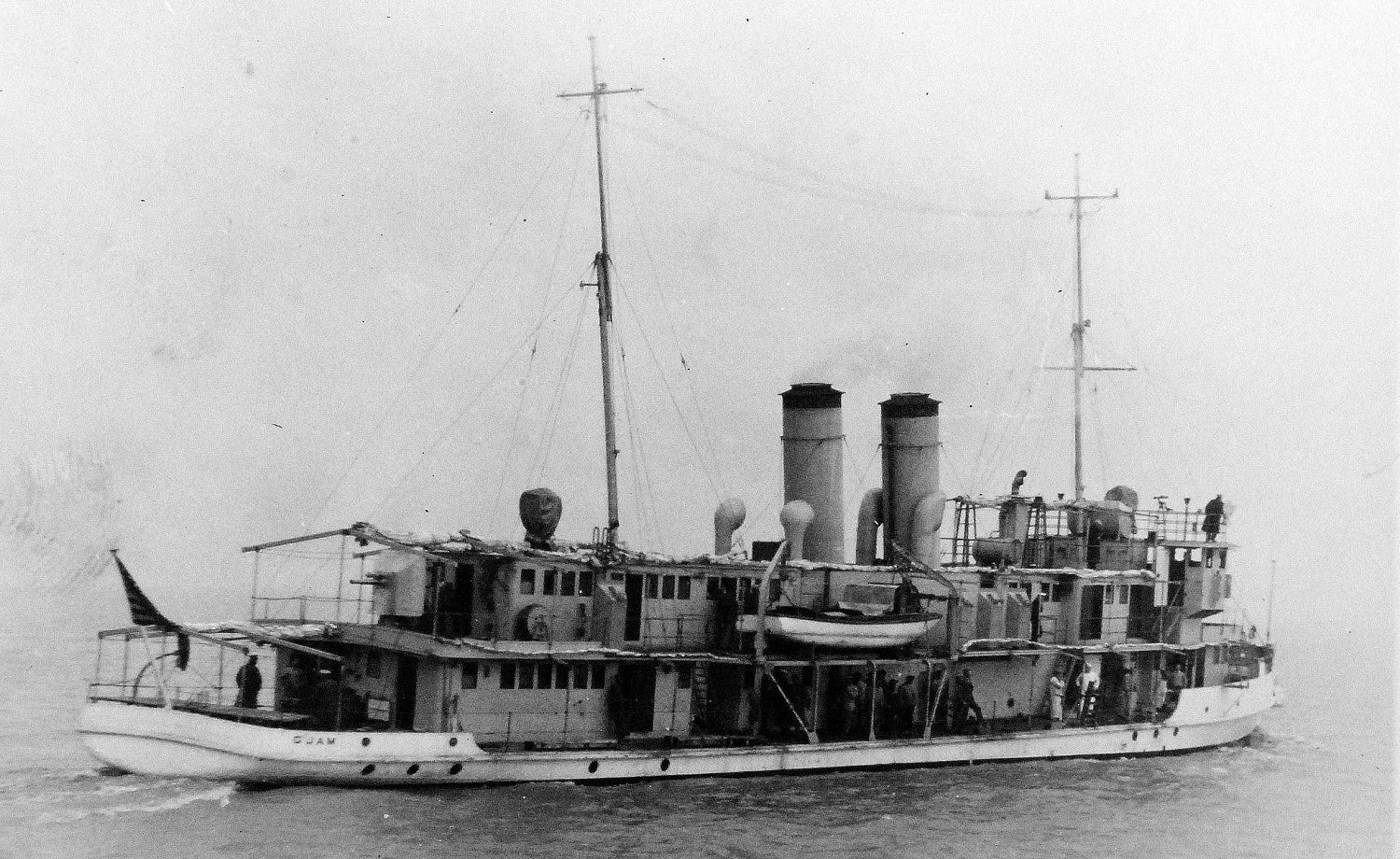

Guam, later Wake, on trials

The war utterly destroyed the traditional pattern of foreign trade in China, and with it the rationale for the gunboat force. Foreign warships did again see the Yangtze in the turbulent months after the war, primarily to aid in picking up the pieces left by the Japanese occupation. Even these were swiftly withdrawn, with the exception of a few vessels to support diplomats in the still-troubled country. The most notable was the British frigate Amethyst, which came under heavy fire from the Communists while heading upriver for service as a guardship at Nanking on April 20th, 1949. Mao's forces had finally managed to acquire some decent gunners, a lack of which had flummoxed all previous attempts to stop the lightly-armored foreign warships from their business on the river, and Amethyst was badly damaged and forced aground, with 22 of her crew killed. The British sent several ships to help, but they also ran into intense shellfire, losing another 13 men in the attempt. Even after she got afloat again, Amethyst was forced to anchor, and she and her crew were essentially held captive until July 30th, when negotiators finally managed to secure her release.

Amethyst docked at Hong Kong after her escape

By this point, the Nationalists had been all but defeated, and were forced to retreat to Taiwan, where they remain to this day. China was firmly communist, and the Yangtze was closed to outsiders. Today, things have changed. The Three Gorges Dam has made navigation to Chunking far safer and easier than it was in the days of the patrol, and foreign traders who come to China have to play by Chinese rules. We will probably never see the Yangtze Patrol or its like again.3 But riverine warfare isn't dead, and some remnants still survive in Europe and Russia.

1 It's possible that this attack was in retaliation for extensive American intelligence efforts in cooperation with the Chinese. ⇑

2 She was originally named Guam, but later the name was changed to free the name for a new cruiser. As a result, she ended up having five names and four different flags. ⇑

3 Most of the detail in this post came from Kemp Tolly's excellent book Yangtze Patrol, and I would highly recommend checking it out if you're interested in the subject. ⇑

Comments

Another great series Bean. The amount of homework you do on these segments is impressive and it certainly makes for good reading.

Great series, thanks!

HMS Amethyst also carried a cat named Simon, who is the only cat ever to have been awarded the Dickin Medal- an award for animals that have displayed "conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty" while serving with the Armed Forces or Civil Defence. In Simon's case, it was awarded for removing rats from the ship while it was trapped at anchor despite having been seriously wounded in the Chinese attack.

(The medal has also been awarded to 34 dogs, 32 pigeons and 5 horses. Royal Navy ships were banned from carrying live animals, including cats, in 1975 for reasons of rabies prevention.)

Thank you both.

I'd actually forgotten about the cat when I wrote this. An interesting story to be sure. Animal heroics are quite rare at sea compared to land.

Awesome series. I've stumbled on pieces of 1st-half-of-20th-century Chinese history before, and it's a thoroughly fascinating period that's almost completely overlooked in the West (not that they love to dwell on it in China AFAICT).

Also work pointing out that the Sino-Japanese war featured an act that gave an altogether different meaning to "Riverine Warfare"

So on the one hand, we've got crewmen in red underwear wading ahead of their gunboats on the Yangtze. Very colorful story, in several senses, and thanks for that. But then I read up a bit more on the Amethyst incident, and I get to the part where the British are all "screw this, we're sending HMS London upriver to sort this out".

That being the heavy cruiser HMS London, thirteen thousand tons and drawing twenty-one feet.

Rather different parts of the Yangtze, I guess.

To make it even worse, London wasn't able to sort it out. But yes, different parts of the Yangtze and different times.

Looking at the wiki articles for the Amethyst incident, I am surprised at the accuracy of the shore batteries when engaging London, but I suppose by that time they had a lot of practice shooting at the Amethyst. I'm actually somewhat surprised that the latter hadn't been pounded into scrap, but suppose the Communists were hoping to take it as a prize or use her as a bargaining chip.