The Russian battleship program continued to churn out ships in the early 1890s, producing ships in the pre-dreadnought mold. As with their earlier efforts, the result was a mix of good, bad, and bizarre ideas.

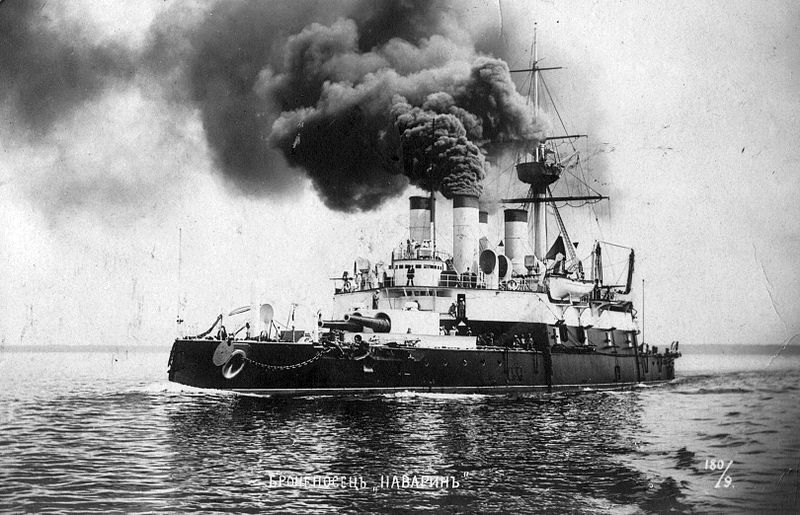

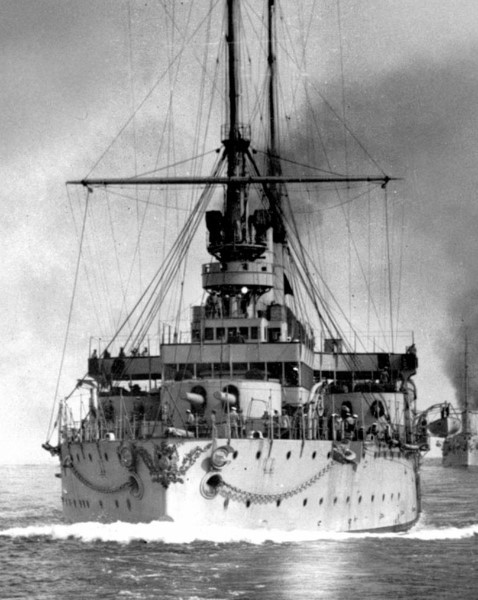

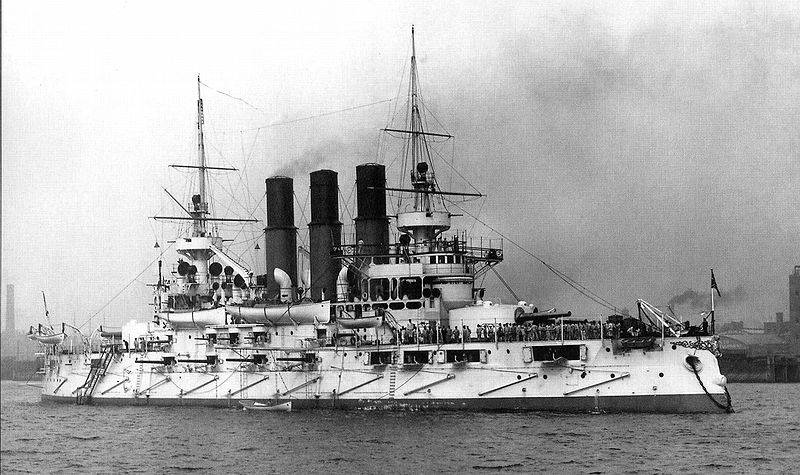

Navarin

The first Baltic battleship of this type, Navarin, was a radical departure from the previous ships. At a time when the British were shifting to high freeboard, the Russians built their first low-freeboard turret ship. Navarin was armed with a pair of twin 12" turrets and eight 6" guns, and originated as an attempt to hold down costs by building smaller ships.1 Navarin's most notable feature was her four funnels, two pairs side by side. This quickly gave her the nickname "Zavod" (factory).

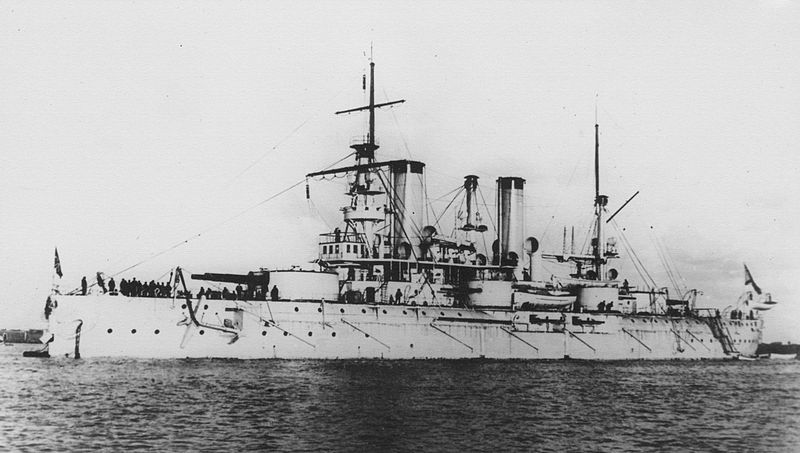

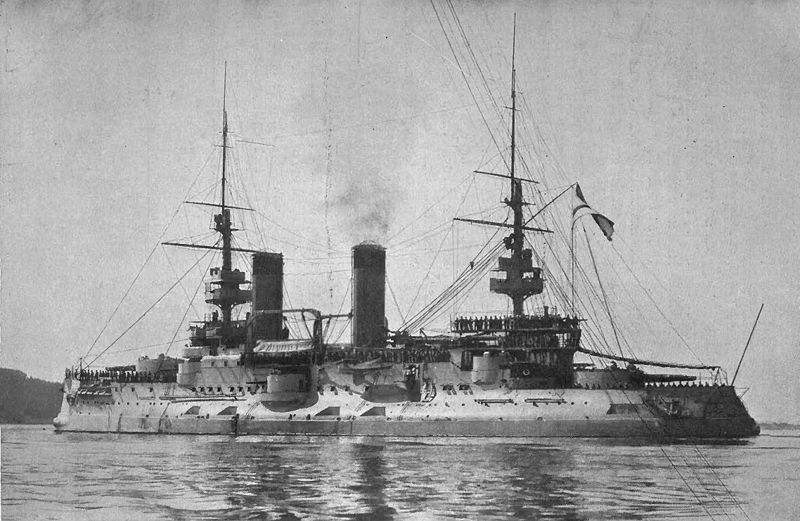

Tri Sviatitelia

The next ship built in the Black Sea, Tri Sviatitelia, was a derivative of Navarin,2 sharing largely the same layout, although not the unusual funnel arrangement. 12"/40 guns were introduced, as well as the first use of Harvey armor on a Russian battleship.

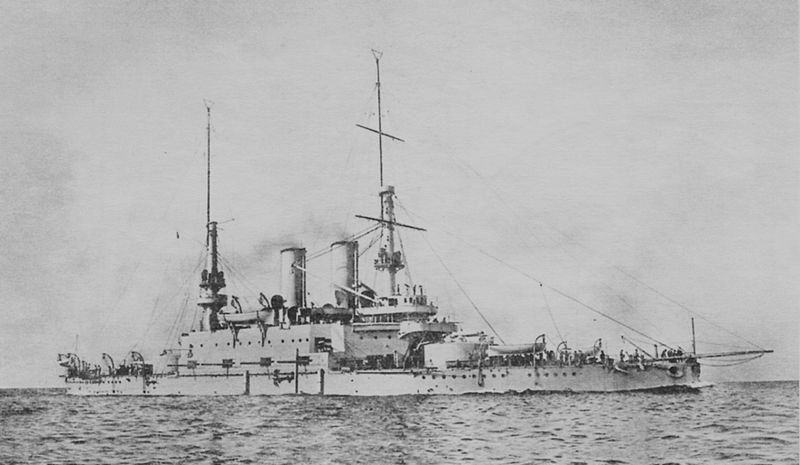

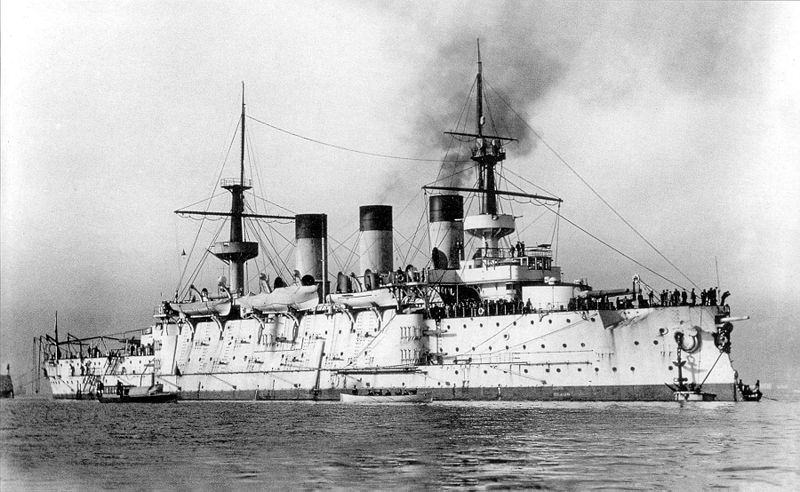

Sisoi Velikii

As the Gangut approached completion, another ship had to be laid down to keep the New Admiralty Yard busy. Senior Russian naval officers were asked for their opinions on what new ship we needed to be. The results were predictable. Some officers wanted more heavy guns, some more light guns, some less armor and more speed, and some more armor. And one Admiral wanted cruisers, and thought that the ram would still be the decisive weapon. Somehow, the Russian constructors sorted through all of this, and the resulting ship, Sisoi Velikii, another low-freeboard Navarin derivative3 was one of the most egregious examples of poor construction I've ever run across. A failure to order vital components such as the stem- and sternposts, rudder frame and propeller shaft brackets, went unnoticed for months. Design tinkering, including replacing barbette mounts with turrets, didn't help things, and the necessary drawing changes delayed the ship even further. She suffered from defective steering gear, and her trials were rushed due to international tension. Service revealed more problems, including bad seals on watertight doors and hatches, leaky gunports, and a gap an inch wide between the upper edge of the armored belt and the side of the ship.4 A turret explosion off Crete during her first cruise did nothing to help the ship's reputation.

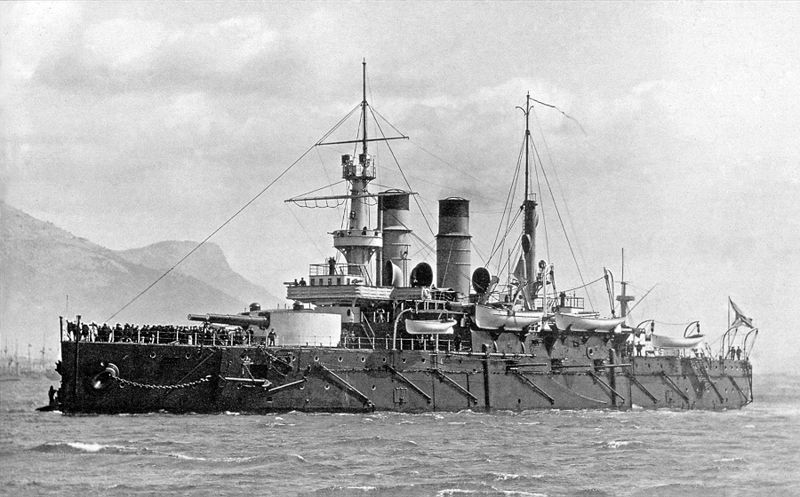

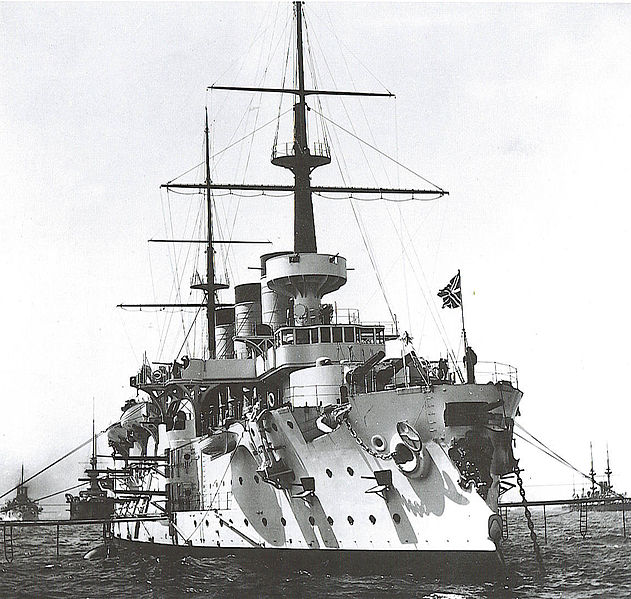

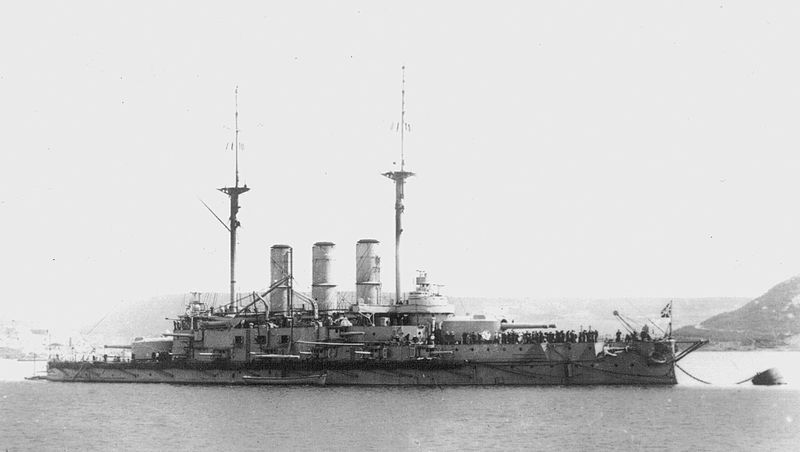

Poltava

By 1890, experience from the first of the new battleships was starting to filter back to the design offices, and was reflected in the first multi-ship class in the Baltic, the Poltavas. The design was loosely based on the American Indiana class, with turrets on the upper deck for the 8" secondary guns. While under construction, these were replaced by 6" QF guns, and the guns converted from barbettes to turrets. The guns, the new 12"/40 caliber, had a tendency to jam due to excessive recoil when fired with full charges. The ships had two different sizes of torpedo tubes, 4 15" above-water tubes and 2 18" underwater ones. Each ship of the class had a different type of armor. Petropavlovsk had plain nickel steel, Sevastopol had Harvey armor, and Poltava had Krupp armor. All of it was imported, as Russian production capacity was inadequate to meet demands.

Rostislav

Rostislav, the next Black Sea battleship, was notable for being the first battleship to burn oil. This, oddly enough, was entirely an economic decision. Oil was readily available from the Baku fields, while good coal was expensive in the Black Sea. Four of the eight boilers burned oil, while the other four burned coal. Rostislav was based on the hull of Sisoi Velikii, with 10" main guns in turrets and four twin 6" turrets. Unfortunately, the 10" guns cracked during trials, and had to have their velocity reduced, limiting range and penetration. She was so overweight that her draft when she left the yard was 22', the design draft. Unfortunately, neither weapons nor armor had been fitted yet. In 1905 continuing problems with the oil-fired boilers lead to her being converted to burn coal exclusively.

Russian Battleships during the Russo-Japanese War

During this period, Russia's eyes were turning to the Far East with the accession of Nikolai II. The increasing importance of Russian naval power meant that Russia now needed an ice-free port outside of the Black Sea, which, in practice, meant somewhere on the Pacific. Chinese fleet strength was growing, so battleships had to supplement the cruisers that made up the Russian Pacific Squadron. The other major issue was that Russian ships deployed outside of the Baltic were dependent on other nation's docking facilities for support. In 1894, war broke out between Japan and China over influence in Korea, and in the war's aftermath, Russia managed to lease Port Arthur, now known as Dalian, in China just west of Korea.

Poebda of the Peresvet class

The first battleships built specifically for the Far East were the three units of the Peresvet class. These ships could almost be seen as predecessors of the battlecruiser, intended to support the Russian armored cruisers in their campaign against British commerce in the Pacific. They were the largest Russian battleships built to date at 13,000 tons, and the fastest. Their speed of 18 kts was two knots more than had been standard, and they had great endurance as well. Their 10" guns had the same problems as those of Rostislav. The focsle was raised to improve seakeeping, and the 6" guns were laid out with double casemates and a single gun in the bow. The Peresvets also pioneered improved watertightness standards for Russian ships.

Potemkin

In the Black Sea, the Russians continued their tradition of building unique ships, with Kniaz Potemkin Tavricheskii. This ship, made famous by the mutiny in 1905 and the subsequent film, was actually one of their better designs. She was based on the hull of Tri Sviatitelia, adopted in haste when they realized they were about to run out of work at one of their shipyards. However, a focsle was added, giving vastly improved seakeeping and better habitability. The 12"/40 guns had issues, firing at half the rate of other Russian guns, which were already slow-firing by international standards. Despite this, the ship, renamed Panteleimon after the mutiny, gave good service.

Retvizan

The increasing strength of the Japanese fleet in the wake of the Sino-Japanese War worried the Russians, who thus turned abroad to increase the strength of their navy. The first result of this was the Retvizan, built by William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, one of America's premier shipbuilders. The ship was a close cousin to Potemkin, with the forecastle extended all the way to the stern, and the speed raised to 18 kts. Four 6" guns were traded for the steaming range necessary for her role on the oceans instead of the narrow waters of the Black Sea. She was the only Russian ship of the era to come in underweight, probably because the contract with Cramp prevented tinkering with the design to the usual extent.

Tsesarevich

The second Russian battleship built abroad was the Tsesarevich, built in Toulon. Unlike Retvizan, built in an American yard to a Russian design, Tsesarevich was largely French in design, with some fairly extreme tumblehome.5 She had heavier armor, including the French cellular system,6 and 12 6" guns in turrets, but considerably less endurance than her counterpart. She took a long time to build, to the point that even the Russians remarked on the sluggishness of the yard.

Slava of the Borodino class

The Borodino class was the largest-ever class of Russian battleships, with five units built for the Baltic fleet. They were based on the Tsesarevich, but adapted for Russian yards. One interesting feature was cross-flooding ducts, which connected voids on both sides of the ship, so that flooding from damage on one side was automatically compensated by flooding on the other. Their armor was slightly lighter than their French-built predecessor, but other than that, their overall performance was very similar.

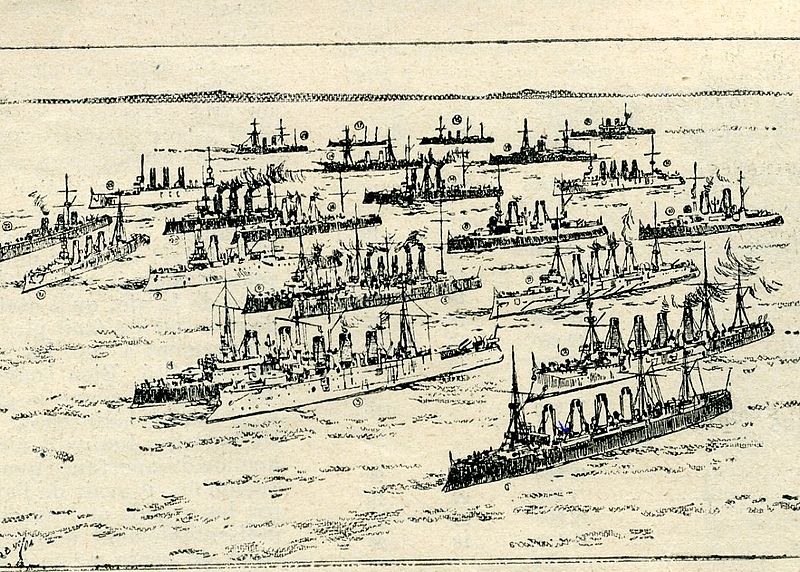

Poltava and Retvizan sunk in Port Arthur

In 1904, as the Borodinos were being built, war broke out with Japan. All of the ships mentioned in this post from the Baltic were either in the Far East when the war started, or formed part of the Pacific Squadrons sent to aid them. Unfortunately, the Russian effort met with disaster,7 but they also learned many lessons that affected future battleship designs.

Evstafi

Work in the Black Sea shipyards was about to run out in 1903, and another pair of ships were ordered, the Evstafi class. They were improved versions of the Potemkin, with four of the 6" guns replaced by 8" guns, making Russia a late adopter of the semi-dreadnought trend. The 12" gun was massively improved, dropping loading time from 90 to 40 seconds.8 As usual, the design saw a number of detail changes, although with more justification than usual thanks to the experience gained against the Japanese.

Andrei Pervozvannyi

The same program that bought the Evstafi class also ordered two extra ships of the Borodino class, but these were put on hold to be completely redesigned with the lessons of the war. What eventually emerged was the Andrei Pervozvannyi class, 3,000 tons heavier. They had all of their 6" guns removed and replaced by 14 8" guns in four twin turrets and 6 single mounts, as well as the improved 12" guns. The armor scheme was revised to improve protection against the high-explosive shells which had proved so dangerous in the Pacific, covering the entire side in armor. This meant their freeboard was low, and they thus had poor seakeeping. They also were fitted with interesting cage masts, similar to the ones used on US battleships, but thinner. These masts were not successful in service.

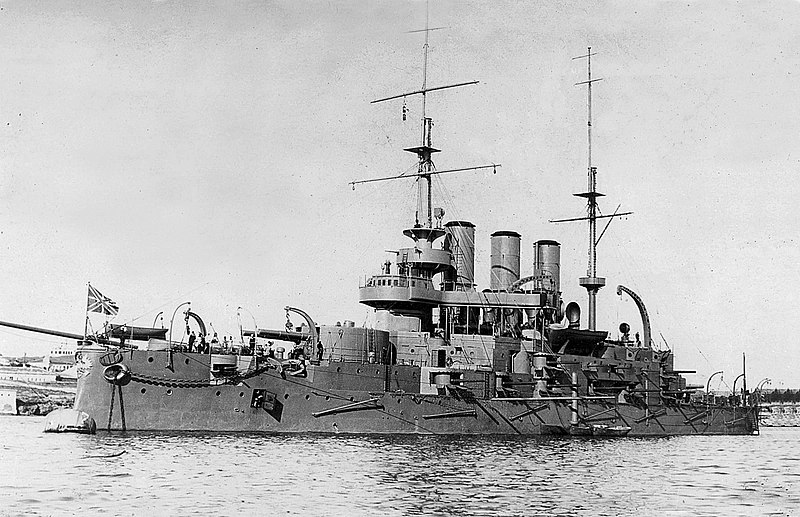

Peresvet with some of the torpedo-defense guns visible on the ship's side

There are a couple of common features of Russian design in this era that bear noting, though not in the context of any particular ship. First, most of the ships in question had thicker armor over their machinery than over their magazines. I'm not sure why this is, but similar things were done in other nations. It's possible that in the era before good explosive shells, they weren't particularly concerned with the threat of magazine explosions, and were more worried about the machinery being disabled or flooded. Second, each ship had a magazine for 40-50 mines, intended to protect a fleet anchorage. Third, Russian ships had a truly staggering number of anti-destroyer guns, usually about twice as many as contemporary British ships. McLaughlin doesn't say why this was, but I'd speculate that it was due to the Baltic and Black Seas both being smaller and more favorable to torpedo boats than the Atlantic.

All of these ships were rendered obsolete when Dreadnought entered service in 1906, and Russia quickly joined the scramble to buy all-big-gun ships. Despite this, many of their pre-dreadnoughts that didn't fight the Japanese later saw service against the Germans and Ottomans and gave good accounts of themselves.

1 This was not an idea unique to Russia. It seriously hindered British naval development until the late 1880s. ⇑

2 Oddly, this is true despite Tri Svietitelia being approximately 25% heavier. I continue to be amazed at how differently the Russians did naval architecture. ⇑

3 She was designed about 600 tons lighter than Navarin, but completed only 200 tons lighter. ⇑

4 This gave much amusement to visiting naval officers of other nations. ⇑

5 Tumblehome is when the sides of a ship slope in, making it narrower at the top than at the bottom. It makes the ship worse at recovering when it rolls, but reduces weight higher up. The French were big fans, while the British didn't like it much. ⇑

6 The area behind the belt was bounded with armored decks above and below, heavily subdivided, and filled with coal, providing excellent protection to buoyancy despite a very narrow belt. ⇑

7 I'll discuss the Russo-Japanese war in a separate series of posts at some point. ⇑

8 Contemporary British guns could fire about every 30 seconds. ⇑

Comments

I'm eagerly awaiting your posts on the Russian-Japanese war!

I have a possibly-stupid question. Were the masts of these battleships ever used for propulsion? Looking at the photos, they've got rigging on them and they certainly look like you could put a sail on profitably, but I had assumed that, once internal combustion engines were scaled up and made reliable, wind power had become entirely obsolete on warships.

@jj

It’s going to be a while. I do intend to get to it some day, but I might do the Sino-Japanese and Spanish-American wars first.

@sam

None of these ships ever carried sails. Those died out in the 1870s and 1880s. Sails take lots of experienced men to work well, and they’re kind of heavy. I'm not actually sure why these ships had yards fitted. A few years later, I'd suspect it was for radio antennas.

If your masts don't have yards, what are the men going to stand on so the ship looks smart when coming into harbour?

I thought masts were important for flying signaling flags - this being a decade or two before the radio.

@Jake

How did I forget that? That's most of it, although some of the ships have two yards on a mast, and I'm not sure what the upper one is for.

Velikh in Part 1 is the same word as Velikii in this one, and I really can't imagine anyone intentionally using Velikh as a transliteration.

Funny story about that, actually. I went back to McLaughlin, whose transliterations I've decided to follow to save myself confusion, and discovered that nobody did intentionally use Velikh. What happened was that he used Velikii, but I apparently copied it down from the chapter title, which was in all-caps. VELIKII. I have absolutely no clue about this stuff myself, so I misread the II as an H. I'll fix the mistake in Part 1.