Even after a battleship had been designed, built, launched and fitted out, it still wasn't quite ready to go into service. Anything as large and complex as a warship needs to be thoroughly wrung out before it can be considered ready to go to war.1

Iowa is inclined during her shakedown period

This was the job of sea trials, a joint effort between the builder and the navy to make sure that everything was actually working. These began with machinery trials, first simply running up the engines dockside to make sure they actually worked, and then taking the ship to sea under her own power the first time. After everyone was satisfied that the engines were working, and any deficiencies were corrected, performance trials would begin. There was always some doubt about how a new ship would perform, particularly if it was the first of the class. Several different trials would be run, most notably the 1-hour full-power trial, where the ship would run a measured mile, probably going faster than she ever would again.2 Another important trial was the 8-hour power trial, which was intended to prove that the engines could stand the strain of prolonged use at high power, if not quite so high as the 1-hour trial. Then there were economy trials, intended to give figures on fuel consumption and feedwater usage.3

Russian battleship Poltava on trials in the Baltic

But this was only the start. There were trials for seakeeping, to see how well the naval architects had done at keeping the ship dry in bad weather. Trials for maneuvering, to see how good the ship would be at dodging torpedoes or other ships, and how quickly it could accelerate or stop. Gunnery trials, to make sure of the turret machinery and fire-control systems. Particularly when a new weapon was introduced, these were watched with great care, as the potential for subtle problems to sneak into a design was much greater for rarely-used turrets than for engines, and because weapon problems could render a very expensive ship useless. All the auxiliary machinery was tested, from the electrical generation system to the firemains to the bilge pumps and refrigeration equipment. Faults would certainly be found in some, perhaps all, of these systems, and would have to be corrected before delivery. The whole process would likely take several months, with the ship in and out of the yard to fix any problems, culminating in the final set of delivery trials, also known as a shakedown cruise, to make sure that everything was in order.4

Iowa fires an AP shell during gunnery trials in 1984

Even while the ship was still fitting out, the initial crew of the ship began to form. Initially, a small core of senior officers and enlisted men were assigned to work with the shipbuilder from offices ashore. As the ship moved towards completion, their ranks grew, and they moved aboard the ship shortly before trials, providing most of the manpower for such operations. These men often took great pride in their role as "plank owners", the term for the crew that puts a new ship into commission.

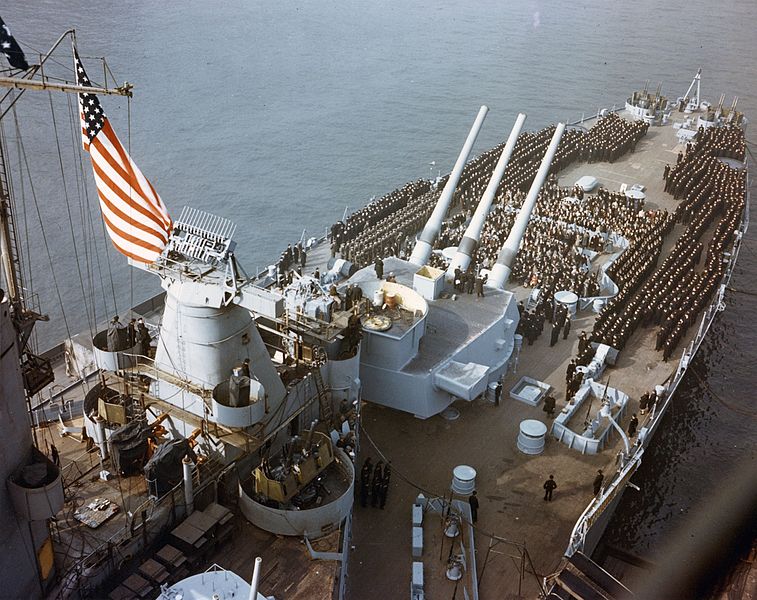

Iowa being commissioned for the first time

Finally, the big day came, the final payment, 5% or so, was made, and the title of the ship officially passed from the shipbuilder to an Admiral or other senior officer for a short period. This placed it in a sort of legal limbo, so the formal commissioning followed swiftly, as the ship's Captain took official responsibility for the ship. The officers and crew fell out on the stern of the ship, resplendent in their dress uniforms, and the Chaplain gave the invocation. The Admiral ordered the prospective commanding officer to commission the ship, and the order was passed to the crew. The national ensign, commissioning pennant and jack were hoisted, and the first watch was sent running to their stations. The ship was now officially commissioned, and short speeches from the Captain and Admiral, along with any visiting dignitaries, followed. If a presentation silver service was being given to the ship, usually by the state the ship was named after, it would be received at this point. The ceremony concluded with the benediction, and was usually followed by a reception.5

Iowa's crew running to main the rails during her third commissioning

At this point, the ship was, in theory, a warship, although in practice, it would be some time before it could actually be considered a useful one. The crew would need to get used to using the ship, and work out the practical problems could only be discovered by the end users. This was known as working up, although the amount of time it took varied dramatically depending on the situation. Prince of Wales went into action against Bismarck only four months after commissioning, with a number of representatives from the yard onboard, and had serious issues with her turrets. More common was six months or so before ships were deployed into combat, and the lead ship of a class often spent even longer wringing out bugs before she went somewhere the enemy was likely to be found.

Iowa, ready for war at last

But at long last, usually five years or so after the first designs were sketched, the new battleship was ready to go gun-to-gun with the enemy's battle fleet. But it would take a great deal of work to keep it ready, and we'll examine that in future installments.

1 This article is a mix of British and American practice, spliced together as necessary to form a coherent narrative. The overall picture should be more or less correct for all battleships for practical reasons, but details did differ between the USN and RN. ⇑

2 Battleships, unlike destroyers, weren't required by contract to make a specific speed. British destroyer contracts usually included a bonus for exceeding their contract speed, which lead to lots of shenanigans as shipbuilders tried to wring as much speed as possible out of them. In some cases, machinery was permanently damaged by being forced too much on these trials, and important things (like armament) were not installed to save weight. ⇑

3 Some battleships didn't have the full set of trials, usually because of the demands of war. The Iowas, for instance, were never run on a deepwater measured mile, because of the U-boat threat when they were first commissioned. Shallow-water tests were run, mostly in Chesapeake Bay, but ships go faster in shallow water for complicated reasons outside the scope of this post. ⇑

4 There's a lot of flexibility in the order that things are done, particularly in wartime. Based on photos, Iowa was swathed in scaffolding a week before commissioning, and looks to have done most of her shakedown/trials afterwards. ⇑

5 This paragraph is basically about USN practice. The RN takes commissioning much less seriously. This is probably because the RN, for historical reasons, takes ships out of commission when they undergo major maintenance, so the average length of a commission for a British ship is 2-3 years. The USN only takes ships out of commission when they go into reserve. ⇑

Comments

Another great post. Thanks for your work.

Do you do any youtube work? Some good stuff out there, might be a benefit to do so.

I don't do youtube work, and probably won't. I believe that youtube is strictly inferior to text for passing most information, including the kind of stuff I do. Also, it would be a lot more work, because after I finished writing, I'd have to actually make the video, which I don't really have the skills to do.

But I do appreciate the sentiment.

Drachinfel sort of has a neat niche for youtube warship content. I do agree with text being a far superior way to present more in-depth information, with footnotes and links and that sort of thing. Plus, most people can read faster than other people can talk. Keep at it.

I'm certainly not saying that there's no niche for warship content on YouTube. It's just not a niche I'm particularly interested in inhabiting. I hadn't even thought of links, but not being able to insert those smoothly would drive me bonkers.

I certainly much prefer reading text + images than watching video.

It means I can read it at work during a lunch break.

It means I can read it in bed without disturbing my wife.

It's much easier to flip back and forth, especially when dealing with links and footnotes.

What video is best at is if there is action to be described and explained. If Jorg Sprave is describing a slingshot he can show how it is used, show the construction process, show slow motion of the mechanism working.

If (when?)Bean actually gets control of a battleship and is able to take it to sea and start shelling a target then video will be a good medium to use. But until that happy day he'll be working with images and descriptions that work best in text form.

I once stated that "text is better than video" is the one unifying belief that all SSCers share, and got broad agreement on it.

I'll be way too busy to make videos if that happens. Barring that, the only thing I can do that might be meaningfully helped by video would be tour stuff aboard Iowa. And for obvious reasons, production of that would be extraordinarily slow. Also, other people have done a lot of it already. Maybe next time I'm there, I'll try shooting something in main battery fire control to see how it works. You might be able to make good warship videos with a lot of CGI, but that's way outside my skills and my budget.

I've used three videos in the entire run of Naval Gazing to date, one for Underbottom Explosions and two for Weather at Sea. In both cases, it was because I thought that video brought something to the table that I just couldn't get with text+pictures, but those cases are very rare.

(Weirdly, the underbottom explosions video is up to like 800 hits now, while the other two languish under 30. I have no explanation for this.)

Bean, one of them has an explosion in it while the others don't. Are you really so surprised? :D

It's not that I'm surprised that it's the most popular. It's that it's getting 100+ hits a month from sources that have nothing to do with this blog.