Continuing our look at the histories of interesting ships brings us to the third unit of the Iowa class, USS Missouri, BB-63. This one is going to take several parts, as Missouri had a particularly interesting career.

Missouri on trials

Missouri was ordered almost a year after Iowa, and built in the same shipyard, the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She was launched on January 29th, 1944, and commissioned on June 11th of the same year, the last of the Iowas to reach each milestone,1 and ultimately the last battleship to enter service with the US Navy.2 The ship's sponsor was Margaret Truman, daughter of a powerful senator from Missouri, whose interest in the ship would pay off handsomely.3 The launch itself didn't go that smoothly, as the bottle was prepared improperly,4 showering Margaret and one of the attending Admirals with champagne. The ship then refused to move when first released, and Margaret gave it a push, although it took another minute before she began to slide.

Margaret Truman about to christen Missouri

Missouri joined the Pacific Fleet in December of 1944 as a direct replacement for Iowa, who was heading home with a shaft casualty. She was immediately assigned to the Fast Carrier Task Force at Ulithi, and screened carriers during the first carrier raid on Tokyo since Doolittle's. Next stop was covering the invasion of Iwo Jima, where she scored her first kill on a Japanese airplane. By this stage of the war, air raids had become frequent, and Missouri's men witnessed the disastrous kamikaze hit on the aircraft carrier Franklin during another raid on Japan.

The kamikaze about to hit Missouri

As March drew to a close, the US marshaled forces to invade Okinawa, and Missouri was first tasked with participating in a diversionary bombardment, and broke in her main guns by sending 180 rounds at Japanese positions. After the troops began going ashore on April 1st, the Japanese air attacks intensified. On the 11th, it was Missouri's turn. A Zero crashed into her amidships on the starboard side. Fortunately, the bomb it was carrying didn't go off, but some of the plane's gasoline ignited. The fire was swiftly put out, but not before smoke was drawn into some of the engineering spaces, forcing the crew below into gas masks.

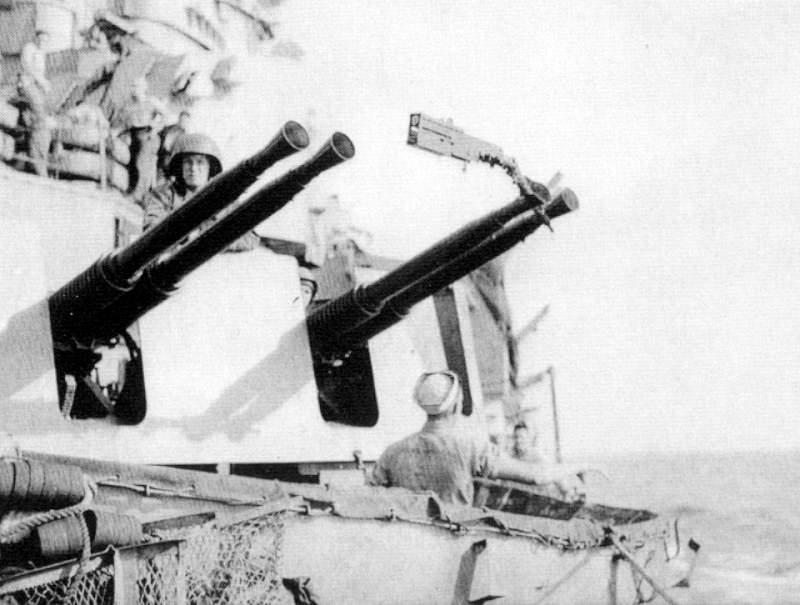

One of the kamikaze's guns, impaled on a 40mm barrel

Five days later, Missouri was subject to even more intense aerial attacks for over 12 hours. One kamikaze clipped the aircraft crane on the fantail before crashing into the water. This one did explode, wounding two sailors. By the time she returned to Ulithi, she'd claimed five kills and one probable, and fought through possibly the most intense air attacks in the entire war. There, she took aboard Admiral Halsey in preparation for his taking command of the Third Fleet. Then it was back to Okinawa, where Halsey conferred with Spruance in preparation for the change of command. Missouri was quickly swarmed by landing craft full of Marines with souvenirs of the fighting, eager to trade them for a hot meal. The officers quickly put a stop to this, and confiscated the weapons that had found their way aboard.

Missouri under kamikaze attack

As flagship, Missouri continued to support the fast carriers as they ravaged Japan. The highlight of the last months of the war was her participation alongside Iowa in the bombardments of the Japanese mainland. Then, in early August, the atomic bombs were dropped, closely followed by news of the Japanese surrender. When it became official, Halsey ordered Missouri's whistle sounded for a full minute. The whistle, which had lain dormant for months, froze open, and had to be shut off by cutting off its steam supply in the bowels of the ship.

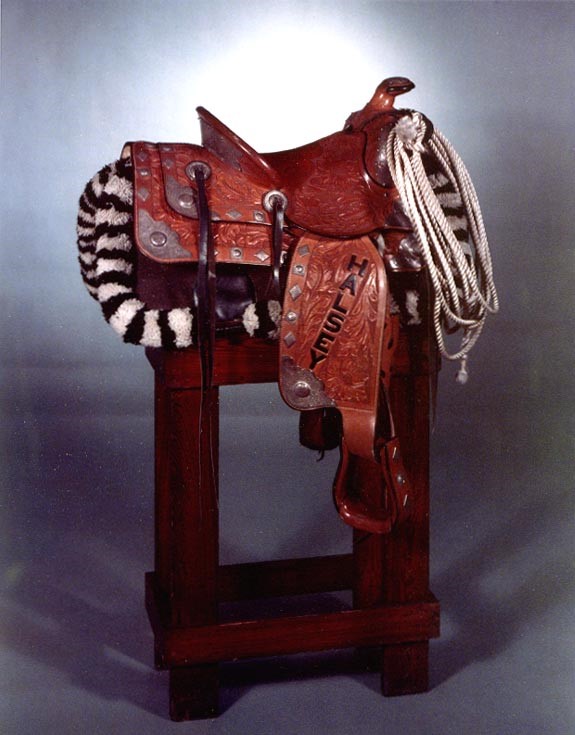

Halsey's saddle

It was decided that the surrender should take place aboard a ship in Tokyo Bay, and for security reasons, the carriers were kept outside. That left a battleship, and with now-President Truman's connection to the ship, Missouri was the obvious choice. She was duly selected, and led the fleet into Japanese waters in late August. On the 25th, she received a most unusual highline transfer, a tooled saddle from the Reno Chamber of Commerce. One of Halsey's aides had said that he would soon be "riding the Emperor's white horse", and the Reno CoC had decided to help. The saddle is now on display in the Naval Academy Museum. That museum also provided a precious artifact to Halsey, the flag flown by Matthew Perry during his opening of Japan in 1853. Halsey also received four bridles and 10 pairs of spurs from various civic groups, although I don't believe any were ever used on on the Emperor's horse.

Missouri leading Iowa into Tokyo Bay

On August 29th, Missouri led the fleet into Tokyo Bay, and her men prepared to host the end of the greatest war the world had ever seen. A set of commemorative cards were printed to be issued to the men onboard during the ceremony, and then the dies were destroyed. On the morning of the 2nd, it was discovered that the mahogany table the British had provided was too small for both sets of surrender documents, so one of the tables from the general mess was substituted, with a green baize cloth to hide it. 170 reporters came aboard to document the occasion, and at 8, an hour before the ceremony, Admiral Nimitz came aboard. 45 minutes later, General MacArthur came aboard, and two five-star flags flew from Missouri's yards. It is commonly reported that Missouri flew a flag that had been above the Capitol or the White House when Pearl Harbor was attacked, but Captain Murray of the Missouri said that it was instead a standard-issue flag. Murray also ordered a position taken from six landmarks, and then had the ship's gyrocompasses cut off to prevent anyone else claiming they had taken a more accurate fix on the location of the surrender.

The Japanese surrender delegation

At 8:55, the Japanese delegation came aboard, lead by Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu. The eight sideboys who greeted them had been specially chosen to be over 6' tall, and they towered over the Japanese. They were led up to the 01 level, just outside the captain's in-port cabin, where the table and the Allied delegation waited. Missouri's upperworks were crammed with men, all struggling for a good view of the historic moment. Finally, at 9:04 AM, on September 2nd, 1945, Shigemitsu signed the document, followed by Yoshijirō Umezu of the Imperial General Staff. Four minutes later, Douglas MacArthur signed for the Allies, flanked by Johnathan Wainwright and Arthur Percival, captured in the Philippines and Singapore respectively. Next was Chester Nimitz for the US, followed by representatives of China, the UK, the Soviets, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand.

MacArthur accepting the Japanese surrender

The ceremony wasn't entirely without a lighter side. Several of the photographers assigned attempted to get better vantage points, and were hauled bodily back to their positions by the ship's crew. As the final signatures were put on the documents, 450 airplanes from the carriers stationed offshore flew overhead, followed by B-29s from the Marianas. It was a fitting end, with the naval and air power that had brought down the Empire of Japan on full display.

The planes of the Pacific Fleet fly over Missouri

Missouri swiftly returned home after the end of the war, and was reunited with her sponsor and her sponsor's father on Navy Day in New York, when the Trumans came aboard before inspecting the fleet from the destroyer Renshaw. The next day, she moored in Manhattan, and during the 10 days she was alongside three-quarters of a million people visited, many of whom attempted to steal everything not nailed down. She then entered New York Navy Yard for a well-deserved overhaul.

Truman inspecting the fleet from Renshaw, with Missouri in the background

In 1946, the Turkish ambassador, Munir Ertegun, died, and Truman sent Missouri to return his body. In Istanbul, she met up with the last remnant of the High Seas Fleet, the former German battlecruiser Yavuz, then made port visits throughout the Mediterranean, serving as an excellent ambassador in a still-uncertain postwar Europe.

Missouri and Yavuz

A year later, Missouri was sent on another diplomatic mission, this time to Brazil. President Truman and his family had flown down to a conference in Rio de Janeiro, and Missouri was to return him to the US. While there, she met the eponymous ship, another relic of the early dreadnoughts, and hosted many visitors. Then it was time to return stateside. Truman was popular with the crew, leading calisthenics on deck and being willing to talk with them, while Margaret ate in the general mess and teased the captain that it was her ship, not his, a joke he didn't appreciate. However, the highlight was the line-crossing ceremony. While the crew had crossed the line going south, the ceremony was delayed so the Presidential party could participate. The normal pollywogs5 were charged with the usual array of bizarre crimes, and subjected to the sometimes-brutal punishments from the shellbacks.6 Truman himself was charged with using a "despicable and unnatural means of travel" (the airplane he'd flown to Brazil) and sentenced to provide King Neptune's court with cigars and autographs, while his wife and daughter got off essentially scot-free.

President Truman faces the court

Missouri spent the next two years as a training ship, taking midshipmen on cruises to the Caribbean or to Europe. When Iowa was decommissioned in March of 1949, Missouri was the only battleship remaining in service, and Truman explicitly promised that as long as he was President, she would not be retired. She was the perfect vessel for training future officers, with lots of room and only a skeleton crew. But the beginning of 1950 brought disaster to the ship, which we'll cover next time.

1 While Wisconsin has a higher hull number, she was about two months ahead of Missouri during construction. ⇑

2 Two more ships, Illinois and Kentucky, were laid down, but never completed. ⇑

3 It's traditional to have a female sponsor responsible for christening the ship on launching, and who often then serves as an informal patron to the ship. This honor was usually offered to the Governor's wife or daughter, but the Governor of Missouri at the time was a Republican, while Truman was the head of an eponymous committee charged with fighting waste and inefficiency in the war effort, so the Navy Department took the chance to gain his favor. ⇑

4 Champagne bottles for ship christenings are traditionally scored so they break properly, but the Treasury Department screwed up on Missouri's. ⇑

5 Those who had not crossed the equator before. ⇑

6 Sailors who had previously been across the equator, and who ran the ceremony. ⇑

Comments

Very random aside: I think the 48 star flag still looks the best.

What's off the port bow in the first picture? Some kind of barge?

A barge of some sort. I don't remember what kind.

Well done as always, Bean! For April 1st next year you should do a full post on these various nautical traditions and cerimonies.

The title is obvious and will be left as an exercise to the reader.

I have line-crossing ceremonies, and broader traditions of the sea, very much on my list. I don't plan to run it April 1st, which is a slot I'll have to reserve for something more in the line of what I did this year.

I'd be curious to hear more about why he did this.

Basically, he wanted to be sure that his official position for the surrender wouldn't be challenged by anyone else.