After the overthrow of the Tsarist regime, the energy of the new Soviet military was primarily concentrated on the army, and with good reason. The USSR faced threats on every land border, while naval threats were fairly minimal. The Soviet Navy soldiered on with a few ships from the days of the Tsars, most prominently the remaining battleships of the Gangut class. But this would all change in the 1930s.

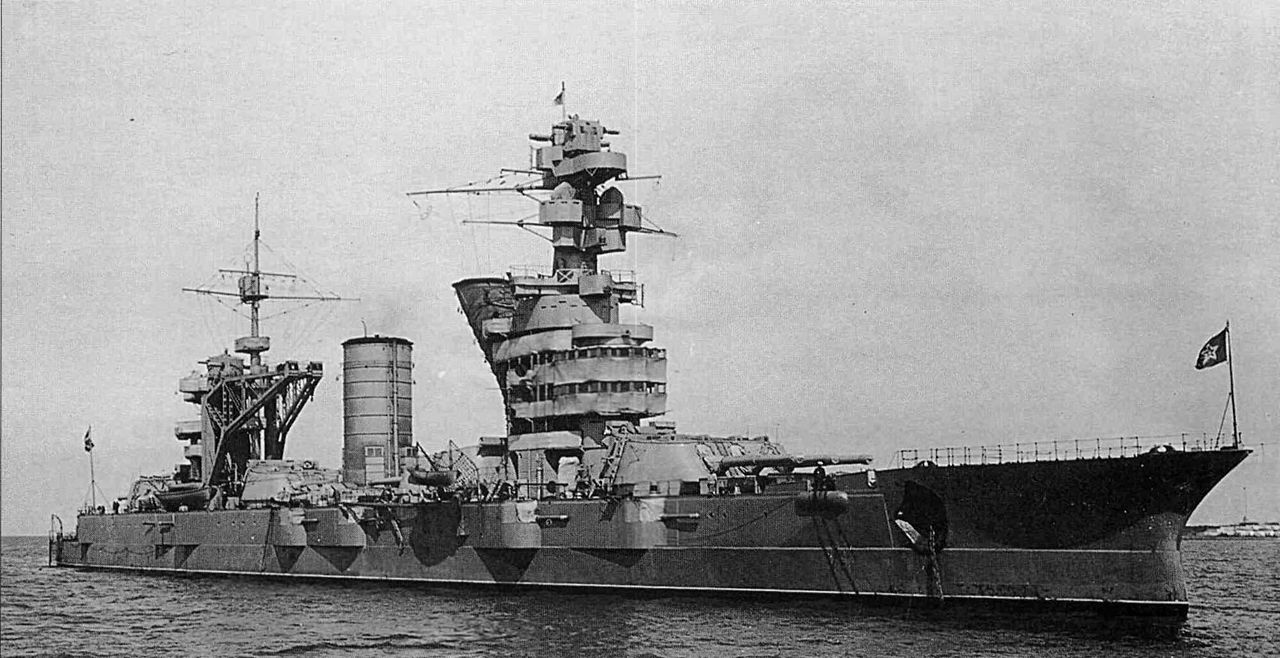

Oktyabrskaya Revolyutsiya, formerly Gangut, in 1934

Joseph Stalin began talking about a new navy as early as 1931, apparently seeing a great oceanic fleet as necessary to the power and prestige of the Soviet state, a deterrent against the enemies he was sure were plotting against him.1 However, nothing came of this discussion until 1935, when serious work on designs began, under the designation "large armored artillery ships". This was prompted by a worsening international situation, particularly the rise of Germany under Hitler. In fact, the first batch of design studies were for ships of 26,000 tons, the same size that had recently been announced for the Scharnhorst class. The plan actually approved in June 1936 showed 8 35,000 ton ships and no fewer than 16 26,000 ton vessels, a battleship construction program unmatched by even the major naval powers.

Of course, it wouldn't be Russia if this plan went smoothly. The Navy was strongly in favor of the biggest possible ship, drawing up plans for vessels in the region of 55,000 tons. However, Stalin chose to sign a naval agreement with the British in mid-1937, committing the USSR to follow the terms of the Second London Treaty, with an escalator clause to deal with Japan. The plan was torn up a few months later, and a new one was drafted, with 6 large and 12 small battleships, in roughly the same size categories as under the previous plan, although the addition of lighter units meant that the total tonnage had risen 50%.2

Dunkerque

The small battleship, known as Design B, went through a number of odd twists and turns during its ultimately unsuccessful gestation. The initial concept was a ship designed for the Baltic and Black Seas, and aimed at overmatching the treaty cruisers and "pocket battleships" the Soviets believed were likely to be found there.3 The design quickly escalated from 26,000 tons and 12" guns, falling into the same broad category as the contemporary Scharnhorst and Dunkerque classes, to 35,000 tons and 16" guns, a full match for the treaty battleships being designed in the US and Britain. Despite this, and a 14" belt, the ship was still supposed to make 36 kts, a figure that even Soviet designers soon realized was impractical. The armament of most of these studies was all-forward, as in the Nelsons, and the Italian Puligese torpedo defense system was used.4

All of this was done before Anglo-Soviet naval negotiations began in mid-1936, which would probably bring the Soviets into the treaty regime, limiting them to 35,000 ton ships. The obvious solution would have been to use the existing Design B as the basis for the new large battleship. Instead, both existing designs5 were torn up, and Design B reverted to the 26,000 ton cruiser-killer while Design A started from scratch at 35,000 tons. In November 1936, both Soviet design bureaus presented their proposals for evaluation "at a high level", which presumably meant for Stalin, and TsKB-1 won for the small battleship even as their rivals at KB-4 were awarded the larger vessel. Four ships were immediately ordered, to be laid down a year later, even though detail design had not yet begun. The design, now grown to 30,900 tons, had 9 12" guns, 12 130mm secondaries, 8 100mm AA guns, and an 8" belt, along with a speed of 35 kts. Of course, as you've probably expected, the design was faced with massive changes in early 1937, including a shift from four to three shafts, to standardize with Battleship A, and an extra 4" of belt armor.

Scharnhorst

All of this had gone on against the background of the Great Purge, although the Navy had been spared until mid-1937, when Design B was declared "wrecked", implying intentional sabotage, and the whole thing was quickly and unceremoniously cancelled. However, the niche of something bigger than a cruiser, and smaller than Battleship A, which continued to grow out of control, ultimately lead to the Kronshtadt class, which greatly resembled the abortive Design B.

In 1938, an extra provision was signed to raise the limit for the Soviets to 45,000 tons, in accordance with the escalator clause already invoked by the treaty powers. At this point, things got really chaotic, as the Purge resulted in constant turnover at the top of all of the various parties involved.6 The major players were the naval staff, the shipbuilding administration, and the two major design bureaus, none of whom could quite agree on anything. Any decisions or agreements they made had to be signed off by Stalin himself, and it was fairly common for him to decide that he had a better grasp of naval warfare than the experts and throw out months of work on a whim. As it was, the Soviet Union never completed a single battleship, and the fact that they got as far as they did is rather remarkable. We'll look at those ships next time.

1 This makes him the only major world leader to display less understanding of the use and purposes of sea power than Wilhelm II, which is a really high bar to clear. ⇑

2 This plan initially included a few 10,000 ton carriers. Stalin, who undervalued carriers, personally deleted them. ⇑

3 Stalin had set up separate Northern and Pacific fleets, which had unrestricted access to the ocean and their own building facilities. I suspect that cost kept the Tsar's navy from doing the same. ⇑

4 The Soviets attempted to get foreign help with their naval construction program from a number of nations, but only the Italians were particularly forthcoming. I'll go into this in more detail later on. ⇑

5 The travails of Design A will be covered elsehwere, as they ultimately led to actual steel on the slipway, if not in the open sea. ⇑

6 It wasn't all bad news for the Soviet Navy, though. In December 1937, it was moved out from under the Red Army and made a separate service, giving it an independent voice at the highest levels of government. ⇑

Comments

Was Stalin wrong to think that carriers wouldn't meet the USSR's strategic requirements? Carriers would be nearly useless in the Baltic and Black Seas where land based aircraft have full coverage. Putting a few at Vladivostok would be suicide if they dared to challenge the Kido Butai.

Perhaps the Northern Fleet might have a nice niche for carriers as lend lease convoy escorts, but anticipating vast support from the West in the 1930s from Moscow's perspective is too 20/20 hindsight for me.

Stalin was trying to build a seagoing fleet. Shore-based aviation is fine when you're working in narrow seas, but if you're building ships for the Baltic and Black Seas, battleships are probably a poor choice anyway. But if you're in the open ocean, you really need air cover.

So I have to ask - if someone really wanted to build a Soviet navy circa 1935, what the hell would you try to build?

I'm tempted to say "U-boats and let all that filthy capitalist trade slip beneath the waves", but I'm not sure if there's a better role for their hypothetical fleet.

For blue-water forces, I don't see much need for anything beyond a lot of submarines and some cruisers for showing the flag and maybe a bit of light commerce raiding. Coastal forces are a different matter. There, you're going to want destroyers and torpedo boats, but you can afford to operate rather differently because you're not going out in blue water.

Submarines are fairly much the default choice in 1935 for a major, but not super, power that itself doesn't have much seaborn trade.

In 1935 the USSR was faced off against Germany, which was vulnerable to cutting off sea trade. And Japan, which was extremely vulnerable (both examples being proven within a handful of years).

I don't think large submarine fleets make sense for the USSR until the advent of truly long range subs in the early Cold War for attacking NATO REFORGER convoys after slipping past the GIUK gap. With the very limited submarines of the 1930s, you simply don't have the range to operate far out into the Atlantic from bases in Arctic Russia.

The Black/Baltic seas aren't exactly ideal terrain for submarines either due to the availability of land based air coverage and their natural shallow depths compared to the Atlantic.

I think the Soviets started WW2 with the world's largest sub fleet and some fairly high quality boats in the Shchuka and Srednyaya classes, but in terms of tonnage sunk compared to number of boats lost, they were drastically outperformed by the Kriegsmarine and USN. Besides, Axis Europe was far less dependent on imports from Sweden than say the UK was dependent on imports for everything.

Japan was of course immensely vulnerable to interdiction of its merchant marine, but if the Soviets dared to fight Japan without the support of the Western Allies already knocking out most of the Japanese surface fleet, I suspect their submarine bases at Vladivostok would not have lasted very long against vastly superior and more numerous Japanese carrier and battleline assets.

Having much of a navy at all beyond limited coastal defense tools before 1960 or so just seems like a suboptimal use of steel, engineering talent, and industrial capacity for the USSR, especially when there's such a desperate need for AFVs and aviation.

I dunno, given the USSR's ideological commitment to global influence, it seems pretty clear they'd want a blue-water navy in the long term. So unless it was obvious they'd be in an existential war soon, it wasn't such a bad choice to get one started.

@Chris

I'm not sure the range limits were inherent to submarines at the time. The K-class would have been able to operate in the Atlantic and it's a 1930s design. I'm not advocating for a huge navy, but even a few submarines can do the "fleet in being" thing and tie up a bunch of men and a lot of steel in safeguarding trade. And given how vulnerable some possible opponents are to trade disruption, not looking at submarines as a counter is rather foolish. Remember, they don't know who they'd have to fight.